16 Liver disease

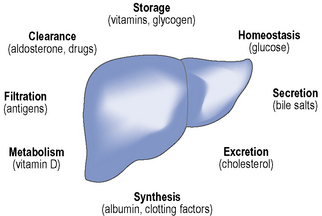

The liver weighs up to 1500 g in adults and as such is one of the largest organs in the body. The main functions of the liver include protein synthesis, storage and metabolism of fats and carbohydrates, detoxification of drugs and other toxins, excretion of bilirubin and metabolism of hormones, as summarised in Fig. 16.1. The liver has considerable reserve capacity reflected in its ability to function normally despite surgical removal of 70–80% of the organ or the presence of significant disease. It is noted for its capacity to regenerate rapidly. However, once it has been critically damaged multiple complications develop involving many body systems. The distinction between acute and chronic liver disease is conventionally based on whether the history is less or greater than 6 months, respectively.

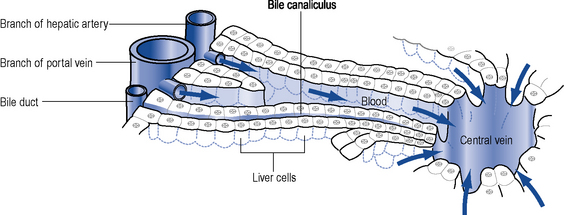

The hepatocyte is the functioning unit of the liver. Heptocytes are arranged in lobules and within a lobule hepatocytes perform different functions depending on how close they are to the portal tract. The portal tract is the ‘service network’ of the liver and contains an artery and a portal vein delivering blood to the liver and bile duct which forms part of the biliary drainage system (Fig. 16.2). The blood supply to the liver is 30% arterial and the remainder is from the portal system which drains most of the abdominal viscera. Blood passes from the portal tract through sinusoids that facilitate exposure to the hepatocytes before the blood is drained away by the hepatic venules and veins. There are a number of other cell populations in the liver, but two of the most important are Kuppfer cells, fixed monocytes that phagocytose bacteria and particulate matter, and stellate cells responsible for the fibrotic reaction that ultimately leads to cirrhosis.

Chronic liver disease

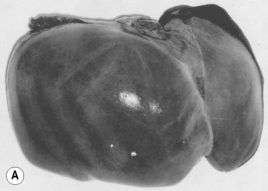

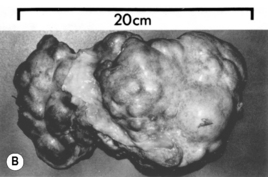

Chronic liver disease occurs when permanent structural changes within the liver develop secondary to long-standing cell damage, with the consequent loss of normal liver architecture. In many cases, this progresses to cirrhosis, where fibrous scars divide the liver cells into areas of regenerative tissue called nodules (Fig. 16.3). Conventional wisdom is that this process is irreversible, but therapeutic intervention in hepatitis B and haemochromatosis has now repeatedly documented cases of reversal of cirrhosis. Once chronic liver disease progresses, patients are at risk of developing liver failure, portal hypertension or hepatocellular carcinoma. Cirrhosis is a sequel of chronic liver disease of any aetiology and it develops over very variable time periods from 5 to 20 or more years.

Causes of liver disease

Immune disorders

Metabolic and genetic disorders

There are various inherited metabolic disorders that can affect the functioning of the liver.

Clinical manifestations

Signs of liver disease

Cutaneous signs

Hyperpigmentation is common in chronic liver disease and results from increased deposition of melanin. It is particularly associated with PBC and haemachromatosis. Scratch marks on the skin suggest pruritus which is a common feature of cholestatic liver disease. Vascular ‘spiders’ referred to as spider naevi are small vascular malformations in the skin and are found in the drainage area of the superior vena cava, commonly seen on the face, neck, hands and arms. Examination of the limbs can reveal several signs, none of which are specific to liver disease. Palmar erythema, a mottled reddening of the palms of the hands, can be associated with both acute and chronic liver disease. Dupuytren’s contracture, thickening and shortening of the palmar fascia of the hands causing flexion deformities of the fingers, was traditionally associated with alcoholic cirrhosis. It is now considered to be multifactorial in origin and not to reflect primary liver disease. Nail changes, highly polished nails or white nails (leukonychia) can be seen in up to 80% of patients with chronic liver disease. Leukonychia is a consequence of low serum albumin. Finger clubbing is most commonly seen in hypoxaemia related to hepato-pulmonary syndrome, but is also a feature of chronic liver disease (Table 16.1)

Table 16.1 Physical signs of chronic liver disease

| Common findings | End-stage findings |

|---|---|

| Jaundice | Ascites |

| Gynaecomastia & loss of body hair | Dilated abdominal blood vessels |

| Hand changes: | Fetor hepaticus |

| Palmar erythema | Hepatic flap |

| Clubbing | Neurological changes: |

| Dupuytren’s contracture | Hepatic encephalopathy |

| Leuconychia | Disorientation |

| Liver mass reduced or increased | Changes in consciousness |

| Parotid enlargement | Peripheral oedema |

| Scratch marks on skin | Pigmented skin |

| Purpura | Muscle wasting |

| Spider naevi | |

| Splenomegaly | |

| Testicular atrophy | |

| Xanthelasma | |

| Hair loss |

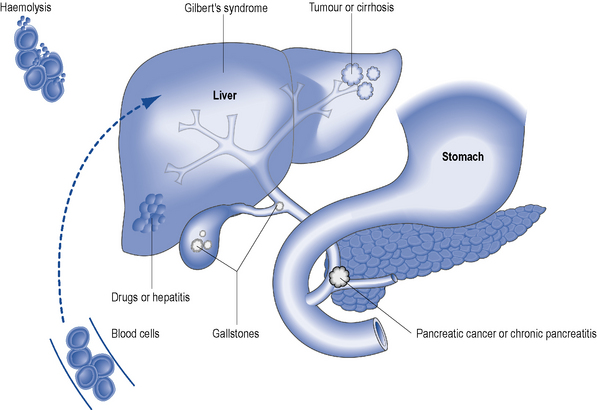

Jaundice

Jaundice is the physical sign regarded as synonymous with liver disease and is most easily detected in the sclerae. It reflects impaired liver cell function (hepatocellular pathology) or it can be cholestatic (biliary) in origin. Hepatocellular jaundice is commonly seen in acute liver disease, but may be absent in chronic disease until the terminal stages of cirrhosis are reached. The causes of jaundice are shown in Fig. 16.4.