Chapter 12 Infants and children

For convenience, we will consider five age bands:

TAKING A HISTORY

The social history is separate from but allied to the family history. It is important to understand the composition of the household in which the child lives. Include details about the parent’s occupations and whoever else is helping with child care.

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Growth

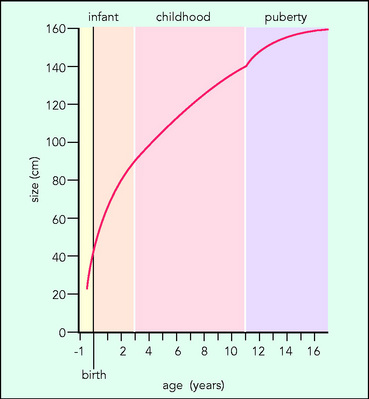

The continuum of growth from baby to adult has been described in three main phases (Fig. 12.1):

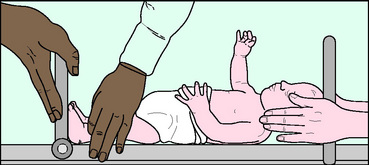

Any examination of a child is incomplete without an assessment of growth and development. It is usual to assess weight in all ages, supine length (Fig. 12.2) and head circumference in infants (under 2 years), and standing height (Fig. 12.3) in older children. Growth charts are used to help to determine the expected range at any given age.

THE NEWBORN AND VERY YOUNG BABY

Review: Gestation and weight of gestation

Review: Gestation and weight of gestation

Doctors need to know the most important signs and symptoms of serious ill health in the very young.

Examination

CIRCULATION AND CARDIOVASCULAR

Auscultation of the heart sounds and listening for murmurs may be the priority before the baby cries. Inspection of the newborn’s colour and perfusion is crucial. Peripheral cyanosis is common in the first days of the newborn period (acrocyanosis) because of vasoconstriction and relative polycythaemia (haemoglobin range 14.9–23.7 g/dl at birth): capillary refill time may therefore be more sluggish. Central cyanosis is best observed in the tongue. On inspection, the only signs of congenital heart disease may be respiratory distress at rest. A pale baby may be anaemic or even hypoxic.

ABDOMEN

Differential diagnosis: Respiratory distress

Differential diagnosis: Respiratory distress

The combination of some or all of the following:

A liver edge is usually palpable (approximately 1 cm below the costal margin).

Questions to ask: Jaundice in young babies

Questions to ask: Jaundice in young babies