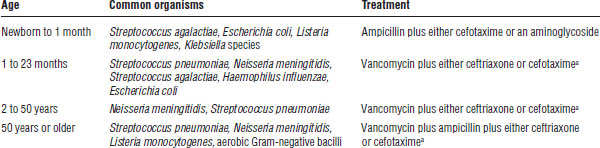

Table 33-1. Empiric Therapy for Meningitis Based on Age

Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. 2004.

a. Consider addition of rifampin if dexamethasone is given.

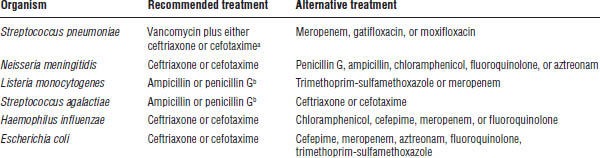

Table 33-2. Targeted Therapy for Adults with Meningitis Based on Gram-Stain

Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al., 2004.

a. Consider addition of rifampin if dexamethasone is given.

b. Consider addition of an aminoglycoside to either therapy.

Causative agents

Endocarditis can result from a variety of infectious agents including fungi and bacteria. The most common bacterial organisms are Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Enterococcus species.

Clinical presentation

Patients may present with a low-grade fever, fatigue, weakness, new heart murmur, or petechiae.

Diagnostic criteria

Endocarditis is diagnosed on the basis of patient signs and symptoms in combination with tests such as blood cultures or an echocardiogram to visualize vegetations.

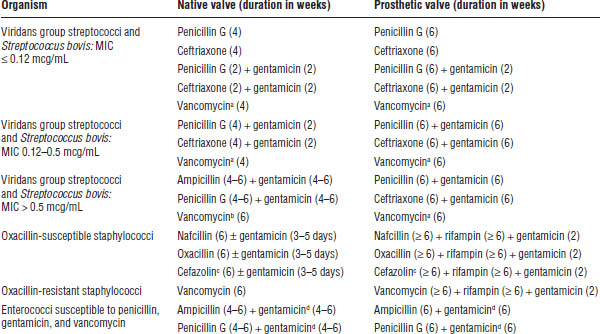

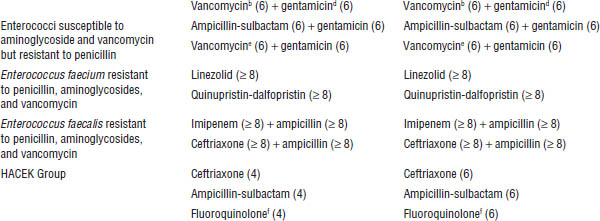

Treatment

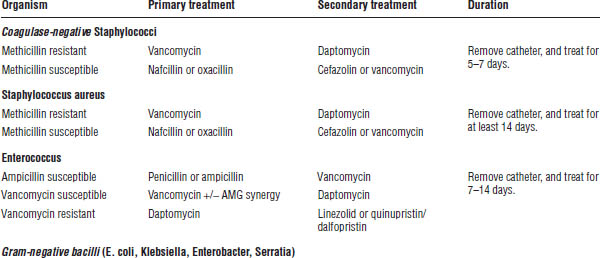

Treatment varies depending on the causative organism, susceptibility to antibiotics, and presence or absence of prosthetic devices. Table 33-3 describes therapies for endocarditis. Published guidelines provide more specific recommendations.

Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections

More than 150 million vascular devices are placed in patients in the United States each year, and infections of these devices are associated with considerable morbidity, mortality, and cost. The Infectious Diseases Society of America has recently updated recommendations for the prevention and treatment of infections of intravascular catheters.

Causative agents

Like most other infections, the predominant pathogen associated with intravascular catheters varies according to the type of device, duration the device is in place, local microbiological trends, and patient-specific risk factors. In general, coagulase-negative staphylococci and S. aureus are the most common causes of intravascular device infections. Other commonly implicated pathogens include Candida species, Enterococcus species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and enteric Gram-negative bacilli.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of intravascular catheter infections is nonspecific, consisting of fever or hypothermia, chills, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and increased or decreased WBC count. For long-term catheters, such as dialysis or tunneled catheters used for long-term intravenous (IV) therapy (chemotherapy or total parenteral nutrition), symptoms may occur when the catheter is accessed.

Diagnostic criteria

When a catheter-related infection is suspected, blood cultures should be drawn from the catheter and from a peripheral site prior to initiating antibiotics. If possible, the catheter should be removed and cultured by rolling it on a plate of agar. A definitive diagnosis is made based on the following: (1) the same organism grows from at least one bottle cultured from the catheter and one bottle cultured from the peripheral site or (2) when the same organisms grow from the blood cultured from the catheter and more than 15 colony-forming units grow from the catheter-tip culture.

Table 33-3. Treatment of Endocarditis

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al., 2005.

HACEK = Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella.

a. Use vancomycin only if unable to use penicillin or ceftriaxone.

b. Use vancomycin only if unable to use ampicillin or penicillin.

c. Cefazolin should be used for nonanaphylactoid penicillin-allergic patients. If the patient has an anaphylactoid allergy, use vancomycin.

d. Substitute streptomycin if patient is resistant to gentamicin.

e. Use vancomycin only if unable to use ampicillin-sulbactam or if strain has intrinsic penicillin resistance.

f. Use a fluoroquinolone only if unable to use ceftriaxone or ampicillin-sulbactam.

Treatment

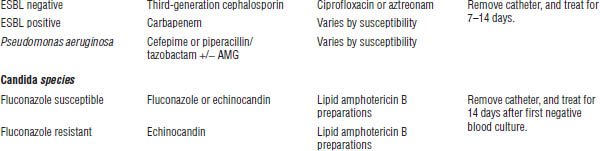

The agent selected and duration of treatment of intravascular device infections depend on the location and type of device, organism isolated, whether the device is removed, clinical response, and additional patient comorbidities. When possible, the infected device should be removed. If no specific risk factors are present, initial empiric treatment should include vancomycin to cover methicillin-resistant staphylococci (Table 33-4). If the MIC of the majority of S. aureus at your institution is greater than 2mg/dL, then Cubicin (daptomycin) should be used empirically. Linezolid should not be used, though, for treatment of catheter-related infections. Selection of coverage for Gram-negative organisms should be based on local susceptibility data and severity of disease. Double-coverage of Gram-negative bacteria is not recommended unless the patient has risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria or is extremely ill (septic shock, neutropenia). Empiric coverage of Candida should be given to patients with a history of femoral catheter placement, use of total parenteral nutrition, prolonged use of antibiotics, hematologic malignancy, transplant, or colonization by Candida species at multiple sites.

Table 33-4. Treatment of Uncomplicated Catheter-Related Infections in Patients without Malignancy or Immunosuppression

AMG = amikacin, tobramycin, or gentamicin; AMG synergy = gentamicin or streptomycin; ESBL = extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; carbapenem = doripenem, ertapenem, imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem.

Febrile Neutropenia

Patients with cancer often have marked decreases in WBCs caused by their chemotherapy regimen. Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 500 cells/mL [ANC = (% Bands + % Segs) × WBC]. When the ANC is less than 500 cells/mL, fever may be the only symptom of infection that the patient may display; therefore, fever in a neutropenic patient should prompt an investigation for an infection and the initiation of antibiotics.

Causative agents

Because any infection can cause fever in neutropenic patients, a wide variety of bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens may be implicated. Site of infection, local microbiological trends, prior cultures, and current cultures all help determine the causative pathogen. The most common bacterial pathogens in neutropenic patients are coagulase-negative Staphylococci, S. aureus, Enterococci, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Acinetobacter, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, and Klebsiella species.

Clinical presentation

Patients with febrile neutropenia can present with a range of symptoms, from fever to severe pneumonia to septic shock.

Diagnostic criteria

An ANC < 500 cells/mL with either a single oral temperature of ≥ 38.3°C or a temperature of ≥ 38°C for over 1 hour is diagnostic of febrile neutropenia. An extensive clinical evaluation to determine the cause of infection is recommended.

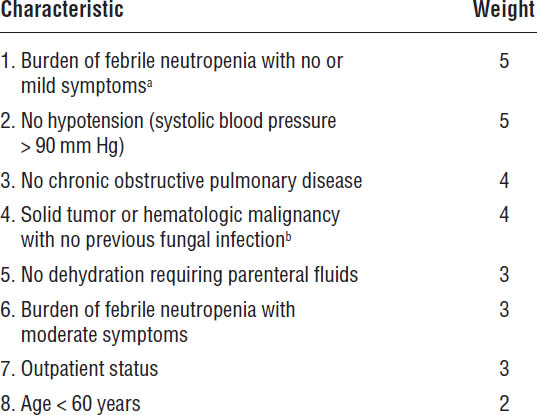

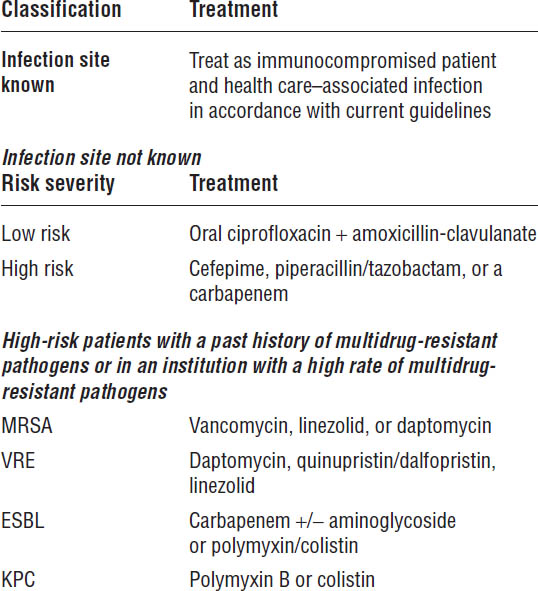

Treatment

Treatment is based on a severity risk assessment such as the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Risk-Index score (Table 33-5). Empiric coverage should be based on suspected site of infection and risk factors for multidrug-resistant pathogens. When the site of infection is known (i.e., pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infection, catheter-related bloodstream infection), treatment should be in accordance with current guidelines. If the site of infection is not identifiable, coverage of Gram-positive bacteria, enteric Gram-negative bacilli, and P. aeruginosa should be provided with a single agent or combination of agents. Routine coverage for MRSA, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE), extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) Gram-negatives, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), and Candida is not recommended. In addition, double coverage of Gram-negative bacteria is not recommended. However, in select patients at risk for the previously mentioned multidrug-resistant pathogens, expanded initial coverage should be provided.

Table 33-5. Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer Risk-Index Score

The maximum value of the score is 26.

Adapted from Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Rubenstein EB, et al., 2000.

a. Burden of febrile neutropenia refers to the general clinical status of the patient during the febrile neutropenic episode. No symptoms to mild symptoms (5); moderate symptoms (3); and severe symptoms or moribund (0). Scores of 3 and 5 are not cumulative.

b. Previous fungal infection means demonstrated fungal infection or empirically treated suspected fungal infection.

High-risk patients (MASCC score < 21) should be admitted and treated with intravenous antibiotics. Low-risk patients (MASCC score ≥ 21) may be candidates for oral antibiotic therapy or outpatient treatment. The site of infection and organism identified determines the antibiotic treatment duration. If no infectious source is identified, antibiotic treatment should be continued until the ANC is > 500 cells/mL. See Table 33-6 for treatment options.

Acute or Chronic Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is a respiratory tract infection that typically presents with a cough as the predominant symptom with a clear chest radiograph. Chronic bronchitis is a disease of the bronchi that is manifested by cough and sputum expectoration occurring for at least 3 months per year for more than 2 consecutive years. Chronic bronchitis is most commonly caused by smoking or prolonged exposure to inhalation of noxious substances. When a person with chronic bronchitis experiences a worsening of symptoms, it is referred to as an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Table 33-6. Initial Treatment of Febrile Neutropenia

Carbapenem = doripenem, imipenem/cilastatin, meropenem; aminoglycoside = amikacin, tobramycin, or gentamicin.

Causative agents

The majority of acute bronchitis infections appear to be caused by respiratory viruses such as adenovirus, coronavirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. Bacterial pathogens most commonly implicated in acute bronchitis include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, and Bordetella parapertussis. Viruses are also the most common cause of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Viral infections predispose patients to develop secondary bacterial infections. These secondary bacterial infections are often caused by S. pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, or Haemophilus influenzae.

Clinical presentation

Acute bronchitis usually presents with either productive or nonproductive cough as the predominant symptom, but fever, muscle aches, and fatigue can also be present.

Diagnostic criteria

There are no recommended diagnostic tests for acute bronchitis. Diagnosis is made by presentation with cough for less than 3 weeks with no radiological evidence of pneumonia. In addition, the common cold, asthma, and an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should be ruled out.

Treatment

Acute bronchitis should not routinely be treated with antibiotics unless B. pertussis is suspected or known to be the causative agent (Table 33-7). However, patients with acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis should be treated with antibiotics because treatment of exacerbations with antibiotics has been shown to decrease the duration of illness.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lung tissue caused by bacterial, viral, or fungal infections.

Causative agents

Multiple bacterial etiologies are possible, depending on age and predisposing conditions (Table 33-8 and Table 33-9).

Table 33-7. Treatment of Acute and Chronic Bronchitis

Illness | Treatmenta |

Acute bronchitis | Antibiotics are not to be offered or given. |

Acute bronchitis caused by Bordetella pertussis | Erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin |

Exacerbation of chronic bronchitis | Amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, minocycline |

a. Usual duration is 7–10 days.

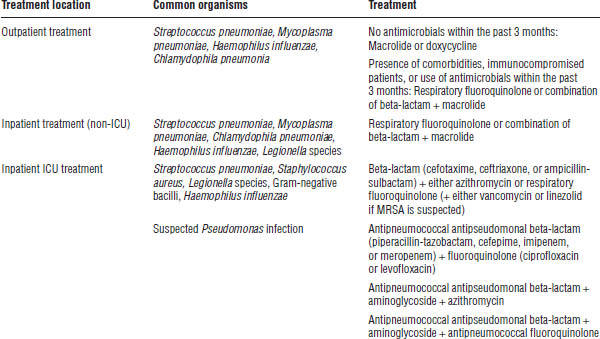

Table 33-8. Empiric Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al., 2007.

ICU = intensive care unit.

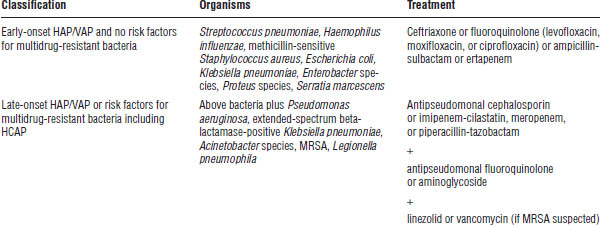

Table 33-9. Empiric Treatment of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia, Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia, and Health Care–Associated Pneumonia

American Thoracic Society Documents, 2005.

Clinical presentation

The onset of illness can be abrupt or subacute, with fever, chills, dyspnea, and productive cough predominating.

Diagnostic criteria

A diagnosis of pneumonia is based on patient signs and symptoms in combination with tests such as a chest x-ray or culture data. Blood and sputum cultures may be used to identify the causative pathogen; however, sputum cultures are often contaminated, making reliability questionable. Samples obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) have a lower rate of contamination, but a BAL is not appropriate in all patients because it is an invasive procedure.

Treatment

Treatment decisions are based upon the pneumonia classification: community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), or health care–associated pneumonia (HCAP). In CAP, empiric antibiotic selection is determined by treatment location: outpatient, inpatient, or intensive care unit (Table 33-8). Recent guideline updates also advocate empiric coverage for MRSA in patients with CAP who meet one of the following criteria: intensive care unit admission, presence of necrotizing or cavitary infiltrates, or presence of empyema. In addition, factors such as alcohol abuse, travel, animal exposure, or HIV infection increase the incidence of particular pathogens, further guiding the selection of empiric antibiotics.

HAP occurs when pneumonia develops 48 hours or more after a patient is admitted to the hospital. A patient is diagnosed with VAP when pneumonia develops 48–72 hours after a patient is placed on a ventilator. Finally, HCAP refers to pneumonia that occurs in a patient exposed to a health care environment (hospitalization ≥ 2 days in the past 90 days; residence in a nursing home or other long-term care institution; IV antibiotic treatment, chemotherapy, or wound care within the past 30 days; or treatment at a hospital or hemodialysis clinic).

Treatment for HAP or VAP is based on the onset of the infection and risk factors for multidrug-resistant organisms. Patients with HAP or VAP who have been hospitalized for more than 4 days are considered to have late-onset infection and are at risk for multidrug-resistant organisms. Other risk factors for multidrug-resistant organisms include treatment with antimicrobial agents within the past 90 days, immunosuppression, or a high rate of antibiotic resistance in the community or hospital unit. Patients with HCAP are inherently at risk for multidrug-resistant organisms, and empiric antibiotics should provide appropriate coverage. Table 33-9 outlines treatment for HAP, VAP, and HCAP.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a communicable infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It can produce a silent, latent infection as well as an active infection. Although infection of any tissue or organ with M. tuberculosis is possible, the usual site of infection is pulmonary.

Clinical presentation

Tuberculosis can present with generalized symptoms of weight loss, fever, and night sweats, along with persistent cough with productive sputum. In the absence of other symptoms, latent disease is defined by a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) test or a positive interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnosis often is made by a combination of chest x-ray findings and a positive PPD skin test or IGRA. Patients with severe HIV disease may not react to the standard PPD skin test. Individuals who have been immunized with the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine may have a false positive reaction to the PPD skin test; therefore, testing with an alternative method such as an IGRA should be considered. Sputum specimens or lung tissue may be acid-fast stained to confirm the presence of Mycobacterium species. Mycobacterial culture can confirm speciation; however, because of the extended time needed to grow the organism, sensitivities to anti-infective agents may take weeks to months to determine.

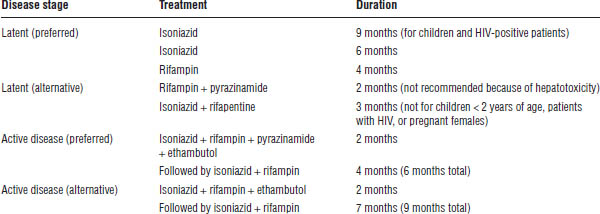

Treatment

Tuberculosis is a very slow growing bacterium that requires prolonged treatment with multiple anti-infective agents to achieve a cure and to prevent development of resistance. To ensure compliance with therapy, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends direct observed therapy for most treatment regimens for active and latent tuberculosis.

Table 33-10. Treatment of Tuberculosis

See Table 33-10 for a summary of treatments.

Intra-abdominal Infections

Intra-abdominal infections include infections of the retroperitoneal space or the peritoneal cavity.

Causative agents

A variety of bacteria are associated with intra-abdominal infections including facultative and aerobic Gram-negative bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, and Gram-positive aerobic bacteria. Major sources of infection include Escherichia coli and Bacteroides species.

Clinical presentation

Patients may present with abdominal pain and fever. Systemic manifestation can occur in severe cases.

Diagnostic criteria

Generally, patient history and physical examination are sufficient to diagnose an intra-abdominal infection. Imaging studies or exploratory laparotomy may be necessary in select patients.

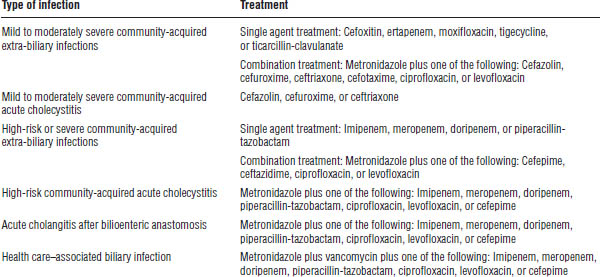

Treatment

In addition to antibiotics, fluid resuscitation may be required in cases of severe infections. Surgical procedures are essential to treatment in some patients, such as those with severe peritonitis or an abscess. Although cultures are not required in low-risk patients with a community-acquired infection, cultures of specimens obtained from the site of infection as well as susceptibility testing may prove beneficial to guiding therapy in hospital-acquired infections or higher-risk patients. Table 33-11 outlines the empiric treatment of adults with complicated intra-abdominal infections.

Infectious Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined as an increase in frequency or liquidity of stool (or both), compared to a patient’s normal stool.

Causative agents

Many disease states, drugs, and infectious organisms are associated with diarrhea.

Clinical presentation

In addition to diarrhea, the patient may present with several of the following symptoms: fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal cramping.

Diagnostic criteria

Etiology is usually determined by patient history and physical examination. Patient history should include factors such as immune status, recent travel, food exposure, or antibiotic use. Cultures and tests for toxins or parasites may be performed. Diagnosis of certain infectious organisms, such as those associated with foodborne illness, should be reported to appropriate agencies.

Table 33-11. Empiric Treatment of Adults with Complicated Intra-abdominal Infections

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al., 2010.

Treatment

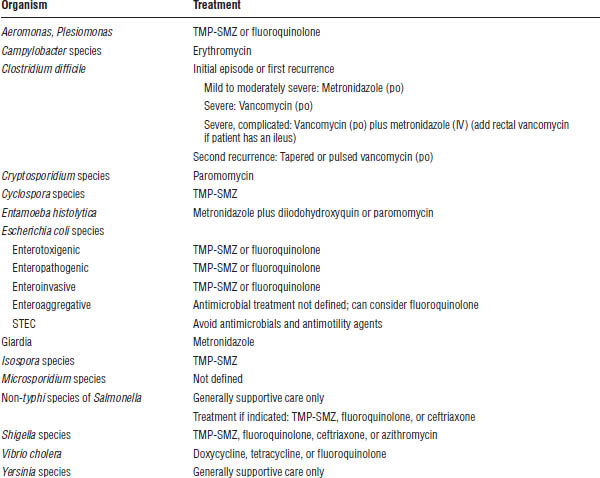

Supportive care (hydration, electrolyte replacement, antipyretics, or antiemetics) is often the only treatment provided. Antimotility agents are usually discouraged because of the potential to cause toxic megacolon, especially in cases of bloody diarrhea, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infections, or Clostridium difficile infections. Antibacterial therapy is reserved for severe presentations, patients with risk factors, or patients diagnosed with specific infectious causes. When indicated, patients with traveler’s diarrhea can be empirically treated with fluoroquinolones in adults or Septra (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) in children. Table 33-12 provides an overview of treatments for immunocompetent patients.

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

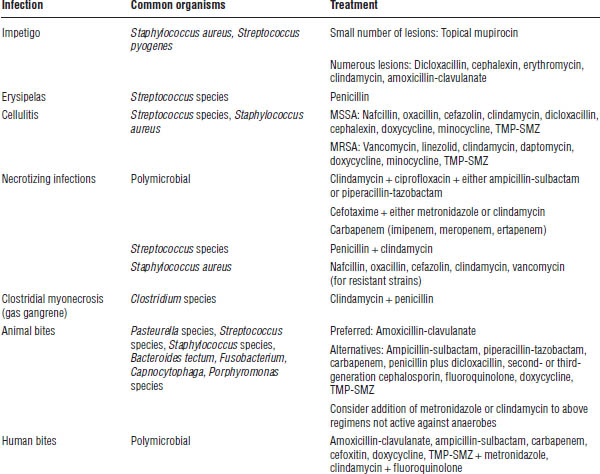

Bacterial infections of the skin and soft tissue can result in a variety of conditions. This chapter covers the following: impetigo, erysipelas, cellulitis, necrotizing infections, and infections caused by human or animal bites.

Causative agents

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are caused by a variety of organisms (Table 33-13).

Clinical presentation

SSTIs are usually characterized by erythema and edema of the skin. More serious infections can result in systemic symptoms, such as fever, tachycardia, or hypotension. Table 33-14 describes signs and symptoms of selected SSTIs.

Diagnostic criteria

For mild infections, diagnosis is usually made by physical examination. Blood or biopsy cultures and surgical intervention may be necessary in patients with severe infections.

Treatment

Treatment is based on the type and severity of infection. Usually treatment is empiric, targeting the organisms most commonly associated with the specific type of SSTI (Table 33-13). Because of the expanding incidence of MRSA, the need for additional empiric coverage of MRSA in select SSTIs is increasing (Table 33-15). MRSA should also be considered in patients unresponsive to initial therapies lacking MRSA coverage. In patients with a necrotizing infection or in immunocompromised patients, surgical intervention may be required in combination with antibiotic therapy.

Table 33-12. Treatment of Infectious Diarrhea for Immunocompetent Patients

Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al., 2010; Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al., 2001.

TMP-SMZ = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) represent a wide variety of clinical syndromes, including urethritis, cystitis, prostatitis, and pyelonephritis.

Causative agents

The most common agents are enteric Gram-negative bacilli and Enterococcus. Hospitalized, catheterized patients also may acquire Pseudomonas, Morganella, Citrobacter, and Staphylococcus species.

Clinical presentation

Lower urinary tract infections tend to present with dysuria, urinary urgency, polyuria, nocturia, and suprapubic heaviness or pain. Fever is rare in patients with lower urinary tract infections. Upper urinary tract infections, such as pyelonephritis, tend to present with flank pain and fever.

Table 33-13. Treatment of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al., 2004; Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al., 2005.

MSSA = methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; TMP-SMZ = trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnosis of UTIs is based on the presence of urinary or systemic symptoms, the presence of microorganisms in significant numbers, and the presence of WBCs in the urine sample. In general, higher numbers of organisms (> 105 cells/mL) are needed to diagnose UTIs in females compared to males (> 103 cells/mL) because more organisms can ascend the shorter female urethra.

Treatment

A variety of antibacterials may be useful for the treatment of UTIs (Table 33-16), including fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ), and Vibramycin (doxycycline). Fluoroquinolones are especially useful for the treatment of prostatitis. Length of therapy varies according to the severity of disease.

Bacterial Venereal Diseases (Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis)

Venereal diseases are diseases that can be transmitted via sexual intercourse. This section covers chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis. Patients testing positive for any sexually transmitted disease should be screened for the presence of other venereal diseases. In addition, all sexual partners should be screened and treated if indicated.

Table 33-14. Clinical Presentation of Selected Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Infection | Signs and symptoms |

Impetigo | Single or multiple localized, purulent lesions usually occurring on the head or extremities |

Erysipelas | Raised lesions with erythema and edema; involvement limited to the upper dermis |

Cellulitis | Progressive erythema and edema without raised demarcations; involvement extends into the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat |

Necrotizing infections | Rapidly progressive infection with systemic manifestations; skin necrosis and bullae may be present; involvement may extend into the fascia or muscle |

Clostridial myonecrosis (gas gangrene) | Bronze or reddish purple skin with systemic manifestations; crepitant tissue resulting from gas |

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al., 2005.

Table 33-15. Empiric Treatment of MRSA Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Infection | Signs and symptoms |

Purulent cellulitis | Clindamycin, TMP-SMZ, doxycycline, minocycline, linezolid |

Nonpurulent cellulitisa |