Answers

A.1 The clinical history is of utmost importance in the assessment of a neurological illness. In a patient presenting with unilateral limb weakness and sensory disturbance, questions should be directed at gaining clues to aid in neuroanatomical localization. Jack has left leg weakness and numbness, which may potentially be attributed to a lesion(s) in the: 1) right cerebral hemisphere; 2) brainstem; 3) spinal cord; 4) left lumbosacral nerve roots and plexus; 5) peripheral nerves of the left lower limb.

You should clarify whether the neurological complaints are confined to the left lower limb. If Jack has also experienced symptoms in his left upper limb (i.e. hemiparesis) it suggests that the lesion may be localized above the cervical spinal cord, e.g. internal capsule of the right cerebral hemisphere. On the other hand, if Jack has also noted symptoms in his right lower limb (i.e. paraparesis) it is likely that he has a thoracic or lumbar spinal cord lesion. However, it should be noted that bilateral leg weakness may rarely be attributed to a parasagittal intracranial lesion centred on the sensorimotor cortex.

History-taking is also important in establishing a differential diagnosis of possible underlying aetiologies. The onset of the limb weakness is important. A sudden onset raises the possibility of a vascular cause, e.g. stroke. If there was history of preceding trauma, stretch-induced or direct peripheral nerve injuries need to be considered. A gradual and progressive history raises the possibility of a neoplastic lesion. A history of fevers and lethargy should be sought to exclude the possibility of an infective lesion.

The past medical history of the patient needs to be clarified. For example, diabetes mellitus may be associated with myriad neurological presentations which the clinician should be familiar with. A known history of previous malignancy raises the possibility of metastatic cerebral disease. Autoimmune disorders are less common but may also result in neurological deficits. HIV/AIDS is associated with cryptococcal meningitis (fungal infection), as well as lymphoma. A positive family history of neurofibromatosis raises the possibility of nerve sheath tumours, which could account for Jack’s neurological complaints.

A.2 In a patient presenting with an intracranial mass lesion there may be associated symptoms of headaches. Classically, headaches secondary to increased intracranial pressure are described as generalized headaches which may be worse in the mornings and can be associated with nausea and vomiting. Furthermore, these headaches may also be exacerbated by straining or Valsalva manoeuvres. Depending on the location of the mass lesion, there may be other associated neurological deficits. Patients presenting with brainstem lesions typically experience other associated debilitating symptoms such as diplopia, facial numbness and weakness, bulbar dysfunction, etc. The commonest clinical pathologies affecting the spinal canal (e.g. disc prolapse, tumours) generally cause local spinal pain and/or radicular pain (sciatica/femoralgia) which aids in the clinical diagnosis. The absence of pain in the history raises the possibility of non-surgical aetiologies, e.g. demyelination, diabetes, etc.

A.3 The neurological findings are highly suggestive of an upper motor neurone lesion. The classical findings include hypertonia, hyper-reflexia, myoclonus and an extensor plantar response, but may not all be present in a patient. These should be contrasted with the findings found in association with a lower motor neurone (at the level of the anterior horn cell or distal) which are characterized by hypotonia, hyporeflexia and equivocal/flexor plantar response. In Jack’s case, the signs support an upper motor neurone lesion.

Given that the abnormal neurological findings of an upper motor neurone pattern were completely confined to the left lower limb, in theory Jack may have 1) an intracranial lesion centred on the motor cortex or 2) a thoracic spinal cord lesion. In clinical practice, most thoracic spinal cord lesions will result in a sensory level and bilateral abnormal neurological findings, e.g. Brown–Séquard syndrome.

A.4 The clinical diagnosis on the basis of history and examination findings points to an upper motor neurone lesion, i.e. intracranial or spinal. Jack has no history of spinal or radicular pain. He has complained of new-onset headaches. This makes an intracranial lesion more likely.

Pre- and post-contrast CT brain imaging is the initial investigation of choice. This modality is widely available and establishes the diagnosis in the majority of cases where a space-occupying lesion is suspected. MRI brain imaging is more sensitive and offers more sophisticated anatomical delineation in three dimensions, but is limited by cost and availability.

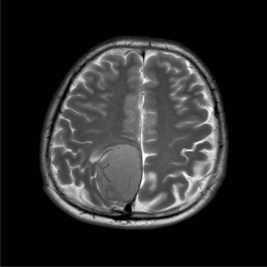

A.5 Figure 41.1 is a T2-weighted MRI image demonstrating the right parasagittal lesion. There is local mass effect with bowing of the falx cerebri. CSF appears ‘white’ (hyperintense). This sequence highlights any cerebral oedema (also hyperintense) which may be associated with a brain tumour. Relatively little oedema is present. Prominent vessels may be seen within the tumour, suggesting hypervascularity.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related