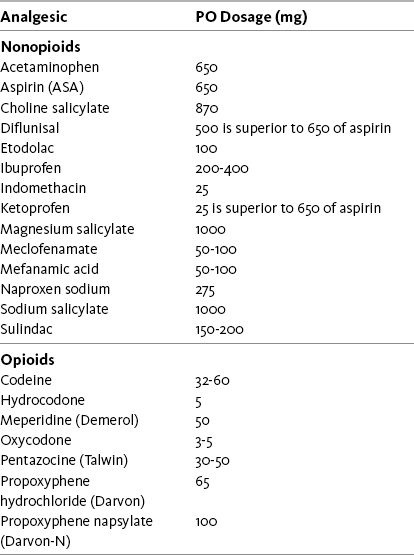

Chapter 5 NONOPIOIDS are flexible analgesics and may be used for a wide spectrum of painful conditions. Box 5-1 provides a summary of indications for nonopioids based on the discussion that follows. They typically are first-line analgesics for pain of mild to moderate intensity related to tissue injury (so-called nociceptive pain). This includes inflammatory pain following trauma or surgery, and pain caused by damage to bone, joint, or soft tissue. Given a relatively rapid onset of analgesia and the ability to initiate administration at a dose that is usually effective, it is reasonable to consider this class for both acute and persistent (chronic) pain. (See Patient Medication Information Forms III-1 through III-5 on pp. 250-259.) Acetaminophen and aspirin are equi-effective at conventionally-used doses and have long been recognized as multipurpose analgesics (Toms, McQuay, Derry, et al., 2008). As shown in Table 5-1, 650 mg of aspirin or acetaminophen may relieve as much pain as 3 to 5 mg of oral oxycodone or 5 mg of hydrocodone. Single doses of these drugs may be effective. Acetaminophen has a very low incidence of adverse effects. Aspirin is used less today because its adverse effect liability, particularly GI toxicity, is greater than most of the newer NSAIDs, and it must be taken multiple times per day to provide continuous effects. Table 5-1 From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 182, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from American Pain Society. (2003). Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain, ed 5, Glenview, IL, APS; Bradley, R. L., Ellis, P. E., Thomas, P., et al. (2007). A randomized clinical trial comparing the efficacy of ibuprofen and paracetamol in the control of orthodontic pain. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Ortho, 132, 511-517; Burke, A., Smyth, E., & FitzGerald, G. A. (2006). Analgesic-anti-pyretic agents: Pharmacotherapy of gout. In L. L. Brunton, J. S. Lazo, & K. L. Parke (Eds.), Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, ed 11, New York, McGraw-Hill; Friday, J. H., Kanegaye, J.T., McCaslin I., et al. (2009). Ibuprofen provides analgesia equivalent to acetaminophen-codein in the treatment of acute pain in children with extremity injuries: A randomized clinical trial. Acad Emerg Med, 16(8), 711-716; McCaffery, M., & Portenoy, R. K. (1999). Nonopioid analgesics. In M. McCaffery, & C. Pasero C: Pain: Clinical manual, ed 2, St Louis, Mosby; Raeder, J. C., Stein, S., & Vatsgar, T. T. (2001). Oral ibuprofen versus paracetamol plus codeine for analgesia after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg, 92(6), 1470-1472. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice. Although NSAIDs other than aspirin were originally marketed for inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), they too are increasingly used as multipurpose analgesics. Based largely on anecdotal observation, there is a strong likelihood that aspirin and other NSAIDs are relatively more effective for somatic (e.g., musculoskeletal) nociceptive pains, particularly those that involve local inflammation, than they are for other types of pain. Note that, despite having very little peripheral antiinflammatory effect, acetaminophen still may be an effective analgesic for inflammatory conditions, such as RA (Simon, Lipman, Caudill-Slosberg, et al., 2002) and postoperative pain (Schug, Manopas, 2007). As described in Chapter 7, however, there also is evidence that the nonaspirin NSAIDs are more effective than acetaminophen for the pain of osteoarthritis (OA). This has also been shown to be true for postoperative pain. A randomized controlled study demonstrated that oral ibuprofen 800 mg taken three times daily provided better pain relief than 1000 mg of oral acetaminophen taken twice daily after anterior cruciate ligament repair (Dahl, Dybvik, Steen, et al., 2004). In some situations, such as the pain associated with serious medical illnesses such as cancer, NSAIDs may be overlooked in the context of moderate to severe pain, while treatment with an opioid is initiated. In other situations, such as neuropathic pain, the likelihood that NSAIDs are relatively less effective may justify the decision to forego trials in lieu of selected drugs in the category of the so-called adjuvant analgesics (see Section V). Moderate to severe somatic pain, such as the pain associated with joint disease, usually is treated first with one of the NSAIDs. Acetaminophen and the NSAIDs are first-line analgesics for acute pain treatment and are often effective alone for mild pain and able to provide additive analgesia when combined with other analgesics for moderate to severe pain (American Pain Society, 2003; Scheiman, Fendrick, 2005; Schug, Manopas, 2007). Among the types of pain that commonly respond to a nonopioid alone are a wide variety of headaches, dental pain, and pain related to trauma or surgery. A Cochrane Collaboration Review concluded that NSAIDs and acetaminophen were similarly effective for treatment of dysmenorrhea pain, with little evidence of superiority of any of the individual NSAIDs (Marjoribanks, Proctor, Farquhar, 2003). A more recent study found that diclofenac more effectively relieved menstrual pain and improved exercise performance than placebo in healthy volunteers (Chantler, Mitchell, Fuller, 2009). The parenteral NSAID, ketorolac (Toradol), is relatively effective and often is tried for acute severe pain in the emergency department or surgical settings (see Chapters 7 and 8 for more on ketorolac). All nonopioids are conventionally used in a relatively narrow dose range, with upper titration limited either by concern about toxicity or because of pharmacologic “ceiling effect.” In the effective dose range, NSAIDs may not be adequate for severe pain but may still contribute analgesia as part of a multimodal regimen that combines drugs with different underlying mechanisms, such as nonopioids, opioids, local anesthetics, and anticonvulsants. This approach allows lower doses of each of the drugs in the treatment plan, which lowers the potential for each to produce adverse effects (Ashburn, Caplan, Carr, et al., 2004; Kim, Kim, Nam, et al., 2008; Marret, Kurdi, Zufferey, et al., 2005; Schug, 2006; Schug, Manopas, 2007; White, 2005). Further, multimodal analgesia can result in comparable or greater pain relief than can be achieved with any single analgesic (Busch, Shore, Bhandari, et al., 2006; Cassinelli, Dean, Garcia, et al., 2008; Huang, Wang, Wang, et al., 2008). (See Chapter 8 for a discussion of perioperative multimodal analgesia.)

Indications for Administration of Acetaminophen or NSAIDs

Acute Pain

Multimodal Analgesia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree