10 Legal and professional issues

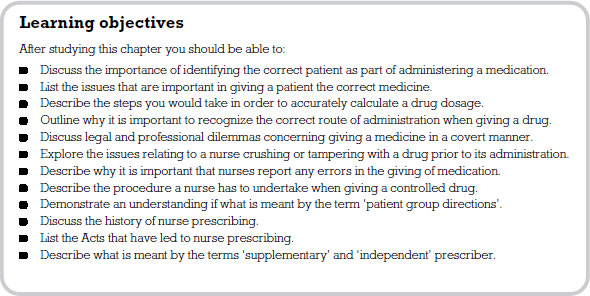

The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to the legal and professional issues faced by nurses in medicines management. Nurses are bound by the code of conduct laid out by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). The NMC has specific standards for administration of medication which must be adhered to. In addition, nurses are governed by the legislation surrounding medicines.

Administration of medicines is a skill that you will be exposed to during your pre-registration education. It is most important that you become involved in this procedure, so that you can become confident and competent as a practitioner. On your placements you need to be assertive in requesting to be involved in the administration of medicines because qualified nurses often carry out this task without necessarily involving the student.

Medicines are used for their therapeutic effects and careful administration of these is paramount. As a result, a number of legislative and professional standards are in place so that mistakes do not occur. In 2008 the NMC set out its latest guidance for the administration of medicines. This guidance highlights the importance of identifying the correct patient, the correct drug, the correct dose, the correct site and method of administration and the correct procedure. This chapter will use this framework to explore certain legal and professional issues that may arise during your initial education. The chapter will conclude by briefly exploring the future of the nurse’s role in medicine management.

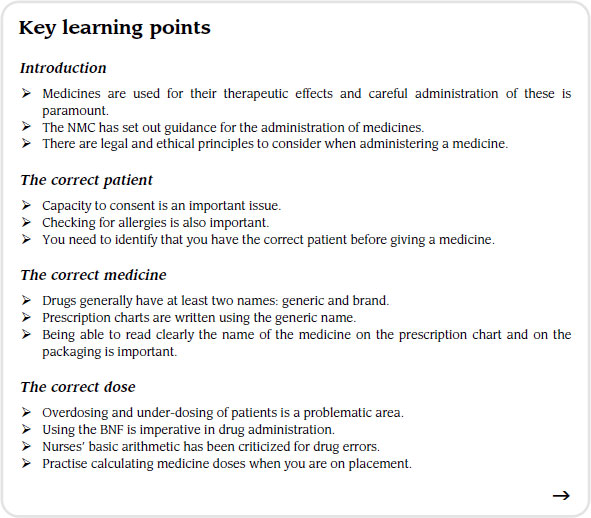

The correct patient

It is essential that you are aware of the relevant details of the person you are about to give a medicine to. For example, you need to know some background on the patient even before correctly identifying them. The first question that you might ask is whether the individual has the capacity to consent. This will be dealt with later in the chapter. You also need to consider the patient’s diagnosis and physical capabilities. An area addressed in previous chapters is also important to consider at this point: the question of hypersensitivity and allergies. There may also be special instructions that are important to remember such as whether the patient is to be kept nil by mouth.

At some point you will be working in a busy acute setting where the turnover of patients is high. In this environment it is unlikely that you will get to know patients very well and the safest way to identify a patient before giving them a medicine is by checking their wrist band (identity band). This band should contain accurate details that correctly identify the wearer.

Between November 2003 and July 2005 the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) received 236 reports of patient safety incidents and cases of ‘near-misses’ relating to missing wristbands or wristbands with incorrect information. Over the period February 2006 to January 2007 the NPSA received 24,382 reports of patients being mismatched to their care. We accept that not all these incidents involved the giving of medication but what these statistics highlight is the importance of thoroughly checking the identity of a patient.

You should find that ‘core patient identifiers’ are on their wristband, such as surname, forename, date of birth and NHS number. In long-term settings you may also find that photographs of patients are provided on their charts to help ensure that problems of misidentification do not occur.

The correct medicine

Most medicines have two names, the generic approved name (e.g. diazepam) and the proprietary or manufacturer’s brand name (e.g. Valium). As a student one of your first tasks is to learn both the generic and proprietary (brand) names. On placement you will find that most health care professionals refer to drugs by their generic name whereas patients often refer to the brand name. The fact that drugs have more than one name makes the potential for error greater.

Prescription charts have to be written up using the drug’s generic name, so limiting the chance for error. However, stocks of drugs on the wards and patients’ individual drug boxes carry both names. You must make sure that when you are checking a drug you are satisfied it is the drug that is named on the prescription sheet. Most nurses would probably agree that medication packaging can be quite misleading and the names that are given to medicines can look and sound very similar. If you are in doubt please ask.

You must make sure you can read the name of the drug clearly, both on the prescription chart and on the packaging it is being dispensed from. You must never transfer drugs from one container to another, nor be tempted to agree to a drug being dispensed from a container which has had the label defaced or altered in some way.

When administering medicines to a patient it is also part of the nurse’s responsibility to ensure that the drug is appropriate for the patient. Knowledge of the patient’s medical history and their medical diagnosis is the main way of determining this, as is discussion with the prescriber and the patient. A patient should only be prescribed a medicine where there is a clinical need, and where non-pharmacological methods have proved insufficient.

Some medicines may be prescribed to a patient for a reason not under the drugs licence remit. This is not abnormal and discussion with the prescriber can reassure the nurse prior to administration that the drug is appropriate. A good example is that of amitriptyline. This drug is well known for treating depression but in more recent times has been prescribed in low doses to alleviate chronic back pain.

The correct dose

Another reason why drug errors occur relates to the potential for overdosing or under-dosing the prescribed medicine. As a nurse the NMC suggests that it is not enough for you to be able to give a drug but that you should have some understanding of what you are giving. Administering a medicine should not be a case of mechanically following a set of instructions but rather an intellectual event that is carried out thoughtfully. When you are involved in the procedure of medicine administration it is good practice to have an understanding of the drug’s actions, interactions and side-effects. It is no defence to simply agree with the giving of the medicine because you trust the doctor or the nurse. You must ensure that you use the BNF in any circumstances where you are unsure. All care settings that dispense drugs must have a copy on hand as a reference for all staff members. Find out where it is kept and make use of it during your placements. Make use of Appendix 1 covering interactions. Some patients are prescribed many medications for multiple conditions so it is important to be aware of any interactions between prescribed and OTC medicines, for example. Many drug combinations may have interactions which are of little or no clinical relevance, but others may have interactions with potentially serious or hazardous consequences. The ultimate responsibility lies with the prescriber, but the pharmacist involved in dispensing medicines and the nurse who administers medicines also have a role in identifying potential interactions for patient safety.

Our advice to you is to learn about a small number of drug groups which you come across regularly on your placement. If you do this for all the placements you visit over your three years you can build up a comprehensive portfolio of information and knowledge.

A number of authors in recent nursing literature suggest that errors occur in medicine administration because of a lack of basic mathematical skills in nurses themselves. Some writers even suggest that pre-filled infusion bags, electronic drip counters and user-friendly drugs such as single-dosed heparin injections all contribute to the deskilling of nurses in terms of their mathematical abilities.

It is true to say that this phenomenon has been recognized by nurse education and steps are being taken to remedy the situation. Since 2000 there has been a drive to increase student nurses’ basic numerical skills. Part of the aim of this book has been to emphasize the importance of calculating accurate doses and to give you the opportunity to practise your maths outside the clinical setting.

In promoting safe practitice, some nurses have called for a greater use of, and emphasis on, calculators within practice settings. However, there is a counter-argument here that suggests we should use calculators less in practice. The thinking behind this is that calculators will become a substitute for the nurse using basic arithmetic. As a student nurse I am sure you will get your fair share of theoretical sessions on numeracy in nursing as part of your pre-registration education. The testing of basic levels of numeracy has now become part of the criteria for entry onto nurse education programmes. If you have not engaged in the calculation exercises in this book we believe you are missing out on a critical area of your knowledge. Most of the questions we have posed are basic in nature and are only included to give you a foundation. However, it is important that we all start somewhere, and the self-testing element of the book gives you an opportunity to get it wrong without undue criticism or pressure.

In practice we suggest that when involved in working out drug calculations you should:

- take time to work out your calculations;

- always recheck your answers;

- do not be rushed by colleagues or be embarrassed to tell them that you get a different answer; answers that look wrong probably are and it might be useful to make an initial logical estimate to base your final calculation on;

- if you are unsure do not be tempted to avoid losing face by simply agreeing for agreeing sake – this is dangerous.

The correct site and method of administration

You will probably have heard the one about the student nurse being asked to give a patient an aminophylline suppository to help their breathing. The sister came back five minutes later to find the student trying to insert the suppository into the patient’s nose! Joking apart, you should be aware of which route the medicine is to be given. To simply ask for a medicine to be given by injection is not specific enough. As you are aware, there are a number of ways in which a drug could be injected: SC, IM or IV.

Recently, a person suffering from leukaemia was receiving regular chemotherapy by IV infusion. A junior doctor, by error, decided to give the medication into the person’s epidural space and subsequently killed them. This situation would have to be dealt with under criminal law and a coroner would be involved. Less extreme examples of getting routes of administration wrong could be the difference in giving a medication sublingually instead of buccally. For example, a drug called glyceryl trinitrate, when prescribed buccally, should be placed under the top lip; but if prescribed sublingually it will be placed under the tongue. Medicines are designed and formulated to be absorbed according to the route of delivery; therefore, getting the route of a drug right is of paramount importance.

Covert administration of medicines

Administration of medicines covertly is a highly contentious issue in nursing. For example, to administer a medicine covertly to a capable adult would, in law, be looked upon as trespass. This is because the person receiving the medicine would not have consented. The Human Rights Act (1998) describes the need for nursing care to be given with respect and to be proportionate to the needs of the patient.

For a person to give consent, they need to have the mental capacity to understand an explanation, be able to make some form of choice and be able to communicate. Every person with mental capacity has a right to refuse medication if they so wish.

In exceptional circumstances, the law accepts that the giving of medicine to a patient unable to give consent is acceptable provided that the carer is acting in the best interests of the patient and that the care given is of a reasonable standard. Courts have also accepted that doctors may treat patients without their consent if it is seen to be in the best interests of that patient. There are obviously situations in nursing where consent has to be given by those other than the patient – for example parental responsibility, which includes the right to consent on behalf of children.

Where a patient lacks capacity, the law in England does not currently allow others, for example relatives, to give consent on someone’s behalf without legal intervention. When dealing with somebody who does not have the capacity to give consent, professionals must rely on the principle of necessity. This means that treatment should only be given when it is necessary for the patient’s health and well-being. However, relatives and carers are likely to have a detailed understanding of the patient’s circumstances and can offer insights into what their best interests are. Therefore, the nurse should work in partnership with relatives and partners in order to provide the best care for the individual.

Despite the legal and professional debate, you may still come across patients having medicines hidden in their food or drink. Some authors suggest that this is still a common problem and is particularly prevalent in nursing homes. As a student nurse and future professional you should not engage in giving medication covertly to patients unless under exceptional circumstances.

Mental capacity and competence in consent

For those deemed unable to give consent due to lack of mental capacity, prior legal addressing of this situation can give relatives or carers the ability, in law, to act in the best interests power of attorney and power of welfare.

The Mental Capacity Act (2005) is designed to protect those who can’t make decisions for themselves or lack the mental capacity to do so. The Act’s purpose is:

- to allow adults to make as many decisions as they can for themselves;

- to enable adults to make advance decisions about whether they would like future medical treatment;

- to allow adults to appoint, in advance of losing mental capacity, another person to make decisions about personal welfare or property on their behalf at a future date;

- to allow decisions concerning personal welfare or property and affairs to be made in the best interests of adults when they have not made any future plans and cannot make a decision at this time;

- to ensure an NHS body or local authority will appoint an independent mental capacity advocate to support someone who cannot make a decision about serious medical treatment, or about hospital, care home or residential accommodation, when there are no family or friends to be consulted;

- to provide protection against legal liability for carers who have honestly and reasonably sought to act in the person’s best interests;

- to provide clarity and safeguards concerning research in relation to those who lack capacity.

The Act should only be used when the patient is unable to give consent for themselves and has been judged by a medical professional to be lacking in capacity.

When it comes to children and young adults, it is lawful for doctors to provide advice and treatment without parental consent providing certain criteria are met. These criteria, known as the Fraser Guidelines, require the professional to be satisfied that:

- the young person will understand the professional’s advice;

- the young person cannot be persuaded to inform their parents;

- the young person is likely to begin, or to continue having, sexual intercourse with or without contraceptive treatment;

- unless the young person receives contraceptive treatment, their physical or mental health, or both, are likely to suffer;

- the young person’s best interests require them to receive contraceptive advice or treatment with or without parental consent.

Although these criteria specifically refer to contraception, the principles are deemed to apply to other treatments, including abortion. Although the judgement in the House of Lords that produced these criteria referred specifically to doctors, it is considered to apply to other health professionals, including nurses.

Alteration of medicines

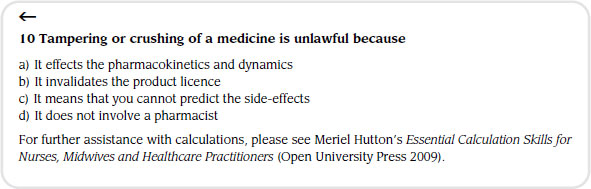

Sadly, few nurses are aware of the pharmacological dangers to the patient and of the legal implications of tampering with drugs.

Drugs only have a licence to be administered in the form in which they are packaged. Therefore, crushing tablets or separating capsules can alter the delivery system. This in turn will affect the pharmacokinetics and dynamics of the medicine resulting in changes in the speed of absorption and therapeutic efficacy.

A nurse who administers a medicine in a way that falls outside the product licence undertakes a degree of liability for any adverse effects caused by maladministration. The nurse can take steps to lessen any personal liability when giving a drug outside its product licence, and one reasonable step is to get the medication prescribed in an alternative form such as a liquid. Some companies specialize in making drugs in liquid form. It is most important, if you see a patient struggling to take medication in tablet or capsule form, that you inform the nurse in charge so that they can speak to the medical staff and get the prescription changed. A further precaution would be to discuss the crushing of the medicine with the pharmacist and get written approval from them that the practice is appropriate.

The issue of tampering with or crushing tablets is a particular dilemma when giving drugs enterally. Enteral feeding refers to the delivery of a complete nutritional feed directly into the stomach, duodenum or jejunum. This type of feeding is usually considered for malnourished patients, or in patients at risk of malnutrition who have a functional GI tract but are unable to maintain an adequate or safe oral intake. In your placement you may come across a variety of methods of giving enteral feeds, for example, nasogastric (NG) or percutaneous endoscopic gastrotomy (PEG).

While tampering with or crushing medication is not a preferred method of administration it is likely that this has to happen when giving drugs enterally, especially if they are not available in liquid form. The nurse may crush or separate capsules as long as the doctor is aware that the drugs are to be given by this route. The doctor could then prescribe the drugs enterally, therefore making administration lawful. The problems of this type of administration becoming unlawful stem from tampering with the medicine but not informing the prescriber of this practice. Some clinical areas have developed separate protocols for enteral administration of medicines. When working in a hospital setting, informing the pharmacy regarding this route of administration is usually enough – they will then facilitate the drugs being available in an appropriate form. You will find that all hospitals have their own medicines policy which usually contains information on crushing or tampering with medicines. You need to become familiar with this document when you are in the placement area.

Reporting of drug errors

In its advice to nurses the NMC highlights the importance of an open culture in practice with regard to the reporting of drug errors. This needs to be fostered in order to encourage the immediate reporting of errors or incidents in the administration of medicines.

Unfortunately, as we work in a more and more litigatious society, drug errors are often not viewed on a case by case basis and disciplinary action is frequently taken against nurses for their mistakes. It could be argued that by taking this approach all that is being achieved is to make nurses reluctant to report such incidents.

As a student nurse, if you make a mistake you are not seen as being culpable in law. However, you need to learn from your mistakes. Therefore, if you make a drug error you may be asked to complete a critical incident analysis of what went on. Using this as a reflective tool you can identify risk management issues that you should have developed in order to minimize the likelihood of the error occurring. The reflective analysis allows you to revisit the situation and to explore your reasons for the course of action you took. This can then be compared with the medicines policy to inform you of the importance of adhering to such important documents.

The adaptation of a no-blame culture is more conducive to the reporting of drug errors. It is a duty of care to the patient that you report any errors to the person in charge of your placement area. If you have seen an error occurring you must report it. This can be very difficult as a student because you want to fit into the team, and you might find yourself in the position of being a ‘whistle-blower’. However, to ignore the incident is a breach of the legal duty of care that you owe to the patient. You would also be failing to follow the standards set in law for the safe administration of medicines.

Controlled drugs

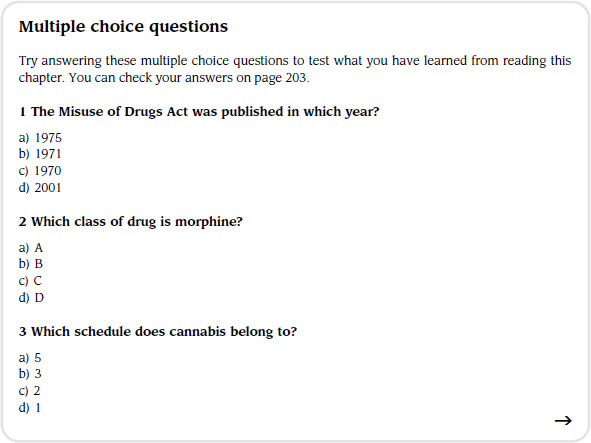

There is much legislation surrounding the prescription, supply, storage and administration of medications. The Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), which supersedes the Dangerous Drug Act (1967), prohibits certain activities in relation to controlled drugs in terms of manufacture, supply and possession. The Act outlines three classes into which the medications it controls fall: class A (e.g. morphine); class B (e.g. codeine) and class C (e.g. buprenorphine).

The Misuse of Drugs Regulations (2001) define the classes of person who are authorized to supply and possess controlled drugs in a professional capacity and under set conditions. The activities governed are import and export, production, supply, possession, prescribing and record-keeping. The Regulations lay out five schedules defining the drugs included (see Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Misuse of Drugs Regulations (2001) five schedules

| Schedule | Drug example | Conditions |

| 1 | Cannabis | Possession and supply prohibited unless under Home Office rule |

| 2 | Morphine | Full controlled drug restriction, register required |

| 3 | Barbiturates | Special prescription requirements |

| 4 | Benzodiazepines | Minimal control, no safe custody, records required |

| 5 | Codeine | Minimal control, no safe custody, record-keeping less stringent than schedule 4 |

You will find that controlled drugs are stored in a particular way, being kept in a separate cupboard. You will often find that this locked cupboard is kept within another locked cupboard. The keys for the controlled drugs cupboard should be kept separate from other keys and the nurse in charge should keep these on his or her person while on duty. When you work on wards in hospital settings you will find that a warning light is placed on the outer cupboard. This indicates to staff whether the cupboard has been left open. No other items should be placed in the controlled drugs cupboard.

When giving a controlled drug you will find that a separate drug register is kept. This keeps an ongoing tally of the amount of drugs used and also lists all the patients that the drugs have been administered to, along with the date and time of administration.

When giving a controlled drug a particular procedure must be followed. This involves two people, one of which must be a qualified nurse or doctor. Some Trusts ask for both nurses to be qualified. Nevertheless, try to get involved in the administration of this category of medicine to gain a full understanding of the procedure and the nurse’s role.

Before administering the controlled drug it must be checked against the amount last entered in the controlled drugs register. Once you have removed the drug from the controlled drug cupboard you must lock the cupboard and prepare the drug for administration. Once the drug has been administered you will have to detail in the controlled drug register the date, time, patient name, amount of drug given, who gave the drug, who witnessed the drug being given, and finally the new stock balance. You may also be involved in checking the stock of controlled drugs at a ward level. This is carried out on a regular basis. Please get yourself involved in this aspect of medicines management.

The ordering of a controlled drug is carried out using a specially designed order book. Controlled drugs can only be ordered by the nurse in charge. The pharmacy will have a copy of that person’s signature which helps them to decide to dispense the drug or not.

Finally, when the controlled drug is delivered to the setting it is usually contained in a locked box and/or delivered by a designated person. The person collecting the drugs from the pharmacy has to sign for them and then someone signs to say they have been received in the clinical area. On receipt, the drugs are checked by two nurses, one of whom must be qualified, and signed for. The newly-ordered drugs are then entered onto the controlled drugs register by both nurses and the tally of drugs is amended accordingly.

Supply and administration of medicines

Traditionally nurses were only involved in administering medication. However, under certain circumstances, they are now involved in supply and administration of medications, usually under a Patient Group Direction (PGD). PGDs are written instructions for the supply or administration of medicines to homogenous groups of patients who require the same treatment. PGDs are used in situations where there is an advantage for patient care without compromising safety. In 1998, the Supply and Administration of Medicines Under Group Protocols report was published (DH 1998). This provided the legal framework for PGDs.

The PGD must be signed by the senior doctor or senior pharmacist involved in developing the direction. The legislation specifies that each PGD must contain the following information (see the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency at www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines):

- the name of the business to which the direction applies;

- the date the direction comes into force and the date it expires;

- a description of the medicine(s) to which the direction applies;

- class of health professional who may supply or administer the medicine;

- signature of a doctor or dentist, as appropriate, and a pharmacist;

- signature by an appropriate organization;

- the clinical condition or situation to which the direction applies;

- a description of those patients excluded from treatment under the direction;

- a description of the circumstances in which further advice should be sought from a doctor (or dentist, as appropriate) and arrangements for referral;

- details of appropriate dosage and maximum total dosage, quantity, pharmaceutical form and strength, route and frequency of administration, and minimum or maximum period over which the medicine should be administered;

- relevant warnings, including potential adverse reactions;

- details of any necessary follow-up action and the circumstances;

- a statement of the records to be kept for audit purposes.

Prescribing law and non-medical prescribing

Traditionally, doctors prescribed, pharmacists dispensed and nurses administered medication. Changes in legislation and the extension of health professionals’ roles has seen this alter in recent years. The idea of prescribing other than by a doctor was first suggested in 1986 following a review of community nursing services, leading to a report by Baroness Julia Cumberlege. In this report, Neighbourhood Nursing: A Focus for Care (DHSS 1986) it was concluded that much of a district nurse’s time was being wasted in obtaining prescriptions for basic dressings and appliances required for patient care. The report also detailed the frustration of some nurses involved in palliative care at not being able to vary timing and dosage of prescribed analgesics as dictated by the patient’s condition.

Further review by Dr June Crown (DH 1989) and her advisory group began the revolution in prescribing practice. Her initial suggestions included:

- ‘initial prescribing’ from a restricted formulary;

- supply within an agreed clinical protocol;

- amendment of timing and dosage of medicines prescribed previously within a patient-specific protocol.

It was a further five years before the first nurse began prescribing. The Medicinal Products: Prescription by Nurses Act was passed in 1992 and nurse prescribing was made legal in 1994 when secondary legislation came into force. Now suitably qualified district nurses were able to prescribe from a limited formulary for specific clinical conditions.

For nurses, however, these changes did not go far enough in addressing their need to prescribe for their patients. They found the formulary restrictive and in some cases were not able to prescribe appropriately for the patients in their care. The Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines (DH 1999) took nurse prescribing further and described two different groups of prescriber: the dependent prescriber, now known as the supplementary prescriber and the independent prescriber, who was a doctor or a dentist.

It was suggested that the dependent prescriber would be able to prescribe certain medications following initial assessment and diagnosis of the patient by the independent prescriber and the development of an agreed clinical management plan (CMP). This allowed nurses access to many more medications as long as they were stated on the CMP.

By now, other allied health professionals were in roles that would benefit from them being able to prescribe. The Health and Social Care Act 2001 (Section 63) allowed the extension of prescribing rights and privileges to certain health care professionals. Changes to the ‘Prescription Only Medicines Order’ and NHS regulations gave suitably qualified nurses and pharmacists supplementary prescribing rights in April 2003 (DH 2005).

This was extended to chiropodists/podiatrists, radiographers, physiotherapists and optometrists in May 2005 and allowed the government to help meet targets set in the NHS Plan (DH 2000). It led to increasing flexibility among multidisciplinary teams by empowering staff and providing efficient and timely access to medicines and an increased patient choice.

Further reviews by the Department of Health (DH) enabled nurses and pharmacists to prescribe independently of a CMP from 2006. These autonomous practitioners are responsible for assessment, diagnosis and treatment of patients for whom their clinical conditions fall within that area of competence. They can prescribe from the whole BNF, with only some restrictions surrounding controlled drugs and non-licensed medications.

Nurse prescribers must have an identified prescribing role within their area of practice, be at least three years post-registration and have successfully completed an approved programme of training. This allows additional registration with the NMC as a nurse prescriber, with the nurse following guidelines and standards laid out by their governing body.

It is envisaged that there will be further developments in the field of nurse prescribing, and although it is not expected that student nurses will become prescribers, they must be aware of who can prescribe to safely participate in medicines management as part of their role.

Recommended further reading

Beckwith, S. and Franklin, P. (2007) Oxford Handbook of Nurse Prescribing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brenner, G.M. and Stevens, C.W. (2006) Pharmacology, 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier.

Clayton, B.D. (2009) Basic Pharmacology for Nurses, 15th edn. St Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Coben, D. and Atere-Roberts, E. (2005) Calculations for Nursing and Healthcare, 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

DH (Department of Health) (1989) Report of the Advisory Group on Nurse Prescribing (Crown Report). London: DoH.

DH (Department of Health) (1998) Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines: A Report on the Supply and Administration of Medicines Under Group Protocols. London: DH.

DH (Department of Health) (1999) A Review of Prescribing, Supply and Administration of Medicines – Final Report (Crown Report 2). London: DH.

DH (Department of Health) (2000) NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. London: DH.

DH (Department of Health) (2005) Supplementary Prescribing by Nurses, Pharmacists, Chiropodists/Podiatrists, Physiotherapists and Radiographers within the NHS in England: a Guide for Implementation. London: DH.

DHSS (Department of Health and Social Security) (1986) Neighbourhood Nursing: A Focus for Care (Cumberlege Report). London: HMSO.

Downie, G., Mackenzie, J. and Williams, A. (2007) Pharmacology and Medicines Management for Nurses, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Gatford, J.D. and Phillips, N. (2006) Nursing Calculations, 7th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Karch, A.M. (2008) Focus on Nursing Pharmacology, 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Lapham, R. and Agar, H. (2003) Drug Calculations for Nurses: A Step-by-step Approach, 2nd edn. London: Arnold.

NHS UK (2005) Managing someone’s legal affairs, www.nhs.uk/CarersDirect/moneyandlegal/legal/Pages/MentalCapacityAct.aspx.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council) (2008) Standards for Medicines Management. London: NMC.

NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council) (2008) Code of Professional Conduct. London: NMC.

Simonson, T., Aarbakke, J., Kay, I., Coleman, I., Sinnott, P. and Lyssa, R. (2006) Illustrated Pharmacology for Nurses. London: Hodder Arnold.

Trounce, J. (2000) Clinical Pharmacology for Nurses, 16th edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>