13 Inflammatory bowel disease

Epidemiology

The incidence of new cases of ulcerative colitis in Europe and USA is 2–8 per 100,000 per year with a prevalence of 40–80 per 100,000 per year. The incidence has remained fairly static over the last 40 years. In the UK, Crohn’s disease occurs with a similar frequency to ulcerative colitis with around 4 per 100,000 per year and a prevalence of 50 per 100,000. The rates in central and southern Europe are lower. In South America, Asia and Africa, Crohn’s disease is uncommon but appears to be on the rise (Mpofu and Ireland, 2006).

Aetiology

Environmental

Diet

Evidence that dietary intake is involved in the aetiology of IBD is inconclusive, although several dietary factors have been associated with IBD, including fat intake, fast food ingestion, milk and fibre consumption, and total protein and energy intake. A large number of case-control studies have reported a causal link between the intake of refined carbohydrates and Crohn’s disease (Gibson and Shepherd, 2005). The mechanism for diet as a trigger is very poorly understood.

Those that are breastfed as infants have a reduced risk of developing IBD (Mpofu and Ireland, 2006).

Smoking

There is a higher rate of smoking amongst patients with Crohn’s disease than in the general population, with up to 40% of patients with the disease being smokers. Smoking worsens the clinical course of the disease and increases the risk of relapse and the need for surgery. Fewer patients with ulcerative colitis smoke (approximately 10%). Former smokers are at the highest risk of developing ulcerative colitis, while current smokers have the least risk. Stopping smoking can provoke the emergence of ulcerative colitis. This indicates that smoking may help to prevent the onset of the disease. The explanation for this is unclear. However, it is thought that in addition to its effect on the inflammatory response, the chemicals absorbed from cigarette smoke affect the smooth muscle inside the colon, potentially altering gut motility and transit time. In some studies, nicotine has been shown to be an effective treatment for ulcerative colitis (Guslandi, 1999).

Drugs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac have been reported to exacerbate IBD (Felder et al., 2000). It is thought this may result from direct inhibition of the synthesis of cytoprotective prostaglandins. Antibiotics may also precipitate a relapse in disease due to a change in the enteric microflora. The risk of developing Crohn’s disease is thought to be increased in women taking the oral contraceptive pill, possibly caused by vascular changes.

Appendicectomy

Appendicectomy has a protective effect in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (Radford-Smith et al., 2002). It is unclear whether this protective effect is immunologically based or whether individuals who develop appendicitis and consequently have an appendicectomy are physiologically, genetically or immunologically distinct from the population that is predisposed to IBD.

Genetic

Fifteen percent of first degree relatives have IBD. There is mounting evidence that Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis result from an inappropriate response of the immune system in the mucosa of the gastro-intestinal tract to normal enteric flora (Ahmad et al., 2004). Since the mid-1990s there has been considerable progress in understanding the contribution of genetics to IBD susceptibility and phenotype.

Ethnic and familial

Jews are more prone to IBD than non-Jews, with Ashkenazi Jews having a higher risk than Sephardic Jews. In North America, IBD is more common in whites than blacks. First-degree relatives of those with IBD have a 10-fold increase in risk of developing the disease. A familial link is supported from research showing a 15-fold greater concordance for IBD in monozygotic (identical) than dizygotic (non-identical) twins (Jess et al., 2005).

Pathophysiology

Disease location

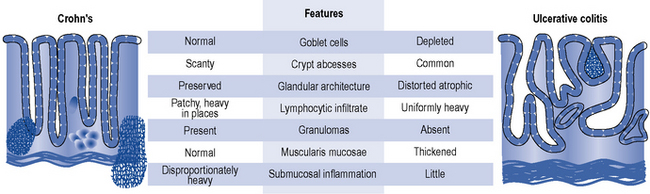

The character and distribution, both macroscopic and microscopic, of chronic inflammation define and distinguish ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Table 13.1 shows the differences in location and distribution of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Figure 13.1 details the histological differences.

Table 13.1 Location and distribution of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

| Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Colon and rectum 40% proctitis 20% pancolitis 10–15% backwash ileitis | Entire gut (mouth to anus, rectal sparing) 45% ileocaecal disease 25% colitis only 20% terminal ileal disease 5% small bowel disease 5% anorectal, gastroduodenal, oral disease |

| Distribution | Continuous, diffuse | Often discontinuous and segmental ‘skip lesions’ |

| Full thickness (transmural) | ||

| No granulomas | Granulomatous inflammation | |

| Inflammation of mucosa | ||

| Ulceration if fine and superficial | Deep ulceration with mucosal extension | |

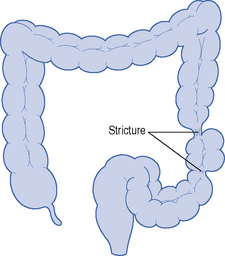

| Fissures, fistulae and stricture | Absent | Common |

| Perianal disease | Absent | Present |

Clinical manifestation

The clinical differences between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are described in Table 13.2.

Table 13.2 Clinical differences between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

| Symptom | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease |

|---|---|---|

| Prominent symptom | Bloody diarrhoea | Diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss 30%, no gross bleeding |

| Fever | ++ | ++ |

| Abdominal pain | Variable | ++ |

| Diarrhoea | +++ | +++ |

| Rectal bleeding | +++ | ++ |

| Weight loss | + | ++ |

| Sign of malnutrition | + | ++ |

| Abdominal mass | − | ++ |

| Dehydration | +++ | ++ |

| Iron-deficiency anaemia, raised CPR/ESR, hypoalbuminaemia | ++ | ++ |

CPR, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; +, the likelihood this symptom will be present; −, symptom absent in patient.

Crohn’s disease

Extra-intestinal complications of IBD

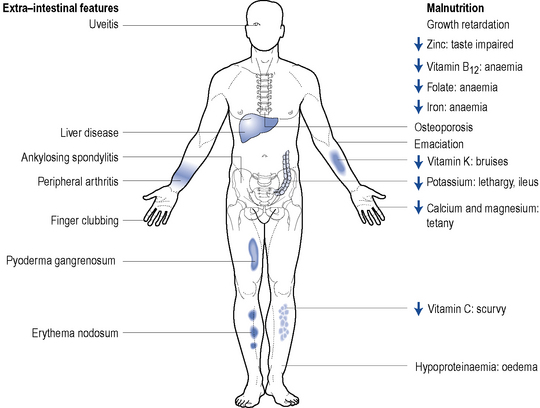

Around 20–30% of patients with IBD will present with extra-intestinal manifestations. They are more commonly seen in patients where IBD affects the colon. Complications affect the joints, skin, bone, eyes, liver and biliary tree and are more common in active disease. Figure 13.3 highlights some of the extra-intestinal features of IBD.

Thromboembolic

Thromboembolic complications occur in around 1–2% of IBD patients. The most common cause of death in hospitalised IBD patients is pulmonary embolism (Solem et al., 2004).

Investigations

Clinical assessment tools

The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) or the Harvey–Bradshaw Index (HBI) is used in most clinical trials to define remission in Crohn’s disease. However, in clinical practice the CDAI is rarely used as it needs to be measured prospectively and is complex. The HBI is a simple measure of stool frequency, pain and other clinical features that is increasingly used to document selection for and response to biologic therapy. A CDAI of <150 or an HBI ≤3 suggests patient is in remission (NICE, 2010).

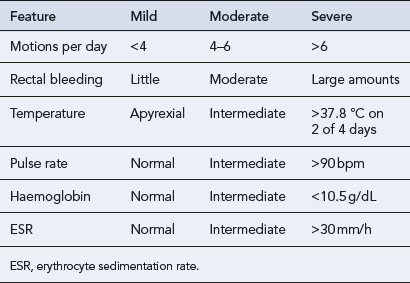

The Truelove and Witts criteria is a useful tool in defining the severity of ulcerative colitis (see Table 13.3). A severe attack is defined as more than six bloody stools a day plus one or more of the following: pulse > 90 beats/min, temperature >37.8 °C, haemoglobin <10.5 g/dL or ESR >30 mm/h. In this case, the patient should be admitted to hospital.

Table 13.3 Truelove and Witts criteria for assessing severity of ulcerative colitis (Travis et al., 2008)

Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease

Nutritional therapy

Nutritional therapy can be considered as an adjunctive or primary treatment. Although a potential problem for all patients with IBD, patients with Crohn’s disease are at particular risk of becoming malnourished and developing a variety of nutritional deficiencies (Fig. 13.3). It is, therefore, important for patients to receive optimal nutrition and dietary manipulation as needed. Low-fibre diets help to reduce clinical symptoms of intestinal obstruction in Crohn’s disease (Fernandes-Banares et al., 1999). Functional and structural damage to the small bowel can cause malabsorption problems and occasionally patients may require a low-lactose diet. Patients with poor oral intake and loss of appetite often respond to supplemental enteral feeds. Enteral nutrition in the form of an elemental or polymeric diet can be used as primary therapy and is widely employed in paediatrics (Heuschkel and Walker-Smith, 1999).

Drug treatment

Disease confined to the anus, rectum or left side of the colon is more appropriately treated with rectally administered topical preparations where the drug is applied directly to the site of inflammation (Table 13.4).

Table 13.4 Comparison of commercially available preparations for rectal administration in inflammatory bowel disease

| Generic name (proprietary name) | Formulation | Site of release |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfasalazine (Salazopyrin®) | Suppositories Retention enema | Rectum Transverse, descending colon and rectum |

| Mesalazine (Pentasa®, Salofalk®) | Retention enema | Transverse, descending colon and rectum |

| Mesalazine (Asacol®, Salofalk®) | Foam enema | Rectum and rectosigmoid colon |

| Mesalazine (Asacol©®, Pentasa®, Salofalk®) | Suppositories | Rectum |

| Prednisolone sodium phosphate (Predsol®) | Retention enema Suppositories | Transverse, descending colon and rectum Rectum |

| Prednisolone sodium metasulphobenzoate (Predenema®) | Retention enema | Transverse and descending colon |

| Prednisolone sodium metasulphobenzoate (Predfoam®) | Foam enema | Rectum and rectosigmoid colon |

| Prednisolone sodium phosphate (Predsol®) | Retention enema | Transverse and descending colon |

| Hydrocortisone acetate (Colifoam®) | Foam enema | Rectum and rectosigmoid colon |

| Budesonide (Entocort©®) | Retention enema | Rectum and rectosigmoid colon |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree