CHAPTER 83 Leg

This chapter describes the shafts of the tibia and fibula, the soft tissues that surround them and the interosseous membrane between them. The superior (proximal) and inferior (distal) tibiofibular joints are described in Chapters 82 and 84 respectively.

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

The cutaneous arterial supply is derived from branches of the popliteal, anterior tibial, posterior tibial and fibular vessels (see Fig. 79.5). Multiple fasciocutaneous perforators from each vessel pass along intermuscular septa to reach the skin; musculocutaneous perforators traverse muscles before reaching the skin. In some areas there is an additional direct cutaneous supply from vessels that accompany cutaneous nerves, e.g. the descending genicular artery (saphenous artery) and superficial sural arteries. Fasciocutaneous and direct cutaneous branches have a longitudinal orientation in the skin, whereas the musculocutaneous branches are more radially oriented. For further details consult Cormack & Lamberty (1994).

SOFT TISSUE

Deep fascia

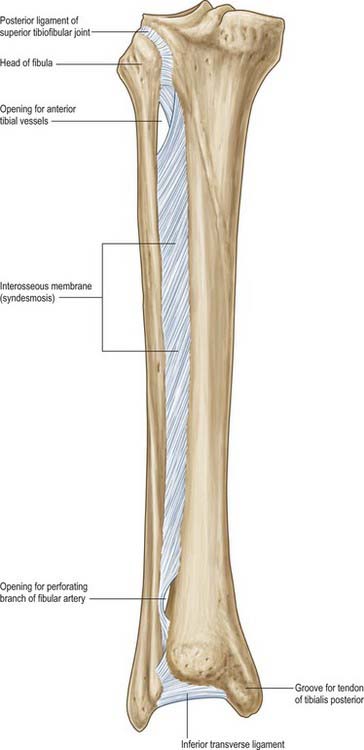

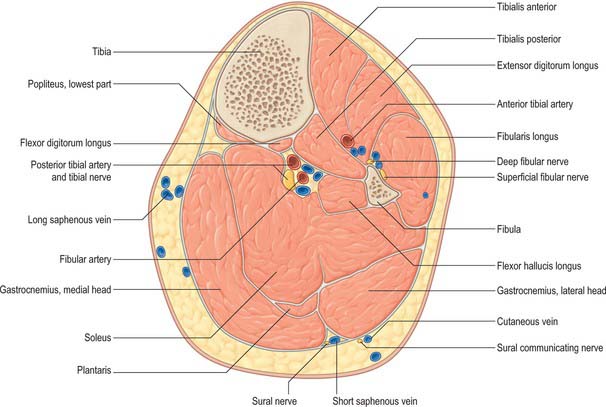

Interosseous membrane

The interosseous membrane connects the interosseous borders of the tibia and fibula (Fig. 83.1). It is interposed between the anterior and posterior groups of crural muscles; some members of each group are attached to the corresponding surface of the interosseous membrane. The anterior tibial artery passes forwards through a large oval opening near the proximal end of the membrane, and the perforating branch of the fibular artery pierces it distally. Its fibres are predominantly oblique and most descend laterally; those which descend medially include a bundle at the proximal border of the proximal opening. The membrane is continuous distally with the interosseous ligament of the distal tibiofibular joint. Tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, extensor hallucis longus, fibularis tertius, the anterior tibial vessels and deep fibular nerve are all anterior to the membrane, and tibialis posterior and flexor hallucis longus are posterior.

Trauma and soft tissues of the leg

The relative paucity of soft tissue in the shin region and the subcutaneous position of the medial surface of the tibia means that even trivial soft tissue injury may lead to serious problems such as ulceration and osteomyelitis. In the elderly these soft tissues are often especially thin and unhealthy, reflecting the effects of ageing and venous stasis (see below). Tibial fractures are common in the young and, partly as a result of poor soft tissue coverage, they are often open injuries. Diminished blood supply to the bone, caused by traumatic stripping of attached soft tissues, and the risk of contamination add greatly to the risk of non-union and infection of the fracture. Healing of fractures at the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the tibia is compromised by the relatively poor blood supply to this region.

BONE

TIBIA

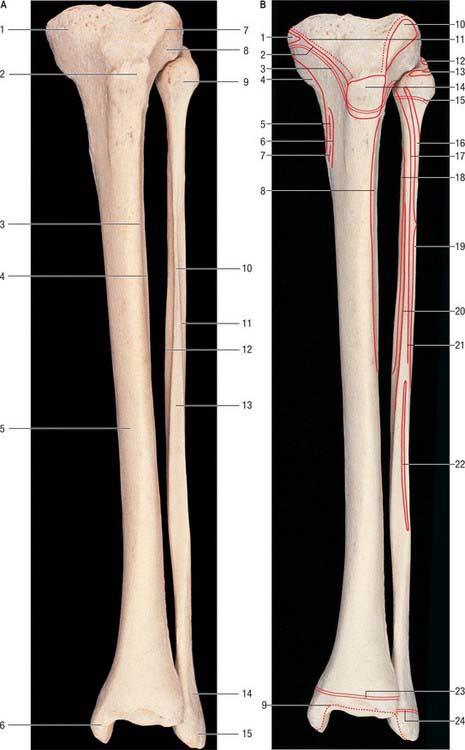

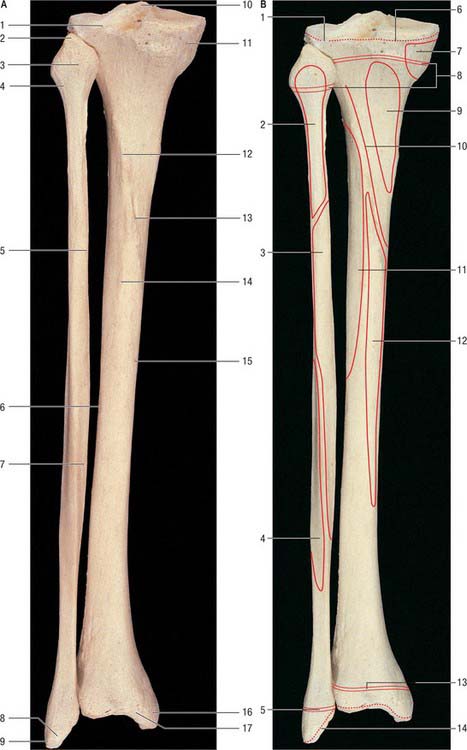

The tibia lies medial to the fibula and is exceeded in length only by the femur (Figs 83.2, 83.3). Its shaft is triangular in section and has expanded ends; a strong medial malleolus projects distally from the smaller distal end. The anterior border of the shaft is sharp and curves medially towards the medial malleolus. Together with the medial and lateral borders it defines the three surfaces of the bone. The exact shape and orientation of these surfaces show individual and racial variations.

Proximal end

The anterior condylar surfaces are continuous with a large triangular area whose apex is distal and formed by the tibial tuberosity. The lateral edge is a sharp ridge between the lateral condyle and lateral surface of the shaft. The condyles, their articular surfaces and the intercondylar area are described in Chapter 82.

The tibial tuberosity is the truncated apex of a triangular area where the anterior condylar surfaces merge. It projects only a little, and is divided into a distal rough and a proximal smooth region. The distal region is palpable and is separated from skin by the subcutaneous infrapatellar bursa. A line across the tibial tuberosity marks the distal limit of the proximal tibial growth plate (Fig. 83.2). The patellar tendon is attached to the smooth bone proximal to this, its superficial fibres reaching a rough area distal to the line. The deep infrapatellar bursa and fibroadipose tissue intervene between the bone and tendon proximal to its site of attachment. The latter may be marked distally by a somewhat oblique ridge, onto which the lateral fibres of the patellar tendon are inserted more distally than the medial fibres. (This knowledge is necessary to avoid damaging the tendon when sawing the tibia transversely just above the tibial tuberosity in a lateral to medial direction, e.g. in performing an osteotomy.) In habitual squatters a vertical groove on the anterior surface of the lateral condyle is occupied by the lateral edge of the patellar tendon in full flexion of the knee.

Shaft

The anteromedial surface, between the anterior and medial borders, is broad, smooth and almost entirely subcutaneous. The lateral surface, between the anterior and interosseous borders, is also broad and smooth. It faces laterally in its proximal three-fourths and is transversely concave. Its distal fourth swerves to face anterolaterally, on account of the medial deviation of the anterior and distal interosseous borders. This part of the surface is somewhat convex. The posterior surface, between the interosseous and medial borders, is widest above, where it is crossed distally and medially by an oblique, rough soleal line. A faint vertical line descends from the centre of the soleal line for a short distance before becoming indistinct. A large vascular groove adjoins the end of the line and descends distally into a nutrient foramen. Deep fascia and, proximal to the medial malleolus, the medial end of the superior extensor retinaculum, are attached to the anterior border. Posterior fibres of the medial collateral ligament and slips of semimembranosus and the popliteal fascia are attached to the medial border proximal to the soleal line, and some fibres of soleus and the fascia covering the deep calf muscles are attached distal to the line. The distal medial border runs into the medial lip of a groove for the tendon of tibialis posterior. The interosseous membrane is attached to the lateral border, except at either end of this border. It is indistinct proximally where a large gap in the membrane transmits the anterior tibial vessels. Distally the border is continuous with the anterior margin of the fibular notch, to which the anterior tibiofibular ligament is attached.

Distal end

The slightly expanded distal end of the tibia has anterior, medial, posterior, lateral and distal surfaces. It projects inferomedially as the medial malleolus. The distal end of the tibia, when compared to the proximal end, is laterally rotated (tibial torsion). The torsion begins to develop in utero and progresses throughout childhood and adolescence till skeletal maturity is attained. Tibial torsion is approximately 30° in Caucasian and Asian populations, but is significantly greater in people of African origin (Eckhoff et al 1994). Some of the femoral neck anteversion seen in the newborn may persist in adult females: this causes the femoral shaft and knee to be internally rotated, and the tibia may develop a compensatory external torsion to counteract the tendency of the feet to turn inwards.

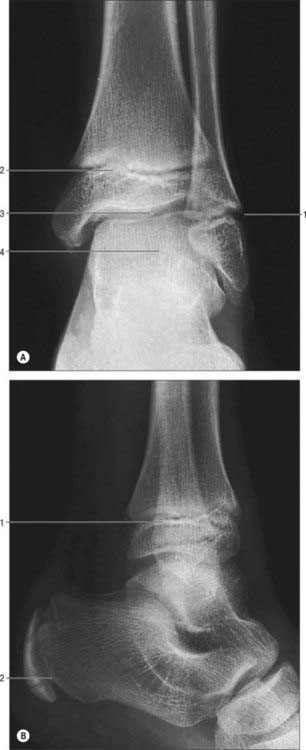

Ossification

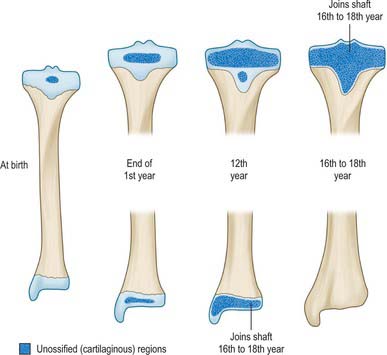

The tibia ossifies from three centres, one in the shaft and one in each epiphysis. Ossification (Figs 83.2, 83.3, 83.4; see Fig. 82.6) begins in midshaft at about the seventh intrauterine week. The proximal epiphysial centre is usually present at birth: at approximately 10 years a thin anterior process from the centre descends to form the smooth part of the tibial tuberosity. A separate centre for the tuberosity may appear at about the twelfth year and soon fuses with the epiphysis. Distal strata of the epiphysial plate are composed of dense collagenous tissue in which the fibres are aligned with the patellar tendon. Exaggerated traction stresses may account for Osgood–Schlatter disease, where fragmentation of the epiphysis of the tuberosity occurs during adolescence and produces a painful swelling in the region of the tuberosity. Healing occurs once the growth plate fuses, leaving a bony protrusion. Prolonged periods of traction with the knee extended, both in children and adolescents, can lead to growth arrest of the anterior part of the proximal epiphysis, which results in bowing of the proximal tibia as the posterior tibia continues to grow. The proximal epiphysis fuses in the 16th year in females and the 18th in males. The distal epiphysial centre appears early in the first year and joins the shaft at about the 15th year in females and the 17th in males. The medial malleolus is an extension from the distal epiphysis and starts to ossify in the seventh year: it may have its own separate ossification centre. In 47% of females and 17% of males, an accessory ossification centre appears at the tip of the medial malleolus which fuses during the eighth year in females and the ninth in males: it should not be confused with an os subtibiale, which is a rare accessory bone found on the posterior aspect of the medial malleolus.

FIBULA

The fibula (Figs 83.2, 83.3) is much more slender than the tibia and is not directly involved in transmission of weight. It has a proximal head, a narrow neck, a long shaft and a distal lateral malleolus. The shaft varies in form, being variably moulded by attached muscles: these variations may be confusing.

Shaft

The lateral surface, between the anterior and posterior borders and associated with the fibular muscles, faces laterally in its proximal three-fourths. The distal quarter spirals posterolaterally to become continuous with the posterior groove of the lateral malleolus. The anteromedial (sometimes simply termed anterior, or medial) surface, between the anterior and interosseous borders, usually faces anteromedially but often directly anteriorly. It is associated with the extensor muscles. Though wide distally, it narrows in its proximal half and may become a mere ridge. The posterior surface, between the interosseous and posterior borders, is the largest and is associated with the flexor muscles. Its proximal two-thirds is divided by a longitudinal medial crest, separated from the interosseous border by a grooved surface that is directed medially. The remaining surface faces posteriorly in its proximal half; its distal half curves onto the medial aspect. Distally this area occupies the fibular notch of the tibia, which is roughened by the attachment of the principal interosseous tibiofibular ligament. The triangular area proximal to the lateral surface of the lateral malleolus is subcutaneous; muscles cover the rest of the shaft.

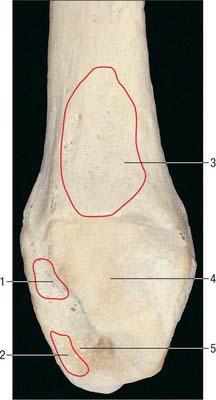

Lateral malleolus

The distal end forms the lateral malleolus which projects distally and posteriorly (Figs 83.2, 83.3, 83.5). Its lateral aspect is subcutaneous while its posterior aspect has a broad groove with a prominent lateral border. Its anterior aspect is rough, round and continuous with the tibial inferior border. The medial surface has a triangular articular facet, vertically convex, its apex distal, which articulates with the lateral talar surface. Behind this facet is a rough malleolar fossa pitted by vascular foramina. The posterior tibiofibular ligament and, more distally, the posterior talofibular ligament, are attached in the fossa. The anterior talofibular ligament is attached to the anterior surface of the lateral malleolus; the calcaneofibular ligament is attached to the notch anterior to its apex. The tendons of fibularis brevis and longus groove its posterior aspect: the latter is superficial and covered by the superior fibular retinaculum.

Muscle attachments

Muscle attachments to the posterior surface, which is divided longitudinally by the medial crest, are complex. Between the crest and interosseous border the posterior surface is concave. Tibialis posterior is attached throughout most (the proximal three-fourths) of this area; an intramuscular tendon may ridge the bone obliquely. Soleus is attached between the crest and the posterior border on the proximal fourth of the posterior surface; its tendinous arch is attached to the surface proximally. Flexor hallucis longus is attached distal to soleus on the posterior surface and almost reaches the distal end of the shaft.

Ossification

The fibula ossifies from three centres, one each for the shaft and the extremities (Fig. 83.6). The process begins in the shaft at about the eighth intrauterine week, in the distal end in the first year, and in the proximal end at about the third year in females and the fourth in males. The distal epiphysis unites with the shaft at about the 15th year in females and the 17th in males, whereas the proximal epiphysis does not unite until about the 17th year in females and the 19th in males‥ An os subfibulare is an occasional and separate entity and lies posterior to the tip of the fibula, whereas the distal fibular apophysis lies anteriorly. An os retinaculi is rarely encountered; if present, it overlies the bursa of the distal fibula within the fibular retinaculum.

MUSCLES

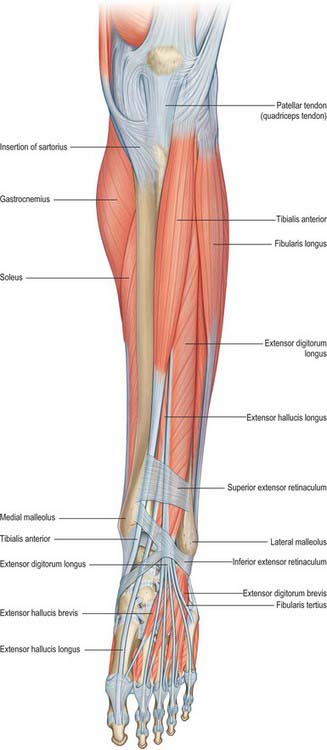

ANTERIOR OR EXTENSOR COMPARTMENT

The anterior compartment contains muscles that dorsiflex the ankle when acting from above (Figs 83.7, 83.8, 83.9). When acting from below they pull the body forward on the fixed foot during walking. Two of the muscles, extensor digitorum longus and extensor hallucis longus, also extend the toes, and two muscles, tibialis anterior and fibularis tertius, have the additional actions of inversion and eversion respectively.

Fig. 83.8 Transverse (axial) section through the left leg, approximately 10 cm distal to the knee joint.

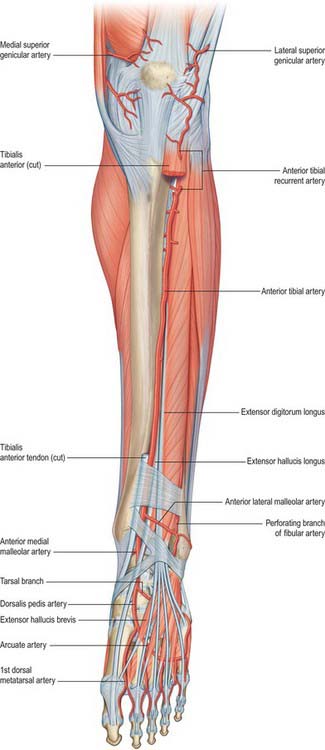

Fig. 83.9 The left anterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries. To expose the anterior tibial artery a large part of tibialis anterior has been excised and extensor hallucis longus is retracted laterally. Compare with Fig. 83.7.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access