17 The liver is the second most common organ injured in abdominal trauma. Blunt liver trauma, for example following road traffic accidents, is more common than penetrating trauma such as stab or gunshot injuries. The mortality is much higher for blunt liver trauma and it increases even more if associated with other visceral injuries. Types of injuries include laceration, contusion, haematoma, vascular injury, bile duct and gallbladder injury. Over the last two decades there has been a paradigm shift in liver trauma management from compulsory operative treatment to non-operative management.1–4 1. The patient will frequently present in a shocked state: the first priority is to maintain airway, breathing and circulation (ABC), following the principles of advanced trauma life support (ATLS). After ensuring normal cardiorespiratory function, carry out a secondary survey, examining the head, spine, chest and limbs as well as the abdomen. If the external injuries do not explain the degree of shock, assume there is internal bleeding. Stop external haemorrhage by direct pressure, splint any broken limbs, protect a fractured spine, treat a crushed chest by mechanical ventilation and assess any head injury. Now direct your attention to the internal bleeding. 2. Focused assessment sonography in trauma (FAST) is very valuable in diagnosing free intra-peritoneal fluid when performed by trained staff but is not reliable in diagnosing parenchymal injury. An emergency laparotomy is mandatory in the presence of free intra-peritoneal fluid on FAST in a haemodynamically unstable patient. However, if the patient is haemodynamically stable then obtain an urgent contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan to diagnose and grade parenchymal injury. The four quadrant abdominal tap was superseded by diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL). However, DPL is often oversensitive and nowadays is performed less frequently due to increased use of FAST and CT. Very few surgeons in the UK now have experience in performing DPL. 3. If you remain in doubt and the patient fails to respond to resuscitation, consider performing an emergency laparotomy. 4. Penetrating injuries and gunshot wounds are treated by laparotomy. Treat conservatively only selected patients with stab injury who are haemodynamically stable and in whom there is no evidence of hollow viscus perforation. 5. Treat conservatively those patients with blunt trauma who are haemodynamically stable, even if there is demonstrable liver injury on CT or ultrasound scan. Monitor the patient with repeated clinical assessment and scans. If the patient becomes haemodynamically unstable or develops signs of peritonitis, proceed to a laparotomy. 6. Interventional radiology is now an important part of liver trauma management. Angiography and hepatic artery embolization is safe and effective in controlling hepatic arterial bleeding. If the patient is haemodynamically stable, consider angiography and embolization if there is extravasation of contrast on CT. This will decrease the number of blood transfusions and may avoid a laparotomy. 1. Have you booked an intensive care unit bed if needed postoperatively? 2. You are about to embark on a major surgical procedure, carrying a high mortality rate. As far as possible, ensure you have an experienced anaesthetist, competent assistant and experienced scrub nurse. Ensure vascular clamps and sutures are readily available. 3. Maintain good communication with your anaesthetist and scrub team. There is potential for sudden, life-threatening haemorrhage during the procedure. Good team work is essential for achieving a successful outcome. 4. Check the clotting. If coagulopathy is present give fresh-frozen plasma (FFP), platelets and cryoprecipitate as necessary. Watch for the deadly triad of coagulopathy, hypothermia and acidosis. If this is present then surgical control of the bleeding is unlikely to be successful. 5. Pass a bladder catheter. It is essential to monitor urine output and ensure adequate fluid volume replacement during major liver surgery to avoid acute renal failure. 6. Your anaesthetist will place a central venous line, wide-bore peripheral venous lines and, ideally, an arterial catheter to allow constant measurement of arterial pressure. A warming blanket is used to prevent hypothermia. 7. Ensure there are at least six units of blood available, together with FFP and platelets to replace lost clotting products. 1. If you suspect the diagnosis preoperatively, use a transverse incision in the right upper quadrant, extending from a point 2 cm above the umbilicus to a point on the midaxillary line midway between the subcostal margin and iliac crest, with a vertical midline extension to the xiphoid. If necessary extend the incision across the midline transversely in the left upper quadrant. If you need to gain access above the liver, create a second incision in the tenth rib bed from the anterior axillary line to join the original subcostal incision at right angles. This allows you to open the chest, divide the costal margin and so gain control of the inferior vena cava (IVC) above the diaphragm. 2. If you discover the rupture at diagnostic laparotomy through a midline incision, create a transverse lateral extension to the right (as described above) to gain access and assess the need for further extensions. 3. If you discover the rupture through a lower abdominal incision, close it and re-explore the abdomen through an appropriate incision. 4. Use a self-retaining retractor that can be fixed to the operating table and provides forcible upward retraction of the costal margins, such as Thompson’s retractor (Thompson Surgical Instruments Inc.). It crucially reduces the need for manual assistance, greatly improves access and usually eliminates the need for thoracic extension of the incision. 1. There is usually a great deal of blood clot in the peritoneal cavity and probably some fresh bleeding. Remove clot with your hands and a sucker. 2. Look systematically for damage to the liver, spleen, the gut from oesophagus to rectum, pancreas, anterior and posterior abdominal wall and the diaphragm. If necessary, pack the abdominal cavity with sterile packs, removing them serially, inspecting each of the four quadrants in succession. 1. If there is obvious damage to, and haemorrhage from, another intra-abdominal viscus such as the spleen, and that is the primary source of bleeding, surround the damaged area of the liver with large sterile packs and have an assistant apply gentle pressure to control the bleeding. Attend to the lesion in the other organ first, and then turn your attention to the liver. 2. Inspection and palpation of the liver surface will allow you to estimate the extent of the parenchymal injury. Place packs over the superior and inferior surfaces of the liver to compress the laceration or contusion. Remove blood and blood clots to gain adequate exposure of the bleeding area of the liver. The initial packing with compression of the liver parenchyma will control much of the active bleeding. If the patient has coagulopathy, wait with the packs in place until sufficient FFP, platelets or cryoprecipitate have been transfused. Most patients do not require major surgical procedures: attempt only the minimum surgery necessary to control haemorrhage. 3. If initial packing does not control the haemorrhage then perform inflow occlusion (Pringle manoeuvre) by inserting a finger through the opening into the lesser sac behind the hepatic hilar structures and apply a Satinsky or other vascular clamp across them. If you do not have vascular clamps available, carefully apply a non-crushing intestinal clamp. This manoeuvre stops bleeding from branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein. 4. If bleeding persists despite the Pringle manoeuvre, then the bleeding is from the hepatic veins or the inferior vena cava, or the patient may have an aberrant arterial supply such as an accessory left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery, or an aberrant right hepatic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery. 5. Avoid rough handling of sites of injury that are not bleeding at the time of exploration. If the patient is hypotensive there is risk of reactionary haemorrhage when the blood pressure subsequently rises. 6. Explore the liver injury locally and remove any devascularized tissue. If the laceration continues to bleed and extends deeply into the liver parenchyma, gently explore the depth of the wound but avoid creating further damage. This procedure is very important in contusion injuries where major branches of the liver vessels may be ruptured, producing large areas of devascularized tissue. Do not be tempted to explore tears that are not bleeding, since you only encourage further bleeding. 7. Identify bleeding points and ligate them with fine synthetic absorbable material such as polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) or polydioxane sulphate (PDS) or use titanium Ligaclips. Suture-ligate larger vessels with PDS or Vicryl. 8. If there is vascular oozing from a large raw area of liver, cover it with one layer of absorbable haemostatic gauze (Surgicel) and apply a pack. Fibrin sealants such as Tisseel or Tachosil (Baxter) may help in stopping the ooze from a raw surface. Avoid using deep mattress sutures to control such bleeding, since they may produce areas of devascularization, which predisposes to subsequent infection. 9. Although a normal liver can tolerate normothermic ischaemia for up to 1 hour, after clamping the liver hilar vessels it is advisable to release the clamp for 10 minutes every 15 minutes, timed by the clock. 10. Before releasing any vascular clamps after prolonged clamping, warn the anaesthetist so that they may take precautionary measures against the effects of massive acidosis and potassium release, which can cause cardiac arrest. 11. Injuries involving the major hepatic veins close to the suprahepatic inferior vena cava or injuries to the retrohepatic inferior vena cava are very difficult to treat and even in experienced hands they are associated with high mortality. Bleeding from such injuries is not controlled by clamping the liver hilum. Attempt to mobilize the inferior vena cava above and below the liver. Complete mobilization of the right lobe of liver is required to expose the retrohepatic vena cava: identify the caval tear and suture it. Clamping the vena cava above and below the liver in addition to clamping the liver hilum will achieve total vascular isolation of the liver, but do not attempt this unless you are very experienced. Veno-venous bypass can be used to shunt blood from the femoral vein to the internal jugular vein to maintain venous return to the heart when total vascular isolation is attempted. However, expertise in veno-venous bypass is generally available only in specialist transplant units. 12. Perihepatic packing. If you cannot achieve control using the described techniques, do not attempt a major resection as an emergency procedure without the assistance of an experienced hepatic surgeon. This is rarely necessary in an emergency and has a high mortality rate. It has been shown in several studies that control is better achieved by packing around the liver with gauze rolls. Do not insert gauze into the depths of a liver laceration. Gently place the packs above, behind and below the liver to compress the bleeding areas (Fig. 17.1). 13. Having gained control with perihepatic packing, close the abdomen. Carry out a contrast-enhanced CT scan and if necessary, a hepatic angiogram. You may then choose to either re-explore in 48–72 hours to remove the packs and re-assess, or transfer the patient to a specialist liver surgery unit. 14. If you encounter torrential bleeding from the liver during the laparotomy, consider autotransfusion using a cell saver system, if available. This will allow you to keep pace with the blood loss whilst attempting to control the haemorrhage. 15. Is there damage to the extrahepatic biliary tree? Attempt reconstruction by anastomosing cut ends of the bile duct end-to-end over a T-tube splint inserted through healthy bile duct. Use fine, interrupted absorbable sutures such as 4/0 Vicryl or PDS. If the damage to the duct is excessive, identify the most distal section of duct which is undamaged below the liver and divide it there. Suture-ligate the distal stump of the bile duct. Anastomose the proximal end of the bile duct to the side of a loop of jejunum, preferably a Roux-en-Y loop, using interrupted sutures of fine Vicryl or PDS in a single-layer anastomosis. 16. If the patient is very ill and unstable, there is no urgency in carrying out a biliary anastomosis. Leave a tube drain through the abdominal wall down to the site of biliary leak; the repair can be carried out by an expert at a later date. 1. When you have gained control of the bleeding from the liver, carry out a full, careful and gentle exploration for other intra-peritoneal injuries if you have not done so already. Examine the entire gut from the oesophagus to rectum, paying special attention to the retroperitoneal duodenum, the pancreas and the spleen. 2. When you are certain that haemorrhage is controlled and that other lesions have been appropriately dealt with, inspect the liver once more, unless you needed to pack it to control haemorrhage. If there are devascularized areas, remove them to prevent infection. 1. Before you close, mop the peritoneal cavity dry with surgical swabs, or carry out a gentle lavage with warm normal saline and then suck out all the fluid. 2. Close the abdomen using a standard mass technique. 3. If you have operated on any part of the biliary tract insert a drain, preferably with a closed system. If there is liver parenchymal damage only, then a drain is probably unnecessary in the absence of an obvious biliary leak. 1. Admit the patient to an intensive care unit or high-dependency nursing area. 2. If further operation is required, for example because packs were inserted to control haemorrhage, arrange transfer to a specialist unit if possible. Packs increase the risk of sepsis, therefore give antibiotics whilst packs are in place. 3. Mechanically ventilate the patient electively and maintain the blood gases within normal range until the patient is haemodynamically stable, other injuries have been treated and the core temperature has returned to normal. Correct any remaining electrolyte imbalance. Measure blood sugar hourly and treat any abnormality immediately. 4. Evaluate biochemical liver function daily. 5. Maintain intravascular volume and normal clotting. Transfuse with blood and FFP as required. 6. Maintain urine flow. If it falls below 30 ml/hour, first check that the circulating blood volume is adequate, with normal blood pressure and central venous pressure. If you are in any doubt about this, give a ‘fluid challenge’ of 250 ml of colloid intravenously. If this fails to stimulate urine flow despite an adequate blood pressure and normal central venous pressure, consider a low-dose dopamine infusion. If this fails to improve urine flow give 40 mg of furosemide (frusemide) intravenously and seek the advice of a renal physician. 7. Give broad-spectrum antibiotics such as a combination of cefuroxime and metronidazole. 8. If gastrointestinal activity does not return within 2–3 days, institute intravenous nutrition. 9. Sudden collapse suggests that the patient has developed further internal bleeding or septicaemia. If this is associated with abdominal swelling, resuscitate with intravenous blood or colloid, and FFP if the clotting screen is abnormal. Order a contrast-enhanced CT scan and return the patient to the operating room if haemorrhage is confirmed. 10. If you suspect septicaemia then order investigations to determine the source. Culture blood, urine and any leaking body fluid; order a chest X-ray and carry out an ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen to look for an abscess. Give appropriate antibiotics. Drain an intra-peritoneal abscess either by a further operation or by ultrasound-guided needle aspiration. If the patient is very shocked and the diagnosis uncertain, it is safer to re-explore the abdomen than to wait. Intra-abdominal sepsis is very common following liver trauma and devascularized areas of the liver may become necrotic and infected. 1. If arterial injury is suspected due to extravasation of contrast on CT or signs of active haemorrhage in the absence of another source of bleeding, obtain a hepatic arteriogram before re-exploration to allow preoperative embolization and to fully assess any vascular damage: this will allow you to prepare for appropriate surgical management and, if necessary, obtain expert help. 2. Ensure that the patient is stable and correct biochemical and haematological abnormalities. Discuss any clotting impairment with the haematologists and give cryoprecipitate or FFP before surgery. 1. Suture-ligate bleeding points with a fine suture or apply haemostats to any obvious bleeding vessels and ligate them. 2. Aspirate any bile collections and attempt to ligate or suture any leaking bile ducts. 3. If major bleeding starts again, attempt to identify the main vessel and suture it. On rare occasions you may carry out lobectomy (see below) if the injury is confined to one lobe. 4. Occasionally, following a severe blunt crushing injury, the damage is so great that no surgical procedure can save the patient’s life, even in the most expert of hands. 1. Piper GL, Peitzman AB. Current management of hepatic trauma. Surgery Clinics of North America 2010;90:775–85. 2. Kozar RA, McNutt MK. Management of adult blunt hepatic trauma. Curr Opin Crit Care 2010 Sep 9 (E-pub ahead of print). 3. Badger SA, Barclay R, Campbell P, et al. Management of liver trauma. World J Surg 2009;33:2522–37. 4. Milla DJ, Brasel K. Current use of CT in the evaluation and management of injured patients. Surgery Clinics of North America 2011;91:233–48. 1. The commonest indication for liver resection is primary or secondary malignancy. Hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, gall bladder carcinoma and colorectal liver metastases are the most frequent indications for liver resection. Benign diseases such as cavernous haemangioma, adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia and cystic diseases may occasionally require liver resection. Rarely, liver resection may be required for managing liver injuries. Over the last two decades, liver resection has been increasingly used to procure part of the liver from living donors for liver transplantation. 2. The treatment of hepatobiliary cancers should be discussed at a specialist multidisciplinary meeting involving surgeons, hepatologists, oncologists and interventional radiologists. 3. Do not undertake an elective operation on the liver without complete preoperative investigation and a fairly certain working diagnosis. Occasionally, an isolated hepatic lesion may be identified during a scan carried out for another reason. If you discover a lesion in the liver during a laparotomy, carefully consider the risks before trying to excise or biopsy it. Operating on a patient with impaired liver function can be very hazardous and carries a high morbidity and mortality. 4. The preoperative workup should start with a detailed history and physical examination of the patient. Liver resection in the presence of underlying chronic liver disease is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Look for signs of chronic liver disease on examination. 5. Carry out biochemical liver function tests, blood count and clotting profile. Underlying chronic liver disease should be suspected if there is an elevated bilirubin, low albumin, increased prothrombin time or low platelet count. Check the tumour markers alfa-feto protein (primary liver cancer) and carcinoembryonic antigen (gastrointestinal cancers) if you suspect a malignant lesion. If chronic liver disease is suspected, carry out hepatitis virus and autoimmune antibody screens. 6. Ultrasound (US) is usually the initial imaging modality for patients presenting with abdominal pain or jaundice. US is useful in assessing the size of the liver and bile ducts, confirming gall stones and detection of ascites, and may show a tumour mass in the liver. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are optimal investigations for characterizing the nature of liver lesions, assessing resectability and tumour staging. CT and MRI may demonstrate features of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis and can accurately quantify the volume of the liver remnant following resection. 7. Angiography demonstrates hepatic vascular anatomy and vascular involvement by tumour, which often dictates whether resection is feasible. CT angiography and MR angiography have high diagnostic accuracy and conventional angiography is rarely used nowadays. 8. When CT and MRI findings are equivocal in the diagnosis or staging of malignancy, PET scan may be of use. However, there is no role for the routine use of PET in the diagnosis or staging of hepatobiliary malignancies. 9. Inadequate volume of the liver remnant can lead to hepatic insufficiency after extended right or left hepatectomies. In such instances, consider preoperative portal vein embolization to increase the volume of the future liver remnant. This is performed in the radiology suite by an interventional radiologist. Through a percutaneous transhepatic route the desired portal vein segments are embolized with embolic agents such as polyvinyl alcohol, foam particles or coils. If radiological expertise is not available surgical ligation of the desired branches of portal vein can be performed, although it complicates subsequent definitive surgery because of hilar scarring. 10. Laparoscopy is an important part of the staging of primary liver and biliary tract malignancies as it can detect peritoneal disease which is often overlooked by both CT and MRI. Tru-cut biopsy of the future remnant liver can be obtained at laparoscopy to exclude underlying parenchymal liver disease. 11. Be cautious about performing percutaneous biopsies of resectable liver tumours. There is now good evidence that malignant cells can seed along the biopsy track. Current CT and MRI technology is highly accurate in diagnosing malignant lesions and histological confirmation is not required prior to resection. Biopsy may be required for histological confirmation of malignancy before commencing palliative treatment in patients with unresectable disease. 12. In patients with liver tumours and a background of chronic liver disease consider wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP) measurements. WHVP corrected for inferior vena caval pressure gives an estimate of portal venous pressure: it increases in portal hypertension secondary to chronic liver disease and is an independent predictor of poor outcome after liver resection. 13. Before undertaking any operative procedure on a patient with chronic liver disease, check the blood film, platelet count and clotting profile and correct any abnormality, if possible by giving blood products. Rarely are platelet infusions necessary, but all patients undergoing liver surgery, especially if jaundiced or with severe biochemical dysfunction, benefit from injections of vitamin K1. If the clotting profile is badly deranged, the patient may need an infusion of FFP and occasionally cryoprecipitate. 1. Select an area of diseased liver or an edge that presents easily through the incision. 2. Place two mattress stitches of 3/0 Vicryl or PDS on an atraumatic round-bodied needle to form a V, the apex of this pointing towards the hilum of the liver (Fig. 17.2A). 3. Gently but firmly tie these stitches (Fig. 17.2B) and remove the wedge of tissue between them with a sharp knife (Fig. 17.2C). The cut edges of the liver should be dry. Insert another suture of similar material if haemostasis is not complete or use diathermy coagulation to establish haemostasis. 4. You may also use a Tru-cut needle to take a liver biopsy. If you are not familiar with the needle, rehearse your movements before inserting it into the liver. After removing the needle, check that you have an adequate core of tissue. Gently shake or tease the core of tissue into a pot of formalin, taking care not to crush it. The puncture site occasionally requires a figure-of-eight or Z-stitch with 4/0 Vicryl or PDS to obtain haemostasis. 1. Open surgical drainage of liver abscesses is rarely necessary. The standard treatment is a prolonged course of antibiotics along with aspiration of the pus under ultrasound guidance as the abscess matures or liquefies. 2. Until the exact nature and antibiotic sensitivities of the causative organism are known, administer intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics such as co-amoxiclav, carbapenem or cephalosporin empirically. 3. Liver abscesses require prolonged treatment which can usually be carried out as an outpatient. Continue antibiotics and US surveillance with admission for US-guided aspiration if clinically septic or the abscess is increasing in size. 4. You may have to aspirate the abscess several times, but if it fails to respond to repeated aspiration and antibiotics or the percutaneous insertion of a drain, then very rarely you may be forced to operate. Localize the abscess first with ultrasound or CT scans. Administer intravenous antibiotics. Cross-match four units of blood and have available FFP. Use intra-operative ultrasound, if available, to identify the site of an intrahepatic lesion.

Liver and portal venous system

TRAUMA

Appraise

EXPLORATION OF A DAMAGED LIVER

Prepare

Access

Assess

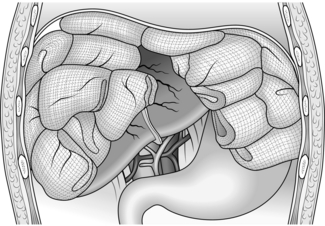

Action

Check

Closure

Aftercare

RE-EXPLORATION

Prepare

Action

REFERENCES

PRINCIPLES OF ELECTIVE SURGERY

Appraise

BIOPSY OR RESECTION OF A LIVER LESION FOUND AT THE TIME OF LAPAROTOMY

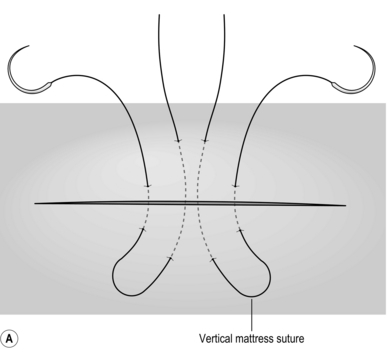

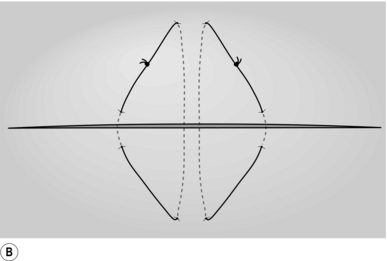

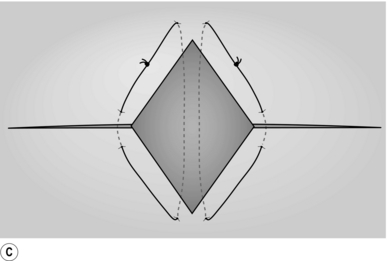

Action

INFECTIVE LESIONS

BACTERIAL LIVER ABSCESS

Appraise

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Liver and portal venous system