Laparoscopic Pancreatic Debridement

O. Joe Hines

Kathleen Hertzer

DEFINITION

Laparoscopic pancreatic debridement is a minimally invasive technique for pancreatic resection and is indicated in the case of infected pancreatic necrosis as a result of acute pancreatitis. Additional options for pancreatic necrosectomy include laparotomy as well as other minimally invasive methods such as percutaneous catheter drainage and endoscopic drainage. Methods of laparoscopic debridement will be the focus of this chapter.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of acute pancreatitis includes biliary colic, peptic ulcer disease, cholecystitis, acute mesenteric ischemia, small bowel obstruction, visceral perforation, vascular catastrophes such as ruptured aortic aneurysm, as well as intraabdominal infection.

In the setting of recent, severe acute pancreatitis, characteristic CT findings and patient history and physical findings are strongly supportive of infected versus sterile pancreatic necrosis, pancreatic abscess, or pancreatic pseudocyst.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Acute pancreatitis has a broad range of clinical symptoms. The majority of cases can be mild and self-limiting; however, about 20% of these patients will develop severe acute pancreatitis and among these patients, approximately 30% to 70% will develop infected necrosis.1

Severe acute pancreatitis is associated with high mortality and morbidity; these patients are at risk for infection, multisystem organ failure, and death.

Secondary infection of pancreatic necrosis occurs by bacterial or fungal translocation through the GI tract or by seeding through transient bacteremia from invasive monitoring in the intensive care setting.

Infection of pancreatic necrosis can occur as early as 10 days after the onset of acute pancreatitis. More typically, infection ensues 3 to 6 weeks after the initial onset of symptoms.

Patient history and physical examination for pancreatitis and pancreatic necrosis include a recent history of acute pancreatitis and continued abdominal pain, chronic low-grade fever, nausea, lethargy, and inability to eat. Those patients with infected pancreatic necrosis will show signs of intraabdominal infection including tachycardia, hypotension, fever, and deteriorating organ function.

Conservative management is recommended in the case of sterile necrosis. Surgical management can be considered in symptomatic sterile necrosis; not infrequently, occult infection proves to be present. In the setting of clearly infected pancreatic necrosis, debridement or drainage is the preferred method of treatment.

Methods for debridement include open necrosectomy and multiple minimally invasive modalities, including laparoscopic debridement. Minimally invasive necrosectomy is technically achievable and although there is evidence that a step up minimally invasive technique (percutaneous drainage with or without following retroperitoneal necrosectomy) may reduce morbidity and mortality amongst patients with infected necrotizing pancreatitis, it is unclear if minimally invasive techniques are cost effective.2,3

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs are nonspecific. Ultrasound (US) may show a diffusely enlarged, hypoechoic pancreas and can be important in identification of the etiology of pancreatitis (e.g., gallstones).

Appropriate imaging for acute pancreatitis includes contrastenhanced computed tomography (CT) scan when complications are clinically suspected. Complications of pancreatitis evolve with time and impending necrosis may not be appreciated on CT imaging obtained within the first 24 to 48 hours of symptoms. CT imaging in the case of mild acute pancreatitis will show pancreatic enlargement, edema, peripancreatic fat stranding as well as effacement of the normal contours of the organ.

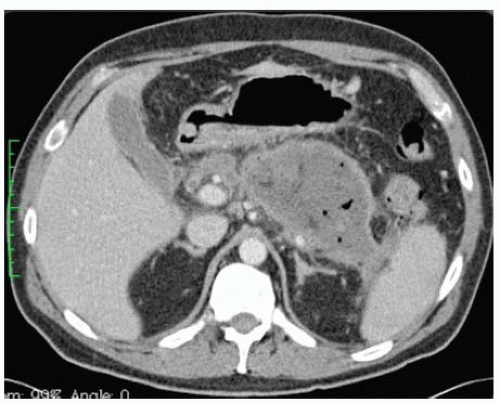

In the setting of pancreatic necrosis, IV contrast can help delineate areas of poor perfusion as well as the extent of necrosis and can be used to predict the severity of disease. Visualization of air bubbles within necrotic tissue is diagnostic of infection (FIG 1).

Table 1: Computed Tomography Grading System of Acute Pancreatitis

Grade

Findings

Score

A

Normal pancreas

0

B

Focal or diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, irregular organ contour

1

C

Peripancreatic inflammation with intrinsic pancreatic abnormalities

2

D

Fluid collections either intrapancreatic or extrapancreatic

3

E

Two or more large collections of gas in the pancreas or retroperitoneum

4

The grading of severity of pancreatitis can be classified into five categories (Table 1) and a CT severity index can be calculated based on the grading of unenhanced CT findings and the percentage of necrosis demonstrated on contrastenhanced CT (Table 2). The CT severity index is the sum of the unenhanced CT score and the necrosis score where the maximum is 10 and greater than or equal to 6 indicates severe disease.4

If infected pancreatic necrosis is suspected, the diagnosis is confirmed with culture results from CT-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) or from specimens collected during necrosectomy.

FNA and culture should be obtained in patients who show clinical features of sepsis or those with a deteriorating clinical course 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of disease.

Table 2: Necrosis Score

% Necrosis

Score

0

0

<33

2

33-50

4

≥50

6

Commonly, the Atlanta classification is used to divide acute pancreatitis into mild and severe categories. The criteria for severe acute pancreatitis include the following: a Ranson’s score of 3 or greater, an APACHE II score of 8 or greater within the first 48 hours, organ failure, or local complications (necrosis, abscess, or pseudocyst involving the pancreas). Other predictors of disease severity within the first 24 hours of hospitalization include a C-reactive protein of greater than 120 mg/dL, procalcitonin greater than 1.8 ng/mL, and a hematocrit greater than 44.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree