Chapter 27 Kidney and genitourinary tract

• Diuretic drugs: their sites and modes of action, classification, adverse effects and uses in cardiac, hepatic, renal and other conditions.

• Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

• Cation-exchange resins and their uses.

• Drug-induced renal disease: by direct and indirect biochemical effects and by immunological effects.

• Prescribing for renal disease: adjusting the dose according to the characteristics of the drug and to the degree of renal impairment.

• Nephrolithiasis and its management.

• Pharmacological aspects of micturition.

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Diuretic drugs

Definition

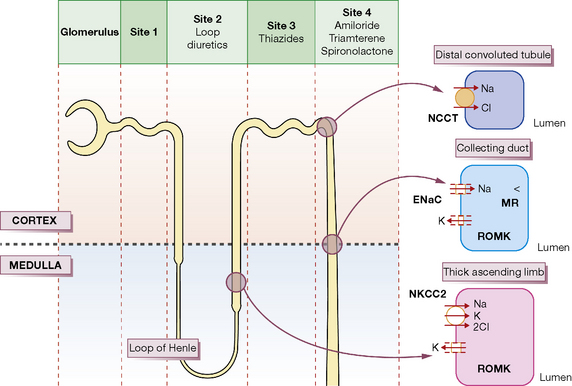

Each day the body produces 180 L of glomerular filtrate which is modified in its passage down the renal tubules to appear as 1.5 L of urine. Thus, if reabsorption of tubular fluid falls by 1%, urine output doubles. Most clinically useful diuretics are organic anions, which are transported directly from the blood into tubular fluid. The following brief account of tubular function with particular reference to sodium transport will help to explain where and how diuretic drugs act; it should be read with reference to Figure 27.1.

Sites and modes of action

Proximal convoluted tubule

Osmotic diuretics such as mannitol are non-resorbable solutes which retain water in the tubular fluid (Site 1, Fig. 27.1). Their effect is to increase water rather than sodium loss, and this is reflected in their special use acutely to reduce intracranial or intraocular pressure and not states associated with sodium overload.

Loop of Henle

The tubular fluid now passes into the loop of Henle where 25% of the filtered sodium is reabsorbed. There are two populations of nephron: those with short loops that are confined to the cortex, and the juxtamedullary nephrons whose long loops penetrate deep into the medulla and are concerned principally with water conservation;1 the following discussion refers to the latter.

The physiological changes are best understood by considering first the ascending limb. In the thick segment (Site 2, Fig. 27.1), sodium and chloride ions are transported from the tubular fluid into the interstitial fluid by the three-ion co-transporter system (i.e. Na+/K+/2Cl− called NKCC2) driven by the sodium pump. The co-transport of these ions is dependent on potassium returning to the lumen through the rectifying outer medullary potassium (ROMK) channel; otherwise potassium would be rate limiting. As the tubule epithelium is ‘tight’ here, i.e. impermeable to water, the tubular fluid becomes dilute, the interstitium becomes hypertonic, and fluid in the adjacent descending limb, which is permeable to water, becomes more concentrated as it approaches the tip of the loop, because the hypertonic interstitial fluid sucks water out of this limb of the tubule. The ‘hairpin’ structure of the loop thus confers on it the property of a countercurrent multiplier, i.e. by active transport of ions a small change in osmolality laterally across the tubular epithelium is converted into a steep vertical osmotic gradient.

The high osmotic pressure in the medullary interstitium is sustained by the descending and ascending vasa recta, long blood vessels of capillary thickness that lie close to the loops of Henle and act as countercurrent exchangers, for the incoming blood receives sodium from the outgoing blood.2Furosemide, bumetanide, piretanide, torasemide and ethacrynic acid act principally at Site 2 by inhibiting the three-ion transporter, thus preventing sodium ion reabsorption and lowering the osmotic gradient between cortex and medulla; this results in the formation of large volumes of dilute urine. Hence, these drugs are called ‘loop’ diuretics.

Distal convoluted tubule

The ascending limb of the loop then re-enters the renal cortex where its morphology changes into the thin-walled distal convoluted tubule (Site 3, Fig. 27.1). Here uptake is still driven by the sodium pump but sodium and chloride are taken up through a different transporter, the Na–Cl co-transporter, called NCC (formerly NCCT). Both ions are rapidly removed from the interstitium because cortical blood flow is high and there are no vasa recta present; the epithelium is also tight at Site 3 and consequently the urine becomes more dilute. Thiazides act principally at this region of the cortical diluting segment by blocking the NCC transporter.

Collecting duct

In the collecting duct (Site 4), sodium ions are exchanged for potassium and hydrogen ions. The sodium ions enter through the epithelial Na channel (called ENaC), which is stimulated by aldosterone. The aldosterone (mineralocorticoid) receptor is inhibited by the competitive receptor antagonist spironolactone, whereas the sodium channel is inhibited by amiloride and triamterene. All three of these diuretics are potassium sparing because potassium is normally secreted through the potassium channel, ROMK (see Fig. 27.1), down the potential gradient created by sodium reabsorption.

Individual diuretics

High-efficacy (loop) diuretics

Furosemide

Furosemide acts on the thick portion of the ascending limb of the loop of Henle (Site 2) to produce the effects described above. Because more sodium is delivered to Site 4, exchange with potassium leads to urinary potassium loss and hypokalaemia. Magnesium and calcium loss are increased by furosemide to about the same extent as sodium; the effect on calcium is utilised in the emergency management of hypercalcaemia (see p. 458).

Moderate-efficacy diuretics

(See also Hypertension, Ch. 24.)

Thiazides

Adverse effects

in general are discussed below. Rashes (sometimes photosensitive), thrombocytopenia and agranulocytosis occur. Thiazide-type drugs increase total plasma cholesterol concentration, but in long-term use this is less than 5%, even at high doses. The questions about the appropriateness of thiazides for mild hypertension, of which ischaemic heart disease is a common complication, are laid to rest by their proven success in randomised outcome comparisons (see Ch. 24).

Bendroflumethiazide

is a satisfactory member for routine use. For a diuretic effect the oral dose is 5–10 mg, which usually lasts less than 12 h, so that it should be given in the morning. As an antihypertensive, 2.5 mg is commonly prescribed. However, this dose does not achieve maximal blood pressure reduction in patients with salt-dependent hypertension (which includes most patients receiving a blocker of the renin–angiotensin system), and has not been shown to prevent strokes or heart attacks. New guidance is likely to recommend some return to higher doses – and/or greater use of the thiazide-like diuretics (below), with or without co-prescribed K+-sparing diuretic. Important potassium depletion is uncommon, but plasma potassium concentration should be checked in potentially vulnerable groups such as the elderly (see Ch. 25). If marked hypokalaemia occurs hyperaldosteronism should be excluded.

Low-efficacy diuretics

Spironolactone

(Aldactone) is structurally similar to aldosterone and competitively inhibits its action in the distal tubule (Site 4; exchange of potassium for sodium); excessive secretion of aldosterone contributes to fluid retention in hepatic cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, congestive heart failure (see specific use in Ch. 25) and primary hypersecretion (Conn’s syndrome). Spironolactone is also useful in the treatment of resistant hypertension, where increased aldosterone sensitivity is increasingly recognised as a contributory factor.

Adverse effects. Oestrogenic effects are the major limitation to its long-term use. They are dose dependent, but in the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES)3 (see Ch. 25) even 25 mg/day caused breast tenderness or enlargement in 10% of men. Women may also report breast discomfort or menstrual irregularities, including amenorrhoea. Minor gastrointestinal upset also occurs and there is increased risk of gastroduodenal ulcer and bleeding. These are reversible on stopping the drug. Spironolactone is reported to be carcinogenic in rodents, but many years of clinical experience suggest that it is safe in humans. Nevertheless, the UK licence for its use in essential hypertension was withdrawn (i.e. possible use long term in a patient group that includes the relatively young), but is retained for other indications.

Indications for diuretics

• Oedema states associated with sodium overload, e.g. cardiac, renal or hepatic disease, and also without sodium overload, e.g. acute pulmonary oedema following myocardial infarction. Note that oedema may also be localised, e.g. angioedema over the face and neck or around the ankles with some calcium channel blockers, or due to low plasma albumin, or immobility in the elderly; in none of these circumstances is a diuretic indicated.

• Hypertension, by reducing intravascular volume and probably by other mechanisms too, e.g. reduction of sensitivity to noradrenergic vasoconstriction.

• Hypercalcaemia. Furosemide reduces calcium reabsorption in the ascending limb of the loop of Henle, which action may be utilised in the emergency reduction of raised plasma calcium levels in addition to rehydration and other measures.

• Idiopathic hypercalciuria, a common cause of renal stone disease, may be reduced by thiazide diuretics.

• The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) may be treated with furosemide if there is a dangerous degree of volume overload (see also p. 423).

• Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, paradoxically, may respond to diuretics which, by contracting vascular volume, increase salt and water reabsorption in the proximal tubule, and thus reduce urine volume.

Therapy

Congestive cardiac failure

The main account appears in Chapter 25, where the emphasis is now on early use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and β-adrenoceptor antagonists that are specifically diuretic sparing. But oral diuretics are easily given repeatedly, and lack of supervision can result in insidious over-treatment. Relief at disappearance of the congestive features can mask exacerbation of the low-output symptoms of heart failure, such as tiredness and postural dizziness due to reduced blood volume. A rising blood urea level is usually evidence of reduced glomerular blood flow consequent on a fall in cardiac output, but does not distinguish whether the cause of the reduced output is over-diuresis or worsening of the heart failure itself. The simplest guide to the success or failure of diuretic regimens is to monitor body-weight, which the patient can do equipped with just bathroom scales. Fluid intake and output charts are more demanding of nursing time, and often less accurate.