Matthew M. Hutter

DEFINITION

■ Sleeve gastrectomy or partial vertical gastrectomy is defined as the creation of tubular, sleeve-shaped, lesser curve–based stomach by resection of the greater curvature of the gastric body and fundus.

■ Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has been an increasingly popular procedure due to its relative technical simplicity and excellent safety and efficacy profile. With an increased number of insurers now covering the sleeve gastrectomy, the number of LSG performed in the United States has grown rapidly in the last several years.

■ LSG was initially performed as the first stage of the biliopancreatic diversion–duodenal switch procedure. However, beginning in 2008, LSG has been performed as a stand-alone bariatric operation, and short- and medium-term follow-up have documented its safety and efficacy.

■ In 2010, a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code was assigned to the procedure and, more recently, the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery has issued a statement with 3- and 5-year data and robust experience acknowledging LSG as an approved primary bariatric procedure.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ A complete history and physical examination should be obtained, with particular attention given to history or identification of metabolic disorders such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and fatty liver disease; cardiovascular disease; obstructive sleep apnea; venous thromboembolism as well as a history of previous abdominal operations.

■ Per National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus guidelines, bariatric surgery is indicated for patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 or a BMI greater than 35 with obesity-associated comorbidities. Insurers and payers, though, may have other stipulations.

■ A detailed nutritional history, including prior attempts at weight loss through dietary, exercise, and medical programs, and psychologic/psychiatric history should be obtained.

■ Multidisciplinary evaluation with registered dietitians, psychologists, and medical physicians is critical prior to consideration for any bariatric surgery.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ In the absence of history or physical findings suggestive of upper gastrointestinal (GI) pathology, preprocedural imaging is not mandatory.

■ However, symptoms such as dysphagia, early satiety, or odynophagia should prompt further radiologic or endoscopic evaluation.

■ In our practice, some find a preoperative barium swallow helpful to rule out gross esophageal motility disorder; assess for hiatal hernias; and exclude mass lesions, stricture, diverticula, and other anatomic abnormalities. Others get a swallow study only if the history and symptoms raise any concerns.

■ Subsequent upper endoscopy can then be selectively used to follow up any concerning findings from the swallow study.

■ When esophageal dysmotility is suspected based on history or swallow study, preoperative esophageal manometry is obtained.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Preoperative laboratory, pulmonary, and cardiac evaluation are performed as indicated by patient history, age, and comorbidities as with other major abdominal surgery.

■ Patients should be encouraged to lose as much weight as possible leading up to surgery. We place our patients on a low caloric diet 2 to 3 weeks before surgery in order to decrease the volume and rigidity of the left lobe of the liver, facilitate laparoscopic exposure, and allow for a less technically demanding and safer operation.

■ Appropriate antibiotic and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis should be administered in a timely fashion.

Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine or in the split-leg position according to the surgeon’s preference. Specialized bariatric beds are available to accommodate the super obese and allow for ergonomic positioning of the patient. The arms and legs should be well secured along with a footboard to allow steep reverse Trendelenburg to facilitate visualization of the left upper quadrant intraoperatively. An orogastric tube should be placed to decompress the stomach after endotracheal intubation.

TECHNIQUES

PORT PLACEMENT

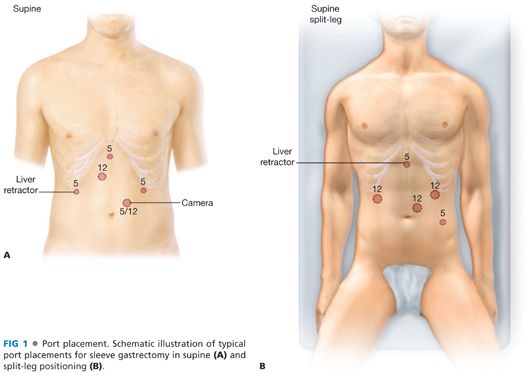

■ Initial peritoneal access is obtained using the surgeon’s preferred method. Pneumoperitoneum is created, and subsequent ports are placed under direct visualization. Many geometric arrangements for port placement will allow adequate exposure for the operation. In general, five ports in the upper abdomen will allow adequate access and visualization for the operation. These will usually include two working ports for the operating surgeon and ports for the camera, liver retractor, and assistant. At least one 12- or 15-mm trocar is required to allow introduction of a stapler. Two example diagrams of port placement are shown in FIG 1.

MOBILIZATION OF THE STOMACH

■ After exploration of the peritoneal cavity, the patient is placed into steep reverse Trendelenburg position to drop away the intestines and omentum, and a liver retractor is placed to expose the stomach and hiatus.

■ The pylorus is identified and the distal margin of the sleeve is measured within 2 to 6 cm proximal to the pylorus (FIG 2A,B). The greater curvature of the stomach is mobilized by transecting the gastrocolic ligament and short gastric vessels. An ultrasonic or bipolar vessel-sealing device speeds this dissection (FIG 3). Proximally, the vessels are divided up to the highest short gastric, a reliable landmark which often dives posteriorly toward the pancreas (FIG 4). We find that complete mobilization of the angle of His from the left crus of the diaphragm and freeing of any lesser sac adhesions to the pancreas or posterior gastric space facilitates subsequent formation of the gastric sleeve. These adhesions are often avascular and can be taken sharply. Complete mobilization to allow adequate resection of the fundus is believed to be a critical step of sleeve gastrectomy.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree