KEY TERMS

Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC)

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA)

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)

Years of Potential life lost (YPLL)

Injuries are the fourth leading cause of death in the United States.1(Table 20) They are even more important than statistics suggest because injuries disproportionately affect young people and thus cause many years of potential life lost (YPLL). Injuries are the number one cause of death among people ages 1 to 44.1(Table 21) In addition to the people killed by injuries, there are almost as many survivors left with permanent disabilities, a major economic and emotional drain on families and on society in general.

Traditionally, injuries have been thought of as “accidents,” unavoidable random occurrences, or the results of antisocial or incautious behavior. It is only recently that public health practitioners have recognized that injuries can and should be treated as a public health problem, analyzable by epidemiologic methods and amenable to preventive interventions. While most injuries are caused to some extent by individual behavior, they are also influenced by the physical and social environment. Public health programs to prevent injury must find ways to change people’s behavior by the classic methods of education and regulation, but for many types of injuries, prevention by changing the environment may be more effective.

Epidemiology of Injuries

Prevention of injury, like the prevention of most diseases, is based on epidemiology. Data are needed to answer the questions of who, where, when, and how, looking for patterns and connections that suggest where the greatest needs for prevention are as well as ways to intervene to prevent the injury. Fatal injuries are generally categorized as unintentional (sometimes referred to as “accidental”) or intentional (homicide or suicide).

Injuries are an especially important cause of death in young people. In 2010, unintentional injuries caused 32 percent of deaths in children aged 1 to 4, 31 percent of deaths in children aged 5 to 14, and 42 percent of deaths in young people aged 15 to 24.1(Table 23) An additional 31 percent of deaths in the 15 to 24 age group were caused by suicide or homicide.

Race and gender affect injury rates. Males are more likely to sustain injuries than females, with a fatal injury rate 1.7 times higher than that of females for all age groups combined. Blacks have lower rates of injury mortality than whites, except for the high rates of homicide among young black males, which is more than nine times the rate for white youths.1(Table 32)

Injury rates, like other indicators of poor health, are higher in groups of lower socioeconomic status. The death rate from unintentional injury is twice as high in low-income areas as in high-income areas. House fires, pedestrian fatalities, and homicides are all more common among the poor.2 The poor are more likely to have high-risk jobs, low-quality housing, older, defective cars, and such hazardous products as space heaters, all of which contribute to higher injury risks.

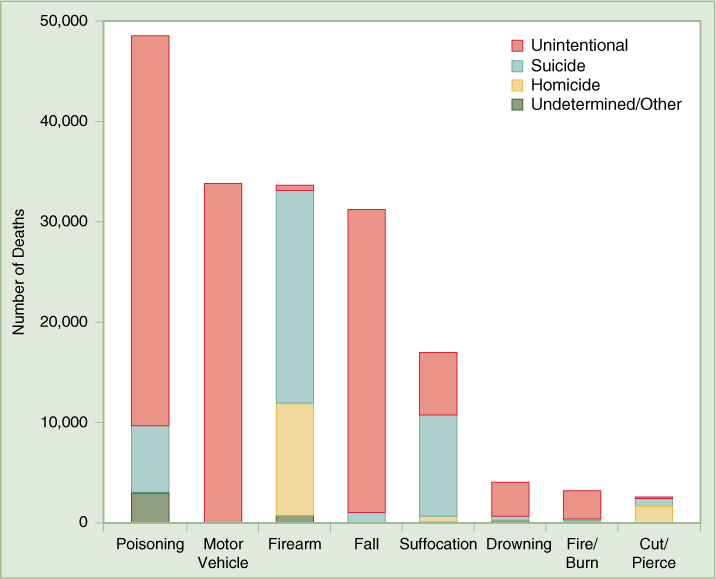

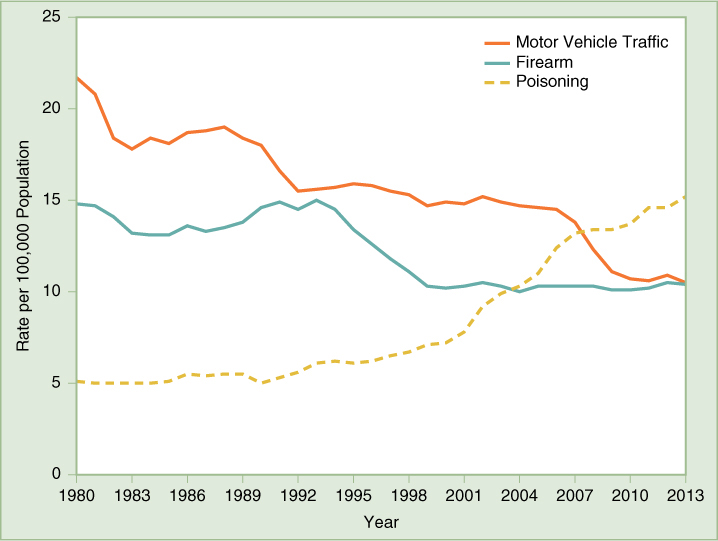

(FIGURE 17-1) shows the leading categories of injury deaths in the United States. Poisoning leads the list, followed by motor vehicle injuries, with firearms fatalities third. As a result of the high priority the federal government has placed on prevention of motor vehicle–related injuries, as described in a following section, highway fatalities have declined over most of the past four decades. Firearm fatalities increased between 1968 and 1994, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) predicted that if trends continued, the number of firearm-related deaths would surpass those related to motor vehicles by the year 2003.3 The trend in firearm injuries reversed in the early 1990s, however, while traffic fatalities remained steady, and then fell in the early 2000s so that the two causes are now about equal in the injury statistics, as shown in (FIGURE 17-2).4

Death rates from poisoning overtook traffic fatalities in 2009, however, becoming the leading cause of injury death in the United States. Deaths due to prescription drugs quadrupled between 1999 and 2010.5 Other major causes of injury deaths that have drawn significant public health attention are falls and jumps, suffocation, drowning, and fires and hot objects.

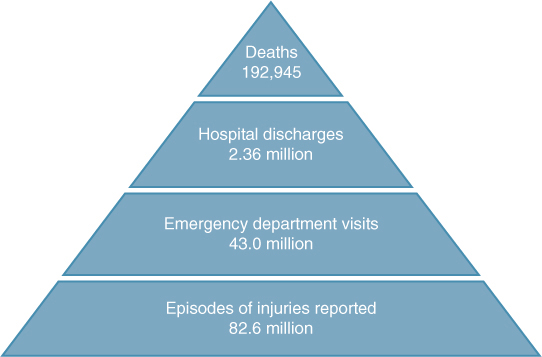

Many injuries are not fatal, of course, but fatal injuries are the ones that are most reliably reported. While data on nonfatal injuries are less complete, these injuries can have serious and even devastating effects. In the years 2010–2013, for every fatal injury reported, more than 12 individuals were hospitalized for nonfatal injuries, and 223 were treated in the emergency department.6 These numbers are illustrated in the “injury pyramid” shown in (FIGURE 17-3), from which it is possible to estimate the impact of nonfatal injuries when data on fatal injuries are known.

FIGURE 17-1 Leading Causes of Injury Death, 2013

Data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “National Vital Statistics Report: Deaths: Final Data for 2013.” http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr64/nvsr64_02.pdf, accessed September 16, 2015.

Injuries that result in long-term disability, especially head and spinal cord injuries, are particularly costly to society. In 2010, for example, 1.5 million Americans sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI).7 Of these, about 50,000 died, and 280,000 were hospitalized and survived, often with lifelong disabling conditions. Many of these victims are young. Caring for these patients costs billions of dollars, much of it paid for with public funds.

Alcohol is a significant factor in a very high percentage of injuries. Sixty-five percent of traffic fatalities in 2013 involved alcohol.8 High alcohol levels are found in the blood of more than one-third of adult pedestrians killed by motor vehicles.9 Many of those fatally injured in falls, drownings, fires, and suicides are under the influence of alcohol, as are many of the perpetrators and victims of homicides. Other drugs may play a role in injury, but because blood alcohol tests are much more commonly done than tests for other drugs, the role of alcohol in injury is better documented.

The importance of alcohol’s contribution to injury accounts for its high placement on the list of “actual causes of death.” To stress the importance of driving while intoxicated as a cause of death, the authors counted alcohol-related motor vehicle deaths in both the alcohol and the motor vehicle categories, making alcohol the third leading cause and motor vehicles the sixth.10

FIGURE 17-2 Age-Adjusted Death Rates per 100,000 Population for the Three Leading Causes of Injury Death—United States, 1980–2013

Data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Wonder, wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html and wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html, accessed September 16, 2015.

FIGURE 17-3 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Burden of Injury, United States, 2009–2013”

Data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/injury.htm, accessed September 16, 2015.

Analyzing Injuries

While injuries are generally brought on by human behavior, injury researchers have increasingly sought to understand the role of the environment in causing an injury-producing event and in influencing the severity of the resulting injury. The public health approach to injury control analyzes injuries, like the approach to infectious diseases, in terms of a chain of causation: the interactions over time between a host, an agent, and the environment. To analyze an injury-causing event requires information about the person (host) who initiates the event and/or suffers the injury, the agent (automobile, firearm, swimming pool), and the environment (road conditions, weather, involvement of other people) before, during, and after the event.

To prevent certain injury-causing events from occurring in the first place—primary prevention—analysts seek to understand the conditions prevailing before each such event. For example, characteristics of the host (e.g., alcohol intoxication), the agent (e.g., defective brakes), and the environment (e.g., a dark and rainy night) are all relevant to whether a motor vehicle crash occurs. Conditions prevailing during the event affect the outcome of the crash. Thus, wearing a seat belt (host), equipping a car with an airbag (agent), and driving on a divided highway (environment) may allow the driver to avoid serious injury during a crash—secondary prevention. Tertiary prevention depends on conditions after the crash that determine whether the victim survives the injury and the extent of any resulting disability. The availability and quality of emergency care are major factors in tertiary prevention.

Because motor vehicle injuries cause so many deaths, they were the first category of injuries to be analyzed and subjected to systematic prevention efforts. Much data are available on conditions surrounding motor vehicle crashes, and methods for preventing motor vehicle injuries are highly developed. National highway safety programs were launched two decades before Congress identified injury as a general public health problem and established the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the CDC.

Injury-control efforts developed for motor vehicle injuries have served as a model for more embryonic efforts to control other categories of injury. Early prevention strategies focused on changing people’s behavior by the classic public health methods of education and regulation. As with many public health issues related to behavior, regulation is usually more effective than education in getting people to change their behavior. In the earliest days of traffic safety efforts, for example, society learned that laws regarding speed limits and traffic lights were necessary to control the chaos on the roadways.

Modern injury control began, however, with the recognition that engineering plays an important role in the causation of injuries and their severity. Sharp objects cause more damage to the human body than blunt ones; an impact distributed over a broad surface results in a less severe injury than that to a smaller surface; if deceleration can be controlled and made less sudden, the body can better withstand the force. In general, automatic protections are more effective than measures that require effort, and the more effort a measure requires, the less likely it is to be employed. Thus the “three Es” of injury prevention are education, enforcement, and engineering.

These insights, first applied in the auto industry, have also been applied to prevention of many other kinds of injury—especially childhood injuries—with considerable success. For example, when the New York City Health Department noted that a large number of children died from falls out of windows, it instituted the “Children Can’t Fly” program, requiring landlords to install window guards, and the number of fatal falls was reduced by half.11 The number of children that drown in swimming pools has been reduced by laws requiring pools to be fenced. Poisonings in children can be prevented by childproof caps on medicine containers and some household chemicals. The use of smoke detectors has reduced the number of deaths from fires. State and federal regulation of the flammability of fabrics has also saved lives, especially those of children—due to laws on children’s sleepwear. As a result of these measures and others, fatal injury rates among small children have declined markedly in recent years.1(Table 21),12

Motor Vehicle Injuries

Attention was focused on the problem of motor vehicle injuries by Ralph Nader’s indictment of the automobile industry in his book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, published in 1966. Congress responded by passing the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, which established the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and empowered it to set safety standards for new cars, such as installation of seat belts, laminated windshields, collapsible steering assemblies, and dashboard padding. Hundreds of thousands of drivers had died from being impaled on unyielding steering columns. Heads and faces of front-seat passengers had been cut by sharp dashboard edges and by glass from broken windshields. The safer designs mandated by the 1966 legislation led to an enormous reduction in both injury and mortality.11

NHTSA was also required to collect data on motor vehicle–related deaths and to conduct research aimed at prevention of motor vehicle collisions and amelioration of their effects. Among other activities, NHTSA has an ongoing program of crash-testing various vehicle models, seeking to understand how further improvements in engineering could protect occupants during a crash. These studies have led to further improvements in automobile design—including headrests that protect their occupants during rear-end collisions, strengthened side bars to protect occupants during side crashes, and airbags—now required by federal law.13

While requirements that vehicles more effectively protect their occupants during a crash are an important part of injury control (secondary prevention), preventing crashes from occurring in the first place (primary prevention) is the highest priority. Characteristics of the vehicle such as turn signals and brake lights help prevent crashes. State laws that require annual inspections of these devices, as well as of brakes and tires, are aimed at ensuring that defects in vehicles do not lead to injuries. Beginning with 2011 models, the NHTSA rates cars with a 5-star safety ratings system that includes crash avoidance technology such as electronic stability control, lane departure warnings, and forward collision warnings.14 Environmental features, especially improvements in highway design, have been shown to prevent crashes. Divided highways, raised lane dividers embedded in road surfaces, rumble strips at road edges, and “wrong-way” signs at off ramps can help to prevent mistakes by drivers.

Injury control methods that target the driver depend on both education and enforcement, and they exemplify the typical difficulties in getting people to practice healthier behaviors. Because alcohol plays such a major role in fatal crashes, laws against drinking and driving are virtually universal. Their effectiveness depends on how well they are enforced, however. The activism of volunteer groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) has helped to raise public consciousness about the extent of the problem, and tolerance for drinking and driving has declined in recent years. In addition to imposing severe penalties for being caught driving drunk, many states have expanded legislation to make establishments that serve alcohol liable for serving minors or persons already obviously intoxicated.

After alcohol, the second most important factor in fatal crashes is youth: 9 percent of drivers in fatal crashes are between 15 and 20 years old, even though those in this age group make up only 6 percent of all drivers.15 According to NHTSA, this is believed to be due in part to inexperience: Driving is a complex task, and new drivers are more likely to make mistakes. These crashes are also due to risk-taking behavior and poor judgment.

Most states have now addressed the issue by implementing graduated driver-licensing systems by which young drivers must pass through one or two preliminary stages over a period of time before they are allowed a full license.16 NHTSA has developed a model law that includes the following provisions: With a learner’s permit, a licensed adult must be in the vehicle at all times; the young person must remain crash-free and conviction-free before being allowed to take a road test for a provisional license. Nighttime driving is restricted for those with a provisional license. Young drivers must remain crash-free and conviction-free for a year before moving to a full license. As of 2008, all states have adopted some form of the graduated system, although there is significant variation among states in the restrictions imposed at different stages.17 Graduated licensing has been successful in preventing traffic fatalities among young people: States that have adopted the system have experienced significant reductions in crashes by drivers less than 20 years old.

In addition to being inexperienced, young drivers may also be just starting to drink, and doing both together can be fatal. In 2012, 28 percent of drivers 15 to 20 years old who were killed in crashes had alcohol in their blood.15 The federal government and many states have made concerted efforts to reduce drinking and driving among young people. One attempt to deal with the problem was a federal law requiring states to increase the drinking age to 21 to receive highway funds (the law became effective in 1988).11 In 1995, a similar federal law required states to pass zero tolerance laws for drivers under 21 years old. Since 1998, all states and the District of Columbia have laws setting a limit of 0.02 percent blood-alcohol concentration or below, suspending driver’s licenses for those found in violation. The evidence indicates that this is an effective approach to saving lives.18

Speed limits are an important factor in highway injuries. In 1974, Congress imposed a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour to conserve fuel at the time of the Arab oil embargo. That law, which contributed to a 16 percent decline in traffic fatalities between 1973 and 1974, was revoked in 1995 as part of the deregulation trend.11 Many states have raised their speed limits as a result, including 40 states that have limits of 70 miles per hour or above on rural interstates.19

The use of seat belts has been shown to reduce fatalities by 40 to 50 percent. Child-safety seats can reduce the risk of a child’s being killed during a collision or sudden stop by 71 percent.11 These engineering measures require people to use them correctly, however, and even state laws requiring the use of seat belts and child safety seats are widely ignored. In states that have primary seat belt laws—laws allowing police officers to pull over drivers and ticket them merely for not wearing a seat belt—the rate of seat belt use is higher than it is in states that have secondary laws—laws that permit police to issue tickets for seat belt violations only after stopping a driver for another reason. As of July 1, 2015, 34 states and the District of Columbia have primary laws, and 15 have secondary laws. New Hampshire has no seat belt law for adults. All states and the District of Columbia have child restraint laws, though the types of restraints for various age children varies among the states.20

An issue that has recently come to the attention of traffic safety advocates is cell phone use while driving. The NHTSA collects data on distracted driving, which includes using a cell phone, eating, reading, and using a navigational system, all of which degrade the driver’s performance. According to NHTSA, in 2013 3154 people were killed in motor vehicle crashes involving distracted drivers..21 As of July 1, 2015, 14 states and the District of Columbia had laws banning the use of handheld cell phones while driving, and an additional 23 states ban their use by novice drivers.22 No state has banned use altogether, although the evidence indicates that even hands-free phones can cause significant distraction to the driver. Even more risky than talking on a cell phone is text messaging, which has become increasingly common, especially among younger drivers. A study that used video cameras installed in the cabs of long-haul trucks found that when drivers texted, their risk of a collision increased 23-fold.23 Other studies suggest that the risk among drivers of passenger cars is similar. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia ban text messaging while driving, and an additional two states ban the practice for novice drivers.22

In 1968, when implementation of federal traffic safety legislation began, almost 55,000 Americans died each year from motor vehicle–related injuries. The national effort to reduce this toll has had significant success. By 1993, the number had declined to just over 40,000 fatalities per year despite the fact that many more cars were on the roads and that the number of miles driven has more than doubled.3 Since then, the downward trend halted for over a decade and then dropped dramatically to 32,367 in 2011. The fatality rate per 100 million vehicle miles of travel was at an all-time low in 2011.24 Future progress in traffic safety could depend on factors such as the price of gasoline. High gas prices tend to lead people to drive less. They also encourage people to buy smaller cars. When gas prices are low, heavier vehicles such as minivans, pickup trucks, and sport utility vehicles are popular, contributing to increases in traffic fatalities because crashes between vehicles of widely disparate size and weight cause high risk to the occupants of the smaller vehicle. Sport utility vehicles, vans, and pickup trucks, with their higher center of gravity, are more likely to roll over in crashes than sedans, however, offsetting the advantage occupants get from their size.

Pedestrians, Motorcyclists, and Bicyclists

About 14 percent of people killed in motor vehicle crashes are pedestrians, and public health efforts are also directed at preventing these injuries.25 Elderly people have the highest risk for being killed by a motor vehicle while walking. Nineteen percent of pedestrians killed by motor vehicles are 65 or older.25 Most of these injuries occur in urban areas. A 1985 study investigated reasons for a high fatality rate among older pedestrians along Queens Boulevard in a part of New York City inhabited by large numbers of senior citizens. It was found that elderly persons took an average of 50 seconds to cross the 150-foot wide boulevard, while the “walk” sign allowed only 35 seconds. Moreover, because of the boulevard’s width and because vision loss is common among the elderly, many pedestrians could not read the “walk/don’t walk” signs, which were located on the far side of the boulevard. The traffic safety unit installed additional signs on the median strips so that they could be more easily seen, and they reset the signs to allow more time for crossing. After implementation of these and other measures, such as stricter enforcement of speed limits, the rate of death and severe injuries among pedestrians fell by 60 percent.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree