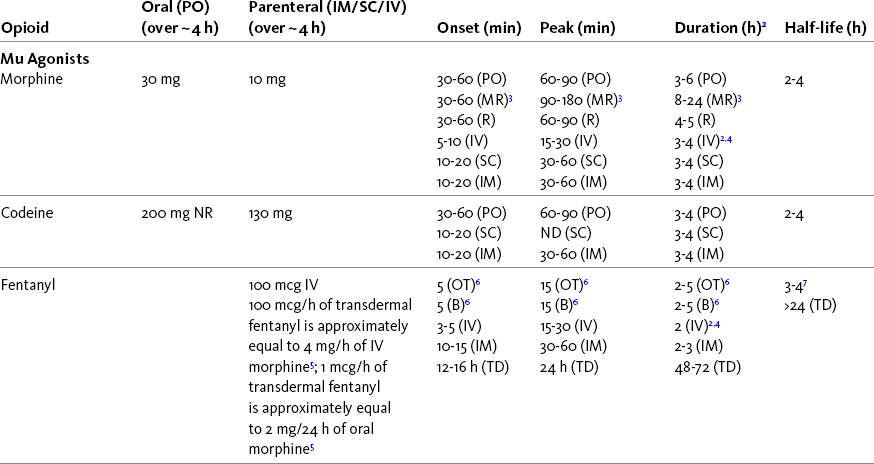

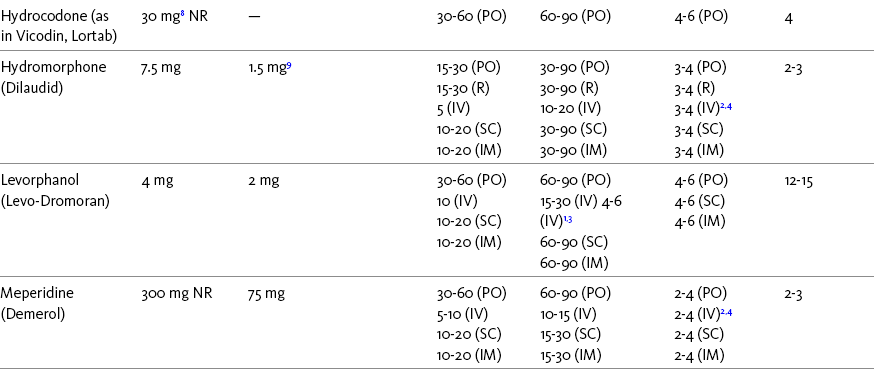

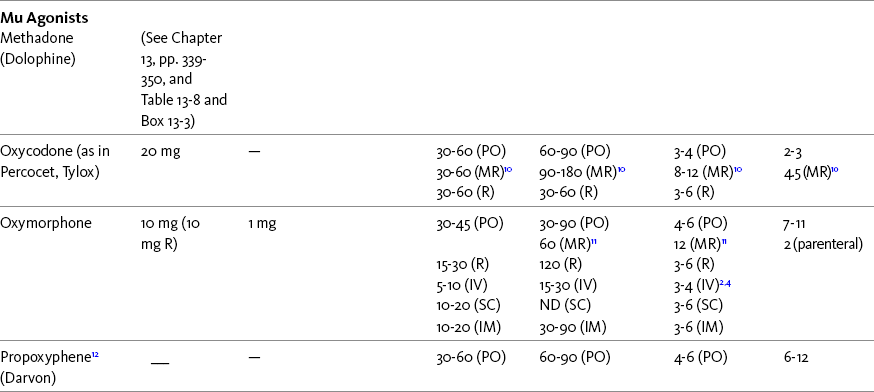

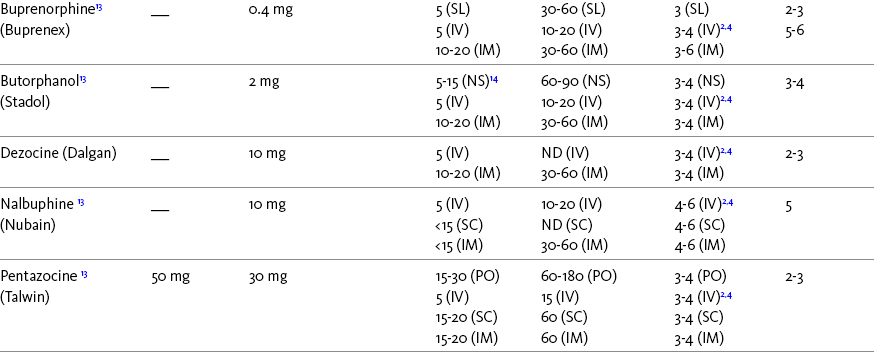

Chapter 16 Selecting an Analgesic and Route of Administration Identifying the Need for an Opioid Dose Increase Titration in Patients with Cancer Pain Titration in Patients with Persistent Noncancer Pain Titration in Patients with Severe Acute Pain Speed of Intravenous Injection As a rule, treatment of moderate-to-severe cancer pain and persistent noncancer pain is started with just one opioid analgesic at a time by one route of administration. For example, the same drug and route are usually used for the short-acting opioid for breakthrough pain and for the around-the-clock (ATC) long-acting opioid. Starting with one drug and route at a time allows for simpler interpretation of adverse effects, if they occur, and presumably lowers the risk for additive toxicity. Notwithstanding those considerations, there are circumstances that may support the initiation of opioid therapy with more than one drug or route concurrently. For example, the emerging role of the oral transmucosal, rapid-onset fentanyl formulations for breakthrough pain was discussed in Chapter 14; these are often administered with transdermal or oral opioids for persistent pain. With close monitoring, the concomitant administration of a parenteral opioid for breakthrough pain may ensure very rapid onset of relief while a baseline drug is administered orally. During planned long-term therapy, opioid selection is highly individualized, and treatment is usually initiated with a short-acting opioid, which can be titrated to effective analgesia more rapidly than a long-acting opioid (Fine, Mahajan, McPherson, 2009). As discussed in previous chapters, patients with persistent pain are commonly switched to a long-acting opioid to provide consistent pain relief and improve sleep and function. Initiating an opioid regimen in addition to an adjuvant analgesic is often warranted. For example, it may be necessary to use an opioid initially to control moderate to severe pain associated with a persistent noncancer pain syndrome for which the appropriate mainstay analgesic is an adjuvant that requires gradual titration over days or weeks before becoming effective (see Section V). In this case, it would be inhumane to expect the patient to endure severe pain while the adjuvant analgesic takes effect. As soon as the moderate to severe pain is resolved, the opioid can be tapered and discontinued if thought to be unnecessary to the treatment plan. Occasionally, two different routes of administration at the same time may be appropriate for postoperative pain. For example, continuous peripheral nerve blockade is often administered in conjunction with oral opioid analgesics or IV patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) (see Chapter 26 for continuous peripheral nerve blockade); however, the practice of using two different parenteral routes of administration at the same time or parenteral and intraspinal routes at the same time to administer opioids must be carried out with caution and appropriate monitoring. In particular, the administration of intramuscular (IM) opioids to opioid-naïve patients receiving IV or intraspinal analgesia can result in excessive sedation and clinically significant respiratory depression (see Chapter 19). The term equianalgesia means approximately equal analgesia and is used when referring to the doses of various opioid analgesics that provide approximately the same amount of pain relief. Using the equianalgesic chart in Table 16-1 as an example, note that the chart provides a list of analgesics at doses, both oral and parenteral (with other routes such as rectal as appropriate), that are approximately equal to each other and theoretically interchangeable in their ability to provide pain relief in opioid-naïve patients. These doses are also referred to as equianalgesic dose units. Most of the doses in equianalgesic charts are made on the basis of single-dose studies, commonly conducted in surgical patients and using morphine, 10 mg IM, for comparison (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, et al., 2009). The parenteral doses listed are typical of IM doses given approximately every 3 to 4 hours. Equianalgesic dose calculation provides a basis for selecting the appropriate starting dose when changing from one opioid drug or route of administration to another. However, these calculations are just estimates and vary with repeated dosing and with opioid rotation (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009; Shaheen, Walsh, Lasheen, et al., 2009). The optimal dose for the patient is always determined by titration (Fine, Portenoy, 2007). Table 16-1 Equianalgesic Dose Chart *This table provides equianalgesic doses and pharmacokinetic information about selected opioid drugs. Characteristics and comments about selected mu opioid agonist drugs can be found in Table 13-1, pp. 326-327. 1An expert panel was convened for the purpose of establishing a new guideline for opioid rotation and recently proposed a two-step approach (Fine, Portenoy, Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). The approach presented in the text for calculating the dose of a new opioid can be conceptualized as the panel’s Step One, which directs clinicians to calculate the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid based on the equianalgesic table. Step Two suggests that clinicians perform a second assessment of patients to evaluate the current pain severity (perhaps suggesting that the calculated dose be increased or decreased) and to develop strategies for assessing and titrating the dose as well as to determine the need for breakthrough doses and calculate those doses (see Box 16-2). The specific steps provided in the examples in the text reflect the panel’s two-step approach (see Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). 2Duration of analgesia is dose dependent; the higher the dose, usually the longer the duration. 3As in, e.g., MS Contin and Oramorph (8 to 12 hours) and Avinza and Kadian (12 to 24 hours). 4IV boluses may be used to produce analgesia that lasts nearly as long as IM or SC doses; however, of all routes of administration, IV produces the highest peak concentration of the drug, and the peak concentration is associated with the highest level of toxicity (e.g., sedation). To decrease the peak effect and lower the level of toxicity, IV boluses may be administered more slowly (e.g., 10 mg of morphine over a 15-min period); or smaller doses may be administered more often (e.g., 5 mg of morphine every 1 to 1.5 hours). 5This is the ratio that is used clinically. 6The delivery system for transmucosal fentanyl influences potency, e.g., buccal fentanyl is approximately twice as potent as oral transmucosal fentanyl (see Chapter 14). 7At steady state, slow release of fentanyl from storage in tissues can result in a prolonged half-life (e.g., 4 to 5 times longer). 8Equianalgesic data are not available. 9The recommendation that 1.5 mg of parenteral hydromorphone is approximately equal to 10 mg of parenteral morphine is based on single-dose studies. With repeated dosing of hydromorphone (as during PCA), it is more likely that 2 to 3 mg of parenteral hydromorphone is equal to 10 mg of parenteral morphine (see Chapter 13). 1265 to 130 mg = approximately 1/6 of all doses listed in this chart. 13Used in combination with mu agonist opioids, this drug may reverse analgesia and precipitate withdrawal in opioid-dependent patients. 14In opioid-naive patients who are taking occasional mu agonist opioids, such as hydrocodone or oxycodone, the addition of butorphanol nasal spray may provide additive analgesia. However, in opioid-tolerant patients such as those receiving ATC morphine, the addition of butorphanol nasal spray should be avoided because it may reverse analgesia and precipitate withdrawal. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 444-446, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from American Pain Society (APS). (2003). Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and chronic cancer pain. Glenview, IL, APS; Breitbart, W., Chandler, S., Eagel, B., et al. (2000). An alternative algorithm for dosing transdermal fentanyl for cancer-related pain. Oncology, 14(5), 695-705. See discussion in same issue, pp. 705, 709-710, 712, 17; Coda, B. A., Tanaka, A., Jacobson, R. C., et al. (1997). Hydromorphone analgesia after intravenous bolus administration. Pain, 71(1), 41-48; Donner, B., Zenz, M., Tryba, M., et al. (1996). Direct conversion from oral morphine to transdermal fentanyl: A multicenter study in patients with cancer pain. Pain, 64(3), 527-534; Dunbar, P. J., Chapman, C. R., Buckley, F. P., et al. (1996). Clinical analgesic equivalence for morphine and hydromorphone with prolonged PCA. Pain, 68, 226-270; Fine, P. G., Portenoy, R. K., & Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. (2009). Establishing best practices for opioid rotation: Conclusions of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage, 38(3), 418-425; Gutstein, H. B., & Akil, H. (2006). Opioid analgesics. In L. L. Brunton, J. S. Lazo, & K. L. Parker (Eds.), Goodman & Gilman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11, New York, McGraw-Hill; Hanks, G., Cherny, N. I., Fallon, M. (2004). Opioid analgesic therapy. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, N. I. Cherny, et al (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 3, New York, Oxford Press; Johnson, R. E., Fudala, P. J., & Payne, R. (2005). Buprenorphine: Considerations for pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage, 29(3), 297-326; Kaiko, R. F., Lacouture, P., Hopf, K., et al. (1996). Analgesic onset and potency of oral controlled release (CR) oxycodone CR and morphine. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 59(2), 130-133; Knotkova, H., Fine, P. G., & Portenoy, R. K. (2009). Opioid rotation: The science and limitations of the equianalgesic dose table. J Pain Symptom Manage, 38(3), 426-439; Lawlor, P., Turner, K., Hanson, J., et al. (1997). Dose ratio between morphine and hydromorphone in patients with cancer pain: A retrospective study. Pain, 72(1, 2), 79-85; Manfredi, P. L., Borsook, D., Chandler, S. W., et al. (1997). Intravenous methadone for cancer pain unrelieved by morphine and hydromorphone: Clinical observations. Pain, 70, 99-101; Portenoy, R. K. (1996). Opioid analgesics. In R. K. Portenoy, & R. M. Kanner (Eds.), Pain management: Theory and practice, Philadelphia, FA Davis; Sittl, R., Likar, R., & Nautrup, B. P. (2005). Equipotent doses of transdermal fentanyl and transdermal buprenorphine in patients with cancer and noncancer pain: Results of a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ther, 27(2), 225-237; Skaer, T. L. (2004). Practice guidelines for transdermal opioids in malignant pain. Drugs, 64(23), 2629-2638; Skaer, T. L. (2006). Transdermal opioids for cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 4, 24; Vogelsang, J., & Hayes, S. R. (1991). Butorphanol tartrate (Stadol). A review. J Post Anesthes Nurs, 6(2), 129-135; Weinberg, D. S., Inturrisi, C. E., Reidenberg, B., et al. (1988). Sublingual absorption of selected opioid analgesics. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 44, 335-342; Wilson, J. M., Cohen, R. I., Kezer, E. A., et al. (1995). Single and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of dezocine in patients with acute and chronic pain. J Clin Pharmacol, 35, 395-403. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. In contrast to the patient who is medically compromised, a healthy patient with severe pain who is to receive parenteral morphine might be prescribed as much as 10 mg of morphine parenterally every 4 hours. If, instead of severe pain, the patient has moderate pain, the starting dose would be 50% of 10 mg (5 mg) of morphine, and for mild pain, 25% of 10 mg (2.5 mg) (Box 16-1). When administered by the IV route, the total dose is given in smaller boluses over the 4-hour interval. Bolus doses over a 4-hour period are usually calculated by dividing the 4-hour dose by 4. In other words, the bolus dose is one-fourth of the 4-hour dose. In patients with cancer pain and in opioid-naive postoperative or trauma patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who require parenteral opioids, a maintenance continuous infusion is initiated after pain is controlled by IV or SC boluses (Coyle, Cherny, Portenoy, 1995). As mentioned, additional boluses offered every 15 to 30 minutes may be prescribed for the management of breakthrough pain (see Breakthrough Doses, discussed next, and Chapter 17 for continuous infusions in opioid-naïve patients outside of the ICU). The term breakthrough dose is used interchangeably with the terms supplemental dose or rescue dose. It is now conventional practice to offer all patients with pain related to active cancer or other serious illnesses who are receiving ATC opioid analgesics access to doses of a fast-acting mu agonist opioid analgesic to treat breakthrough pain (see Chapter 12 for a detailed discussion of breakthrough pain). The use of these short-acting supplemental doses for breakthrough pain should not be considered conventional practice in the large and heterogeneous population with persistent noncancer pain. In this population, the decision to provide such a treatment should be made after a careful risk-to-benefit analysis that assesses both the risk of pharmacologic adverse effects such as peak concentration sedation and the risk of problematic drug-related behaviors that may be consistent with abuse or addiction. Well-controlled research is needed to inform decisions on breakthrough pain in this diverse population (Devulder, Jacobs, Richarz, et al., 2009; Fine, Portenoy, 2007). For patients taking oral opioids, the recommended amount of opioid for breakthrough doses is within a range of approximately 5% to 15% of the total daily dose of the ATC opioid analgesic; however, some clinicians prefer to use 10% to 15% unless there are circumstances that suggest a conservative calculation (5%) should be made, for example, in the case of a frail patient or a patient older than 70 years (Box 16-2). This calculation is used consistently, regardless of the total daily dose of opioid. For example, the range of a given breakthrough dose for a patient receiving a total daily dose of 8000 mg of modified-release morphine would be 800 mg (10%) to 1200 mg (15%).

Initiating Opioid Therapy

Selecting an Analgesic and Route of Administration

Selecting an Opioid Dose

Using the Equianalgesic Chart

A Guide to Using Equianalgesic Dose Charts*

Continuous Infusions

Breakthrough Doses