■ Upper endoscopy evaluates for esophageal injury and Barrett’s esophagus secondary to GERD while excluding malignant pathology with biopsies as necessary. Endoscopy allows the surgeon to evaluate for the presence of a hiatal hernia as well as to visually inspect the LES.

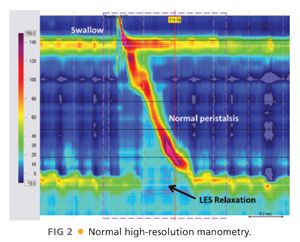

■ Esophageal manometry (FIG 2) assesses LES pressure and relaxation as well as esophageal motility. Patients with esophageal motility disorders can easily be mislabeled as having GERD based on symptoms. Understanding a patient’s esophageal motility is necessary to plan successful antireflux surgery.

■ Esophagogram evaluates gastroesophageal anatomy and abnormalities such as hernia, stricture, diverticula, motility, or tumors.

■ Ancillary tests that may also be useful include laryngoscopy, gastric emptying scintigraphy, and impedance testing.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ There is rarely an absolute indication for antireflux surgery in a patient with GERD. Medical management, including acid suppression therapy and lifestyle modifications (e.g., dietary changes, weight loss), is usually sufficient to manage most patients’ GERD symptoms. Many factors must be considered in making the decision to proceed with antireflux surgery. These include symptom severity, symptom control with medical therapy, complications of GERD (e.g., severe esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, chronic respiratory complaints), and the generalized health of the patient.

■ Patients best suited for an antireflux procedure are those with documented and confirmed GERD for whom medical and lifestyle changes are not providing adequate quality-of-life improvement. When the quality-of-life impairment justifies accepting the risk of surgery, antireflux surgery is indicated.

Preoperative Planning

Positioning

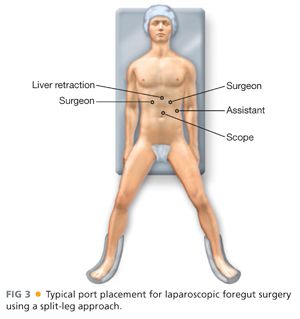

■ Patient can be positioned in either modified lithotomy position or supine depending on surgeon preference. Lithotomy position requires more time and equipment and has more risks of nerve injury. However, lithotomy position provides superior ergonomics for the surgeon. Both arms should be tucked to not interfere with instrumentation and the patient should be adequately stabilized on the bed to safely accommodate steep reverse Trendelenburg (which allows organs to naturally fall away from the hiatus and left upper quadrant).

■ Standard trocar placement includes three working trocars, a fourth trocar for the camera, and a fifth for liver retraction. FIG 3 illustrates standard trocar placement, surgeon, and assistant positioning.

■ Elevation of the left lateral lobe of the liver is necessary to visualize the esophageal hiatus. This is most commonly accomplished with a retraction device of the surgeon’s choice.

TECHNIQUES

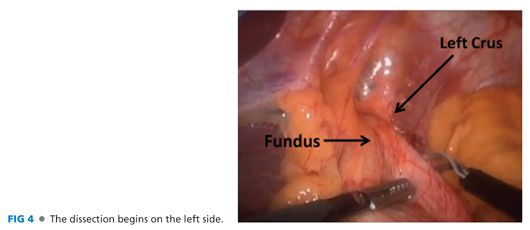

TAKE DOWN THE LEFT PHRENOGASTRIC LIGAMENT

■ After obtaining laparoscopic access to the abdomen and placement of trocars and the liver retractor, the phrenogastric ligament is divided, exposing the left crus. This is most easily accomplished by traction on the gastroesophageal (GE) junction fat pad and the gastric fundus (FIG 4). Many surgeons start on the right side by dividing the gastrohepatic ligament and right phrenoesophageal ligament. We have found that it is safer to first approach the hiatus from the left, which provides better visualization, but both approaches are acceptable.

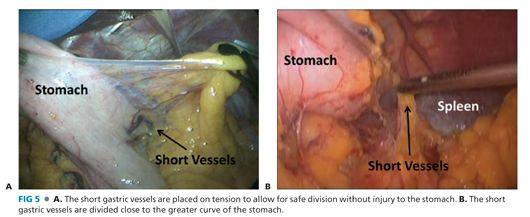

LIGATE AND DIVIDE THE SHORT GASTRIC VESSELS

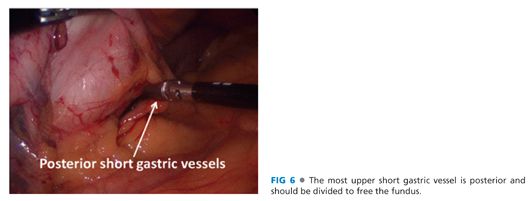

■ The short gastric vessels between the greater curvature of the stomach and the spleen are ligated and divided from the gastric midbody to the angle of His (FIG 5). The most superior short gastric vessels can be difficult to expose. Care must be taken to avoid capsule tears to the spleen during this maneuver. More posterior short gastric vessels and retroperitoneal adhesions must also be released to facilitate full mobilization of the fundus (FIG 6).

EXPOSE THE ENTIRE LEFT CRUS

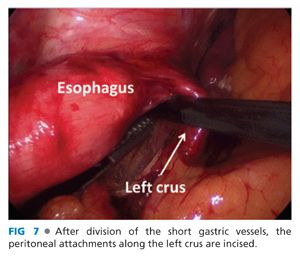

■ The left phrenoesophageal membrane is opened along its length (FIG 7).

OPEN GASTROHEPATIC LIGAMENT

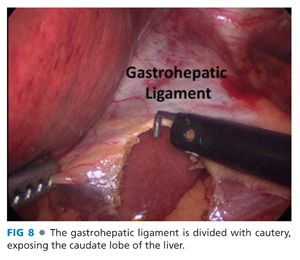

■ The right crus is exposed by opening the gastrohepatic ligament widely, taking care to avoid injury to nerve of Latarjet (FIG 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree