7 Kidney and urinary tract disease

Renal medicine ranges from the management of common conditions (e.g. urinary tract infection) to the use of complex technology to replace renal function (e.g. dialysis and transplantation). There are close links with the surgical specialties of urology and transplantation. This chapter describes the common disorders of the kidneys and urinary tract which are encountered in everyday practice, as well as giving an overview of the highly specialised field of renal replacement therapy.

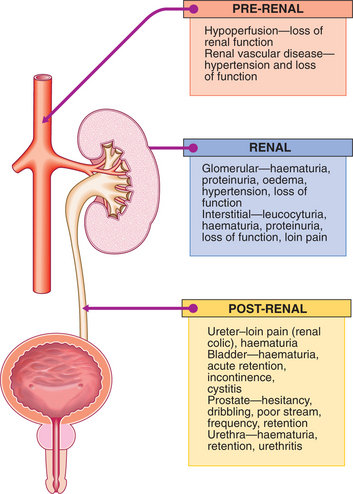

PRESENTING PROBLEMS

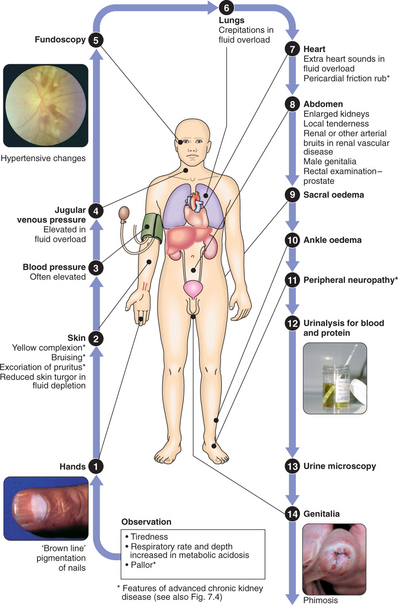

CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF THE KIDNEY AND URINARY TRACT

In hospital, E. coli still predominates, but Klebsiella or streptococci are more common than in the community. Certain strains of E. coli have a particular propensity to invade the urinary tract.

Clinical assessment

Typical features of cystitis and urethritis include:

Systemic symptoms are usually slight or absent. However, infection in the lower urinary tract can spread; prominent systemic symptoms with fever and loin pain suggest the presence of acute pyelonephritis (p. 167) and may be an indication for hospitalisation.

The differential diagnosis includes urethritis due to an STD (p. 130) or Reiter’s syndrome.

Investigations

An approach to investigation is shown in Box 7.1.

7.1 INVESTIGATION OF PATIENTS WITH UTI ![]()

Management

PERSISTENT OR RECURRENT UTI

Treatment failure, with persistence of organisms on repeat culture, suggests an underlying cause, which should be investigated (Box 7.1) and treated. Reinfection with a different organism, or with the same organism after an interval, may also occur. In women, recurrent infections are common and further investigation is only justified if infections are severe or frequent (>2/yr).

If the cause cannot be removed, suppressive antibiotic therapy can be used to prevent recurrence and reduce the risk of septicaemia and renal damage. Regular urine culture and a regimen of two or three antibiotics in sequence, rotating every 6 mths, are used to reduce the emergence of resistant organisms. Other simple measures may help to prevent recurrence (Box 7.2).

LOIN PAIN

ACUTE PYELONEPHRITIS

Clinical assessment

RENAL COLIC

Urinary calculi: These vary in frequency around the world, probably as a consequence of dietary and environmental factors, but genetic factors may also contribute. In Europe, 80% of renal stones contain crystals of calcium salts, about 15% contain magnesium ammonium phosphate, and small numbers of pure cystine or uric acid stones are found. In developing countries, bladder stones are common, particularly in children. In developed countries, the incidence of childhood bladder stones is low; renal stones in adults are more common. Several risk factors for renal stone formation are known (Box 7.3); however, in developed countries, most calculi occur in healthy young men with no clear predisposing cause.

Clinical assessment of impacted ureteric stone

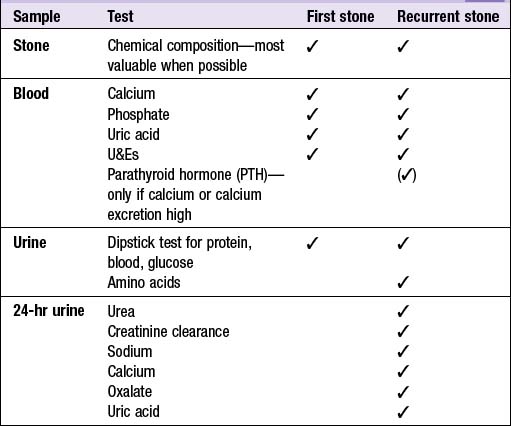

Investigations

Patients with a first renal stone should have a minimum set of investigations (Box 7.4); more detailed investigation is reserved for those with recurrent or multiple stones, or those with complicated or unexpected presentations. Since most stones pass spontaneously, urine should be sieved for a few days after an episode of colic to collect the calculus for chemical analysis.

Management

Around 90% of stones <4 mm in diameter will pass spontaneously, but only 10% of stones of >6 mm will pass and these may require active intervention. Immediate action is required if there is anuria or if severe infection occurs in the stagnant urine proximal to the stone (pyonephrosis). Most stones can be fragmented by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in which shock waves generated outside the body are focused on the stone, breaking it into small pieces which can pass easily down the ureter. This requires free drainage of the distal urinary tract.

EXCESSIVE MICTURITION

POLYURIA

Causes of an inappropriately high urine volume (>3 litres/day) are shown in Box 7.5. In the assessment of polyuria accurate documentation of intake is essential.

URINARY INCONTINENCE

Urinary incontinence is defined as any involuntary leakage of urine. Urinary tract pathology causing incontinence is described below. It may also occur with a normal urinary tract, e.g. in association with poor cognition or poor mobility, or transiently during an acute illness or hospitalisation, especially in older people. Diuretics (medication, alcohol or caffeine) may worsen incontinence.

Clinical assessment and investigations

Incontinence syndromes

Overflow incontinence: This occurs when the bladder becomes chronically over-distended. It is most common in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia or bladder neck obstruction, but may occur in either sex as a result of detrusor muscle failure (atonic bladder). This may be idiopathic but more commonly results from pelvic nerve damage from surgery (e.g. hysterectomy or rectal excision), trauma or infection, or from compression of the cauda equina from disc prolapse, trauma or tumour. USS reveals a significant post-micturition volume (>100 ml). Obstructed bladders should be treated surgically. Unobstructed bladders need to be drained, preferably by intermittent self-catheterisation. Urodynamic testing helps clarify the aetiology.

Neurological causes: Neurological disease resulting in abnormal bladder function is almost always associated with obvious neurological signs; these are described on page 646.

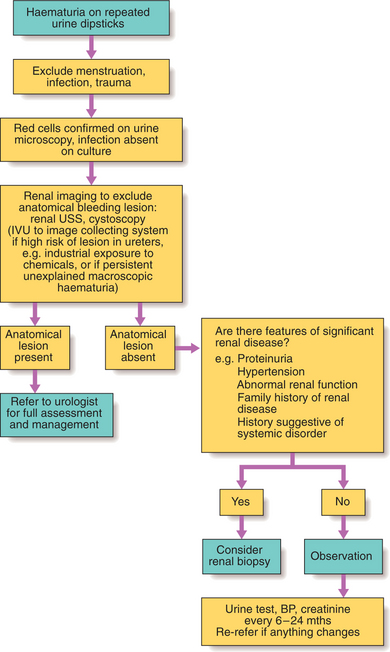

HAEMATURIA

This indicates bleeding anywhere within the urinary tract, and may be visible (macroscopic) or only detectable on urinalysis (microscopic). Macroscopic haematuria is more likely to be caused by tumours, severe infections and renal infarction. Common causes are shown in Box 7.6.

| Renal | Infection, infarction, interstitial disease, glomerular disease, vascular malformation, tumour, cysts, clotting disorders |

| Ureters | Stones, tumour |

| Bladder | Infection, tumour |

| Urethra | Trauma |

Investigations and management of haematuria are outlined in Figure 7.2.

PROTEINURIA

Proteinuria is usually asymptomatic, although large amounts may make urine froth easily.

Moderate amounts of low molecular weight protein do pass through the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). These are normally reabsorbed by tubular cells so that <150 mg/day appears in urine. Minor leakage of albumin into the urine may occur transiently after vigorous exercise, during fever or UTI, and in heart failure. Quantities do not reach nephrotic levels and tests should be repeated once the stimulus is no longer present.

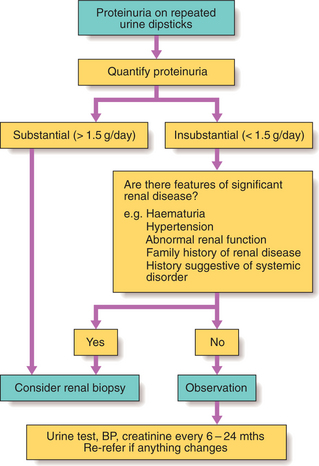

Investigation of proteinuria is shown in Figure 7.3.

MICROALBUMINURIA

Microalbuminuria (0.03–0.3 g/day) is a clear sign of glomerular abnormality and can identify very early glomerular disease, e.g. in diabetic nephropathy (p. 412). Persistent microalbuminuria has also been associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular mortality.

OEDEMA

Causes of oedema are shown in Box 7.7.

7.7 CAUSES OF OEDEMA ![]()

| Low plasma oncotic pressure | Hypoalbuminaemia as seen in nephrotic syndrome, liver failure, malabsorption |

| Increased capillary permeability | Infection, drug-related (calcium channel blockers) |

| Increased hydrostatic pressure | High venous pressure/obstruction (congestive heart failure, DVT, pelvic tumour), lymphatic obstruction (malignancy, radiation injury, congenital abnormality) |

Investigations

The cause of oedema is usually apparent from the history and examination of the cardiovascular system and abdomen, combined with measurement of urinary protein and the serum albumin level. Where ascites or pleural effusions in isolation are causing diagnostic difficulty, aspiration of fluid with measurement of protein and glucose, and microscopy for cells, will usually clarify the diagnosis (p. 276).

HYPERTENSION

Hypertension is a very common feature of renal parenchymal and vascular disease and is an early feature of glomerular disorders. As glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines, hypertension becomes increasingly common, regardless of the renal diagnosis. Control of hypertension is very important in patients with renal impairment because of its close relationship with further decline of renal function (p. 183) and with the adverse cardiovascular risk in renal disease.

ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Acute renal failure (ARF) refers to a sudden and usually reversible loss of renal function, which develops over a period of days or weeks and is usually accompanied by a reduction in urine volume. There are many possible causes (Box 7.8) and it is frequently multifactorial. If the cause cannot be rapidly corrected and renal function restored, temporary renal replacement therapy may be required (p. 185).

7.8 CAUSES OF ARF ![]()

| Pre-renal | |

| Intrinsic renal disease | |

| Post-renal | Obstruction, e.g. stones, tumour, prostatic enlargement |

REVERSIBLE PRE-RENAL ARF

Clinical assessment

Management and prognosis

ESTABLISHED ARF

Established ARF with the histological pattern of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) may develop following severe or prolonged under-perfusion of the kidney (pre-renal ARF). In patients without an obvious cause of pre-renal ARF, alternative ‘renal’ and ‘post-renal’ causes must be considered (Boxes 7.8 and 7.9).

7.9 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ARF IN A HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE, NON-SEPTIC PATIENT ![]()

Urinary tract obstruction

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) (p. 195)