Interactions between Clinicians and Statisticians for Analysis and Interpretation of Clinical Data

The most difficult thing is not to fool yourself, because you are the easiest one to fool.

–Richard P. Feynman, US Nobel Prize winner in Physics.

If I have ever made any valuable discoveries, it has been owing more to patient attention, than to any other talent.

–Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

The ideal approach both for planning a clinical trial and for analyzing and interpreting clinical data after the trial is completed is for the clinician to form a partnership to collaborate with a statistician.

BACKGROUND

Several decades ago, statisticians who viewed the field of medical trials saw that it was a field that used imprecise and often inappropriate methods for designing trials, analyzing data, and interpreting results. They proposed new and modified methodologies that were implemented by the clinicians to raise standards of clinical study designs. Their contributions to this field are extremely important and form a major part of the foundation of modern clinical trials.

It is a basic principle that statisticians can statistically interpret clinical data. That is a clear and unarguable point. However, some statisticians suggest that their role in clinical trials includes the clinical interpretation of clinical data as well as its analysis and statistical interpretation. One possible reason that some statisticians believe they are qualified to provide clinical interpretations of data appears to be their acknowledged expertise with numbers and their ability to analyze numbers in many ways, combined with the fact that clinical interpretations are based primarily on the clinical data analyses that the statistician has made. However, the author does not believe that most statisticians are prepared by training or by experience to clinically interpret clinical data, even though they may interpret their statistical analyses of clinical data from a statistical perspective.

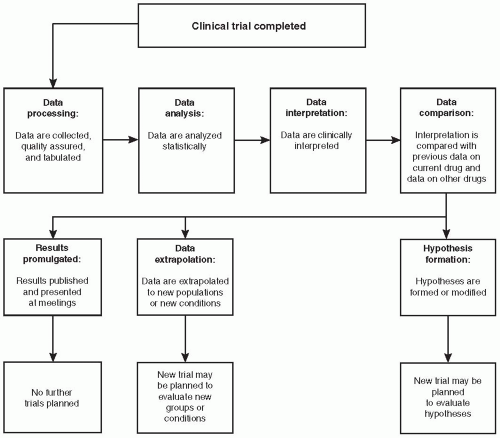

Figure 78.1 Procedures to conduct after a clinical trial is completed. The initiation of data processing often occurs while the trial is still in progress. |

The clinical interpretation of data by statisticians has been claimed to be part of their role by some statisticians and is found in various books and chapters on clinical trial methods written by statisticians. For example, Moses (1985) defined the field of statistics as referring “to the aspects of interpreting quantitative data that tend to be independent of the specific data at hand and thus to carry over from one problem to another.” A.A. Nelson (1980) stated, “Statistics are the tools with which one analyzes and interprets research data to develop scientific theories.” Although it is possible that these authors were referring to only statistical interpretations, the context of their comments in clinical journals suggests that they included the possibility of statisticians making clinical interpretations as well. A scientifically and medically accurate and appropriate approach to the process of data analysis and interpretation is described in this chapter.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR DATA ANALYSIS AND DATA INTERPRETATION

The two processes of statistical analysis/interpretation and clinical interpretation of data from a clinical trial are separate functions, although both processes are related, and both are required to fully understand the results (Fig. 78.1). The primary role of statisticians is to both help design a clinical trial and to analyze and statistically interpret the data after a trial is completed and the data have been entered into computers and presented in tables, figures, and listings that the statistician has previously determined would be created [in the statistical analysis plan (SAP)]. Most statisticians prefer to have the clinician involved with this SAP or, at the minimum, to review it after it is in draft form. It is the role of trained and experienced clinicians to develop a medical interpretation of the data. This usually requires using a statistical report of the analyses, assuming that one has been written. The clinical interpretation is largely based on the statistical analyses and to a variable degree on other analyses or data (e.g., pathology reports, toxicology reports, analytical chemistry reports). There are exceptions to this principle if, for example, a proof-of-concept trial (e.g., a pilot trial) is conducted using a much smaller number of patients than the number required to have 80% or greater power of finding an effect if it is present or, alternatively, if no power analysis has been done and clinical judgment was used to decide on the number of patients to include in the trial. In those situations, the clinical interpretation of the data will not be based on a statistical analysis of the results and none may have been conducted. (Nonetheless, the statistician may still make a contribution to understanding what the data mean.) The number of patients might have been chosen based on the number believed by the clinician(s) involved with the

trial’s design to provide some assurances of finding a clinically significant effect if one was present or to answer another question. This approach is based on the belief that good data in a well-designed and well-controlled clinical trial are better than a much larger amount of mediocre data from a larger number of patients in a poorly designed trial (e.g., open label or single blind).

trial’s design to provide some assurances of finding a clinically significant effect if one was present or to answer another question. This approach is based on the belief that good data in a well-designed and well-controlled clinical trial are better than a much larger amount of mediocre data from a larger number of patients in a poorly designed trial (e.g., open label or single blind).

Statisticians are generally asked to review and critique clinical interpretations. Statisticians commonly suggest ideas or modifications for the clinician(s) to evaluate. When data and results of a trial are extrapolated to new patient groups or new clinical hypotheses are created, the processes of extrapolation and hypothesis generation are also primarily roles of clinicians.

Why Physicians Interpret Data and Clinical Trial Results

There are several reasons why it is important that the clinical interpretations of clinical data be made by well-qualified physicians. First, professionals of any type who are not well trained in clinical trial methodologies, clinical science, and sometimes clinical practice do not usually have a sufficient background to understand the data fully. Second, there is no reason to believe that a person who fully understands the analyses of numbers from a trial also fully understands their implications, particularly in certain disease areas with which he or she may not be familiar. If statisticians were to clinically interpret the data, it is possible that this would be done by adhering to statistical principles. This approach would be insufficient because most clinical interpretations require clinical knowledge of specific diseases and situations that are not achieved through textbooks and courses. This understanding requires learning that comes from treating patients. Clinical expertise and hands-on experience often lead knowledgeable physicians to negate what might appear to be a reasonable interpretation based primarily on logic, common sense, and/or statistical reasoning. In addition to knowledge of a disease, a sound interpretation of clinical data requires knowledge of clinically oriented biases and confounding factors that may be present and unknown to statisticians. It also goes without saying that many, if not most, clinicians are not fully experienced in the realm of statistics, at least in more advanced and sophisticated statistics.

An important issue that sometimes arises in the analysis of data from a clinical trial involves the confusion of statistical and clinical significance. This potential confusion of statistical and clinical significance may relate to interpretation of efficacy, safety, demographic, or any other type of clinical data. World-class clinicians or statisticians may fail to understand the significance of the data because they are focusing on their own discipline and are unaware of all of the implications of the other. This is discussed further in Chapter 76.

Can Statisticians Clinically Interpret Clinical Trial Data?

Numerous professionals are trained in both medicine and statistics and are fully capable of using both sets of tools and processes to both analyze and interpret data. A statistician who does not have formal training and experience in medicine is generally unable to reach adequate interpretations of the data. Likewise, without formal training, a clinician is not an expert in statistical designs and analyses. Nonetheless, even when a single individual is both an experienced clinician and statistician, he or she performs the processes of data analysis and data interpretation separately and sequentially. Data analysis is conducted prior to interpretation, even if the time that elapses between analyzing and interpreting the data is minimal or almost nonexistent.

Can Nonphysician Scientists Interpret Clinical Trial Data?

While a large majority of physicians should be able to interpret clinical data, only a minority of nonphysicians who are clinical scientists are able and qualified to interpret clinical data. If the clinical training and experience of nonphysician clinical scientists are adequate, then they may be able to interpret clinical data. One caveat relates to the limited clinical understanding that most nonphysicians have of patients and medicine, even if they are “clinical” scientists. Quite frankly, these people will be unlikely to have treated patients and had responsibility for their care, even if they have worked inside a hospital or clinic for many years.

The difference that may be difficult for those people to understand is analogous to the belief that many academic physicians have that they understand drug development because they have been investigators on several or even many clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. Those professionals inside the industry who are experts in drug development can appreciate the naiveté of those academicians, and physicians can likewise appreciate the naiveté of PhD scientists working in industry who believe they can fully interpret clinical data without at least some physician input.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree