Overview

The law is not a simple set of rules; judgement is required against a background of understanding

Understanding the legal duties on the employer will ensure that occupational health advice will aid compliance

Occupational health advice in employment cases must be fair and justifiable, not least because the practitioner can be called to a tribunal

Recruiting people with a disability can be challenging. Managing them in the workplace means occupational health advice needs to be underpinned by a thorough understanding of relevant law

Fear of litigation or concerns that when things go wrong there is automatically negligence can drive poor decisions

Introduction

Health and safety in the workplace is underpinned by legal duties upon employers to protect the workforce. Many elements of health and safety law fall within the expertise of the occupational health professional (OHP). There has also been a shift towards advising management about human resource issues, which makes an OHP’s understanding of employment law and disability all the more important. These legal matters are technically complex, so it is important for OHPs to have a good understanding of relevant areas.

The UK Legal System

The UK has a common law jurisdiction, which means that court decisions set precedent, binding future decisions and developing the law. Most civil law, including the area of tort (a civil wrong), has been built in this way. Opinions of higher courts (the highest being the Supreme Court from 2009, previously the House of Lords) are binding on those below. By contrast most criminal law is laid out in statute (Table 5.1). Acts of Parliament tend to be enabling, in that details will be developed beneath in regulations (statutory instruments). Codes of Practice often accompany which, whilst not themselves the law, will be regarded as a breach of the law if not followed.

Table 5.1 Civil and criminal law

| Civil law | Criminal law |

| Developed by court decisions | Statute from Parliament |

| Disputes between individuals | State prosecutes individuals |

| Corrects using compensation | Punitive |

| On the balance of probabilities | Beyond reasonable doubt |

Health and Safety Law

Current UK health and safety law has developed from the 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act. This ‘umbrella’ statute lays out general duties and the foundations for a risk based approach to managing workplace hazards (Box 5.1).

- safe systems of work

- provision of information, instruction, training and supervision

- maintenance of the workplace and safe access and egress

- a working environment that is safe, without risks to health, and adequate as regards welfare.

- take reasonable care for the health and safety of themselves and others

- cooperate with their employers.

European Influence

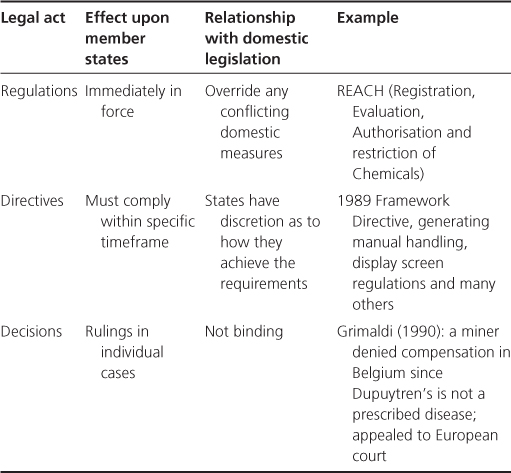

Adoption of the Single European Act in 1987 allowed the European Union (EU) to issue directives on, among other things, health and safety standards. This has since generated considerable UK domestic legislation, with regulations covering work equipment, noise, manual handling and display screens (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 The influence of Europe

Duty of Care

The general principle is that those who generate risk as a consequence of work activities have a duty to protect anyone who may be affected. The extent of this duty in statute is commonly ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’. This allows the employer to balance the degree of risk against the cost and difficulty of controlling it. A small employer with modest resources may reasonably argue reduced action in comparison with a large multinational. However, it is for the employer as the defendant to convince the court that he could not have done more; a reversal of the normal burden of proof in criminal cases.

‘Reasonably practicable’ has been defined more narrowly as a term than ‘physically possible’. The risk must be real rather than hypothetical, and an employer can use industry standards and his own experience as a guide.

Prosecution

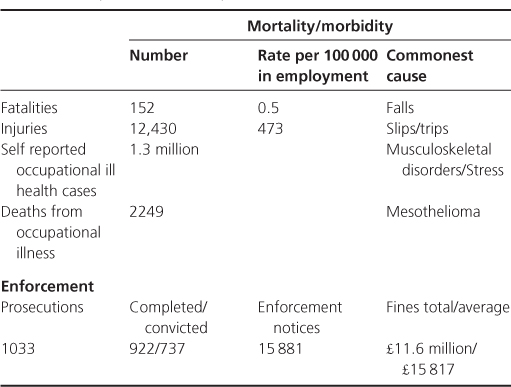

In the UK, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Local Authorities are responsible for enforcing the 1974 Act. Inspectors have powers to issue improvement or prohibition notices, or prosecute. Prosecution generally results in a fine (Table 5.3).

Table 5.3 Key Health and Safety Executive data 2009/10

Larger fines, intended to reflect the severity of the incident, tend to be the only ones to reach public awareness. For instance, the Buncefield fire in 2005 (Figure 5.1) resulted in prosecution by the HSE of five companies. Of these, Total UK was fined £3.6 million plus £2.6 million costs.

Where cases involve fatalities, they are referred to the Crown Prosecution Service.

Occupational Injury and Disease

Fatal and major injuries and occupational disease are reported to the HSE under the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 1995 (RIDDOR). Only medical conditions that are listed are reportable, and then only if the affected worker is involved in a relevant activity and the diagnosis is confirmed by a doctor.

Corporate Manslaughter

The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 introduced the concept of ‘management failure’, if the way in which the business was organized fell well below that which was reasonably to be expected and resulted in a fatality. This replaced the requirement to identify the ‘controlling mind’ within a company who could be held personally liable. The latter principle had proved impossible to apply to large businesses, such as P&O following the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. Smaller companies fared differently, as with the 1993 Lyme Bay kayaking tragedy in which four teenagers drowned. Peter Kite, one of the company’s directors, was sentenced to 3 years imprisonment as a result.

The new Act removes the requirement to find all the blame in one person; however, this has not resulted in any great change and the Centre for Corporate Accountability, an organisation committed to monitoring activity in this area, closed because of funding difficulties in March 2009. A number of fatalities have occurred since the introduction of the Act in April 2008, and lesser charges brought. In February 2011, Cotswold Geotechnical Holdings Ltd and its managing director became the first company to be convicted of the new offence of corporate manslaughter. This case concerned the death in 2008 of Alex Wright, a junior geologist crushed when an excavation collapsed upon him.

The Health and Safety (Offences) Act 2008 also allows senior management or directors to be given custodial sentences for non-fatal offences.

Civil Law

An employee may obtain compensation for the tort, or wrong, that has occurred, if their employer is found to have negligently allowed him to suffer injury or illness.

The applicant employee has to show that:

- the employer owed him a duty of care

- the employer negligently breached that duty

- the employee suffered damage caused by that breach.

Only an estimated 10% of claimants are successful. Damages are generally modest, especially when legal fees and clawback of certain previously paid state benefits are taken into account.

Conditional fee arrangements (no win no fee) make it easier to pursue such a claim, since failure will not incur legal costs. However, this does mean that law firms will tend only to take on cases which stand a good chance of success.

Issues

Duty of care. The duty of care upon the employer is roughly equivalent to that in the criminal courts. The court will take a number of factors into account, including the vulnerability of the individual employee; the employer has a greater duty to safeguard that person (Table 5.4). It may also be that at the time that the harm was caused, the risk of the condition was genuinely not appreciated. The court will set a ‘date of knowledge’ from which a reasonable employer would have been expected to be aware.

Table 5.4 Employers duty of care in the civil courts

| Issue | Case | Details |

| Extent of duty | Stokes v GKN 1968 | ‘The overall test is still the conduct of the reasonable and prudent employer, taking positive thought for the safety of his workers… ’ |

| Increased duty toward vulnerable workers | Paris v Stepney Borough Council 1951 | This fitter suffered a penetrating eye injury. He was already monocular, and the employer was negligent in not providing goggles, which were not felt necessary for the rest of the workforce since the risk was small |

| Volenti non fit injuria is the phrase used when an employee elects to put themselves at risk in the workplace and forgo the right to claim compensation in the event of loss, harm or injury | Smith v Baker and Sons (1891) | The courts are unlikely to judge in favour of an employer when loss, harm or injury does occur, as they would need to show that the employee:

|

| Smith was a quarryman working beneath a crane, although the crane was not always operating. The crane dropped a rock on to Smith injuring him. It was suggested that Smith knew about the danger, but the judgement was in Smith’s favour when it was revealed that he was threatened with dismissal if he refused to work under the crane. | ||

| Lord Hershell, obiter: ‘… that where a servant has been subjected to risk owing to a breach of duty on the part of his employer, even though he knows of the risk and does not remonstrate, does not preclude his recovering in respect of the breach…’ |

Work-related stress cases. These tend to be of concern to the employer. The landmark decision was Walker v. Northumberland County Council in 1995. The key point concerning Mr Walker, a social worker, was that following an acute mental illness and prolonged absence, he returned to work with assurances of changes in work design to support him. When these failed to materialize he suffered a second episode of mental illness. It was the failure to foresee and prevent the second episode for which the council were found liable. The law has developed only slightly since then (Table 5.5).

Table 5.5 Work-related stress cases of note

| Case | Detail | Legal point |

| Sutherland v Hatton (2002) | Mrs Hatton was a French teacher who was retired on ill-health grounds in 1996. She argued that teaching is intrinsically stressful and that the school governors should have had better support measures in place. Three other cases of work-related stress were brought in the same appeal | Sixteen ‘practical propositions’ were handed down by the court. Among them was the view that if a confidential advice service, with appropriate counselling or treatment services, were in place, the employer would be unlikely to be found liable |

| Barber v Somerset County Council (2004) | One of the four cases in the above judgement was referred to the House of Lords. Mr Barber was a mathematics teacher who became ill with depression and panic attacks in 1996. This culminated in him physically shaking a pupil | Approved the Court of Appeal propositions, but disagreed in respect of Mr Barber. Their conclusion was that after his first sickness absence, his employer should at least have made ’sympathetic enquiries’ and considered what could have been done to help |

| Intel v Daw (2007) | Tracy Daw was promoted shortly after her return to work following childbirth (and her second episode of postnatal depression). Soon after that there was a organisational restructure. Her reporting lines were confused and she had a breakdown in 2001, arguing that her workload was excessive and employer gave her insufficient assistance | Her employer argued that she could have used their confidential counselling service but did not. The Court of Appeal held that where an employee is experiencing stress relating to excessive workloads, the presence of a workplace counselling service will not automatically serve to discharge the employer’s duty of care in stress claims |

| Dickins v O2 plc (2008) | Following an office move and change of work, Susan Dickins found herself with a long and stressful commute and stressful job. Her request for a transfer or sabbatical was not acted upon, and she went sick with stress and was dismissed | She should have been referred to occupational health and properly assessed, which should then have guided management actions |

Compensation; Government Scheme

The industrial injuries scheme administered by the UK Department of Work and Pensions ‘prescribes’ a number (currently about 70) of occupational illnesses for compensation as well as injuries sustained at work. The claimant must also have worked in an occupation recognized to carry a risk of that particular condition. Their claim will be assessed and paid on the basis of the percentage disablement. Rates vary up to a maximum (100% disability) of £127.10 weekly benefit (2006 figure).

Employment Law

The fundamental positions of the two parties—employer and employee—in the contract of employment are consolidated in the Employment Rights Act 1996. There are also influential relevant codes of practice, such as those produced by the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS).

Enforcement

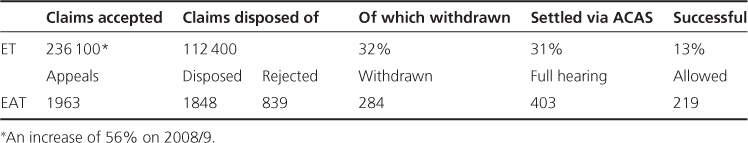

Complaints are heard by Employment Tribunals (ETs). These consist of three members: a legally qualified chair and two lay members who represent employers associations and employee organisations. ETs were established in 1964 so that employment disputes could be settled rapidly without the expense of court proceedings. They are now extremely busy (Table 5.6).

Table 5.6 Employment Tribunal (ET) and Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) activity 2009/10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree