Intrahepatic Biliary-Enteric Anastomosis

Reid B. Adams

Victor Zaydfudim

DEFINITION

Intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomosis is defined as biliary reconstruction at the level of the hepatic hilum (biliary confluence) or more proximal bile ducts.

Intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomoses are indicated for definitive treatment of hilar biliary strictures; rarely, they may be indicated for palliation of malignant hilar obstruction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Biliary strictures at the hepatic hilum can be due to benign or malignant processes. Common malignant etiologies include hilar cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma; benign strictures typically are a result of prior biliary tract surgery or intervention.

Uncommon benign etiologies include inflammatory or autoimmune diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or IgG4 immune-mediated sclerosis.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The most common presentation is jaundice. Associated symptoms may include pruritus, cholangitis, or less commonly, pain. If the patient has had biliary surgery, they may present with an acute abdomen or sepsis due to a biloma or biliary fistula.

In the absence of prior biliary surgery, stone disease should be suspected.

If a history of prior biliary surgery or instrumentation is present, a benign stricture should be suspected. Postoperative strictures present within the first 6 months in approximately 70% of patients. However, benign strictures can present years after biliary surgery.

In the absence of stone disease and prior biliary surgery, a malignant stricture should be suspected.

A complete history and physical examination is required to ensure the patient does not have evidence of infection or symptoms suggestive of metastatic disease. This assessment also should assess whether the patient is a candidate for major surgery.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A fundamental knowledge of biliary anatomy and the adjacent vascular structures is critical for success, both in deciding whether operative intervention is indicated, and if so, the type of procedure and an approach to ensure it is safe and effective. Biliary anomalies are frequent and should be expected; imaging studies should clearly define these structures and their relationship to each other. Hepatic vasculobiliary anatomic details are reviewed in Part 3, Chapter 15, Surgical Anatomy.

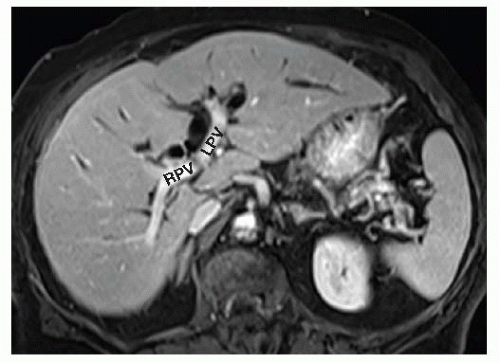

The aim of the diagnostic evaluation is to define the anatomy for restoration of biliary-enteric continuity in patients with benign strictures or plan appropriate palliative care in patients with malignant disease not amenable to curative resection. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is the initial diagnostic study of choice in patients with obstructive jaundice thought to be due to stone disease. Otherwise, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intravenous contrast and MRCP is the initial study of choice for patients with obstructive jaundice due to a stricture (FIG 1). Ideally, it should be performed prior to any biliary interventions such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC). However, most patients come for referral with prior invasive studies or biliary stents in place; these can make image interpretation challenging and/or lead to cholangitis in obstructed segments.

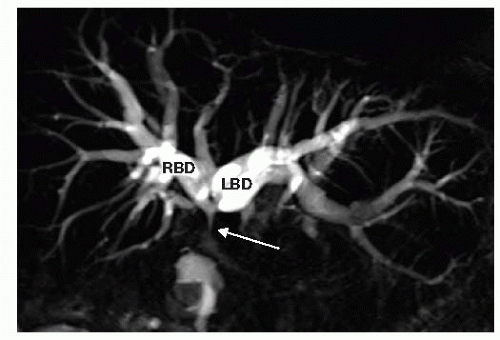

MRI/MRCP gives a detailed view of the biliary tract and the level or type of obstruction when a stricture is the cause (FIG 2). The vascular phases allow assessment of hepatic artery and portal vein involvement in the case of malignant processes and whether the hepatic arteries are intact and patent in cases of benign strictures related to prior biliary surgery. Finally, it allows for the assessment of direct hepatic involvement or metastatic disease.

When contrast for MRI cannot be given or the vascular anatomy is not adequately assessed, B-mode and Doppler ultrasonography (US) is highly accurate in assessing vascular patency and/or involvement.1,2 It is important to note whether lobar atrophy is present, as this dictates treatment options.

ERC and PTC are supplementary techniques for defining the anatomy of the biliary tract and the extent of a stricture

when these are not clear from the MRCP. Either or both may be used to obtain a tissue diagnosis in unresectable patients or for stent placement to treat symptoms and/or for preoperative preparation. There is considerable debate as to which technique is optimal for treating hilar biliary strictures and this discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

FIG 1 MRI during the portal venous phase showing the right portal vein (RPV) and left portal vein (LPV). The dilated left hepatic duct (LHD) lies anterior and superior to the LPV.

FIG 2 This MRCP shows a dilated right biliary duct (RBD) and left biliary duct (LBD), leading to a type II hilar stricture at the proximal most common hepatic duct (white arrow).

To effectively relieve jaundice, approximately 30% of the functioning liver volume must be drained.3 The functioning and proposed drained volumes can be estimated using calculated liver volumes from preoperative cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography [CT] or MRI).4 Conversely, drainage of an atrophied hepatic lobe or segment is not effective.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Issues associated with repair of benign strictures are discussed separately from malignant strictures.

Intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomoses are complex procedures that require experienced, multidisciplinary, hepatobiliary team care. If this is not available at your institution, the patient should be referred to an appropriate institution for definitive repair.

All procedures are done with 2.5× magnification using loupes. This allows for meticulous surgical technique and allows precise dissection and reconstruction.

It is important to establish a standardize approach for biliary-enteric anastomoses. Use this each time and the high intrahepatic anastomosis will be easier to perform.

Preoperative Planning

Benign Stricture

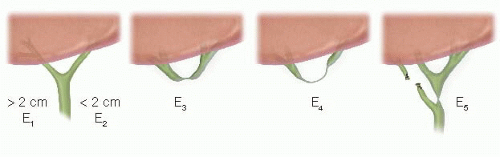

The goal for benign strictures is definitive restoration of biliary-enteric continuity. The type of stricture will dictate the nature of the biliary-enteric anastomosis (FIG 3).5 Types E1 to E3 strictures are amenable to a Hepp-Couinaud approach.6 E4 and E5 strictures require a modified Hepp-Couinaud approach and generally two separate anastomoses to reconstruct the right and left ducts separately.7

Prior to undertaking surgery, sepsis and biliary fistulae must be resolved and all the biliary segments drained. Biliary drainage usually requires a PTC for hilar (high) strictures or injuries.

In the clinical setting of sepsis, operative repair should not be undertaken until a minimum of 6 to 12 weeks have passed. This waiting period allows for resolution of active inflammation and evolution of any ischemic injury. Both of these are critical issues, as repair prior to resolution of these processes will decrease the success of the repair.

Prior to operative repair, each isolated segment of the biliary system ideally should have a PTC placed. Just prior to surgical repair, the PTC drain(s) is exchanged such that the tip is guided into the distal most part of the intubated duct(s) to intraoperatively facilitate localization.

Malignant Stricture

For this group, the preoperative evaluation focuses on whether the patient is a candidate for potentially curative resection. If so, they are approached as outlined in Part 3, Chapter 11.

With unresectable disease, current percutaneous and endoscopic techniques (drainage with plastic or expandable metallic stents and intraductal photodynamic therapy or radiofrequency ablation) provide excellent palliation; thus, there is little to no role for a planned palliative intrahepatic biliary-enteric bypass.

Consequently, intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomosis generally is reserved for patients with biliary obstruction found to be unresectable at the time of exploration and who are expected to survive more than 6 months. Otherwise, the morbidity and mortality associated with bypass is not justified. For instance, patients with unresectable gallbladder carcinoma have a median survival of 20 weeks. Thus, stenting is a better choice for palliation. On the other hand, the median survival for unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma is 52 weeks and a bypass may be reasonable under these circumstances.8 Even this circumstance is questionable, as there appears to be no survival advantage between surgical and

nonsurgical drainage approaches and the morbidity and mortality for surgical approaches are significant in comparison.9

Other intrahepatic biliary-enteric anastomotic approaches are not included in this discussion as they are primarily of historical interest. These include the Longmire approach, mucosal graft operation, and right duct approaches. Current alternatives provide better palliation with lower risks.

This discussion, therefore, is limited to the segment 3 bypass (round ligament or ligamentum teres approach) as the primary practical option for these patients. Although a right sectorial duct bypass can be done, the circumstances where it might be applicable are quite limited and the results relatively poor.8 As such, it has little practical value and the best palliation for these patients is stenting and possibly tumor ablation to prevent liver failure and cholangitis.

Patients eligible for a segment 3 bypass are limited to those with unresectable Bismuth types I, II, or IIIa strictures without atrophy of the left hepatic lobe; to be effective, at least 30% of the functioning liver volume must be drained. Types IIIb and IV lesions are not effectively drained by a segment 3 approach. Importantly, there is no role for this bypass if the right ductal system has been contaminated by prior right duct intubation, as these patients will require continued right duct drainage to prevent cholangitis.

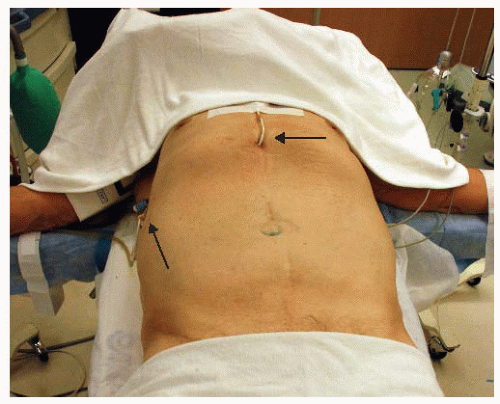

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position with both arms extended (FIG 4).

The percutaneous drains are aseptically prepped but positioned out of the field as much as possible (i.e., under additional sterile draping) and ideally left to drain. The catheters will need freedom of movement from within the abdominal cavity during the procedure, thus, extreme care must be taken to ensure that this is feasible without undue risk of inadvertent dislodgement of the drains.

TECHNIQUES

HILAR HEPATICOJEJUNOSTOMY (HEPP-COUINAUD APPROACH)

Preparation

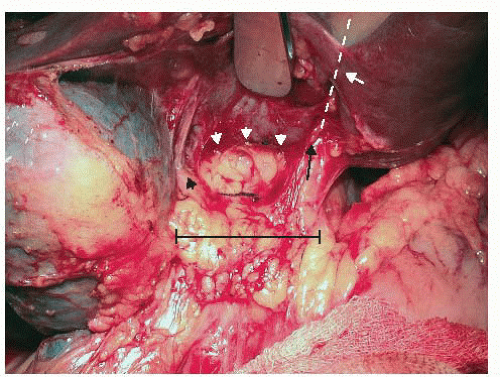

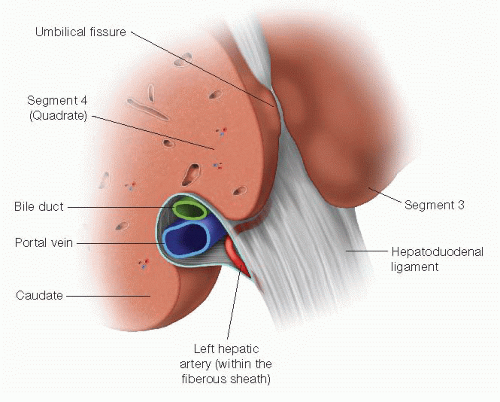

This approach takes advantage of the extrahepatic course of the left hepatic duct as it runs along the base of segment 4 for approximately 2 to 3 cm from the biliary confluence to the umbilical fissure (FIG 5). It is the anterior-superior most structure in the hilum, and this position facilitates its exposure and the anastomosis while minimizing injury to the portal vein and hepatic artery (FIGS 6 and 7).

Incision

A right subcostal incision allows access to the hepatic hilum. Often, a midline extension facilitates full exposure (FIG 8).

Exposure

Identify, doubly clamp, and divide the falciform ligament. Ligate each end and leave a long tie on the superior side to use as a handle. Divide the falciform ligament superiorly to the superior edge (diaphragm) of the liver. When the patient has extensive adhesions, the ligamentum teres is an invaluable guide to locating

the umbilical fissure. During dissection, follow it posteriorly to locate the umbilical fissure; this assists in identifying the anterior surface of the hepatoduodenal ligament.

Take down adhesions to the inferior surface of the liver and the anterior surface of the hepatoduodenal ligament to expose the gallbladder fossa and the base of segment 4 (FIG 9). It is easiest to work from the right edge of the liver back toward the hilum when taking down adhesions. There often is a free space at the right edge of the liver that allows access posteriorly around the lateral edge of the adhesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree