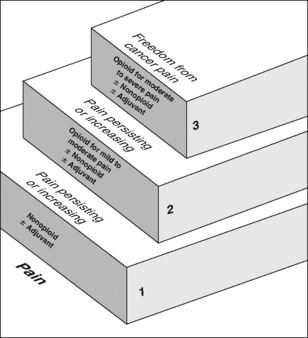

Chapter 12 As discussed in Section III, a multimodal regimen combines drugs with different underlying mechanisms, such as nonopioids, opioids, local anesthetics, and anticonvulsants. This approach allows lower doses of each of the drugs in the treatment plan, which lowers the potential for each to produce adverse effects (Ashburn, Caplan, Carr, et al., 2004; Kim, Kim, Nam, et al., 2008; Marret, Kurdi, Zufferey, et al., 2005; Schug, 2006; Schug, Manopas, 2007; White, 2005). Further, multimodal analgesia can result in comparable or greater pain relief than can be achieved with any single analgesic (Busch, Shore, Bhandari, et al., 2006; Cassinelli, Dean, Garcia, et al., 2008; Huang, Wang, Wang, et al., 2008). Multimodal analgesia is discussed most often in the context of acute pain treatment; however, pain has multiple underlying mechanisms and is a multifaceted phenomenon, underscoring the importance of using a multimodal approach to manage all types of pain; this should be the rule, rather than the exception (Argoff, Albrecht, Irving, et al., 2009; Kehlet, Wilmore, 2008; Kehlet, Jensen, Woolf, 2006) (see Section I). A sound treatment plan relies on the selection of appropriate analgesics from the opioid, nonopioid, and adjuvant analgesic groups. Probably the most well-known example of combining analgesics from the nonopioid, opioid, and adjuvant analgesic groups is the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (Figure 12-1), which was proposed in the early 1980s as a guide to the management of persistent cancer pain (WHO, 1986; Meldrum, 2005). Still today, it is the clinical model for pain therapy (Ripamonti, Bandieri, 2009). The analgesic ladder focuses on selecting analgesics on the basis of the intensity of the pain using analgesics from each of the analgesic groups and, to some extent, building on previously effective analgesics. Step 1 of the analgesic ladder addresses mild pain by suggesting a nonopioid analgesic, such as acetaminophen or an NSAID, and the possibility of an adjuvant analgesic, particularly if the patient has neuropathic pain. It should be noted, however, that the term adjuvant, when used in this ladder, refers to both the adjuvant analgesics and the adjuvant drugs that are added to analgesics to reduce adverse effects (e.g., laxatives for opioid-induced constipation; see Chapter 19). If pain is mild to moderate and not relieved by a nonopioid (with or without an adjuvant), step 2 recommends adding an opioid. In other words, the next level of analgesia builds on the previous analgesics. If a nonopioid relieves some but not enough pain, it is continued and an opioid is added. This action, of course, must be predicated on an assessment that indicates the favorable risk:benefit ratio for the continued treatment with the nonopioid drug. Although, in the past, the decision to stop the nonopioid and start an opioid rather than add an opioid to the nonopioid often was considered merely a common mistake, new information about the gastrointestinal (GI) and the cardiovascular (CV) risk of NSAID therapy alters this view. Rather, the decision to use or continue an NSAID cannot be mostly determined by the pain intensity, or the analgesic ladder guideline, but rather, must be decided based on an evaluation of cumulative risk over the remaining time (see Chapter 6). In clinical practice, the reason for having step 2 is to assist the clinician in selecting an opioid that may be conventionally preferred for the treatment of moderate to severe pain in the patient who is opioid-naïve, or nearly so. For example, mild to moderate pain is often treated with oral analgesics in a fixed combination of opioid and nonopioid, usually acetaminophen or sometimes aspirin (see Chapter 5). Although the problem with fixed combinations is that the dose of acetaminophen (or other nonopioid) limits the escalation of the opioid dose, the benefit is that it helps the clinician to select a formulation that is generally safe for the patient with very limited opioid exposure (and also allows a potentially more convenient way of combining the nonopioid and opioid). Common examples of opioid/nonopioid fixed combinations are as follows: • Lortab 5/500 (hydrocodone 5 mg, and acetaminophen 500 mg) • Percocet (oxycodone 5 mg, and acetaminophen 325 mg) • Tylenol No. 3 (codeine 30 mg, and acetaminophen 300 mg) • Tylox (oxycodone 5 mg, and acetaminophen 500 mg) Opioid analgesics recommended at step 3 should be available orally and by a variety of other routes of administration so that the opioid need not be changed if the route of administration must change. For example, if a patient taking oral morphine has a temporary episode of nausea and vomiting, morphine may be continued by administering it by other routes, such as rectally or subcutaneously. Many opioids, such as morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl, are available by a variety of routes of administration (see Chapter 14). The existence of active metabolites should be considered when selecting an opioid for long-term therapy. Morphine has active metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide [M6G] and morphine-3-glucuronide [M3G]. These metabolites accumulate in patients with renal dysfunction and may be associated with toxicity (Johnson, 2007). Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is a common alternative to morphine, and a modified-release formulation is available in some countries and most recently in the United States. Hydromorphone’s metabolite (hydromorphone-3-glucouronide) can also accumulate in patients with renal dysfunction (Johnson, 2007), but the clinical consequences appear to be limited (Kurella, Bennett, Chertow, 2003). Nonetheless, it has been noted that opioid toxicity can recur when morphine is replaced with hydromorphone in patients with renal dysfunction, and dose should be reduced in such patients (Launay-Vacher, Karie, Fau, et al., 2005). Cautious use of fentanyl in patients with renal dysfunction has been suggested as an alternative when metabolite accumulation is a concern (Dean, 2004; Launay-Vacher, Karie, Fau, et al., 2005) (see Chapter 13 for more on morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl). In the early 1980s, studies of the spinal cord changes occurring in the context of peripheral afferent input—changes that were termed central sensitization (Woolf, 1983)—generated interest in the therapeutic potential of interventions that could be implemented before tissue injury occurred, in the hope of blocking or reducing this phenomenon (Dahl, Moiniche, 2004; Grape, Tramer, 2007) (see Section I for more on central sensitization). A multimodal approach that includes local anesthetics to block sensory input and NSAIDs and opioids, which act in the periphery and in the CNS, initiated preoperatively and continued intraoperatively and throughout the postoperative course, was suggested as ideal preemptive analgesic treatment (Woolf, Chong, 1993). Since then, numerous studies have investigated a wide variety of agents and techniques in an attempt to show a preemptive analgesic effect (Dahl, Moiniche, 2004; Moiniche, Kehlet, Dahl, 2002). Unfortunately, these studies showed that this approach alone did not result in major benefits postoperatively. Establishing the link between good pain management and improvements in patient outcomes will require changes in the way health care is administered (Kehlet, Wilmore, 2008; Liu, Wu, 2007a, 2007b). Traditional practices in perioperative care, such as prolonged bed rest, withholding oral nutrition for extensive periods, and routine use of tubes and drains, are being increasingly challenged and replaced with evidence-based decision making (Pasero, Belden, 2006). This and other factors have led to the evolution of fast track surgery and enhanced postoperative recovery (Kehlet, Wilmore, 2008). In a review of the literature, Kehlet and Wilmore (2008) describe the evidence that supports key principles of implementing what is referred to as accelerated multimodal postoperative rehabilitation. These are outlined in Box 12-1. Continuous multimodal pain relief is integral to this concept. Tools that can be used to increase evidence-based perioperative pain management practice patterns are emerging. For example, a novel web-based program called PROSPECT (Procedure Specific Postoperative Pain Management) (http://www.postoppain.org), established by an international team of surgeons and anesthesiologists, posts evidence-based recommendations and algorithms to guide the health care team in decision making with regard to pain management according to specific surgical procedures (Pasero, 2007). The clinical presentation of persistent postsurgical or post-trauma pain is primarily the patient’s report of the features characteristic of neuropathic pain, such as continuous burning pain and pain beyond the expected time of pain resolution (see Section II for assessment of neuropathic pain). Strategies for preventing these persistent pain states are being investigated, but sustained multimodal pharmacologic approaches that target the underlying mechanisms of neuropathic pain described earlier in this section are recommended (Kehlet, Jensen, Woolf, 2006). See Section I for the underlying mechanisms of the pathology of pain and more on persistent postsurgical pain, and Sections III, IV, and V for discussion of the role of the various analgesics and techniques in the prevention of persistent postsurgical and posttrauma pain.

Key Concepts in Analgesic Therapy

Multimodal Analgesia

WHO Analgesic Ladder for Cancer Pain Relief

Steps 1, 2, and 3

Preemptive Analgesia for Postoperative Pain Management

Accelerated Multimodal Postoperative Rehabilitation

Persistent Postsurgical Pain

Key Concepts in Analgesic Therapy

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree