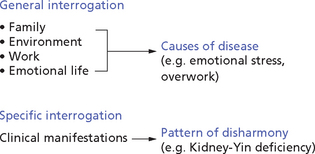

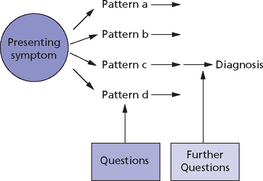

Chapter 28 NATURE OF DIAGNOSIS BY INTERROGATION NATURE OF “SYMPTOMS” IN CHINESE MEDICINE THE ART OF INTERROGATION: ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS TERMINOLOGY PROBLEMS IN INTERROGATION PITFALLS TO AVOID IN INTERROGATION INTEGRATION OF INTERROGATION WITH OBSERVATION IDENTIFICATION OF PATTERNS AND INTERROGATION TONGUE AND PULSE DIAGNOSIS: INTEGRATION WITH INTERROGATION We can distinguish two aspects to the interrogation: a general one and a specific one. In a general sense, the interrogation is the talk between doctor and patient to find out how the presenting problem arose, the living and working conditions of the patient and the emotional and family environment. The aim of an investigation of these aspects of the patient’s life is ultimately to find the cause or causes of the disease rather than to identify the pattern; finding the causes of the disease is important in order for the patient and doctor to work together to try to eliminate or minimize such causes (Fig. 28.1). How to find the cause of disease is discussed in Chapter 48. Box 28.1 summarizes these aspects of interrogation. It is important not to blur the distinction between these two aspects of interrogation; enquiring about the patient’s family situation, environment, work and relationships gives us an idea of the cause, not the pattern of the disharmony. Knowing that a patient is a business man with a heavy work burden, an antagonistic relationship with his employers or marital problems does not tell us which might be the prevailing pattern of disharmony but simply that stress and emotional tension are likely to be the cause of the disharmony; this knowledge is essential when working with the patient to try to eliminate or minimize the causes of disease. Diagnosis by interrogation is based on the fundamental principle that symptoms and signs reflect the condition of the Internal Organs and channels. The concept of symptoms and signs in Chinese medicine is broader than in Western medicine. Whilst Western medicine mostly takes into account symptoms and signs as subjective and objective manifestations of a disease, Chinese medicine takes into account many different manifestations as parts of a whole picture, many of them not related to an actual disease process. Chinese medicine uses not only “symptoms and signs” as such but many other manifestations to form a picture of the disharmony present in a particular person. Thus, the interrogation extends well beyond the “symptoms and signs” pertaining to the presenting complaint. For example, if a patient presents with epigastric pain as the chief complaint, a Western doctor would enquire about the symptoms strictly relevant to that complaint (e.g. Is the pain better or worse after eating? Does the pain come immediately after eating or two hours later? Is there regurgitation of food? etc.). A Chinese doctor would ask similar questions but many others too, such as “Are you thirsty?”, “Do you have a bitter taste in your mouth?”, “Do you feel tired?”, etc. Many of the so-called symptoms and signs of Chinese medicine would not be considered as such in Western medicine. For example, absence of thirst (which confirms a Cold condition), inability to make decisions (which points to a deficiency of the Gall-Bladder), dislike of speaking (which indicates a deficiency of the Lungs), propensity to outbursts of anger (which confirms the rising of Liver-Yang or Liver-Fire), desire to lie down (which indicates a weakness of the Spleen), dull appearance of the eyes (which points to a disturbance of the Mind and emotional problems), deep midline crack on the tongue (which is a sign of propensity to deep emotional problems), and so on. Whenever I refer to “symptoms and signs” (which I shall also call “clinical manifestations”), it will be in the above context. For example, a patient may present with chronic headaches and, even at this very early stage, we are already making a hypothesis about the possible pattern of disharmony on the basis of our experience and our knowledge, that is, we are thinking of Liver-Yang rising because we know it is by far the most common cause of chronic headaches. We therefore ask questions about the character and location of the pain: if the patient says that the pain is throbbing and is located on the temples, even these few details would almost certainly confirm the diagnosis of Liver-Yang rising. However, we should never stop there and reach premature conclusions. Instead we should ask further questions to confirm or exclude the existence of other patterns which also cause headaches. For example, Phlegm is another common cause of chronic headaches and we therefore ask this patient first about other characteristics of the headaches which may confirm Phlegm, and also about possible symptoms of Phlegm in other parts of the body: “Does the patient experience a feeling of muzziness in the head?” “Is the headache sometimes dull and accompanied by a feeling of heaviness?” If the answer to these questions is affirmative, we conclude that Phlegm might be a further cause of the headaches. We then ask other questions related to Phlegm in other parts of the body; in this particular case, we might ask whether the patient occasionally expectorates sputum or sometimes experiences a feeling of oppression in the chest. (Fig. 28.2). The translation from Chinese of the terms related to certain symptoms may also present some problems. The traditional terms are rich with meaning and sometimes very poetic and are more or less impossible to translate properly because Western language cannot convey all the nuances intrinsic in a Chinese character. For example, I translate the word Men as a “feeling of oppression”; an analysis of the Chinese character, however, which portrays a heart squashed by a door, conveys the feeling of oppression in a rich, metaphorical way. What cannot be adequately translated is the cultural use of this term in China often to imply that the person is rather “depressed” (as we intend this term in the West) from emotional problems. As Chinese patients seldom admit openly to being “depressed”, they will often say they experience a feeling of Men in the chest. The specific interrogation (as defined above), based on questions that concern the patient’s clinical manifestations, is aimed at finding the pattern of disharmony; the general interrogation (about the patient’s lifestyle, family situation, emotional environment, living conditions, etc.) is aimed at finding the cause of disease. It would be wrong to confuse the two and to deduce the pattern of disharmony from the enquiry about the patient’s lifestyle, work and family life. I have noticed this occurring in practice many times when a student or practitioner brings a patient to me for a second opinion: I frequently hear comments such as “Andrew is under a lot of stress at work and he therefore suffers from Liver-Qi stagnation”. This is an example of how a practitioner may confuse the general enquiry about the patient’s life to find the cause of the disease with the specific enquiry about clinical manifestations to find the pattern of disharmony. In other words, to go back to the above example, it would be totally wrong to assume that Andrew suffers from Liver-Qi stagnation on the basis of an enquiry about his lifestyle, work, etc.: such a diagnosis can be made only on the basis of a specific enquiry about his clinical manifestations. Patients might well have a lot of stress in their life, but this does not necessarily cause Liver-Qi stagnation as emotional strain may cause many other patterns. Another possible pitfall is to make a diagnosis of a pattern of disharmony on the basis of vague and woolly concepts deduced from observation of the patient’s lifestyle – for example, “Betty seems to be a very “woody” person, so I thought there was Liver-Qi stagnation”. Of course, a diagnosis of a person’s prevailing Element on the basis of the body shape, mannerism, gait and voice is important (see Chapter 1), but this does not always coincide with the prevailing pattern; in other words, a Wood-type person will not necessarily suffer from a Liver pattern of disharmony. Box 28.2 summarizes pitfalls in interrogation.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

NATURE OF DIAGNOSIS BY INTERROGATION

NATURE OF “SYMPTOMS” IN CHINESE MEDICINE

THE ART OF INTERROGATION: ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS

TERMINOLOGY PROBLEMS IN INTERROGATION

PITFALLS TO AVOID IN INTERROGATION

INTRODUCTION