INTRODUCTION

Medically important infections caused by anaerobic bacteria are common. The infections are often polymicrobial—that is, the anaerobic bacteria are found in mixed infections with other anaerobes, facultative anaerobes, and aerobes (see the glossary of definitions). Anaerobic bacteria are found throughout the human body—on the skin, on mucosal surfaces, and in high concentrations in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract—as part of the normal microbiota (see Chapter 10). Infection results when anaerobes and other bacteria of the normal microbiota contaminate normally sterile body sites.

Several important diseases are caused by anaerobic Clostridium species from the environment or from normal flora: botulism, tetanus, gas gangrene, food poisoning, and pseudomembranous colitis. These diseases are discussed in Chapters 9 and 11.

GLOSSARY

Aerobic bacteria: Bacteria that require oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor and will not grow under anaerobic conditions (ie, in the absence of O2). Some Bacillus species and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are obligate aerobes (ie, they must have oxygen to survive).

Anaerobic bacteria: Bacteria that do not use oxygen for growth and metabolism but obtain their energy from fermentation reactions. A functional definition of anaerobes is that they require reduced oxygen tension for growth and fail to grow on the surface of solid medium in 10% CO2 in ambient air. Bacteroides and Clostridium species are examples of anaerobes.

Facultative anaerobes: Bacteria that can grow either oxidatively, using oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor, or anaerobically, using fermentation reactions to obtain energy. Such bacteria are common pathogens. Streptococcus species and the Enterobacteriaceae (eg, Escherichia coli) are among the many facultative anaerobes that cause disease. Often, bacteria that are facultative anaerobes are called “aerobes.”

PHYSIOLOGY AND GROWTH CONDITIONS FOR ANAEROBES

Anaerobic bacteria do not grow in the presence of oxygen and are killed by oxygen or toxic oxygen radicals (see later discussion); pH and oxidation-reduction potential (Eh) are also important in establishing conditions that favor growth of anaerobes. Anaerobes grow at a low or negative Eh.

Aerobes and facultative anaerobes often have the metabolic systems listed below, but anaerobic bacteria frequently do not.

Cytochrome systems for the metabolism of O2

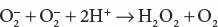

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), which catalyzes the following reaction:

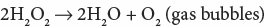

Catalase, which catalyzes the following reaction:

Anaerobic bacteria do not have cytochrome systems for oxygen metabolism. Less fastidious anaerobes may have low levels of SOD and may or may not have catalase. Most bacteria of the Bacteroides fragilis group have small amounts of both catalase and SOD. There appear to be multiple mechanisms for oxygen toxicity. Presumably, when anaerobes have SOD or catalase (or both), they are able to negate the toxic effects of oxygen radicals and hydrogen peroxide and thus tolerate oxygen. Obligate anaerobes usually lack SOD and catalase and are susceptible to the lethal effects of oxygen; such strict obligate anaerobes are infrequently isolated from human infections, and most anaerobic infections of humans are caused by “moderately obligate anaerobes.”

The ability of anaerobes to tolerate oxygen or grow in its presence varies from species to species. Similarly, there is strain-to-strain variation within a given species (eg, one strain of Prevotella melaninogenica can grow at an O2 concentration of 0.1% but not of 1%; another can grow at a concentration of 2% but not of 4%). Also, in the absence of oxygen, some anaerobic bacteria grow at a more positive Eh.

Facultative anaerobes grow as well or better under anaerobic conditions than they do under aerobic conditions. Bacteria that are facultative anaerobes are often termed aerobes. When a facultative anaerobe such as E coli is present at the site of an infection (eg, abdominal abscess), it can rapidly consume all available oxygen and change to anaerobic metabolism, producing an anaerobic environment and low Eh and thus allow the anaerobic bacteria that are present to grow and produce disease.

Since the 1990s, the taxonomic classification of the anaerobic bacteria has changed significantly due to the application of molecular sequencing and DNA–DNA hybridization technologies. The nomenclature used in this chapter refers to genera of anaerobes frequently found in human infections and to certain species recognized as important pathogens of humans. Anaerobes commonly found in human infections are listed in Table 21-1.

| Genera | Anatomic Site |

|---|---|

| Bacilli (rods) | |

| Gram negative | |

| Bacteroides fragilis group | Colon, mouth |

| Prevotella melaninogenica | Mouth, colon, genitourinary tract |

| Fusobacterium | Mouth |

| Gram positive | |

| Actinomyces | Mouth |

| Propionibacterium | Skin |

| Clostridium | Colon |

| Cocci (spheres) | |

| Gram positive | |

| Peptoniphilus | Colon, mouth, skin, genitourinary tract |

| Peptostreptococcus | Colon, mouth, skin, genitourinary tract |

| Peptococcus |

1. Bacteroides—The Bacteroides species are very important anaerobes that cause human infection. They are a large group of bile-resistant, non–spore-forming, slender gram-negative rods that may appear as coccobacilli. Many species previously included in the genus Bacteroides have been reclassified into the genus Prevotella or the genus Porphyromonas. Those species retained in the Bacteroides genus are members of the B fragilis group (~20 species).

Bacteroides species are normal inhabitants of the bowel and other sites. Normal stools contain 1011 B fragilis organisms per gram (compared with 108/g for facultative anaerobes). Other commonly isolated members of the B fragilis group include Bacteroides ovatus, Bacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides vulgatus, and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Bacteroides species are most often implicated in intra-abdominal infections, usually under circumstances of disruption of the intestinal wall as occurs in perforations related to surgery or trauma, acute appendicitis, and diverticulitis. These infections are often polymicrobial. Both B fragilis and B thetaiotaomicron are implicated in serious intrapelvic infections such as pelvic inflammatory disease and ovarian abscesses. B fragilis group species are the most common species recovered in some series of anaerobic bacteremia, and these organisms are associated with a very high mortality rate. As discussed later in the chapter, B fragilis is capable of elaborating numerous virulence factors, which contribute to its pathogenicity and mortality in the host.

2. Prevotella—Prevotella species are gram-negative bacilli and may appear as slender rods or coccobacilli. Most commonly isolated are P melaninogenica, Prevotella bivia, and Prevotella disiens. P melaninogenica and similar species are found in infections associated with the upper respiratory tract. P bivia and P disiens occur in the female genital tract. Prevotella species are found in brain and lung abscesses, in empyema, and in pelvic inflammatory disease and tubo-ovarian abscesses.

In these infections, the prevotellae are often associated with other anaerobic organisms that are part of the normal microbiota—particularly peptostreptococci, anaerobic Gram-positive rods, and Fusobacterium species—as well as Gram-positive and Gram-negative facultative anaerobes that are part of the normal microbiota.

3. Porphyromonas—The Porphyromonas species also are Gram-negative bacilli that are part of the normal oral microbiota and occur at other anatomic sites as well. Porphyromonas species can be cultured from gingival and periapical tooth infections and, more commonly, breast, axillary, perianal, and male genital infections.

4. Fusobacteria—There are approximately 13 Fusobacterium species, but most human infections are caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Both species differ in morphology and habitat as well as the range of associated infections. F necrophorum is a very pleomorphic, long rod with round ends and tends to make bizarre forms. It is not a component of the healthy oral cavity. F necrophorum is quite virulent, causing severe infections of the head and neck that can progress to a complicated infection called Lemierre’s disease. The latter is characterized by acute jugular vein septic thrombophlebitis that progresses to sepsis with metastatic abscesses of the lungs, mediastinum, pleural space, and liver. Lemierre’s disease is most common among older children and young adults and often occurs in association with infectious mononucleosis. F necrophorum is also seen in polymicrobial, intra-abdominal infections. F nucleatum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree