Should the regulatory submission contain data for a “lean” or “fat” development plan? The terms lean and fat refer to the number of studies conducted in each area of development (e.g., toxicology, medical, preclinical), the number of patients or animals in each study, and the amount of data collected on each patient or animal. The answer to this question is ideally based on a benefit-to-risk assessment for any drug, on special status or need (e.g., an important orphan drug versus a me-too drug), as well as on special regulations that may be utilized [e.g., accelerated approval, Treatment Investigational New Drug Application (IND)]. Because all data available to the company from anywhere in the world must be filed on a new drug for most regulatory authorities, the choice of a fat versus lean plan must be considered at the outset of a new drug’s development. Nonetheless, it is common for a submission to be lean in some aspects and fat in others. Failure to plan a drug’s development internationally at the outset of its development may lead to undesired data being obtained and force a company to adopt a different regulatory strategy than the preferred one.

Table 85.1 Selected functions of regulatory affairs professionals

1.

Ensure compliance of regulatory submissions with relevant regulations.

2.

Ensure compliance of relevant activities and reports with GMP, GLP, and GCP.

3.

Serve as a liaison with one or more regulatory authorities.

4.

Serve as liaison with the headquarters or subsidiaries of the company.

5.

Serve as a member on project teams and guide the direction of various activities using a regulatory perspective.

6.

Attend relevant meetings of regulatory authorities that discuss the company’s drugs.

7.

Attend relevant open meetings of the regulatory authorities discussing competitors’ drugs.

8.

Write letters and telephone regulatory authorities as appropriate to ask or answer questions or to present information.

9.

Follow relevant pharmaceutical news and events through reading professional literature, attending professional meetings, and contacting one’s network.

10.

Help develop and propose a regulatory strategy for the company and for individual drugs.

11.

Maintain records of all regulatory submissions and provide an information retrieval service for company staff.

GMP, Good Manufacturing Practices; GLP, Good Laboratory Practices; GCP, Good Clinical Practices.

Should a single regulatory submission for marketing authorization [e.g., New Drug Application (NDA)] be made for multiple dosage forms, indications or routes of administration, or should a separate regulatory submission be made for each dosage form, indication, or route of administration? The answer to this question is often a matter of senior research and development (R and D) managers trying to second-guess the reviewing policy of a specific regulatory authority as well as marketing managers trying to second-guess the reception

of the drug for each dosage form in the marketplace. Secondguessing the actions of a regulatory authority is seldom possible, despite the most sophisticated reviews of the regulatory affairs staff. A limiting factor is that many companies are unable to co-develop multiple dosage forms or routes of administration simultaneously and submit applications at the same (or nearly the same) time.

Should the initial regulatory submission for marketing authorization (e.g., NDA) be made in the country in which (a) the fastest approval is expected, (b) the least amount of data are required, (c) the largest market exists, or (d) the best opportunity exists to obtain postmarketing data? Alternatively, should the submission be delayed until it is submitted to many countries simultaneously? Most companies, particularly the mid- and large-sized companies, now follow the last approach whenever possible. Nonetheless, regulatory applications in Japan usually follow a few years later for practical reasons.

By submitting a similar dossier with the same data to many countries simultaneously, one avoids the potential problem of having to redo expert reports for new dossiers when additional data are obtained. This could create major problems if different interpretations are reached in different versions of an expert’s report, or in reports written by two or more experts at various times. Within Europe, this is becoming much less of an issue since the CTD was approved in 2000, and also because dossier generally are submitted to all European members of the European Union at one time. For many other countries, the question of resolving differences between submissions still exists; but this issue is less relevant in almost all countries that receive submissions several years after the initial ones are submitted.

Even when a company will use the ICH guidelines and follow the CTD format, there is still a question about how large the core package of data should be. Should it be as small as possible or quite large with many modules that may be used in multiple submissions? A large core package without the ability to separate it into individual modules should be avoided. The question of core size should be addressed at the outset of a new drug’s development. Many of the issues surrounding this question are discussed in Guide to Clinical Trials (Spilker 1991).

Should an electronic submission be made to a regulatory agency, and if so, what part(s) of the application should be submitted electronically? There is a range of possible options for electronic submission, from submitting submissionenabling, word-processing capabilities to be achieved to supplying raw data (plus reports), which enables the regulatory authority to freely explore new analyses. Interactions with the regulatory authority about the type and format of electronic submission [e.g., electronic CTD (e-CTD)] should begin early in the development process. The experience and skills of the regulatory affairs group with electronic submissions varies widely among companies, but the number of electronic submissions is expected to increase, even though adoption has been much slower than anticipated (see Chapter 71).

Should a company proactively interact with a regulatory authority at all stages of the development process, or should it adopt a totally reactive position—only responding to questions from the regulatory authority? The author believes it is particularly important to prepare the regulatory authority to view an application on a novel drug in the way the company believes is most appropriate. Submitting a novel regulatory application without attempting to prepare the mindset of the regulators is likely to lead to delays in its processing and review. In the United States, there are specified times during a drug’s development when it is appropriate to present and discuss data and plans with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These occur usually at the end of Phases 1 and 2 and at the pre-NDA stage, although meetings at other times (e.g., before the filing of an IND) are possible and generally held. The pre-IND meeting for example, may be held shortly prior to its submission or a year or more prior to this submission. The rationale for holding the meeting a long time in advance of submitting the IND is to seek regulatory agency advice on questions the company has about studies it needs to conduct for the IND in the chemistry, manufacturing, and controls or preclinical areas.

Should the company attempt to anticipate all important questions that could be raised about the application and conduct studies to answer them? While this question may seem foolish, there are companies that seek to do this. A balance should be sought between preventing the waste of company resources in attempting to be able to address all important questions and obtaining data to answer the most obvious (and most likely to be asked) questions. No company could ever obtain a sufficient amount of data to be able to address all relevant and important questions by regulatory authorities. Data that address subtle questions about nuances of the drug’s characterization or activity are unlikely to be required prior to the drug’s approval. It is possible to determine the most likely questions to be raised. Collecting data to address these questions is likely to enhance the likelihood of the drug’s approval, even if the data are collected after the application is submitted (but prior to its approval).

How should the company respond to questions from regulatory authorities about a regulatory submission? The company may respond anew to each request for information, and it may have established standard operating procedures for responding to regulatory questions. Major regulatory agency letters requesting data and information can be assigned to a task force or to an individual who can prepare a written response or coordinate the work needed to obtain a response.

Should the regulatory strategies be designed to achieve regulatory success or to achieve commercial success? The former type of strategy focuses on obtaining approvals most rapidly. The latter type involves attempts to achieve the greatest market share by influencing decision leaders, planning symposia, developing an approach to publications, and conducting appropriate clinical trials, including those evaluating quality-of-life and pharmacoeconomic endpoints. Ideally, the regulatory strategies chosen will attain both goals.

considered. Regulatory affairs professionals often act as a liaison between personnel in the company (e.g., medical staff, technical development staff) and regulatory authorities. This coordinating role is crucial because it prevents people in the company independently or semi-independently interacting with regulatory authorities. That approach would undoubtedly lead to major problems if different people said different things to regulatory authorities, or if the statements of different people were understood differently than intended. Regulatory affairs personnel document all interactions with regulators, whether in writing, on the telephone or electronically. Some of the topics frequently discussed with regulatory authorities are listed in Table 85.2 and Table 85.3 and types of documents submitted are listed in Table 85.4.

Table 85.2 Selected topics that may be discussed between a regulatory affairs department and regulatory authorities on an investigational drug’s development or dossier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 85.3 Selected topics that may be discussed between a regulatory affairs department and regulatory authorities on marketed drugs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 85.4 Selected types of documents submitted to regulatory authorities | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 85.5 Selected steps in preparing documents for regulatory submissiona | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

group will regularly report on progress and problems to all major company groups, including the board of directors. Regulatory affairs groups usually are asked to make predictions about when the company can expect to receive regulatory approval of the company’s submissions. Predictions are also requested about questions the various regulatory authorities are likely to raise on a wide variety of topics. A company’s course of regulatory action, marketing plans, and manufacturing plans are usually significantly influenced by these predictions.

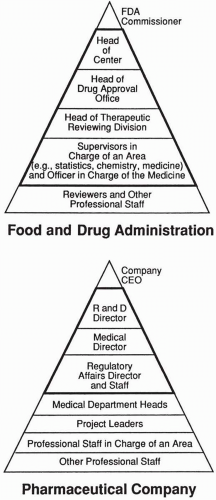

Figure 85.1 Two schematics of the hierarchies within the FDA and a pharmaceutical company. The dark lines encase those individuals who are the primary contacts that interact and liaise with the other hierarchy; however, using a single liaison is desirable. |

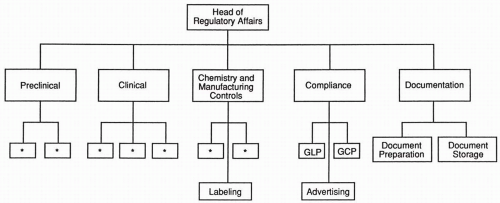

where they interact with other professionals to influence design of studies and quality, quantity, type, data, formats, and general style of reports generated. The specific reports to include in each functional group’s contribution to the regulatory submission are likely to be greatly influenced by regulatory affairs staff.

Preclinical issues

Clinical issues

Chemistry, manufacturing, and controls issues; this group is concerned with coordinating, organizing, and progressing the data on a drug’s chemistry, manufacturing, and quality assurance functions

Preparing documents for inclusion in regulatory submission, including many varied functions required to collect, edit, paginate, index, cross-reference, copy, bind, and distribute documents; while these activities could be conducted manually,

current practice in most companies involves sophisticated computer systems to track reports and to operate other parts of this system.

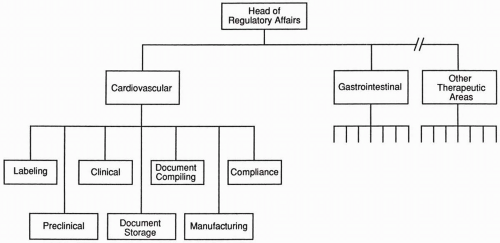

Figure 85.3 Regulatory affairs organizational chart for a group organized primarily by therapeutic area.

Regulatory compliance is an auditing function for ensuring that Good Clinical Practices and Good Laboratory Practices are in compliance; this includes preparing sites in advance of regulatory authority inspection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree