13 Liver and biliary tract disease

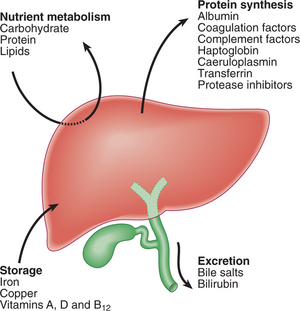

The liver is the largest organ in the body and performs many important functions (Fig. 13.1). Cirrhosis caused more than 25 000 deaths in the USA in 2003. In the developed world, the most common cause of liver disease is alcohol abuse. In contrast, in the developing world, infections caused by hepatitis viruses and parasites are responsible for most chronic liver disease and hepatobiliary cancer.

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

‘ASYMPTOMATIC’ ABNORMAL LIVER FUNCTION TESTS (LFTs)

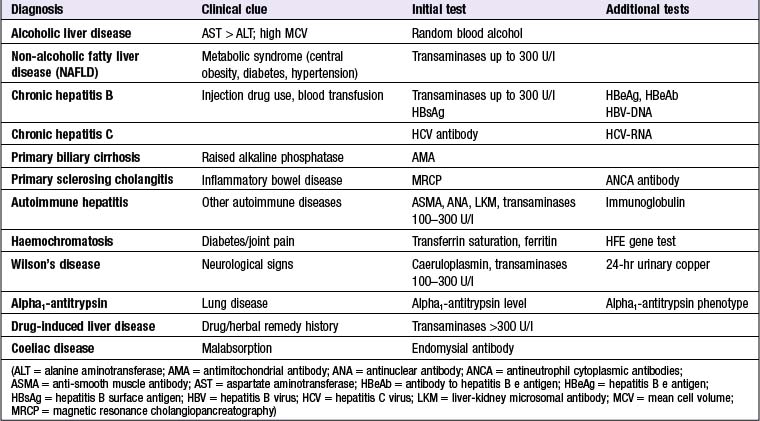

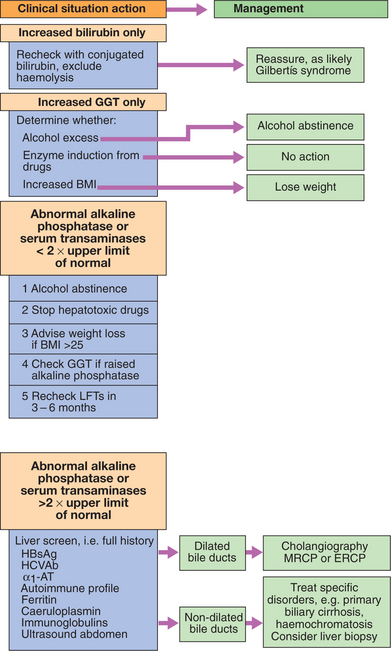

When LFTs are measured routinely prior to elective surgery, 3.5% of patients will have some elevation of transaminase concentrations. The majority of patients with persistently abnormal LFTs have significant liver disease. The most common abnormality is alcoholic or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (pp. 506 and 507). Most hepatologists investigate patients with LFT results greater than twice the limit of normal. The investigations that make up a standard liver screen and additional or confirmatory tests are shown in Box 13.1. An algorithm for investigating abnormal LFTs is illustrated in Figure 13.2. The presence or absence of stigmata of chronic liver disease (p. 492) does not reliably identify patients with significant chronic liver disease. Also, normal LFTs do not exclude significant chronic liver disease, which might progress to cirrhosis, e.g. primary sclerosing cholangitis, haemochromatosis and chronic hepatitis C.

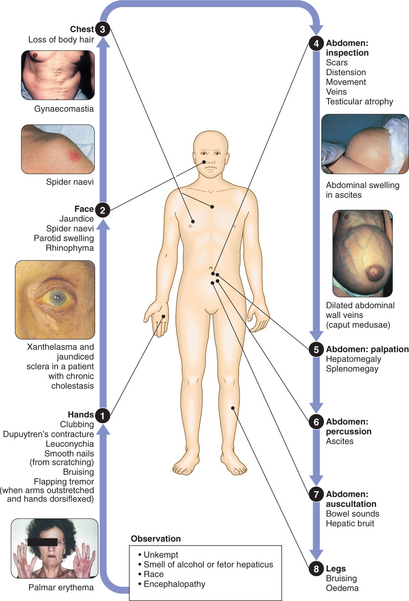

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE ABDOMEN FOR LIVER AND BILIARY DISEASE

JAUNDICE

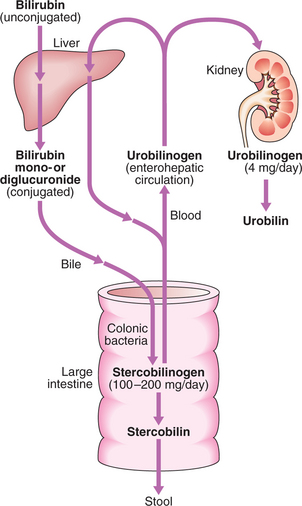

Bilirubin metabolism

Bilirubin in the blood is normally almost all unconjugated and, because it is not water-soluble, it is bound to albumin and does not enter the urine. Unconjugated bilirubin is conjugated by glucuronyl transferase into water-soluble conjugates which are exported into the bile. The excretion pathways for bilirubin are shown in Figure 13.3.

HAEMOLYTIC JAUNDICE

This results from increased destruction of red blood cells or their precursors, causing increased bilirubin production. Jaundice due to haemolysis is usually mild because (except in the newborn) a healthy liver can excrete a bilirubin load six times greater than normal before unconjugated bilirubin accumulates in the plasma. Increased excretion of bilirubin and hence stercobilinogen leads to normal-coloured or dark stools, and increased urobilinogen excretion causes the urine to turn dark on standing as urobilin is formed. The plasma bilirubin is usually <100 μmol/l (∼6 mg/dl) and the LFTs are otherwise normal. There is no bilirubinuria because the hyperbilirubinaemia is predominantly unconjugated. Pallor and splenomegaly are common and blood examination may show evidence of haemolytic anaemia (p. 543).

CONGENITAL NON-HAEMOLYTIC HYPERBILIRUBINAEMIA

Familial Gilbert’s syndrome is the only common cause, resulting from an autosomal dominant mutation reducing expression of UDP-glucuronyl transferase. This causes decreased bilirubin conjugation, with isolated accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. It has an excellent prognosis and needs no treatment.

ASCITES

Ascites means the accumulation of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity and is usually due to malignant disease, cirrhosis or heart failure; however, primary disorders of the peritoneum and visceral organs can produce ascites, and these need to be considered, even in a patient with chronic liver disease (Box 13.2).

Clinical assessment

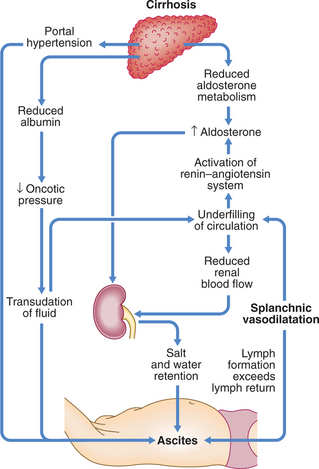

Pathogenesis of ascites in cirrhosis

Splanchnic vasodilatation, mediated mainly by nitric oxide, is thought to be the main factor leading to ascites in cirrhosis. Systemic arterial pressure falls due to splanchnic vasodilatation as cirrhosis advances, with activation of the renin–angiotensin system, secondary aldosteronism, increased sympathetic nervous activity, increased atrial natriuretic hormone secretion and altered activity of the kallikrein–kinin system (Fig. 13.4). These systems tend to normalise arterial pressure but produce salt and water retention. The combination of splanchnic arterial vasodilatation and portal hypertension alter intestinal capillary permeability, promoting fluid accumulation within the peritoneum.

Investigations

Management

Successful treatment of ascites relieves discomfort but does not prolong life, and if over-vigorous, can produce serious disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance and precipitate hepatic encephalopathy (p. 489).

Paracentesis: Large-volume paracentesis with i.v. albumin can be used as first-line treatment of refractory ascites or when other treatments fail.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunts (TIPSS, p. 497): Can relieve resistant ascites but do not prolong life.

SPONTANEOUS BACTERIAL PERITONITIS (SBP)

Patients with cirrhosis are very susceptible to ascitic fluid infection.

Treatment should be started immediately with broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as cefotaxime. Recurrence of SBP is common and may be reduced by prophylactic quinolones such as norfloxacin (400 mg daily) or ciprofloxacin (250 mg daily).

HEPATIC (PORTOSYSTEMIC) ENCEPHALOPATHY

Clinical assessment

The earliest features are very mild and easily overlooked but mental impairment increases as the condition becomes more severe (Box 13.4). Precipitating causes include trauma, drugs, infection, protein load (including GI bleeding) and constipation. Examination usually shows:

13.4 CLINICAL GRADING OF HEPATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY ![]()

| Clinical grade | Clinical signs |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Poor concentration, slurred speech, slow mentation, disordered sleep rhythm |

| Grade 2 | Drowsy but easily rousable, occasional aggressive behaviour, lethargic |

| Grade 3 | Marked confusion, drowsy, sleepy but responds to pain and voice, gross disorientation |

| Grade 4 | Unresponsive to voice, may or may not respond to painful stimuli, unconscious |

Management

Episodes of encephalopathy are common in cirrhosis and are usually readily reversible until the terminal stages are reached. The principles of management are to treat or remove precipitating causes and to suppress production of neurotoxins by bacteria in the bowel. Lactulose (15–30 ml 8-hourly) is a disaccharide which is taken orally and produces an osmotic laxative effect. It reduces the colonic pH, thereby limiting colonic ammonia absorption, and promotes the incorporation of nitrogen into bacteria. Neomycin (1–4 g 4–6-hourly) acts by reducing the bacterial content of the bowel. Dietary protein restriction is rarely needed and can lead to worsening nutritional state in already malnourished patients.

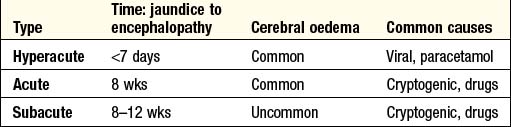

ACUTE LIVER FAILURE

Acute liver failure is an uncommon syndrome in which hepatic encephalopathy, characterised by mental changes progressing from confusion to stupor and coma, results from a sudden severe impairment of hepatic function (Box 13.5). Any cause of liver damage can produce acute liver failure, provided it is sufficiently severe.

Acute viral hepatitis is the most common cause world-wide. Paracetamol toxicity (p. 37) is the most frequent cause in the UK. Acute liver failure occurs occasionally with other drugs, or from Amanita phalloides (mushroom) poisoning, in pregnancy, in Wilson’s disease, or following shock (p. 22). The cause remains unknown in others; these patients are often labelled as having non-A–E viral hepatitis or cryptogenic acute liver failure.

Clinical assessment

Investigations

Investigations are used to determine the cause of the liver failure and the prognosis (Boxes 13.6 and 13.7).

Management

A patient with acute hepatic damage should be observed in a high-dependency or intensive care unit as soon as a progressive prolongation of the prothrombin time or hepatic encephalopathy is identified, so that prompt treatment of complications (hypoglycaemia, infections, renal failure, metabolic acidosis) can be initiated. Treatment is supportive in the hope that hepatic regeneration will occur. N-acetylcysteine therapy may improve outcome, particularly in patients with acute liver failure due to paracetamol poisoning. Liver transplantation is an increasingly important treatment option. Patients with a poor prognosis (Box 13.7) should, wherever possible, be transferred to a transplant centre early to allow time for assessment and to maximise the time for a donor liver to become available. Survival following liver transplantation for acute liver failure is improving and 1-yr survival rates of ∼60% can be expected.

CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

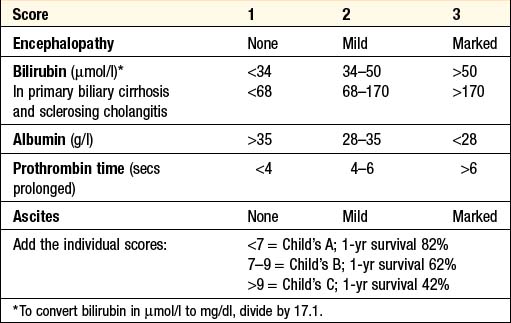

CIRRHOSIS

Any condition leading to persistent or recurrent hepatocyte death may lead to hepatic cirrhosis (Box 13.8). World-wide, the most common causes are viral hepatitis and alcohol. Prolonged biliary damage or obstruction, as can occur in primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis and post-surgical biliary strictures, will also result in cirrhosis.

Clinical features

PORTAL HYPERTENSION

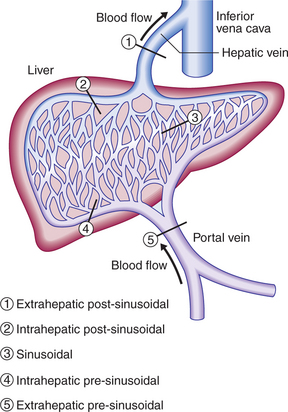

Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction is the usual cause of portal hypertension in childhood and adolescence, while cirrhosis causes 90% or more of portal hypertension in adults in developed countries. Schistosomiasis is a common cause of portal hypertension world-wide but it is infrequent outside endemic areas. Other causes are shown in Box 13.10 and Figure 13.5. Increased portal vascular resistance leads to a gradual reduction in the flow of portal blood to the liver and simultaneously to the development of collateral vessels, allowing half or more of the portal blood to bypass the liver and enter the systemic circulation directly.

13.10 CAUSES OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION ACCORDING TO SITE OF ABNORMALITY ![]()

Extrahepatic pre-sinusoidal 5

Clinical features

VARICEAL BLEEDING

Management of acute variceal bleeding

See also acute upper GI haemorrhage (p. 418).

Balloon tamponade: Employs a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube possessing two balloons which exert pressure in the fundus of the stomach and in the lower oesophagus respectively. Current modifications, such as the Minnesota tube, have additional lumens to allow aspiration from the stomach and from the oesophagus above the oesophageal balloon. Gentle traction is essential to maintain pressure on the varices. Initially, only the gastric balloon should be inflated with 200–250 ml of air, as this will usually control bleeding. Inadvertent inflation of the gastric balloon in the oesophagus causes pain and can lead to oesophageal rupture. If the oesophageal balloon needs to be used because of continued bleeding, it should be deflated for 10 mins every 3 hrs to avoid oesophageal mucosal damage. Pressure in the oesophageal balloon is maintained at <40 mmHg using a sphygmomanometer. Balloon tamponade will almost always stop variceal bleeding, but only creates time for the use of definitive therapy. Patients unable to protect their airway should be intubated to avoid pulmonary aspiration whilst the tube is inserted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree