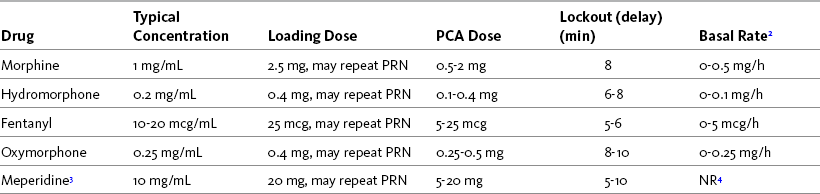

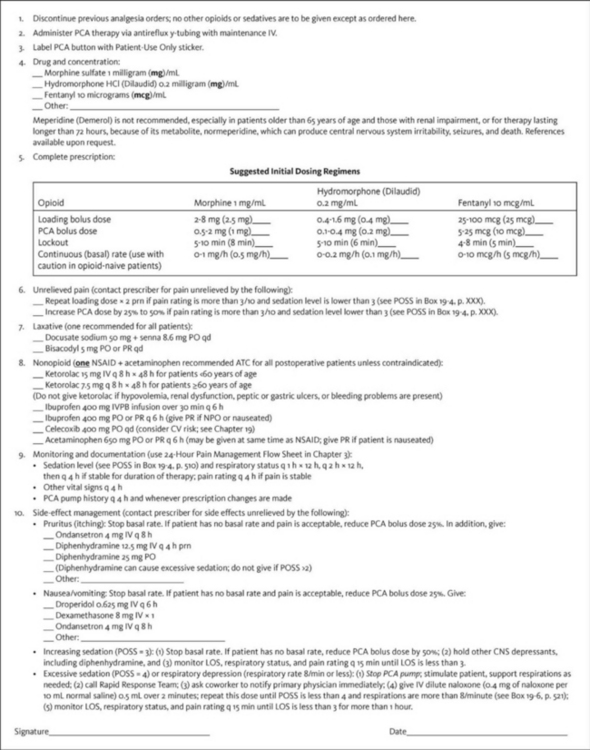

Chapter 17 Initial Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA) Prescription Bolus Dose and Lockout Interval Continuous Infusion (Basal Rate) PCA in Opioid-Tolerant Patients Initiating PCA in the Postanaesthesia Care Unit and Patient Transfer to the Clinical Unit Authorized Agent-Controlled Analgesia Operator Errors: Misprogramming Analgesic Infusion Pumps Infusion Solution and Tubing Changes Tapering and Cessation of Parenteral Analgesia PCA pumps are used to administer opioids by the SC, IV, and epidural routes. Their use requires prescribing a number of parameters (Box 17-1), many of which are safety features to help prevent overdosing; however, it is important for clinicians to appreciate that the safety of PCA depends on appropriate patient selection, initial and ongoing patient/family and staff teaching and goal setting, patient-only use, systematic assessment of responses, and adjustments in therapy as needed (Macintyre, Coldrey, 2009). The reader is referred to an in-depth discussion and comparison of the various analgesic infusion devices used to administer PCA in Sherman, B., Enu, I., & Sinatra, R. S. (2009). Patient-controlled analgesia devices and analgesic infusion pumps. In R. S. Sinatra, O. A. de Leon-Casasola, B. Ginsberg, et al. (Eds.), Acute pain management, Cambridge, NY, Cambridge University Press. Included are desirable pump features and general purchasing considerations. The focus of this chapter is primarily on the clinical use of IV PCA. See Chapter 12 for the underlying principles and research on the efficacy of PCA, Chapter 15 for epidural patient-controlled analgesia (PCEA), and Section V for PCRA. The starting prescription for IV PCA in an opioid-tolerant patient is based on the patient’s current total daily opioid dose. If the patient is switched from one opioid or route to another, this initial prescription is an estimate and must be adjusted according to the patient’s pain and adverse effect profile. The starting PCA prescription for an opioid-naive patient is also just an estimate of a patient’s opioid requirement and must be titrated on the basis of patient response. Table 17-1 provides guidelines for selecting an initial IV PCA prescription for opioid-naive patients and Form 17-1 provides an example of a PCA order set. See an example of a patient information brochure about IV PCA on pp. 544-545 at the end of Section IV. Form 17-1 Example Order Set: Opioid-Naïve Adult IV PCA There is no consensus about whether hour limits should be used. Those who choose not to use them do so because they think patients should have access to as much opioid as they need to manage their pain, restricted only by the amount of the dose and the length of the lockout interval. Those who choose to use an hour limit do so because they think it offers an additional safeguard against overdosing; however, this thinking may provide false reassurance; the only built-in safeguard of PCA is patient-only use (see discussion of PCA by proxy later in this chapter). A benefit of programming an hour limit is that it alerts caregivers that increased doses might be necessary. Hour limits seem to be used more commonly in opioid-naïve than in opioid-tolerant patients. If used, a 1-hour limit is preferable to a 4-hour limit for at least two reasons: (1) caregivers are alerted to the need for an increase in the opioid dose sooner (i.e., within 1 hour instead of within 4 hours); and (2) it eliminates a scenario in which an increase in dose is neglected in patients who use the 4-hour amount in less than 4 hours (i.e., a patient who uses the 4-hour amount in 2 hours and is left for 2 hours without analgesia). In an analysis of data submitted to MEDMARX and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Medication Errors Reporting Program between 1998 and 2003, the USP identified this scenario as a common PCA-related underdosing error (USP, 2004). It is essential that the hour limit be adjusted up or down as necessary on the basis of patient response. If used, the APS (2003) recommends that the hour limit be set at 3 to 5 times the projected hourly IV requirement for at least the first 24 hours.

Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Initial Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)Prescription

CNS, Central nervous system; CV, cardiovascular; hs, at sleep; IV, intravenous; IVPB, IV piggyback; LOS, level of sedation; PO, oral; POSS, Pasero Opioid-Induced Sedation Scale; PR, per rectum; PRN, as needed; q, every. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 464, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Hour Limit

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree