CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Modified from Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice. Circulation 2003;107:499–511.

Prevention

- Treatment of cardiovascular risk factors has resulted in a 50% decrease in deaths from CHD over the past few decades.20 Despite impressive declines in mortality, CVD, which includes CHD, stroke/TIA, and PAD, remains the leading cause of death in men and women worldwide.21

- The majority of known risk factors for CVD are modifiable by preventive measures, including lifestyle changes and adjunctive pharmacotherapy. The INTERHEART study demonstrated that nine modifiable risk factors account for over 90% of the risk of an initial acute myocardial infarction.22 Importantly, the presence of multiple risk factors confers at least additive risk.23

- Assessment of risk in primary prevention should not be limited to risk for CHD but should also include risk for CVD events. This is of particular concern in women who have a higher stroke burden than men.5

- A GRS can be calculated to determine the absolute risk of an atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) event over a specified time period, usually 10 years, based on the presence of major risk factors without known CHD or CHD risk equivalent. Risk calculators include the following:

- The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk calculator based on the Pooled Cohort Equations and lifetime risk prediction tools (http://www.cardiosource.org/science-and-quality/practice-guidelines-and-quality-standards/2013-prevention-guideline-tools.aspx, last accessed December 23, 2014). These risk estimations were derived from large racially and geographically diverse cohort studies and predict so-called hard cardiovascular events, including stroke. The factors included are age, sex, race (non-Hispanic white vs. African American), systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive therapy, total and HDL cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking. Formal estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk is recommended beginning at age 40 and should be repeated every 4 to 6 years in adults 40 to 79 years of age who are free from ASCVD. Due to limitations of the data, calculated risks for Hispanics and Asian Americans may be overestimated.14

- The Framingham Risk Score (FRS) for the prediction of CHD events (angina, MI, or coronary death) (http://cvdrisk.nhlbi.nih.gov/calculator.asp, last accessed December 23, 2014). The Framingham Study included only middle-aged Caucasian patients and assesses only the risk of developing CHD. The generalizability of the Framingham Risk Score to other populations remains questionable.

- Other GRS include SCORE (Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation) for CVD death, the Reynolds Risk Score for major CVD events, and the JBS3 (Joint British Societies) risk calculator for estimating both CVD risk and the impact of beneficial interventions (http://www.jbs3risk.com, last accessed December 23, 2014).

- The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk calculator based on the Pooled Cohort Equations and lifetime risk prediction tools (http://www.cardiosource.org/science-and-quality/practice-guidelines-and-quality-standards/2013-prevention-guideline-tools.aspx, last accessed December 23, 2014). These risk estimations were derived from large racially and geographically diverse cohort studies and predict so-called hard cardiovascular events, including stroke. The factors included are age, sex, race (non-Hispanic white vs. African American), systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive therapy, total and HDL cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking. Formal estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk is recommended beginning at age 40 and should be repeated every 4 to 6 years in adults 40 to 79 years of age who are free from ASCVD. Due to limitations of the data, calculated risks for Hispanics and Asian Americans may be overestimated.14

- Based on the GRS, patients are categorized as low or elevated risk for the development of ASCVD over the next 10 years.

- Low (<7.5%) ASCVD risk patients generally do not need further testing or aggressive risk factor modification with pharmacotherapy, but therapeutic lifestyle interventions are strongly encouraged. Statin therapy may be considered in select patients 21 to 75 years of age (see Lipids below). In patients 20 to 59 years old, it may also be useful to calculate the 30-year or lifetime risk of ASCVD.24

- Elevated (≥7.5%) ASCVD risk patients require intensive risk factor modification, typically through a combination of lifestyle changes and drug therapy, particularly statin medications. Further testing with labs, imaging, or ischemic evaluation is not routinely recommended, but may be indicated based on clinical context. Frequent retesting to determine achievement of specific numeric treatment goals has been discouraged in favor of intermittent assessments of global risk.

- Low (<7.5%) ASCVD risk patients generally do not need further testing or aggressive risk factor modification with pharmacotherapy, but therapeutic lifestyle interventions are strongly encouraged. Statin therapy may be considered in select patients 21 to 75 years of age (see Lipids below). In patients 20 to 59 years old, it may also be useful to calculate the 30-year or lifetime risk of ASCVD.24

- The concept of matching the intensity of risk factor management to the estimated risk of CVD is well established and has resulted in an increased emphasis on the accuracy and reliability of risk assessment. The desire to improve existing risk estimation tools has stimulated interest in finding new risk markers for CVD. On the basis of current, albeit limited, evidence, several novel biomarkers have been identified that show promise for clinical utility. Assessment of one or more of the following may be considered when a risk-based treatment decision is uncertain even after formal risk estimation:

- Family history of premature CVD (first-degree male relative <55 years or female relative <65 years) confers greater risk and supports revising risk assessment upward.

- Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score by computed tomography. A score ≥300 Agatston units suggests higher risk.

- Ankle-brachial index (ABI) ratios <0.9 or >1.3 imply the presence of peripheral vascular disease and thus elevate global CVD risk.

- High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels ≥2 mg/L have been associated with significantly higher rates of CVD events.

- Carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) assessed by ultrasound. CIMT is a measure of arterial wall thickness used to detect subclinical atherosclerosis. At this time, routine measurement of CIMT is not recommended since the added value in risk prediction is small and unlikely to be of clinical importance.25

- Family history of premature CVD (first-degree male relative <55 years or female relative <65 years) confers greater risk and supports revising risk assessment upward.

- Age

- The incidence of MI increases continuously with age, and >83% of people who die from CHD are in the geriatric population.7

- In the FRS, age is the most heavily weighted risk factor; hence, a common critique is that it underestimates risk in younger individuals.

- The incidence of MI increases continuously with age, and >83% of people who die from CHD are in the geriatric population.7

- Lipids

- Lipid management is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

- A fasting lipid profile is the preferred screening test and should be first obtained at age 21 and then reassessed every 4 to 6 years along with other traditional ASCVD risk factors (i.e., age, sex, race, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking).

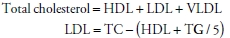

- Total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels are measured directly. Very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) level is estimated by dividing the triglyceride concentration by five.

- LDL may be calculated from the following formula:

- This method is accurate only when triglyceride levels are <400 mg/dL.

- Direct measurement of LDL is possible and necessary if triglycerides levels exceed this threshold.

- HDL is the only nonatherogenic subtype of cholesterol, and elevated HDL levels are considered protective or a negative risk factor. Despite an inverse association between HDL levels and CVD risk, therapies to raise HDL have failed to demonstrate improved outcomes. This is consistent with recent trial data suggesting that low HDL is more likely a biomarker for CHD risk rather than causative of it.26

- Specific numeric therapeutic targets are no longer recommended (e.g., LDL <100 mg/dL). Instead, the emphasis is on moderate- or high-intensity statin treatment in appropriate individuals. The four clear statin benefit groups are24

- Patients ≥21 years old with LDL ≥190 mg/dL

- Patients 40 to 75 years old with DM and LDL of 70 to 189 mg/dL

- Patients 40 to 75 years old without clinical ASCVD or DM but with ≥7.5% 10-year risk of ASCVD (ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations)

- Patients with clinical ASCVD (secondary prevention)

- Patients ≥21 years old with LDL ≥190 mg/dL

- Lipid management is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

- Hypertension

- Blood pressure is directly related to the incidence of cardiovascular events, starting from a systolic BP of 115 mm Hg.27 However, intensive blood pressure regimens with systolic goals <140/90 mm Hg have not been shown to reduce CVD risk in all populations, including diabetics and the elderly.28

- The recently released report of the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) recommends a treatment goal of <140/90 for all patients, except those patients ≥60 years old without DM or CKD, for whom a goal of <150/90 is recommended.29

- One notable exception is in those with systolic dysfunction where the aim is to achieve adequate doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and β-blockers based on tolerability rather than blood pressure levels.

- HTN management is discussed in further detail in Chapter 6.

- Blood pressure is directly related to the incidence of cardiovascular events, starting from a systolic BP of 115 mm Hg.27 However, intensive blood pressure regimens with systolic goals <140/90 mm Hg have not been shown to reduce CVD risk in all populations, including diabetics and the elderly.28

- Cigarette smoking

- Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, and tobacco cessation reduces the risk of cardiovascular events by 25% to 50%.

- Clinical studies have demonstrated the key role of physician counseling in facilitating an individual’s interest and motivation for quitting.

- Nicotine replacement may be helpful for some patients, but oral medications such as bupropion or varenicline may improve cessation rates.

- Smoking cessation is discussed in Chapter 45.

- Secondhand smoke also increases the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality.

- Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States, and tobacco cessation reduces the risk of cardiovascular events by 25% to 50%.

- Aerobic exercise

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends goal activity levels of ≥150 minute/week of moderate intensity and/or ≥75 minute/week of vigorous-intensity exercise are recommended for both primary and secondary preventions of heart disease. Individual episodes of aerobic activity should be at least 10 minutes long and spread throughout the week.30

- The ACC/AHA lifestyle management guidelines to reduce cardiovascular risk recommendations are very similar: three to four sessions per week, lasting on average 40 minutes per session, involving moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.31

- Exercise intensity should progress slowly over time. One method to assess intensity, in those not on AV nodal drugs, is to monitor heart rate.

- Heavy exercise is considered more than 80% of the maximal predicted heart rate calculated as 220 minus age.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends goal activity levels of ≥150 minute/week of moderate intensity and/or ≥75 minute/week of vigorous-intensity exercise are recommended for both primary and secondary preventions of heart disease. Individual episodes of aerobic activity should be at least 10 minutes long and spread throughout the week.30

- Diet

- Dietary modifications can have a powerful and beneficial effect on CVD. In general, a healthy diet emphasizes intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts, beans, high fiber grains, healthy fish at least twice a week (which may exclude tilapia); avoidance of trans fats; minimization of saturated fats in favor of monosaturated fats; and limits intake of red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Total caloric intake should be appropriate for current weight, and calories should be restricted when necessary.31

- Appropriate dietary plans to achieve these goals include the AHA Diet, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Pattern, or the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet.32–35

- Saturated fat intake should be <7% of total energy intake.

- Fiber intake goal is 30 to 45 g/day.

- 200 g/day of fruit and 200 g/day of vegetables should be consumed.

- For those who already drink, alcohol should be limited to 1 drink/day (1 drink = 4 oz of wine or 12 oz of beer or 1 oz of spirits) in women and 1 to 2 drinks/day in men.

- Dietary modifications can have a powerful and beneficial effect on CVD. In general, a healthy diet emphasizes intake of vegetables, fruits, nuts, beans, high fiber grains, healthy fish at least twice a week (which may exclude tilapia); avoidance of trans fats; minimization of saturated fats in favor of monosaturated fats; and limits intake of red meat, sweets, and sugar-sweetened beverages. Total caloric intake should be appropriate for current weight, and calories should be restricted when necessary.31

- Obesity

- Obesity is the fastest growing cardiovascular risk factor. A calculated body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 is considered overweight, while >30 kg/m2 is considered obese. Central obesity is defined as a waist circumference >40 inches for men and >35 inches for women.36

- Target BMI is between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2, and initial weight loss goals should be 5% to 10% of total weight.

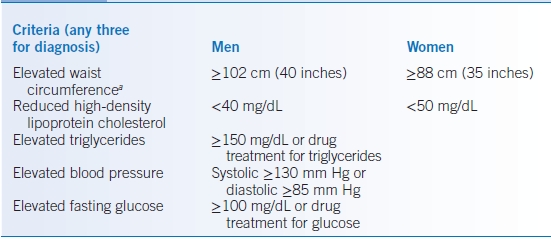

- The metabolic syndrome is correlated with obesity and associated with a higher risk for DM. The diagnostic criteria can be found in Table 7-2.37

- Metabolic syndrome was initially defined to identify patients with insulin resistance at risk for DM and CVD. However, it may not be a unique risk factor whose presence conveys a greater risk than the sum of its parts. Hence, its clinical utility is of uncertain significance. Treatment involves the same lifestyle changes recommended to all patients.38

- Obesity is the fastest growing cardiovascular risk factor. A calculated body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2 is considered overweight, while >30 kg/m2 is considered obese. Central obesity is defined as a waist circumference >40 inches for men and >35 inches for women.36

- Diabetes care in ischemic heart disease

- DM management is important, although intense control is no longer recommended, and it is imperative that therapy does not induce hypoglycemic episodes.28

- Hemoglobin A1c goals of <7% may be considered in those with a short duration of DM and good life expectancy.

- Hemoglobin A1c goals of 7% to 9% may be appropriate in older patients, those with end organ damage from DM, or prior hypoglycemic events.

- Rosiglitazone is contraindicated in patients with IHD/heart failure, although more recent evidence suggests the CVD concerns may have been unjustified.

- DM management is important, although intense control is no longer recommended, and it is imperative that therapy does not induce hypoglycemic episodes.28

TABLE 7-2 American Heart Association Criteria for Metabolic Syndrome

aWaist circumference measured horizontally at the iliac crest, at the end of normal expiration; lower cutoffs may be appropriate in Asian Americans (≥90 cm or ≥35 inches for men, ≥80 cm or ≥31 inches for women).

Modified fromGrundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol 2006;21:1–6.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

History

- The most common manifestation of CAD is angina, which is generally described as a substernal pain or discomfort lasting minutes that is crushing, squeezing, pressure, suffocating, and/or heavy. Angina is not usually sharp or stabbing and does not typically change with respiration or position.39

- Some individuals may experience nausea, diaphoresis, epigastric discomfort, or dyspnea as the primary symptom of angina. Atypical symptoms are more common in women and the elderly.39

- Symptoms can be precipitated by emotional or physical stress or illness.

- Symptoms may radiate into the arm, jaw, neck, or back and are frequently associated with a profound sense of discomfort or uneasiness.

- Typical angina has three features: (a) substernal chest discomfort of a characteristic quality and duration that is (b) provoked by stress or exertion, and (c) relieved by rest or nitroglycerin (NTG).39

- Atypical angina has two of these three characteristics.

- Noncardiac chest pain meets one or none of these characteristics.

- Atypical angina has two of these three characteristics.

- Of note, diabetics may not experience chest discomfort despite having significant CAD, and women and elderly patients often experience more atypical forms of chest discomfort.

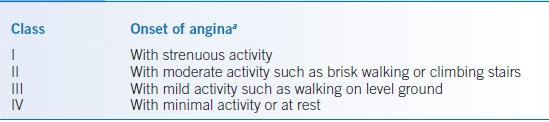

- Since quality of angina varies significantly among individuals, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society has classified the amount of angina in terms of symptomatic limitations to performing daily activities (Table 7-3). This allows clinicians to titrate medical or surgical therapy to reduce anginal severity.40

- When evaluating patients in the ambulatory setting with symptoms suggestive of CHD, the stability of the symptoms is key in determining which patients need inpatient evaluation and which can be cared for in the ambulatory setting. Patients with angina should first be identified as having stable or unstable angina.

- Chronic stable angina is reproducibly precipitated in a predictable manner by exertion or emotional stress and relieved within 5 minutes by sublingual nitroglycerin or rest. To be considered stable, angina symptoms should be present and unchanged for 2 months or greater. These patients can be safely managed in the ambulatory setting.

- Patients with low-risk unstable angina are those with new-onset exertional angina or worsening existing exertional angina whose onset is between 2 weeks and 2 months of presentation with a normal exam, ECG, and cardiac markers. Other low-risk features include age <70 years, pain after exertion <20 minutes duration, lack of rest pain, and pain that is not rapidly worsening. Ambulatory management of these patients is possible, but treatment and testing should not be delayed and close follow-up should be assured.

- Patients with symptoms suggestive of an ACS or its complications (such as acute heart failure exacerbation) should be referred for prompt inpatient hospital evaluation and management.

TABLE 7-3 Classification of Angina

aUnstable angina is generally considered class IV angina, or progression of classes II–III angina over the preceding 2 months.

Modified from Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoris. Circulation 1976;54:522–523.

Physical Examination

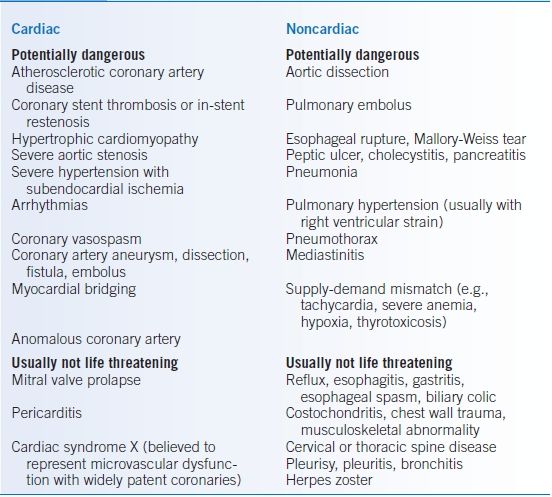

- Physical examination can help identify higher-risk CHD patients or noncardiac causes of chest pain (Table 7-4).

- Concerning physical exam findings include signs of heart failure (edema, rales, S3 heart sound), new or worsening mitral regurgitation murmur, hypotension, and tachycardia or bradycardia.

- Evidence of undiagnosed cardiac risk factors may be noted on examination (e.g., tendon xanthomas in hypercholesterolemia, abnormalities of pulse suggestive of PAD).

- Severe HTN alone may provoke coronary ischemia (hypertensive emergency). In patients with chest discomfort and elevated BP, rapid reduction of systolic BP by approximately one-third—generally in a monitored setting such as an emergency department—with gradual further reduction over the subsequent 48 hours is imperative.

TABLE 7-4 Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

Differential Diagnosis

- The differential diagnosis of chest pain is broad (Table 7-4). The diagnosis of obstructive CAD relies heavily on the history and ECG.

- Ischemia from etiologies other than atherosclerotic CAD

- Subendocardial ischemia related to myocardial strain requires management of the underlying cause of strain (i.e., blood pressure control, β-blockers or calcium channel blockers [CCBs] for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valve replacement for aortic stenosis).

- Variant angina from coronary vasospasm (an uncommon cause of angina, usually associated with ST-segment elevation on the ECG).

- Treatment of spasm using CCBs and/or nitrates should be combined with interventions aimed at endothelial stabilization (e.g., tobacco cessation, aspirin therapy, weight loss and exercise, possibly ACE inhibitors). β-Blockers can worsen variant angina and should be avoided.

- Provocation testing in the catheterization laboratory or 24-hour ECG monitoring to diagnose ST elevations may be necessary for definitive diagnosis.

- Treatment of spasm using CCBs and/or nitrates should be combined with interventions aimed at endothelial stabilization (e.g., tobacco cessation, aspirin therapy, weight loss and exercise, possibly ACE inhibitors). β-Blockers can worsen variant angina and should be avoided.

- Rarely, myocardial bridging (or certain congenital coronary artery anomalies) may also cause angina. This is best relieved by reducing inotropy and improving diastolic flow with β-blockers and possibly CCBs. Surgery for certain coronary anomalies may be necessary.

- Cocaine or other stimulants may provoke ischemia via tachycardia, HTN, and vasoconstriction. Other than cessation of cocaine usage, management is similar to vasospasm, but β-blockers are generally avoided because of the risk of unopposed α-adrenergic stimulation. With acute intoxication, nitrates and benzodiazepines are the mainstay of treatment.

- Subendocardial ischemia related to myocardial strain requires management of the underlying cause of strain (i.e., blood pressure control, β-blockers or calcium channel blockers [CCBs] for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, valve replacement for aortic stenosis).

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratories

To identify precipitating causes of chest pain or assess risk, initial tests should include complete blood count, renal function and electrolytes, lipid panel fasting glucose, and an ECG.

Imaging

- Chest radiography may help identify aortopathies, structural heart disease/heart failure, or pulmonary/skeletal etiologies, which can cause chest discomfort.

- Echocardiography (echo) is indicated when chest symptoms or examination findings are potentially related to structural (e.g., valvular heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, pericardial disease) or functional abnormalities (systolic or diastolic heart failure) with the heart. Echo may also be obtained in patients with prior MI or an abnormal ECG.

Diagnostic Procedures

Stress Testing

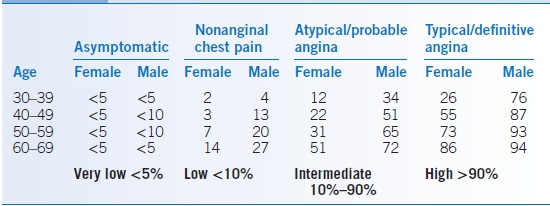

- In patients without established IHD, determining the pretest probability of CAD is very important in deciding which symptomatic patients should undergo stress testing to establish a diagnosis of CAD (Table 7-5).39,41,42

- Stress testing is most clinically useful in patients with symptoms and intermediate pretest probability of CAD (test results will have the least false-positive and false-negative results). Stress testing in low pretest probability patients (<10% likelihood of CAD) will result in more false-positive tests.39,43,44

- Patients with symptoms and high pretest probability of CAD, with severe stable angina (class III/IV despite appropriate medications), and with high-risk unstable angina (stress testing contraindicated) can proceed directly to cardiac catheterization.

- Stress testing is most clinically useful in patients with symptoms and intermediate pretest probability of CAD (test results will have the least false-positive and false-negative results). Stress testing in low pretest probability patients (<10% likelihood of CAD) will result in more false-positive tests.39,43,44

- Other situations where stress testing is indicated include the following:

- Assessing change in angina pattern (low-risk unstable angina) in those with prior coronary revascularization on optimal medical therapy should be accompanied by cardiac imaging.

- Assessing the functional significance of a coronary lesion noted at angiography should be considered with imaging.

- Assessing for an ischemic etiology of a new diagnosis of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction in a patient without ischemic symptoms and not at high risk for CHD should be accompanied with cardiac imaging.

- Assessing for an ischemic etiology/myocardial scar in the setting of ventricular tachycardia in a patient without ischemic symptoms and not at high risk for CHD should be accompanied with cardiac imaging.

- Determining prognosis in patients with known symptomatic IHD or in those without known IHD but are at intermediate or higher likelihood of having CAD but invasive interventions are less desirable (with or without cardiac imaging).

- To assess adequacy of medical therapy for symptomatic patients with CAD in whom ongoing symptoms may not be of ischemic origin.

- Prior to starting cardiac rehabilitation, to assess ischemic burden after an ACS where revascularization was not performed, or in previously sedentary patients planning on embarking on vigorous exercise regimens or as part of an exercise prescription, especially in those at high risk for silent ischemia.

- Preoperatively in some circumstances (see Chapter 2).

- Although some guidelines suggest stress testing in some asymptomatic individuals (e.g., coronary calcium score >400 or airline pilots), we do not recommend stress testing in most asymptomatic individuals.

- Assessing change in angina pattern (low-risk unstable angina) in those with prior coronary revascularization on optimal medical therapy should be accompanied by cardiac imaging.

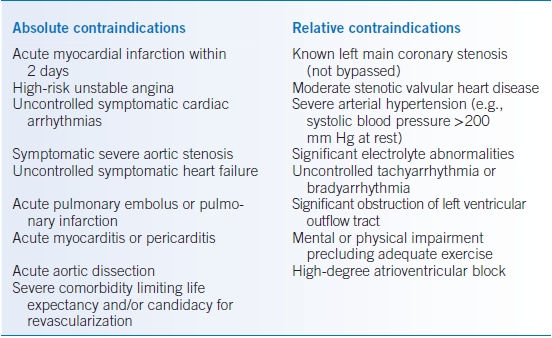

- Contraindications to exercise stress testing are listed in Table 7-6.43

- Generally, β-blockers, nondihydropyridine CCBs, and other antianginals (e.g., nitrates) should be held the day prior to stress testing to permit a normal heart rate/dilatory response in patients without established CAD. In patients with known CAD, these medications may be continued if adequacy of medical therapy is being tested.

TABLE 7-5 Pretest Probability of Coronary Artery Disease on Catheterizationa

Modified from Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2012;129:e354–e471.

TABLE 7-6 Contraindications to Exercise Testing

Modified from Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Beasley JW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for exercise testing: executive summary. Circulation 1997;96:345–354.

Exercise Treadmill Testing

- Exercise treadmill testing (ETT) with or without cardiac imaging is the preferred method of stress testing and should always be attempted unless it is obvious that the patient cannot exercise or other contraindications to ETT are present.

- ST elevation during stress testing localizes myocardial injury and suggests high-grade obstruction of an epicardial coronary artery. These patients are usually referred urgently for cardiac catheterization.

- Inadequate heart rate response (<85% of the maximum predicted heart rate [MPHR]) can render the stress test nondiagnostic. Upsloping ECG changes may also result in an indeterminate test.

- Downsloping or horizontal ST-segment depression is suggestive of ischemia although it does not necessarily localize the coronary lesion with accuracy.45

- A positive test is defined as ≥1 mm of ST depression in two contiguous ECG leads 60 to 80 ms after the J-point when compared with the PR segment.

- Apart from the ECG, the blood pressure response and heart rate response may be clinically useful. Hypertensive responses may require uptitration of blood pressure medications.

- ST elevation during stress testing localizes myocardial injury and suggests high-grade obstruction of an epicardial coronary artery. These patients are usually referred urgently for cardiac catheterization.

- Prognosis is directly related to exercise stress testing functional capacity, degree of exercise-induced angina, severity of ECG changes, and length of time for ECG changes to revert back to normal in recovery.

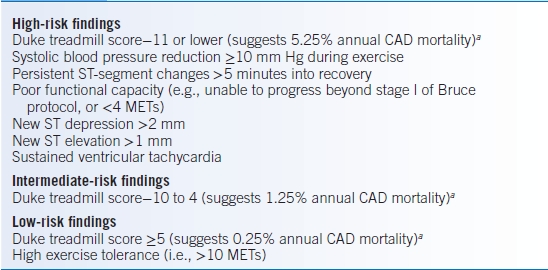

- The Duke treadmill score incorporates several prognostic factors from exercise testing into a simple formula (Table 7-7).46

- High-risk patients should be referred for coronary angiography, whereas intermediate-risk patients may be further stratified by either angiography or a repeat stress test with imaging to better assess ischemia.39

- The Duke treadmill score incorporates several prognostic factors from exercise testing into a simple formula (Table 7-7).46

TABLE 7-7 Duke Treadmill Scorea and Other Prognostic Factors during Exercise Stress Testing

aDuke treadmill score = minutes of exercise on Bruce protocol – (5 × ST deviation in mm) – (4 × exercise angina score). Exercise angina score: 0 = no angina, 1 = angina during the test, 2 = angina causing test termination.

CAD, coronary artery disease; MET, metabolic equivalent.

Data from Mark DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE, et al. Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 1991;325:849–853.

Pharmacologic Stress Testing.

- In patients unable to exercise or attain target heart rate, pharmacologic stress testing should be performed and is always accompanied by cardiac imaging.39

- Pharmacologic stress tests involve redistribution of myocardial blood flow using vasodilators (adenosine or regadenoson) or adrenergic stimulation (dobutamine).

- Adenosine and regadenoson: Adenosine can provoke bronchospasm in patients with severe reactive airway disease. Regadenoson is less likely to cause bronchospasm but should be avoided in these patients. Both agents are contraindicated in advanced AV block, sick sinus syndrome, and those taking oral dipyridamole. All caffeine products need to be withheld for 12 to 18 hours prior to use of these agents since caffeine can block the effect of the vasodilators. Aminophylline can be given to reverse the effects of adenosine or regadenoson.

- Dobutamine may provoke arrhythmias or hypotension and should be avoided in patients with uncontrolled atrial fibrillation, known ventricular tachycardia, or known aortic dissection. β-Blockers can be given to reverse the effects of dobutamine.

- Adenosine and regadenoson: Adenosine can provoke bronchospasm in patients with severe reactive airway disease. Regadenoson is less likely to cause bronchospasm but should be avoided in these patients. Both agents are contraindicated in advanced AV block, sick sinus syndrome, and those taking oral dipyridamole. All caffeine products need to be withheld for 12 to 18 hours prior to use of these agents since caffeine can block the effect of the vasodilators. Aminophylline can be given to reverse the effects of adenosine or regadenoson.

Stress Tests with Imaging.

- Echocardiographic imaging, radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), or cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging can be used as imaging adjunct to stress testing and is recommended if the baseline ECG is abnormal (LV hypertrophy with secondary ST-segment changes, resting ST depression >1 mm, digoxin effects, left bundle branch block [LBBB], ventricular pacemaker beats, preexcitation) or in patients who cannot exercise to an adequate heart rate.39

- When LBBB or electronic ventricular pacing is present, exercise stress testing should be avoided in favor of a pharmacologic stress test to prevent a false-positive study due to septal abnormalities. In all other circumstances where stress testing is ordered, ETT with or without imaging is the stress test of choice.

- Sensitivity and specificity are improved with the addition of cardiac imaging as compared to ETT alone.

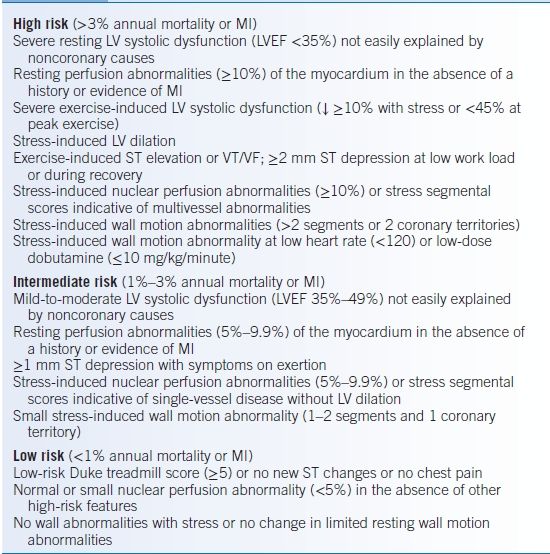

- High-risk findings during stress testing (Table 7-8) should prompt coronary angiography for prognostic assessment and potential revascularization in appropriate candidates.39

- Each stress imaging modality has its own advantages but similar sensitivities and specificities. In general, indications for stress echo and stress MPI are interchangeable; they are both currently preferred over stress CMR.

- Stress echo allows assessment of both cardiac structure and function with higher specificity, lower cost, and no exposure to radiation, but acquisition and interpretation of stress images require expertise by a dedicated sonographer and echocardiographer. Dobutamine is the preferred pharmacologic agent in those who cannot undergo ETT.

- Guidelines permit more liberal use of stress echo in patients with lower likelihood of CAD, as compared to stress MPI, even if they have a normal baseline ECG.

- Stress radionuclide MPI has a high sensitivity for the detection of CAD and is less technically demanding. In patients with severe cardiomyopathies, stress images can be easier to interpret as compared to stress echo. False-negative studies in the presence of left main or triple vessel disease can occur due to balanced ischemia and should be considered when interpreting results. Exposure to nuclear isotopes that require specialized handling and licensing is a disadvantage of radionuclide MPI.

- Stress CMR is currently limited to a few centers that have the necessary expertise to perform and interpret such studies. Advantages of CMR include the ability to look at cardiac structure/function without exposure to radiation. Additionally, viability of cardiac muscle and infiltrative diseases of the heart may also be assessed. Currently, stress CMR can only be performed as a pharmacologic stress test (vasodilator or dobutamine) and hence should generally not be considered in those who can exercise.

- Stress echo allows assessment of both cardiac structure and function with higher specificity, lower cost, and no exposure to radiation, but acquisition and interpretation of stress images require expertise by a dedicated sonographer and echocardiographer. Dobutamine is the preferred pharmacologic agent in those who cannot undergo ETT.

TABLE 7-8 Prognostic Markers from Stress Testing

LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; VT, ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation

Modified from Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2012;129:e354–e471.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree