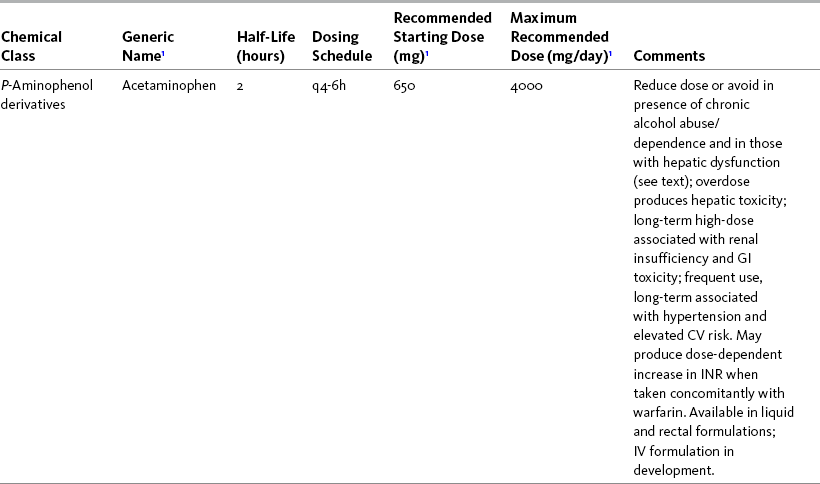

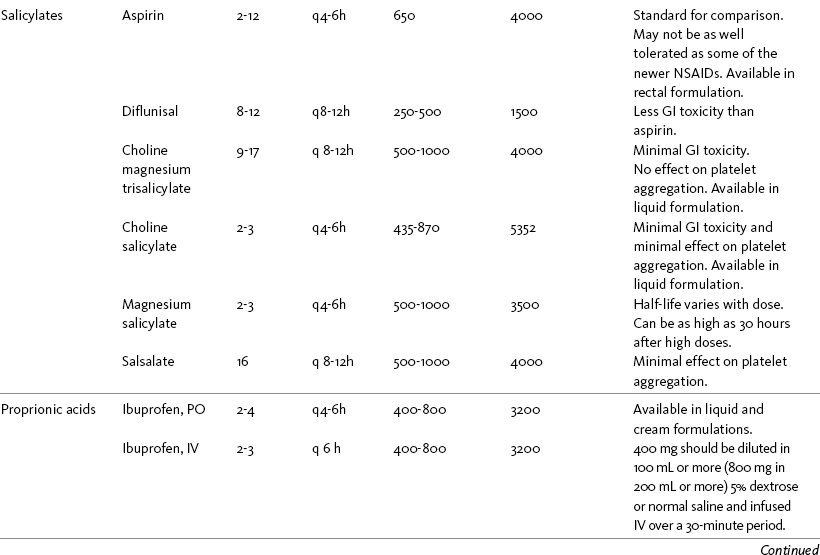

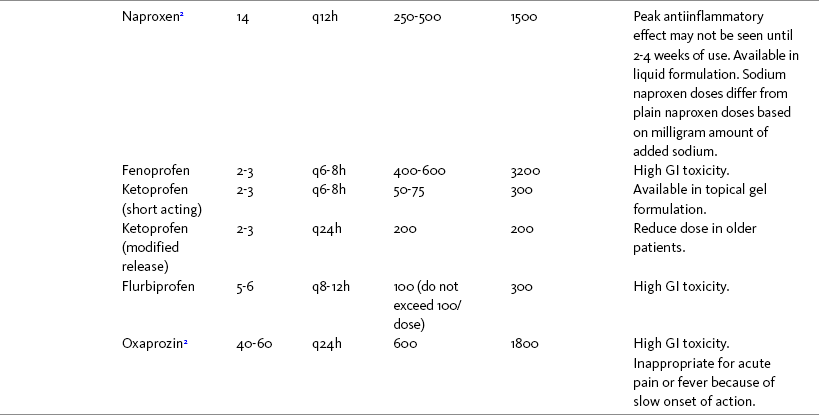

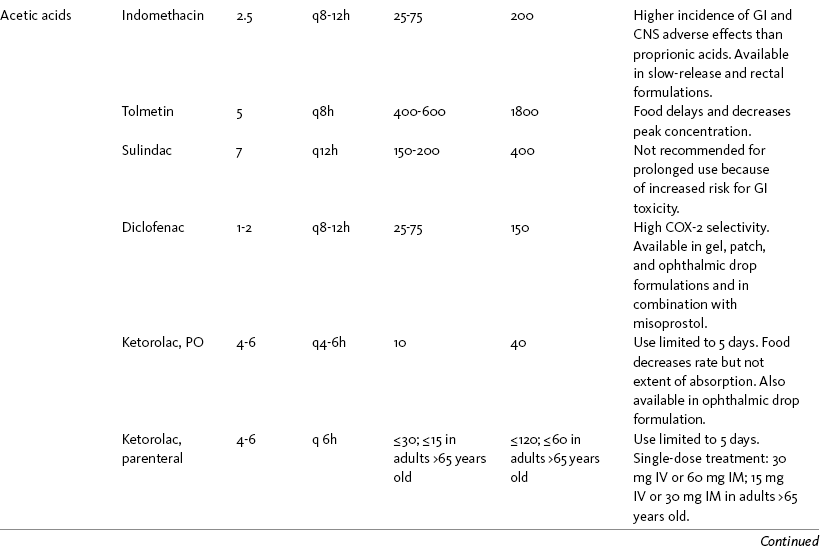

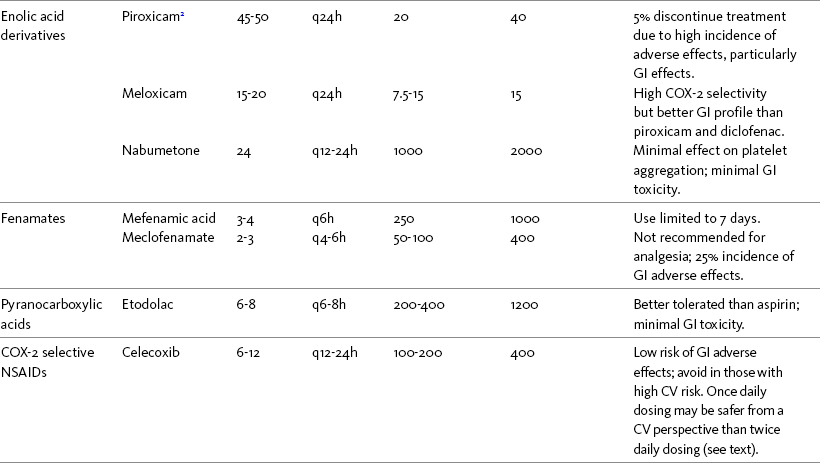

Chapter 7 THE POTENTIAL risks and benefits of nonopioid analgesic therapy should be considered in developing a plan of care for all patients with pain. Most clinicians will consider trying a nonopioid unless there is clear evidence of nonefficacy or increased risk. Once the decision is made to try one of these drugs, the goal is to select an agent and a dose that offers satisfactory pain relief with a low risk of adverse effects. Decisions about drug and dose may be influenced by the patient’s past experience, pain syndrome, and the assessed risk factors for adverse effects. The patient’s ability to pay for nonopioid therapy also should be evaluated. Table 7-1 is a guide to generic and brand names of nonopioids and may be used in conjunction with Table 7-2, which details dosing information and other characteristics for acetaminophen and NSAIDs. See Chapter 6 regarding individualizing the selection of nonopioid analgesics based on GI risk and cardiovascular (CV) risk. See patient medication information in Forms III-1 through III-5 on pp. 250-259. Table 7-1 Nonopioids Listed Alphabetically by Generic Name Followed by Brand Name From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 210, St. Louis, Mosby. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Several Cochrane Collaboration Reviews underscore the importance of evaluating the patient’s pain intensity when determining the appropriate nonopioid to administer. As mentioned earlier, acetaminophen has been shown to produce better pain relief than placebo, but NSAIDs were superior for osteoarthritis (OA) pain (Towheed, Maxwell, Judd, et al., 2006) (see pp. 220-221 for more on OA). Another Cochrane Collaboration review evaluating 51 studies and 5762 patients with moderate to severe postoperative pain concluded that acetaminophen provided effective analgesia for just half of the patients for 4 to 6 hours (Toms, McQuay, Derry, et al., 2008). These reviews support the appropriateness of acetaminophen as a first-line choice for mild pain and NSAIDs alone or in combination with other analgesics, including acetaminophen, for more severe pain. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs may be given PRN for occasional pain or around the clock (ATC) for ongoing pain. Acetaminophen has a short half-life and usually must be given every 4 hours for ongoing pain. The half-lives of NSAIDs differ, and dosing intervals range from every 4 hours to once a day (see Table 7-2). For persistent pain, the use of once or twice a day dosing usually is more convenient and more likely to result in the patient taking all prescribed doses, which will lead to better pain control. This requires an NSAID with a long half-life or one that is formulated for modified release. However, it is recommended that full doses of naproxen, piroxicam, and oxaprozin be avoided in older adults because of their long half-life and an increased risk of GI toxicity (Fick, Cooper, Wade, et al., 2003; Hanlon, Backonja, Weiner, et al., 2009) (see Chapter 6 and later discussion about half-life in this chapter). When patients are taking other analgesics or medications, consideration should be given to NSAIDs that allow for scheduling as many doses as possible at the same time. Research has shown that once-daily dosing of celecoxib may be safer from a CV perspective than twice-daily dosing, even of the same total daily dose (Vardeny, Solomon, 2008). The maximum plasma concentration of celecoxib is reached in 90 minutes after intake, and the drug has a short half-life of just 1.5 hours (Paulson, Hribar, Liu, et al., 2000). The COX-2 effect of celecoxib (and other NSAIDs) inhibits prostacyclin, a vasodilator that antagonizes platelet aggregation, and prostacyclin levels require approximately 12 hours to recover following a single oral dose of celecoxib (McAdam, Catella-Lawson, Mardini, et al., 1999). Once-daily dosing may allow enough prostacyclin recovery and normalization to attenuate any thrombotic effect (Grosser, Fries, FitzGerald, 2006; Vardeny, Solomon, 2008). Although further research is needed, the findings in other studies that utilized once-daily dosing support this theory (Sowers, White, Pitt, et al., 2005; Whelton, Fort, Puma, et al., 2001). See Chapter 6 for an extensive discussion of this and the other CV effects of NSAIDs. NSAIDs are taken most often by the oral route of administration. All NSAIDs are available orally, and a few are available parenterally, rectally, and topically. Currently in the United States the only NSAIDs available for parenteral administration are ketorolac (Toradol), ibuprofen (Caldolor), and indomethacin (Indocin). Ketorolac is widely used parenterally as an analgesic for short-term pain (e.g., postoperative), and IV ibuprofen is approved for treatment of acute pain and fever; parental indomethacin is used primarily in infants for closure of patent ductus arteriosus (Burke, Smyth, Fitzgerald, 2006). Other countries have many nonopioids available parenterally, including acetaminophen, aspirin, ketoprofen, parecoxib, and diclofenac. At the time of publication, IV acetaminophen (Acetavance) (http://www.cadencepharm.com/products/apap.html) and injectable diclofenac (Dyloject) were in development for approval in the United States (Colucci, Wright, Mermelstein, et al., 2009). An intranasal formulation of ketorolac in a disposable, metered spray device for ambulatory patients with acute pain was also in development in the United States (Brown, Moodie, Bisley, et al., 2009; Moodie, Brown, Bisley, et al., 2008). See Chapter 8 for more on these nonopioid formulations. Rectal NSAIDs are used far more often in countries other than the United States. Relatively few are available commercially for rectal administration in the United States, but most pharmacies can compound them as rectal suppositories. Oral formulations can also be administered rectally, either by using the intact tablet or by placing the intact or crushed tablet in a gelatin capsule and inserting the capsule into the rectum (Pasero, McCaffery, 1999). (Note that modified-release nonopioids should not be crushed.) Because rectal NSAIDs have an 80% to 90% oral bioavailability, higher rectal than oral doses may be required to achieve similar effects (Beck, Schenk, Hagemann, et al., 2000). (See Chapter 8 for discussion of rectal administration of perioperative nonopioids and Chapter 14 for rectal administration technique.) Although cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition is a primary mediator of NSAID analgesia by any route of administration, research is ongoing to elucidate all of the underlying mechanisms of action of topical NSAIDs. For example, in addition to COX inhibition, animal research has demonstrated that topical diclofenac inhibits peripheral NMDA (N-methyl-d-aspartate) receptors (Dong, Svensson, Cairns, 2009), and high tissue concentrations of diclofenac are capable of blocking sodium channels to mediate local anesthetic-like effects (Cairns, Mann, Mok, et al., 2008) (see Section I for more on the role of sodium channels and NMDA receptor antagonism in analgesia). The therapeutic effect of topical NSAIDs is the result of high concentrations of drug in the tissue rather than the systemic circulation (Galer, Rowbotham, Perander, et al., 2000; Mazieres, 2005; Sawynok, 2003; Stanos, 2007). The best use of topical NSAIDs, therefore, is for well-localized pain, such as arthritic joint or soft-tissue injury pain (Galer, Rowbotham, Perander, et al., 2000; McCleane, 2008). The effectiveness of a topical NSAID depends on its ability to reach the tissue generating nociception (Moore, Derry, McQuay, 2008). (See Chapter 24 for discussion of topical vs. transdermal drug delivery and Figure 24-1 on p. 685) Given their low systemic distribution, topical NSAIDs may be particularly advantageous in patients who have well-localized painful conditions that may respond to NSAID therapy but are at high risk for NSAID adverse effects, such as older adults with OA (McCleane, 2008) (see pp. 220-221 for more on OA). Patients should be advised that they may take acetaminophen concurrently but should avoid other NSAIDs while taking topical NSAIDs because this can increase the incidence of adverse effects (Galer, Rowbotham, Perander, et al., 2000; McCleane, 2008). Topical NSAIDs for Acute Pain: A systematic review of 26 double-blind, placebo-controlled trials analyzed data from 2853 patients to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a variety of topical NSAIDs for acute pain conditions, such as sprains and strains (Mason, Moore, Edwards, et al., 2004c). Compared with oral NSAIDs, topical NSAIDs provided better pain relief and similar adverse effects and treatment success. Withdrawals due to an adverse event were rare. Ketoprofen was more effective than topical ibuprofen, piroxicam, and indomethacin; there was no comparison data on diclofenac. Topical NSAIDs for Persistent (Chronic) Pain: Numerous high-quality studies have shown the superiority of topical NSAIDs compared with placebo for persistent pain (McCleane, 2008; Moore, Derry, McQuay, 2008). An extensive, systematic literature review that included 14 randomized, double-blind trials with data on over 1500 patients comparing topical NSAIDs with either placebo or other active treatment concluded that topical NSAIDs were safe and effective for persistent musculoskeletal pain (Mason, Moore, Edwards, et al., 2004c). Local and systemic effects were minimal and similar to placebo.

Individualizing the Selection of Nonopioid Analgesics

Generic Name(s)

Brand Name(s)

Acetaminophen

Tylenol, many other brand names

Aspirin

Bayer, many other brand names

Celecoxib

Celebrex

Choline magnesium trisalicylate

Choline magnesium trisalicylate

Choline salicylate

Arthropan

Diclofenac

Cataflam (short acting for acute pain), Voltaren Delayed Release, Voltaren-XR (extended release for chronic pain therapy), Pennsaid (topical drops); Voltaren topical gel, Arthrotec (combined with misoprostol), Flector (topical patch)

Diflunisal

Dolobid

Etodolac

Lodine, Lodine XL

Etoricoxib

Arcoxia

Fenoprofen calcium

Nalfon, Nalfon 200

Flurbiprofen

Ansaid

Ibuprofen

Advil, Motrin, Tab-Profen, Vicoprofen (combined with hydrocodone), Combunox (combined with oxycodone)

Indomethacin

Indocin, Indocin SR, Indo-Lemmon, Indomethagan

Ketoprofen

Orudis, Oruvail Extended-Release

Ketorolac

Toradol

Lumiracoxib

Prexige

Magnesium salicylate

Arthriten, Doan’s, Doan’s Extra Strength, Momentum

Meclofenamate sodium

Meclomen

Mefenamic acid

Ponstel

Meloxicam

Mobic

Nabumetone

Relafen

Naproxen

Aleve, Anaprox, Anaprox DS, Naprosyn, EC-Naproxyn, Naprelan, Naprapac (co-packaged with lansoprazole)

Oxaprozin

Daypro

Piroxicam

Feldene

Salsalate

Disalcid

Sulindac

Clinoril

Tolmetin

Tolectin, Tolectin DS, Tolectin 600

General Considerations

Pain Intensity

Frequency of Dosing

Routes of Administration

Rectal Nonopioid Administration

Topical NSAIDs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Individualizing the Selection of Nonopioid Analgesics

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue