Carrie S. Oliphant

Shannon W. Finks

15-1. Key Points

■ Angina is a syndrome described as discomfort or pain in the chest, arm, shoulder, back, or jaw. Angina is frequently worsened by physical exertion or emotional stress and is usually relieved by sublingual (SL) nitroglycerin (NTG). Patients with angina usually have coronary artery disease (CAD).

■ Anginal symptoms are caused by a decrease in oxygen supply because of reduced blood flow.

■ The goals for treating stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) are to prevent death, reduce symptoms, and improve quality of life.

■ Patients with SIHD should receive aspirin, β-blockers, and statin therapy. Additional anginal control can be obtained by adding on a nitrate, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), or ranolazine (Ranexa). CCBs can be combined with β-blockers (with caution) or used as a substitute because of intolerance.

■ Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) should be prescribed to SIHD patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%, hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), or chronic kidney disease (CKD). Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) can be used as an alternative for ACEI intolerance.

■ Aspirin has been shown to decrease the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI), adverse cardiovascular events, and sudden death in patients with CAD.

■ β-blockers are first-line therapy for treatment of angina in patients with or without a history of MI.

■ Patients prescribed nitrates for treatment of angina need to be counseled on their appropriate use.

■ Ranolazine is a novel antianginal medication that minimally affects blood pressure (BP) or heart rate (HR). It can be used as initial therapy or in combination with other antianginal medications.

■ Upon hospital presentation with unstable angina (UA), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), initial therapy includes morphine, oxygen, nitroglycerin, and aspirin. If there are no contraindications, patients should be given aspirin therapy for life.

■ The first-line anti-ischemic therapy for the treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a β-blocker and should be given orally within the first 24 hours. If chest pain continues, intravenous NTG can be considered.

■ Patients who receive a stent will need dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). For a non-ACS indication with bare metal stent (BMS), at least 1 month of DAPT is required. For ACS indications or for drug-eluting stent (DES) placement, 12 months of DAPT is recommended. Patients treated medically following an ACS event will need aspirin indefinitely and DAPT with clopidogrel or ticagrelor for a minimum of 12 months. Prasugrel (Effient) is not recommended in patients not receiving a stent. DAPT may be considered beyond 15 months following DES in some patients.

■ To reduce the risk of major bleeding, clopidogrel (Plavix) and ticagrelor (Brilinta) should be held for 5 days and prasugrel for 7 days prior to major surgery (e.g., coronary artery bypass graft [CABG]).

■ All medically managed patients presenting with UA or NSTEMI should receive anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin (UFH), enoxaparin (Lovenox), or fondaparinux (Arixtra). If a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is planned, acceptable options include UFH, enoxaparin, or bivalirudin (Angiomax).

■ All patients presenting with STEMI who are undergoing primary PCI should receive anticoagulation with UFH or bivalirudin. If thrombolytic therapy is the chosen reperfusion strategy, anticoagulant options include UFH, enoxaparin, or fondaparinux.

■ Following presentation for ACS, all patients with pulmonary congestion or an LVEF ≤ 40% should receive an ACEI within 24 hours unless contraindicated. Therapy should be continued indefinitely for patients with heart failure, LVEF ≤ 40%, HTN, or DM. An ARB can be used if the patient is ACE intolerant. Aldosterone blockade should be considered post-MI in patients with an LVEF ≤ 40% and either symptomatic HF or DM.

■ Secondary prevention of MI should include DAPT, β-blockers, ACEIs, and statin therapy in all patients who have no contraindications.

15-2. Study Guide Checklist

The following topics may guide your study of this subject area:

■ Risk factors for ischemic heart disease (IHD)

■ Optimal acute and chronic medical treatment for SIHD and ACS

■ Actions of medications used to treat patients with SIHD, ACS, and PCI

■ Indications for medications used to treat SIHD, UA, NSTEMI, and STEMI

■ Trade names, available dosage forms, and dosing frequency, particularly the “Top 100 Drugs” for 2012

■ Major adverse drug reactions of medications used to treat SIHD and ACS

■ Significant drug interactions of medications used to treat SIHD and ACS

■ Differences in therapy between UA, NSTEMI, and STEMI

■ Secondary prevention strategies and post-ACS discharge medications

■ Any unique counseling points for patients discharged with SIHD, ACS, or post-PCI

15-3. Introduction

Definitions

■ Ischemia: Lack of oxygen from inadequate perfusion caused by an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand.

■ Ischemic heart disease (IHD): Disease caused most frequently by atherosclerosis. IHD may present as silent ischemia, chest pain (at rest or on exertion), or myocardial infarction (MI).

■ Angina: Syndrome classically described as discomfort or pain in the chest, arm, shoulder, back, or jaw. Angina is frequently worsened by physical exertion or emotional stress and usually relieved by sublingual (SL) nitroglycerin (NTG). Patients with angina usually have coronary artery disease (CAD).

■ Atypical angina: Transient pain or discomfort lacking one or more of the criteria of classic angina. Atypical angina is more common in women, elderly patients, and diabetics.

■ Acute coronary syndrome (ACS): Syndrome encompassing the following:

• Unstable angina (UA)

• Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

• ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

■ Coronary artery disease: An atherosclerotic disease of the coronary arteries that typically cycles in and out of the clinically defined phases of ACS and asymptomatic, stable, or progressive angina.

■ Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI): Procedure to reopen a partially or completely occluded coronary vessel to restore blood flow.

■ Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG): Surgical procedure in which an artery such as the left internal mammary or a vein from the leg is attached to the heart as a new coronary vessel in order to bypass a diseased vessel.

Epidemiology of IHD

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major cause of death in the United States. Approximately 82.6 million adult Americans have some type of CVD, which includes IHD, high blood pressure (BP), heart failure (HF), stroke, and congenital defects.

According to the American Heart Association (AHA) Heart Disease and Stroke 2014 Statistical Update, coronary heart disease is a cause of one in every six deaths in the United States. Evidence suggests that 47% of the decrease in CAD deaths over the past four to five decades is due to increased use of evidence-based medical therapy and improvements in lifestyle modification strategies.

15-4. Normal Physiology and Pathophysiology

Coronary arterioles change their resistance and dilate as needed to enable the heart to receive a fixed amount of oxygen (O2). Increases in myocardial O2 demand (MVO2) such as physical exertion or an increase in BP causes the arterioles to dilate to maintain O2 supply to the heart. In atherosclerosis, plaque narrows the larger conductance vessels, causing the arterioles to dilate under normal or resting conditions to prevent ischemia. Stress, exercise, or any increase in MVO2 in the setting of limited O2 supply results in ischemia and angina. Pharmacotherapy for IHD may target determinants of MVO2 (heart rate [HR], myocardial wall tension, contractility) or myocardial O2 supply (coronary flow, vasospasm, diastole).

15-5. Stable Ischemic Heart Disease (SIHD) and Prinzmetal’s or Variant Angina

Clinical Presentation

SIHD

Symptoms are caused by decreased O2 supply secondary to reduced flow. Angina is considered stable if symptoms have been occurring for several weeks without worsening. Characteristics of stable angina are as follows:

■ Pain located over sternum that may radiate to left shoulder or arm, jaw, back, right arm, or neck

■ Pressure or heavy weight on chest, burning, tightness, deep, squeezing, aching, viselike, suffocating, crushing

■ Duration of 0.5–30 minutes

■ Symptoms often precipitated by exercise, cold weather, eating, emotional stress, or sexual activity

■ Pain relieved by SL NTG or rest

Prinzmetal’s or variant angina

■ This uncommon form of angina is usually caused by spasm without increased MVO2.

■ Most patients have atherosclerosis.

■ Recurrent, prolonged attacks of severe ischemia are characteristic.

■ Patients are often between 30 and 40 years old.

■ Pain usually occurs at rest or awakens the patient from sleep.

■ Electrocardiogram (ECG) shows ST-segment elevation, which returns to baseline when the patient is given NTG.

Pharmacologic Management

SIHD

Goals of therapy are as follows:

■ To prevent MI and death

■ To reduce symptoms of angina and occurrence of ischemia to improve quality of life

Antiplatelets

■ Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) decreases the incidence of MI, adverse cardiovascular events, and sudden death.

■ Clopidogrel has been used as an alternative when aspirin is contraindicated or in combination with aspirin in certain high-risk individuals. Ticlopidine is not recommended because of its poor side effect profile.

■ Newer antiplatelet agents such as prasugrel and ticagrelor have not been studied in the setting of chronic stable angina at this time and are therefore not indicated.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• Aspirin (75–162 mg daily) is recommended in all patients with SIHD (with or without symptoms) in the absence of contraindications.

• Clopidogrel (75 mg daily) is chosen when aspirin is absolutely contraindicated.

• The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is reasonable in certain high-risk patients.

Anti-ischemic therapy

β-blockers

■ Effects on MVO2 are as follows:

• Inhibit catecholamine effects, thereby decreasing MVO2

• Decrease HR (negative chronotrope effects cause a decrease in conduction through the atrioventricular [AV] node)

• Decrease contractility (negative inotrope effects cause a decrease in force of contraction)

• Reduce BP

■ Effects on oxygen supply are as follows:

• β-blockers cause no direct improvement of oxygen supply.

• They increase diastolic perfusion time (coronary arteries fill during diastole) secondary to decreased HR, which may enhance left ventricle (LV) perfusion.

• Ventricular relaxation causes increased subendocardial blood flow.

• Unopposed alpha stimulation may lead to coronary vasoconstriction.

■ Dosing recommendations:

• Start low, go slow.

• Titrate to resting HR of 55–60 bpm, maximal exercise HR ≤ 100 bpm.

• Avoid abrupt withdrawal, which can precipitate more severe ischemic episodes and MI; taper over 2 days.

■ Selection of β-blockers is based on the following factors:

• β-blockers with cardioselectivity have fewer adverse effects; they lose cardioselectivity at higher doses.

• The intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA) with acebutolol and pindolol may not be as effective because the reduction in HR would be minimal; therefore, the reduction in MVO2 is small. β-blockers with ISA are generally reserved for patients with low resting HR who experience angina with exercise.

• Lipophilicity is associated with more central nervous system (CNS) side effects.

• β-blockers are preferred in patients with a history of MI, chronic heart failure, high resting HR, and fixed angina threshold.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• β-blockers are used as first-line therapy if not contraindicated in patients with prior MI, ACS, or history of heart failure.

• They are often used as initial therapy in SIHD patients without prior MI.

• They are more effective than nitrates and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) in silent ischemia.

• They are effective as monotherapy or with nitrates, CCBs, ranolazine, or a combination thereof.

• β-blockers should be avoided in patients with primary vasospastic or Prinzmetal’s angina.

• They improve symptoms 80% of the time.

Nitrates

■ Effects on MVO2 are as follows:

• Peripheral vasodilation leads to decreased blood return to the heart (preload), which leads to decreased LV volume, decreased wall stress, and decreased O2 demand.

• Arterial vasodilation (occurring after high doses) leads to decreased peripheral resistance (afterload), decreased systolic BP, and decreased O2 demand.

• Nitrates can cause a reflex increase in sympathetic activity, which may increase HR or contractility and lead to an increase in O2 demand in some patients. This problem can be overcome with the use of a β-blocker.

■ Effects on O2 supply: Dilation of large epicardial coronary arteries and collateral vessels in areas with or without stenosis leads to increased O2 supply.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• SL NTG or NTG spray can be used for the immediate relief of angina.

• Long-acting nitrates should be used as initial therapy to reduce symptoms only if β-blockers or CCBs are contraindicated.

• Long-acting nitrates in combination with β-blockers can be used when initial treatment with β-blockers is ineffective.

• Long-acting nitrates can be used as a substitute for β-blockers if β-blockers cause unacceptable side effects.

• Nitrates are used in patients with CAD or other vascular disease.

• Nitrates are preferred agents in the treatment of Prinzmetal’s or vasospastic angina.

• Nitrates improve exercise tolerance.

• They produce greater effects in combination with β-blockers or CCBs.

Calcium channel blockers

■ Effects on MVO2 are as follows:

• CCBs act primarily by decreasing systemic vascular resistance and arterial BP by vasodilation of systemic arteries.

• They cause decreased contractility and O2 requirement (all CCBs exert varying degrees of negative inotropic effects): verapamil (Calan, Isoptin SR, Verelan) > diltiazem (Cardizem, Cartia, Dilacor XR, Dilt-XR, Tiazac) > nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia)

• Verapamil and diltiazem promote additional decreases in MVO2 by decreasing conduction through the AV node, thereby decreasing HR.

■ Effects on O2 supply are as follows:

• Increased diastolic perfusion time secondary to decreased HR, which may enhance LV perfusion

• Decreased coronary vascular resistance and increased coronary blood flow by vasodilation of coronary arteries

• Coronary vasodilation at sites of stenosis

• Prevention or relief of vasospastic angina by dilation of the epicardial coronary arteries

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• CCBs can be used as initial therapy for reduction of symptoms. They are usually second line when β-blockers are contraindicated.

• They are used in combination with β-blockers when initial treatment with β-blockers is not successful.

• They are used as a substitute for β-blockers if initial treatment with β-blockers causes unacceptable side effects.

• Slow-release, long-acting dihydropyridines and nondihydropyridines are effective in stable angina.

• Avoid using short-acting dihydropyridines.

• Newer-generation dihydropyridines, such as amlodipine or felodipine, can be used safely in patients with depressed LV systolic function and can be used in combination with β-blockers.

Combination therapy: β-blockers and nitrates

■ β-blockers can potentially increase LV volume and LV end-diastolic pressure. Nitrates attenuate this effect.

■ Nitrates increase sympathetic tone and may cause a reflex tachycardia. β-blockers attenuate this response.

Combination therapy: β-blockers and CCBs

■ β-blockers and long-acting dihydropyridine CCBs are usually efficacious and well tolerated.

■ CCBs, especially the dihydropyridines, increase sympathetic tone and may cause reflex tachycardia. β-blockers attenuate this effect.

■ β-blockers and nondihydropyridine CCBs should be used together cautiously because the combination can lead to excessive bradycardia or AV block. The combination can also precipitate symptoms of heart failure in susceptible patients.

Ranolazine

■ Unlike β-blockers and CCBs, ranolazine’s antianginal and anti-ischemic effects occur without causing any significant hemodynamic changes in BP or HR.

■ The mechanism of action is not clearly understood, but it appears to inhibit the late Na current (INa) during ischemic conditions, preventing Ca overload and ultimately blunting the effects of ischemia by improving myocardial function and perfusion.

■ Ranolazine is indicated for the treatment of chronic angina and can be used in combination with β-blockers, CCBs, or nitrates.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

■ Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) reduce the incidence of MI, cardiovascular death, and stroke in patients at high risk for vascular disease.

■ Low-risk patients with SIHD and normal or slightly reduced LV function may not benefit from ACEI therapy as greatly as high-risk patients.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• ACEIs should be used in patients with SIHD who also have left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40%, hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease (CKD) unless contraindicated.

• They are used in high-risk patients with CAD (by angiography or previous MI) or other vascular disease.

• It is reasonable to consider angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients who have LVEF ≤ 40%, hypertension, diabetes, or CKD but are intolerant of ACEIs.

Lipid-lowering therapy

■ Lipid-lowering therapy is recommended in patients with established CAD, including SIHD, even if only mild or moderate elevations of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol are present.

■ Omega-3 fatty acids can be encouraged in either dietary consumption or capsule form (1 g daily) for risk reduction; higher doses are recommended for treatment of elevated triglycerides.

■ Therapeutic options to treat triglycerides or non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol include niacin and fibrates (after appropriate LDL-lowering therapy with statins).

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• Moderate- to high-intensity statins are indicated in patients with documented or suspected CAD.

• A combination of statins with other lipid-lowering therapy requires careful monitoring for the development of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis.

Prinzmetal’s or variant angina

■ β-blockers have no role in management and may increase painful episodes.

■ β-blockers may induce coronary vasoconstriction and prolong ischemia.

■ Nitrates are often used for acute attacks.

■ CCBs, such as nifedipine, amlodipine (Norvasc), diltiazem, or verapamil, may be more effective, may be dosed less frequently, and have fewer side effects than nitrates.

■ Nitrates can be added if there is no response to CCBs.

■ Combination therapy with nifedipine + diltiazem or nifedipine + verapamil has been reported to be useful.

■ Dose titration is recommended to obtain efficacy without unacceptable side effects.

■ Treat acute attacks, and provide prophylactic treatment for 6–12 months.

15-6. Acute Coronary Syndrome

ACS is composed of UA, NSTEMI, and STEMI.

Pathophysiology

Tissue ischemia is a result of a mismatch between O2 supply and demand. Most commonly, the process of ischemic syndromes involves two essential events:

■ Disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque resulting in platelet aggregation

■ Formation of a platelet-rich thrombus

The clinical manifestation depends on the extent and duration of the thrombotic occlusion. In UA or NSTEMI, the thrombus does not completely occlude the vessel. UA and NSTEMI are often indistinguishable by symptoms or ECG changes alone but can be differentiated by the presence or absence of positive biomarkers (Table 15-1).

UA and NSTEMI may evolve into STEMI without treatment. In STEMI, the thrombus completely occludes the coronary artery. If left untreated, this occlusion can result in sudden cardiac death.

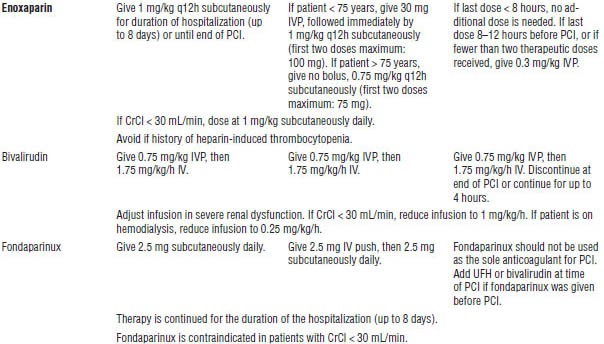

Table 15-1. Cardiac Enzymes and ECG Changes: UA versus NSTEMI/STEMI

Presentation

■ Central or substernal or crushing chest pain can radiate to the neck, jaws, back, shoulders, and arms.

■ Patients may present with diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, arm tingling, weakness, shortness of breath, or syncope.

■ Pain may be similar to typical angina except that the occurrences are more severe, may occur at rest, and may be caused by less exertion than typical angina.

■ ACS symptoms may be incorrectly interpreted as dyspepsia or indigestion.

■ Pain is not usually relieved by SL NTG or rest.

Diagnosis

UA and NSTEMI

■ Angina occurring at rest and persisting longer than 20 minutes; new onset angina resulting in marked limitations of normal activity; or angina that occurs more frequently, lasts longer, or occurs at a lower threshold of activity

■ Cardiac enzymes (positive in NSTEMI) and ECG changes (ST depression, T-wave inversions, or transient ST elevation)

STEMI

■ Similar clinical presentation as UA, NSTEMI, or both; ST-segment elevation on the ECG and elevations of cardiac enzymes

■ New left bundle branch block is considered a STEMI equivalent.

See Table 15-1 for a comparison of ECG changes and cardiac enzymes in ACS.

Goals of Therapy

■ Limit size of infarction or prevent progression to infarction in UA.

■ Completely restore blood flow to the myocardium, resulting in tissue salvage.

■ Prevent MI, arrhythmias, and ischemia.

■ Reduce mortality.

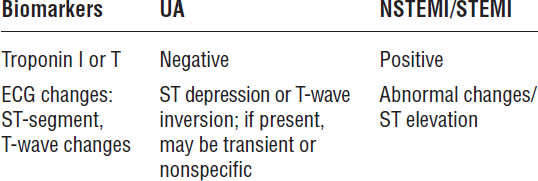

See Table 15-2 for a comparison of UA/NSTEMI and STEMI.

Reperfusion therapy (STEMI)

■ The goal is to open the occluded coronary artery to reestablish blood flow through the use of primary PCI (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] with coronary stenting) or with fibrinolytic therapy.

■ Mechanical reperfusion with PCI has been shown to be more successful and is preferred over fibrinolysis when the patient can be transported to a center with expert capability within 120 minutes of presentation. Primary PCI is discussed in section 15-7.

Fibrinolytic therapy (also known as thrombolytic therapy)

■ Agents (see Table 15-16)

• Reteplase (rPA; Retavase)

• Streptokinase (Streptase)

Table 15-2. Pathophysiology: STEMI versus UA/NSTEMI

• Tenecteplase (TNKase)

• Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; Alteplase)

■ Fibrinolytic therapy improves myocardial O2 supply, limits infarct size, and decreases mortality.

■ Fibrinolytic therapy achieves patency of infarcted artery in less than 60% of cases as compared to 90–100% with primary PCI and thus is not preferred when PCI is available.

■ Fibrin-specific agents (alteplase, reteplase, tenecteplase) are preferred over the non- fibrin-specific agent, streptokinase.

■ Fibrin-specific agents require concomitant anticoagulation for at least 48 hours after and up to 8 days after fibrinolytic therapy or until revascularization is performed.

■ Door-to-needle time of < 30 minutes is an important goal.

■ Signs of successful reperfusion include relief of chest pain, resolution of ST-segment changes, and reperfusion arrhythmias, usually ventricular in nature.

■ Indications for fibrinolytic therapy are as follows:

• ST-segment elevation is > 1 mm in two or more contiguous leads or left bundle branch block is present (obscuring ST observational changes).

• Presentation is within 12 hours of symptom onset and primary PCI is unlikely to be performed within 120 minutes of first medical contact.

• Fibrinolytic therapy can be administered to patients with ongoing ischemia within 12–24 hours of symptom onset.

• It should not be used in UA or NSTEMI patients.

Early Hospital Management of ACS

Morphine, oxygen, nitrates, and aspirin (MONA)

Indications for therapy are shown in Table 15-3.

Anti-ischemic therapy

β-adrenergic blockade

■ In STEMI patients, β-blockers have been shown to reduce the incidence of reinfarction and ventricular arrhythmias.

■ Preference is for an agent without ISA.

■ Agents with β1 selectivity are preferred in patients with bronchoconstrictive disease.

■ No evidence indicates that one agent is superior to another.

Table 15-3. Morphine, Oxygen, Nitrates, and Aspirin Therapy

Medication | Details |

Morphine | Vasodilatory properties on both arterial and venous sides decrease both preload and afterload. Pain relief decreases tachycardia, along with decrease in preload and afterload; all work to decrease MVO2. |

| Increments of 2–4 mg IV are given every 5–15 minutes until pain is relieved. |

| Nausea, vomiting, hypotension, sedation, and respiratory depression may occur. |

| Morphine produces a vagotonic effect that may be contraindicated in patients with bradycardia. Monitor for hypotension, respiratory depression, and allergic reactions. |

Oxygen | Supplemental O2 2–4 L/min by nasal cannula is recommended to correct and avoid hypoxia, particularly within the first 2–3 hours. More aggressive ventilatory support should be considered and given as needed. |

Nitrates | All patients should receive NTG as a sublingual tablet or spray 0.4 mg, if not contraindicated. If pain is unrelieved after one dose, call 911. |

| IV NTG may be used in the first 48 hours in the setting of ongoing chest pain, pulmonary congestion, or hypertension. |

| NTG should not be administered to patients with hypotension (SBP < 90 mm Hg), severe bradycardia, or suspected right ventricular infarction. Patients with right ventricular infarction are dependent on preload to maintain cardiac output, and the use of NTG could cause profound hypotension. |

| Long-acting nitrates should be used as secondary prevention in patients who do not tolerate β-blockers and CCBs. These nitrates can be used in patients who have continual chest pain despite the use of β-blockers and CCBs. Nitrates are contraindicated if sildenafil or vardenafil has been used within 24 hours or within 48 hours of tadalafil administration. |

Aspirin | Nonenteric-coated aspirin 162–325 mg should be given at the onset of chest pain unless contraindicated. Chew and swallow the first dose. |

| A dose of 81–162 mg should be taken daily for life thereafter. |

| Aspirin 81 mg daily after PCI is preferred over higher maintenance doses. |

| Clopidogrel may be substituted if a true aspirin allergy is present or if the patient is considered unresponsive to aspirin. |

■ Initial choices include metoprolol and atenolol.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• β-blockers should be used in all patients without contraindications.

• The first dose should be given orally within the first 24 hours unless contraindications exist, including signs of heart failure, symptoms of low output state, increased risk of cardiogenic shock, or other relative contraindications (e.g., bradycardia, hypotension, heart block, active asthma, reactive airway disease). In patients who are hypertensive at the time of presentation, the intravenous (IV) route can be used.

Nitrates

Nitrates are discussed in Table 15-3.

Calcium channel blockers

■ There is no mortality benefit from the use of CCBs; therefore, they are not recommended as first-line therapy.

■ Indications for therapy are as follows:

• In patients with contraindications to β-blockers or with recurrent ischemia receiving β-blockers and nitrates, a nondihydropyridine CCB (verapamil, diltiazem) can be used in the absence of significant LV dysfunction or other contraindications.

• Oral long-acting dihydropyridine CCBs can provide additional control of hypertension or anginal symptoms in patients who are already receiving β-blockers and nitrates.

• In general, short-acting dihydropyridines should be avoided. If used, combine with a β-blocker.

Antiplatelet therapy or dual antiplatelet therapy

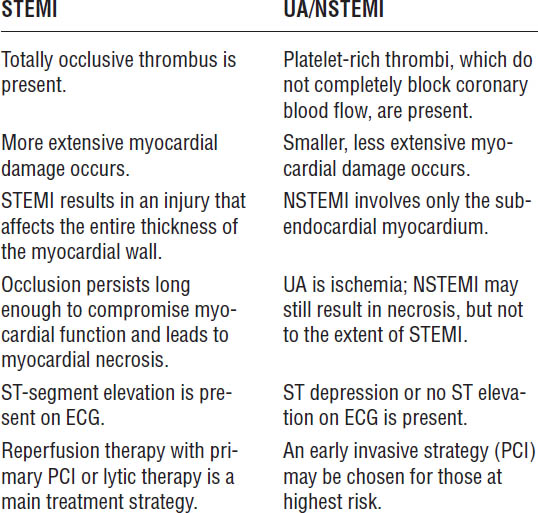

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant strategies for ACS and PCI are outlined in Table 15-4.

Oral antiplatelet therapy

■ Aspirin plus a P2Y12 receptor antagonist (thienopyridines or ticagrelor, a cyclopentyltriazolopyrimidine) reduces rates of atherothrombotic events in patients with ACS and reduces risk of stent thrombosis after PCI.

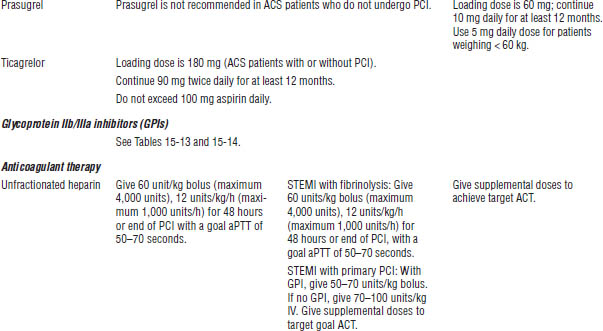

Table 15-4. Recommendations for Evidenced-Based Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapies for the Management of ACS

ACT, activated clotting time; BMS, bare metal stents; CrCl, creatinine clearance; DES, drug-eluting stents; IVP, IV push.

Boldface indicates one of top 100 drugs for 2012 by units sold at retail outlets, www.drugs.com/stats/top100/2012/units.

■ The mechanism of platelet aggregation for the P2Y12 receptor antagonists and aspirin differ; therefore, their effects are additive; bleeding risk is higher with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) over aspirin alone.

P2Y12 receptor antagonists

Thienopyridines

■ Clopidogrel and prasugrel are the members of this class.

■ Inhibition of platelet aggregation is irreversible.

■ Therapy is initiated with a loading dose for a more rapid effect.

Cyclopentyltriazolopyrimidine

■ Ticagrelor is the only medication in this class.

■ Inhibition of platelet aggregation is reversible, although it should still be held 5 days before major surgery to reduce the risk of bleeding.

■ The drug has a unique side effect profile compared to the other P2Y12 receptor antagonists because of inhibition of adenosine reuptake.

■ A loading dose is given to initiate therapy for a more rapid effect.

■ Twice-daily dosing is different from other P2Y12 receptor antagonists and is an important consideration for patient adherence.

Indications for antiplatelet therapy

Clopidogrel

■ Reduces rate of atherothrombotic events (MI, stroke, vascular deaths) in patients with recent MI or stroke or with established peripheral arterial disease

■ Reduces rate of atherothrombotic events in patients with UA or NSTEMI managed medically or with PCI (with or without stent)

■ Reduces rate of death and atherothrombotic events in patients with STEMI managed medically

Prasugrel

■ Prasugrel is used to reduce thrombotic cardiovascular events (including stent thrombosis) in patients with ACS who are to be managed with PCI.

■ Prasugrel is contraindicated in patients with previous stroke or TIA.

Ticagrelor

■ Ticagrelor is used in conjunction with aspirin (< 100 mg daily) to reduce the rate of death and atherothrombotic events in patients with ACS managed medically or with PCI.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors (GPIs) are discussed in section 15-7. Also refer to Tables 15-4, 15-13, and 15-14.

Agents

■ Abciximab (ReoPro)

■ Eptifibatide (Integrilin)

■ Tirofiban (Aggrastat)

Indications for therapy

All of these agents can be used as adjunctive therapy in patients undergoing PCI. Use of these agents in the setting of PCI is covered in Table 15-4.

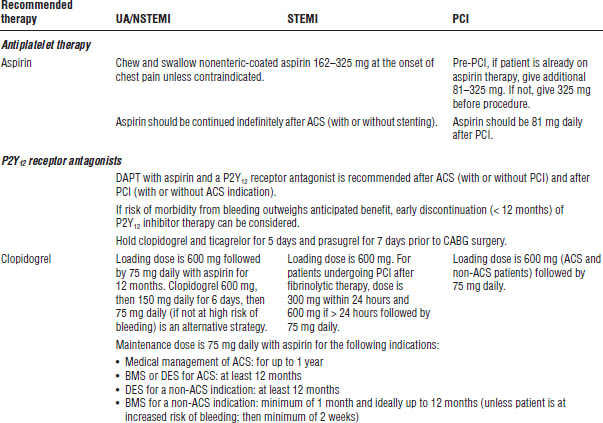

Anticoagulant therapy

Anticoagulant therapy should be added to antiplatelet therapy as soon as possible following presentation of ACS. Acceptable options include unfractionated heparin (UFH), enoxaparin, bivalirudin, and fondaparinux (see Table 15-4).

Agent selection depends on type of ACS, management strategy (invasive versus conservative), and the need for a surgical procedure (CABG).

Indications for anticoagulant therapy are as follows:

■ UA and NSTEMI

• In patients with a planned conservative strategy (i.e., medical management), enoxaparin, UFH, and fondaparinux are options.

• Fondaparinux is preferred in patients who are considered a high bleeding risk.

• For patients with a planned PCI procedure, the preferred agents include UFH, enoxaparin, and bivalirudin.

■ STEMI

• For patients with a planned PCI procedure, the preferred agents include UFH, enoxaparin, and bivalirudin.

• UFH, enoxaparin, or fondaparinux can be used in patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy.

Unfractionated heparin

■ UFH indirectly inhibits thrombin by accelerating the body’s own natural antithrombin.

■ UFH is continued for 48 hours or until a PCI procedure is completed.

Enoxaparin

■ Enoxaparin is a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).

■ LMWH differs from UFH in size and affinity for thrombin.

■ Advantages of LMWH over UFH include better bioavailability, more predictable response, ease of administration, fewer side effects, and no recommended routine monitoring.

■ Enoxaparin is continued for the duration of the hospitalization (up to 8 days) or until a PCI procedure is completed.

Bivalirudin

■ Bivalirudin is a direct thrombin inhibitor.

■ Bivalirudin differs from UFH in that it can inhibit both clot-bound and free thrombin.

■ Studies have shown that bivalirudin is noninferior to heparin plus GPI, but with less bleeding.

■ Bivalirudin is continued until the angiography or PCI procedure is completed.

Fondaparinux

■ Fondaparinux is an indirect factor Xa inhibitor.

■ Fondaparinux has no effect on thrombin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree