CHAPTER 68 Liver

The liver is the largest of the abdominal viscera, occupying a substantial portion of the upper abdominal cavity. It occupies most of the right hypochondrium and epigastrium, and frequently extends into the left hypochondrium as far as the left lateral line (Fig. 68.1). As the body grows from infancy to adulthood the liver rapidly increases in size. This period of growth reaches a plateau around 18 years and is followed by a gradual decrease in the liver weight from middle age. The ratio of liver to body weight decreases with growth from infancy to adulthood. The liver weighs approximately 5% of the body weight in infancy and it decreases to approximately 2% in adulthood. The size of the liver also varies according to sex, age and body size. It has an overall wedge shape, which is in part determined by the form of the upper abdominal cavity into which it grows. The narrow end of the wedge lies towards the left hypochondrium, and the anterior edge points anteriorly and inferiorly. The superior and right lateral aspects are shaped by the anterolateral abdominal and chest wall as well as the diaphragm. The inferior aspect is shaped by the adjacent viscera. The capsule is no longer thought to play an important part in maintaining the integrity of the shape of the liver.

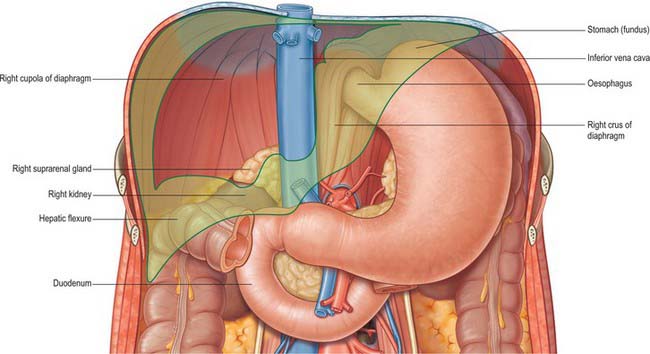

Fig. 68.1 The ‘bed’ of the liver. The outline of the liver is shaded green. The central bare area is unshaded.

SURFACES OF THE LIVER

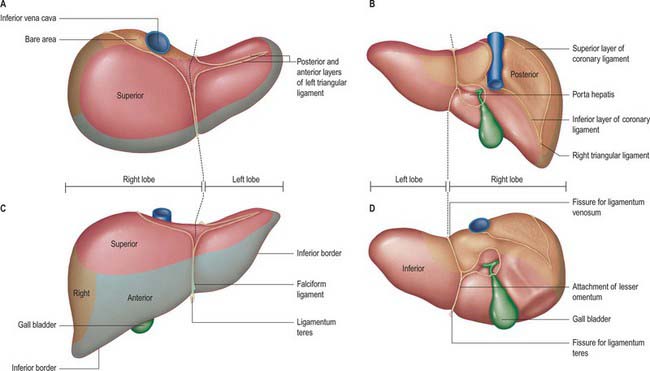

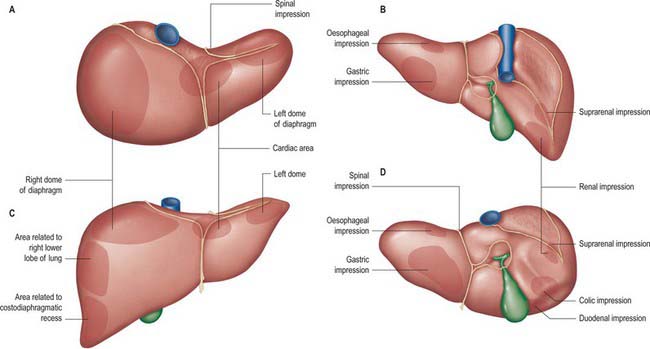

The liver is usually described as having superior, anterior, right, posterior and inferior surfaces, and has a distinct inferior border (Figs 68.2, 68.3). However, the superior, anterior and right surfaces are continuous and no definable borders separate them. It would be more appropriate to group them as the diaphragmatic surface, which is mostly separated from the inferior, or visceral surface, by a narrow inferior border. At the infrasternal angle the inferior border is related to the anterior abdominal wall and is accessible to examination by percussion, but is not usually palpable. In the midline, the inferior border of the liver is near the transpyloric plane, about a hand’s breadth below the xiphisternal joint. In women and children the border often projects a little below the right costal margin.

Fig. 68.3 Relations of the liver. A, superior view; B, posterior view; C, anterior view; D, inferior view.

The posterior surface is convex, wide on the right, but narrow on the left. A deep median concavity corresponds to the forward convexity of the vertebral column close to the attachment of the ligamentum venosum. Much of the posterior surface is attached to the diaphragm by loose connective tissue, forming the triangular ‘bare area’. The inferior vena cava lies in a groove or tunnel in the medial end of the ‘bare area’. To the left of the caval groove the posterior surface of the liver is formed by the caudate lobe, and covered by a layer of peritoneum continuous with that of the inferior layer of the coronary ligament and the layers of the lesser omentum. The caudate lobe is related to the diaphragmatic crura above the aortic opening and the right inferior phrenic artery, and separated by these structures from the descending thoracic aorta.

The fissure for the ligamentum venosum separates the posterior aspect of the caudate lobe from the main part of the left lobe. The fissure cuts deeply in front of the caudate lobe and contains the two layers of the lesser omentum. The posterior surface over the left lobe bears a shallow impression near the upper end of the fissure for the ligamentum venosum that is caused by the abdominal part of the oesophagus. The posterior surface of the left lobe to the left of this impression is related to part of the fundus of the stomach. Together these posterior relations make up what is sometimes referred to as the ‘bed’ of the liver (Fig. 68.1).

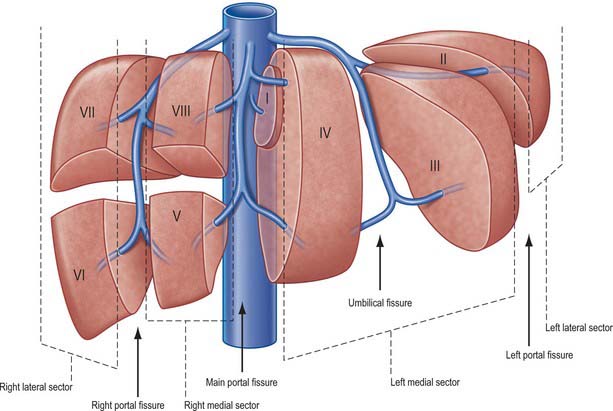

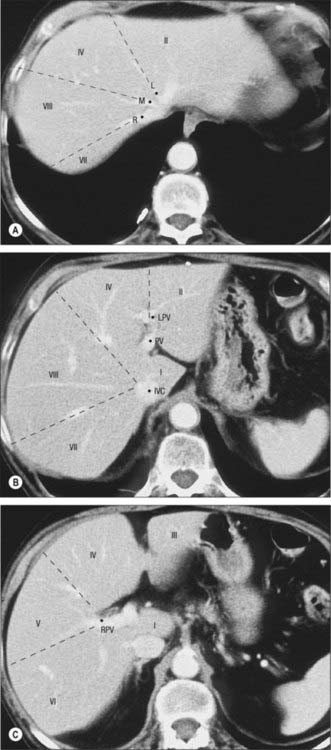

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMICAL DIVISIONS

Current understanding of the functional anatomy of the liver is based on Couinaud’s division of the liver into eight (subsequently nine) functional segments, based upon the distribution of portal venous branches and the location of the hepatic veins in the parenchyma (Couinaud 1957). Further understanding of the intrahepatic biliary anatomy, especially of the right ductal system, was enhanced by contributions from Hjortsjo (1948) and Healey & Schroy (1953) using the biliary system as the main guide for division of the liver (Fig. 68.4).

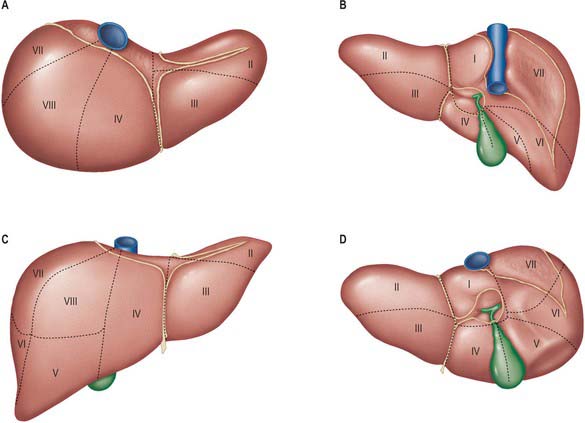

Sectors and segments of the liver

Sectors

The sectors of the liver are made up of between one and three segments: right lateral sector = segments VI and VII; right medial sector = segments V and VIII; left medial sector = segments III and IV (and part of I); left lateral sector = segment II (Fig. 68.5). Segments are numbered in an ante-clockwise spiral centered on the portal vein with the liver viewed from beneath, starting with segment I up to segment VI, and then back clockwise for the most cranial two segments VII and VIII (Fig. 68.6).