David Copenhaver, MD, MPH, Wesley Prickett, MD, and Scott M. Fishman, MD

99

INTRODUCTION

The American Institute of Medicine, in a landmark report entitled Relieving Pain in America, estimated that chronic pain affects nearly 100 million American adults. Concomitantly, a marked escalation in opioid prescriptions has been noted nationally. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that prescription drug overdose, predominantly involving opioids, is the leading cause of accidental death in adults aged 25 to 64. These seemingly contradictory facts have prompted a reevaluation of the indications for the use of opioid therapy. It is essential that health care providers understand the federal and state regulations that govern the use of controlled substances.

FEDERAL REGULATIONS

Federal regulations governing controlled substances are based on two major concepts: (1) truth in labeling and (2) the appropriate distribution/use of controlled substances. Truth in labeling protects consumers from an educational standpoint, and the appropriate use of controlled substances reduces access to these substances, thereby protecting the public at large from drugs of abuse.

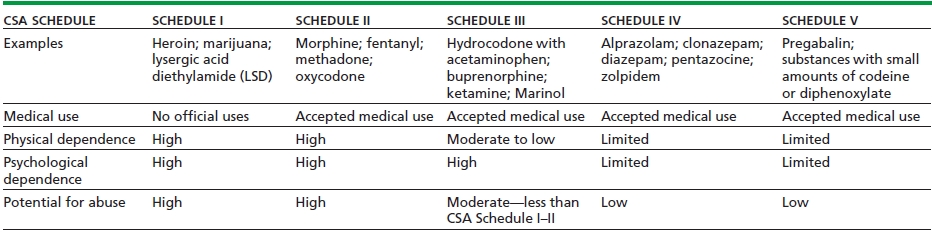

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) is the primary set of federal regulations that govern the medical use of controlled substances in the United States. Under the CSA, controlled substances are divided into five schedules that are predicated on the following characteristics: potential for abuse, pharmacologic effects, known scientific properties, pattern of abuse, public health risk, psychic or physiologic dependence, liability, and whether or not the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already classified under a CSA schedule (Table 99-1).

TABLE 99-1. THE FIVE CSA SCHEDULES AND COMPARISON OF THE CRITERIA FOR SCHEDULE DETERMINATION

Federal regulations allow opioids to be used to treat both acute pain and chronic pain. Methadone and buprenorphine are approved and labeled not only to treat pain but can be prescribed for opioid detoxification and maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Specialized registration as a narcotic treatment program is required in order for physicians to prescribe methadone and buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Physicians who prescribe Suboxone, buprenorphine and naloxone for dependence must attend required educational sessions and subsequently apply for a special waiver from the DEA and fulfill the requirements of the center for substance abuse treatment. Physicians who do not hold this waiver through the DEA have specified limitations under the law and can only administer these substances to an addicted individual to relieve acute withdrawal symptoms for no longer than 72 hours. This grace period allows the physician to refer the patient to a narcotic treatment program. As stipulated by the DEA, only a 1-day supply of medication may be provided per day, and the 3-day period may not be renewed. Physicians must understand the importance of recognizing addiction and reserving the treatment of addiction to those specialized in this discipline.

FEDERAL REGULATIONS AND MARIJUANA

Nineteen states have enacted laws that allow for the provisional use of marijuana recreationally and/or to treat various medical conditions. Proponents of medical marijuana assert that it is an effective treatment for numerous ailments including, but not limited to, pain, glaucoma, nausea, spasticity, appetite stimulation, and movement disorders. The federal government has categorized marijuana as a Schedule I substance. This implies it has no accepted medical use and has a high potential for abuse. There is debate as to whether or not state law can preempt federal law; suffice to say, there is no current resolution to this dilemma.

The use of “state-legalized” medical marijuana by pain patients places opioid-prescribing practitioners in a precarious position. Physicians are regulated by both state and federal regulations and are expected to comply with both regulations. In the case of medical marijuana, the state and federal regulations are conflicting, which leaves prescribers caught in the middle. Legal precedence would suggest adherence to the more conservative federal regulations.

THE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY

Health care providers who wish to prescribe controlled substances must be registered and obtain a provider number through the DEA. The DEA is part of the U.S. Department of Justice and does not directly regulate medical practice, but does investigate practitioners who do not comply with the laws regarding distribution of controlled substances. These investigations can lead to revocation of the provider’s DEA number or criminal prosecution.

According to the DEA, common behaviors that result in investigation include issuing prescriptions for controlled substances without a physician–patient relationship, issuing prescriptions in exchange for sex, issuing several prescriptions at once for a highly potent combination of controlled substances, charging fees commensurate with drug dealing rather than providing medical services, and issuing prescriptions using fraudulent names and self-abuse by practitioners.

Federal DEA numbers are valid for 3 years and must be kept at the registered location and be readily retrievable for inspection purposes. Currently, there are no continuing medical education (CME) requirements to obtain a DEA number.

In 2007, the DEA determined that practitioners may provide patients with multiple prescriptions, to be filled sequentially, for the same Schedule II controlled substance. This allows practitioners to provide 90-day supplies of Schedule II medications. In 2010, the DEA permitted practitioners, who are registered with the DEA, to prescribe scheduled substances electronically.

RISK EVALUATION AND MITIGATION STRATEGIES

The Food and Drug Administration has the authority to require manufactures to develop Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) under the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007. The REMS requirement is to ensure that the substance’s benefits outweigh its potential risk.

The manufacturers of the long-acting opioids are required to financially support the development of voluntary CME for their products. On July 7, 2012, the FDA released the final REMS for extended-release/long-acting opioids. Furthermore, the FDA released a REMS for transmucosal immediate release fentanyl (TIRF) on December 29, 2011.

The FDA has also issued several consumer warnings on the disposal of controlled substances. These substances, especially the fentanyl patch, can pose a serious risk for children. These warnings have highlighted the growing necessity for prescribers to educate their patients about the safe use, storage, and disposal of controlled substances. Responsible opioid prescribing necessitates that patient education about these topics be a part of every provider–patient opioid agreement.

STATE REGULATIONS

State medical boards have the sole responsibility of licensing health care providers; therefore, the regulations and requirements regarding licensing can vary significantly from state to state. The state medical boards are also responsible for determining the standards of medical practice and subsequent investigation of practitioners who may be practicing outside these standards.

Multiple professional organizations have published guidelines regarding the use and prescribing of controlled substances. Many states have turned to these recommendations for guidance when drafting state legislation and medical policy. In 2004, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), a national nonprofit organization representing 70 medical and osteopathic boards, released “Model Policy for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain.” This policy document has been utilized by various state medical boards to draft their own policies regarding the treatment of pain and the subsequent use of controlled substances. The FSMB released an extensive update of this policy in May 2013.

State medical policy can vary widely from state to state, and for this reason, prescribers need to be cognizant of the legal statutes in their state. Some specific state variations of interest include possible limits on the amount of opioids that can be dispensed, listing opioids as a treatment of last resort, requiring that opioids result in documented functional improvement, requirement for evaluation by a pain specialist, or provider CME requirements in opioid prescribing/pain management.

PRESCRIPTION DRUG MONITORING PROGRAMS

Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) have been constructed to aid health care providers and law enforcement personnel in their efforts to prevent the abuse and misuse of controlled substances. PDMP vary dramatically by state, but are all intended to track controlled substance prescriptions. The information recorded by each PDMP is highly variable; some states monitor all scheduled medications, whereas other states only track certain drug schedules. The state agency responsible for the maintenance of the PDMP also varies. Many states have created secure electronic PDMP databases that are accessible by health care providers and/or law enforcement personnel.

Unfortunately, communication between states PDMP is still relatively uncommon. Also, the effectiveness of PDMP on diminishing controlled substance misuse/abuse is difficult to determine due to their high variability, but in many states, PDMP have developed into a critical component of risk management evaluation in the prescribing of controlled substances.

EMERGING OPIOID RISK DATA AND RELEVANT ISSUES

A pronounced shift in the use of opioids to treat chronic noncancer pain has taken place in recent years largely due to the overwhelming evidence describing the intrinsic risk to any opioid analgesic dose. It is now known that more than 6 million Americans abuse prescription drugs and opioid overdose is now the leading cause of accidental death.

These data have caused considerable debate as to the appropriateness of chronic opioid therapy in the treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain and underscore the need for prudent judicious risk stratification when prescribing opioids.

THE RESCHEDULING OF HYDROCODONE

An April 2012 Drug Enforcement Agency report commented that 42 tons of hydrocodone was prescribed in the year 2010, and the DEA has suggested that hydrocodone is one of the top two most abused controlled substances in the United States. The October 2013 FDA decision to shift hydrocodone from Schedule III to the more restrictive Schedule II has critical implications. The current scheduling inaccurately suggests lower abuse potential. The impact of such a shift is expansive, in that the FDA and DEA will send a clear message to physicians as to the abuse potential of such medications and the prudent clinical judgment that must be waged with prescribing such a substance for pain control.

KEY POINTS

1. The CSA is a federal regulation governing the medical use of controlled substances.

2. The FDA has mandated the manufacturers of long-acting opioid preparations and TIRF to develop REMS.

3. Emerging data regarding the risk of chronic opioid therapy for non–cancer-related pain have demonstrated the need for greater vigilance and risk stratification when prescribing opioids.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. What are the primary sets of federal regulations that govern the medical use of controlled substances?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree