Laparoscopic Treatment of Rectal Prolapse

Dennis L. Fowler

Akuezunkpa O. Ude Welcome

Introduction

Rectal prolapse remains a condition for which no consensus exists regarding the diagnostic algorithm, natural history, or course of treatment. Over 100 procedures have been described to treat rectal prolapse, or procidentia. Since the first descriptions of laparoscopic procedures for the treatment of rectal prolapse in the early 1990s until now, a body of literature has accrued that compares open with laparoscopic techniques, laparoscopic techniques with each other, as well as descriptions of hybrid laparoscopic procedures combined with robotic or endoscopic techniques. The benefits of laparoscopic over open surgery—less postoperative pain and narcotic use, shorter length of postoperative ileus, decreased hospital length of stay, improved cosmesis, and high patient satisfaction—have been demonstrated in virtually all major abdominal surgical procedures, including those for rectal prolapse. This chapter shall outline the most common laparoscopic techniques described in the current literature.

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Procidentia has a bimodal incidence and is most frequently seen at the extremes of life. Rectal prolapse in children is primarily mucosal. Unlike procidentia in the pediatric population, adult rectal prolapse is not a self-limiting disease. The more common version is acquired, predominantly affects elderly women, and is often associated with other pelvic floor pathology including uterine and vaginal prolapse, rectocele, and cystocele. Patient complaints include mucous discharge, pain, tenesmus, constipation, and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

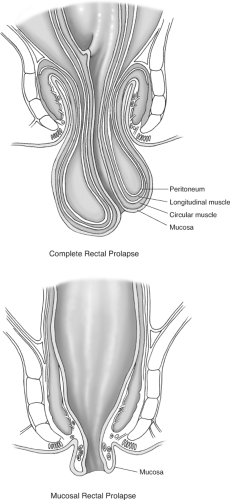

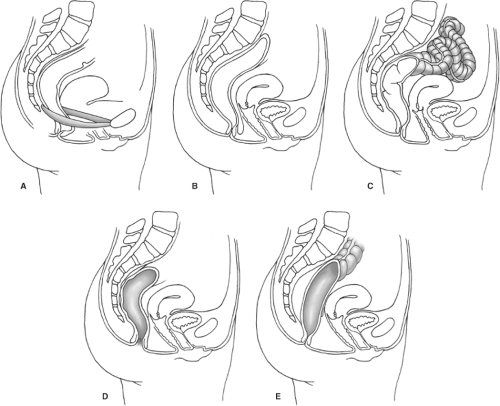

Rectal prolapse has been conceptualized as either a sliding hernia or an intussusception of the rectum. In general, classification systems stratify prolapse according to the layers that form the intussusceptum (full thickness vs. mucosal) and whether the intussuscipiens–intussusceptum complex passes through the anus (complete vs. partial). Complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse is an indication for an anti-prolapse operative repair. False or incomplete (mucosal) prolapse may benefit from a hemorrhoidectomy or banding (Fig. 1). The anatomic abnormalities in patients with rectal prolapse include a redundant sigmoid, an elongated mesorectum with loss of the rectosigmoid angle, atrophy and separation of the levator ani, a patulous anus, and a deep cul-de-sac (Fig. 2).

There are functional abnormalities as well, most commonly constipation and anal

incontinence. In patients with rectal prolapse, the rectum requires smaller volumes of stool to stimulate the urge to defecate. At the same time, the resting pressure of the internal sphincter is decreased but squeeze pressures remain normal. This suggests that the internal sphincter alone is dysfunctional. The combination of a weak internal sphincter and a rectum that is hypersensitive to distension provides a plausible explanation for the high incidence of incontinence in this patient population.

incontinence. In patients with rectal prolapse, the rectum requires smaller volumes of stool to stimulate the urge to defecate. At the same time, the resting pressure of the internal sphincter is decreased but squeeze pressures remain normal. This suggests that the internal sphincter alone is dysfunctional. The combination of a weak internal sphincter and a rectum that is hypersensitive to distension provides a plausible explanation for the high incidence of incontinence in this patient population.

The most critical part of the preoperative evaluation is the patient’s history. Specific questions should address the presence and degree of constipation. This can be evaluated by asking about the number of successful defecations per week, the amount of time spent straining, the duration and quantity of laxative or suppository use, and the need for digitations. The review of systems should gauge the patient’s degree of incontinence using one of several validated scales. The physical examination must include not only a digital rectal examination to assess rectal tone and rule out the presence of a sigmoidocele, a mass, or sphincter defects, but also visual examination of the patient’s anus while he or she strains on the toilet.

Authors differ on the number and type of preoperative imaging and functional studies that are required prior to operating. Most tests are ordered based on the patient’s constellation of symptoms. However, a screening colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy with barium enema is imperative to evaluate the colon for other abnormalities. If no protrusion of rectum is seen during the physical examination, defecography may be needed to diagnose a more proximal intussusception. In addition to these studies, some authors obtain colonic transit studies to evaluate for slow transit, electromyography and measurement of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency to rule out neurologic problems and anal manometry to measure sphincter pressures. Advanced imaging modalities such as dynamic, three-dimensional computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging have also been used to diagnose pelvic floor disorders including rectal prolapse.

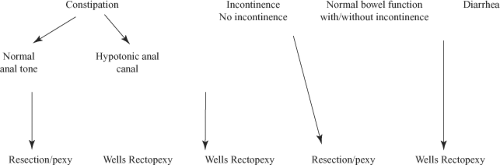

It is imperative to differentiate patients with morphologic disorders (such as a rectocele or sigmoidocele) from those with functional disorders such as anismus or pudendal nerve neuropathy. These results may impact the decision to operate, the choice of operation, and the surgeon’s ability to offer the patient prognostic information regarding the recovery of continence and the resolution of his or her constipation. Different reports have presented contradictory results regarding the degree of correlation between these test results and patients’ pre- and postoperative symptoms. As examples, patients with slow transit will benefit from a resection; while those with very low

preoperative resting pressures should be counseled that they may never have restoration of continence.

preoperative resting pressures should be counseled that they may never have restoration of continence.

The goals of surgery are twofold: to correct the anatomic abnormalities associated with prolapse and to provide the patient with functional improvement of his or her symptoms. As many as 75% of patients with rectal prolapse suffer from anal incontinence, and 25% to 50% report constipation. Any assessment of the success of an operation would be incomplete if it did not document the efficacy of the procedure in resolving these symptoms. To that end, all procedures discussed today involve one or more of the following steps: resection of redundant sigmoid colon, fixation of the rectum to the sacrum, and a reconstruction of the pelvic floor. The various nonlaparoscopic approaches to rectal prolapse have been described in earlier chapters. In patients whose medical conditions preclude the administration of general anesthesia, the perineal procedures provide adequate relief of symptoms, but are associated with a shorter duration of relief and a higher recurrence rate. The laparoscopic approaches that will be described mimic the abdominal approaches.

The laparoscopic surgical options include rectopexy with or without mesh, sigmoid resection alone, or a combination of the two. No one operation is suitable for all prolapse patients; therefore, the operation must be tailored to the patient and his or her individual symptoms. A resection with rectopexy is indicated in patients who have sigmoid diverticular disease, a sigmoidocele, a redundant sigmoid colon, slow transit time, and/or constipation. A rectopexy alone is relatively contraindicated in patients with constipation due to the high rates of persistence or worsening of constipation following this procedure. An absolute contraindication to a laparoscopic repair is the patient’s inability to tolerate general anesthesia, while relative contraindications include prior abdominal surgery and irreducible prolapse (Fig. 3).

Preoperative Preparation

Patients start a clear liquid diet 2 days before surgery. On the day prior to surgery, the patient should take two doses of an over-the-counter phosphosoda preparation. If antibiotic prophylaxis is desired, the patient should take 1 g metronidazole and 1 g neomycin at 2 p.m., 3 p.m., and 11 p.m. The patient is NPO the night before surgery. Preoperative parenteral antibiotics (a third-generation cephalosporin or a fluoroquinolone and metronidazole for patients with penicillin allergies) are given prior to the induction of general anesthesia. The patient is positioned supine on a beanbag atop a split-leg table and sequential venous compression stockings are placed on both lower extremities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree