Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair takes a totally different approach from open repair. It is most nearly analogous to a preperitoneal open repair, sometimes termed the Nyhus repair, performed with mesh. The logic is similar to that employed during laparoscopic ventral herniorrhaphy: Because the problem is a weakness in the transversalis fascia (or a persistently patent processus vaginalis), approach the defect from inside. Peritoneum is stripped from the region, and the defect is repaired with a large sheet of prosthetic mesh. Intra-abdominal pressure holds the mesh buttressed against the muscular and aponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall, which are not dissected. Tacks are placed to secure the mesh in place. The anatomy that is stressed for this repair is very different than that stressed in Chapter 115. There is little emphasis on the muscular and aponeurotic layers of the abdominal wall, because these layers are not encountered. Rather, avoiding complications during these procedures requires intimate knowledge of the anatomy of crucial nerves and blood vessels that must be avoided when the mesh is secured. Major complications of the procedure include vascular injury and neurapraxia. The procedure may be done transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneal (TEP). In this chapter, the transabdominal approach is shown first, followed by the modification employed for TEP.

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified laparoscopic inguinal or femoral hernia repair as “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedures.

STEPS IN PROCEDURE

Transabdominal Preperitoneal (TAPP) Approach

Supine position

Trocars at umbilicus and left and right paraumbilical

Abdominal exploration

Confirm presence of hernia defect or defects

Incise peritoneum from median umbilical ligament to anterosuperior iliac spine, approximately 2 cm cephalad to hernia

Develop flaps and reduce sac

Tailor large piece of mesh and pass into abdomen

Secure mesh with staples or tacks along superior edge of mesh

Close peritoneum over mesh

Close trocar sites in usual fashion

Total Extraperitoneal Repair (TEP)

Initial entry into preperitoneal space via open technique

Bluntly dissect preperitoneal fat from fascia

Use dissecting balloon to develop the space

Place additional trocars

Separate sac from underlying structures; ligate large indirect sac if necessary

Place mesh as noted above

Close trocar sites in usual fashion

HALLMARK ANATOMIC COMPLICATIONS

Injury to lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Injury to anterior femoral cutaneous nerve

Injury to femoral nerve

Injury to genitofemoral nerve (femoral or genital branches)

Injury to external iliac artery or vein

Injury to aberrant obturator arteries

Injury to bladder (if prior surgery in the preperitoneal space)

LIST OF STRUCTURES

Peritoneum

Transversalis fascia

Patent processus vaginalis

Ductus deferens

Seminal vesicles

Round ligament of uterus

Bladder

Deep (internal) inguinal ring

Medial Umbilical Ligament (Fold)

Urachus

Median umbilical ligaments (folds)

Obliterated umbilical artery

Lateral Umbilical Ligaments (Folds)

Inferior epigastric artery and vein

Supravesical fossa

Medial umbilical fossa

Lateral umbilical fossa

Hesselbach triangle

Iliopubic tract

Femoral canal

Cooper ligament

Conjoint tendon

Arch of aponeurosis of transversus abdominis

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

Anterior femoral cutaneous nerve

Femoral nerve

Genitofemoral nerve

Femoral branch

Genital branch

Ilioinguinal nerve

Iliohypogastric nerve

External iliac artery and vein

Femoral artery and vein

Internal iliac artery and vein

Obturator Artery

Aberrant obturator artery

Prevesical space (of Retzius)

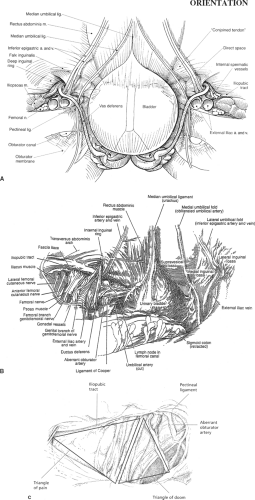

The muscular and aponeurotic structures of the anterior abdominal wall appear different when viewed from inside with the peritoneum removed (Fig. 116.1A). Note how the ductus (or vas) deferens enters through the deep inguinal ring and then passes inferiorly and medially to join the seminal vesicles in the region of the base of the bladder. The internal spermatic vessels pass from lateral to medial and ascend to pass through the deep inguinal ring. The inferior epigastric vessels ascend and pass medially, defining the lateral border of Hesselbach triangle. The medial umbilical ligaments, the obliterated remnants of the umbilical arteries, form useful visual landmarks. The median umbilical landmark is rarely seen. Figure 116.1B shows peritoneum intact on the right side, demonstrating the peritoneal folds and visual landmarks with peritoneum intact. On the left side, the peritoneum has been removed to reveal underlying structures of significance. Note the iliopubic tract, the femoral canal, Cooper ligament, and the arch of the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis. Contrast this view with the anterior and posterior views shown in Chapter 115, Figure 115.1.

Multiple nerves and vessels, most never encountered during open inguinal or femoral herniorrhaphy, are at risk during laparoscopic repair. Nerves include the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, the anterior femoral cutaneous nerve, the femoral nerve, the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. The vascular structures at risk include the external iliac artery and vein and aberrant obturator arteries. The latter, also termed the “artery of death,” is a potential pitfall when a femoral hernia is repaired from above (see Figure 115.9 in Chapter 115).

Two triangles, which lie together to form a rough trapezoid, encompass the majority of these structures and form a useful mnemonic device (Fig. 116.1C). The “triangle of pain” is bounded by the iliopubic tract superiorly, the testicular vessels medially, and the cut edge of the peritoneum inferiorly. It contains most of the nerves previously mentioned. The “triangle of doom,” bounded by the testicular vessels laterally, the ductus deferens medially, and the cut peritoneal edge inferiorly, contains the vessels. Extreme care must be exercised while dissecting in these triangles, and no staples or other fixation devices should be placed in these regions.

TAPP—Orientation and Initial View of Male and Female Pelvis (Fig. 116.2)

Technical Points

Position the patient supine. Place three ports as shown (Fig. 116.2A). Use an angled (30- or 45-degree) laparoscope for better visualization of the inguinal region. Note that in the male, the ductus deferens and inferior spermatic vessels form the apex of a triangle that points to the internal inguinal ring (Fig. 116.2B). Normally, the peritoneum over this region is smooth, or, at most, a tiny dimple or crescentic fold will be seen at the internal ring. In the female, the round ligament is seen to terminate in the internal ring (Fig. 116.2C). Confirm the presence of a hernia or of multiple defects by noting outpouchings in the peritoneum either medial (direct) or lateral (indirect) to the inferior epigastric vessels (Fig. 116.2D, E).

Anatomic Points

As the parietal peritoneum covers the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall and pelvis, underlying structures tent it up, creating five peritoneal folds. These form visual landmarks useful to the laparoscopic surgeon.

In the midline, the remnant of the obliterated urachus links the umbilicus with the dome of the bladder. Although this median umbilical fold is shown in parts A and B of the Figure 116.1, it is rarely actually visible to the laparoscopic surgeon, perhaps because it is so close to the umbilically placed laparoscope. The space above the bladder is termed the supravesical fossa.

Figure 116.1 Laparoscopic view of pelvis and inguinal region. A: Peritoneum stripped to reveal underlying structures. B: Peritoneum intact on right side, stripped on left. C: Triangles of doom and pain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|