Incorporating Benefit-to-risk Determinations in Drug Development

An hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute, but a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour.

Albert Einstein’s explanation of relativity given to his secretary to relay to reporters and other lay people.

Benefit-to-risk considerations are the cornerstone of modern pharmaceutical drug development and the practice of medicine. Whether the benefit expected from taking a drug is worth the risks associated with a drug is the essential question every patient should ask. Whether a drug is able to demonstrate sufficient efficacy during the investigational period (i.e., Phases 1 to 3) to eventually have a role in clinical practice will depend on the standards used to evaluate efficacy. The author’s opinion is that the optimal set of standards to use for both efficacy and safety is to create and use minimally acceptable standards that the drug must achieve or surpass. These standards are discussed in Chapter 50 and are determined by a collaborative effort by both medical and marketing staff. Market research with physicians and patients can play a role in helping to identify these standards. Once it is known that a drug has met or surpassed the minimally acceptable standards, the benefit-to-risk balance should be positive, unless the risks are greater than anticipated.

At first glance, the concept of benefit-to-risk for a drug appears to be rather straightforward: Should a drug be prescribed and used based on the ratio or balance of its benefits to its risks for the population of patients described in the product’s labeling and, in addition, for a specific patient being seen by a physician or other healthcare professional? A closer look, however, reveals a highly complex concept that, like chaos theory, raises a whole range of new patterns and issues as one delves progressively deeper.

The positive news for those who develop drugs is that there is a simple way to study the benefit-to-risk ratio so as to incorporate continuously the impact of new data that affect benefits and risks as a drug travels the long road from test tube to market.

DEFINITIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Definitions

The best place to begin this trip is to start with some basic definitions and then to explore various stops along the route. What is meant by “benefits” and “risks”? Rather than seeking dictionary definitions, we need to ask, “Benefits and risks for whom?” The benefits (as well as the risks) of a drug are viewed in widely different contexts by different groups, in particular patients, physicians, pharmaceutical companies, Ethics Committees (ECs), data safety monitoring committees, formulary committees, consumer groups, regulatory authorities, and insurance companies (Table 77.1).

Other groups are likely to have yet different views, but these are generally less critical to the drug’s development than those listed here. Some of the ways that these groups generally conceptualize benefits and risks are briefly summarized as follows.

Perspectives

Patients

Patients view benefits in terms of whether their symptoms improve, by how much, and for how long. For drugs that prevent or suppress a disease or problem, benefits are likely to be viewed based on how well the drugs accomplish those goals according to reports they are given by their healthcare providers.

Risks are viewed as the likelihood of having adverse events, exacerbations or new episodes of their underlying disease, or other drug-related problems. Risks that a patient voluntarily accepts (e.g., smoking cigarettes while using oral contraceptives) are often differentiated from those where little or no choice is possible (e.g., cosmic radiation while walking down the street by one’s home). Some risks that are accepted involve elements that are both voluntary and involuntary (e.g., driving a car for one’s business).

Patients also assess their own treatment in terms of quality of life and compliance factors in order to decide whether their current treatment is better or worse than previous treatments. Their assessments are usually discussed with their physician and usually influence the physician’s benefit-to-risk judgment about how to continue to treat that specific patient. Two patients experiencing the same benefits and risks may react quite differently to the risks. For example, one patient may decide to forego the benefits rather than to risk the adverse events, whereas another patient may reach the opposite conclusion. The benefit-to-risk ratio of the drug would, therefore, be different for these two patients. This trade-off is illustrated in Figure 65.6.

Table 77.1 Stakeholders in benefit to risk | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physicians

Physicians view benefits of a drug in relative terms. They assess or guess whether other doses, other drugs, or a nondrug treatment will enhance or reduce the degree or type of benefit their patient is experiencing or potentially could experience. Risks of a drug may sum in a complex way with concomitant drugs being used, and the resulting risk is often difficult to predict. In addition, a drug may increase the risk of serious adverse events resulting from the drug, but at the same time, the drug might decrease the risks attributable to the disease being treated. This is a frequent trade-off experienced by physicians in emergency care medicine.

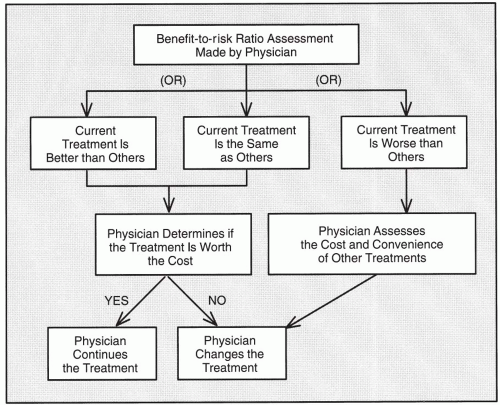

Overall, a physician must determine the benefit-to-risk ratio for a patient by considering all benefits and risks and then comparing the present treatment with previous treatments, other treatments, or no treatment at all. The risks a physician should assess are both the real risks and the perceived risks that may or may not be real. To make this assessment, the physician needs to have access to current literature. The physician must then decide whether the current treatment is better than, the same as, or worse than one or more of the other treatments available (Fig. 77.1). If the current treatment is better or about the same, the physician must evaluate whether it is worth the cost in money, convenience, and other factors such as any paperwork or administration required (e.g., if an Investigator Investigational New Drug Application is required). If the current treatment is worse than others, the physician must evaluate the convenience and cost of each of the other alternative treatments that may be preferable.

Number Needed to Treat

The most objective way for a physician to evaluate benefits and to compare the benefits of different treatments is in terms of the number of patients needed to be treated for a specified period to obtain one beneficial response. This concept has been described as the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT is the reciprocal of the difference in the rate of the benefit between the treated group and control group (i.e., the reciprocal of the absolute risk reduction). This concept was described by Laupacis, Sackett, and Roberts (1988) and has been widely used not only to describe benefits but also risks, which are described as the number of patients needed to receive a treatment for a specified period that will result in one patient being harmed [i.e., number needed to harm (NNH)].

Pharmaceutical Companies

Pharmaceutical companies view a drug’s beneficial properties in terms of its ability to demonstrate sufficient efficacy so that:

Regulatory authorities will approve their product

Third-party payers will reimburse for the drug

Physicians will prescribe the drug

Patients will purchase and use the drug

Risks are usually viewed as adverse events (including abnormal vital signs, symptoms, laboratory abnormalities, physical abnormalities, and other clinical signs) relative to existing treatments. Companies may accept the presence of increased risks until they reach the point where regulatory authorities will not approve the drug or physicians will not prescribe it. Within a company, some groups traditionally tend to focus to a greater degree on these risks (e.g., attorneys, research and development staff), while others tend to focus primarily on benefits (e.g., marketers, public relations, advertising staff). Obviously, these are generalizations with many exceptions.

A pharmaceutical company must focus on the interests of all groups concerned with benefits and risks. To obtain a more complete concept, a company must determine the benefit-to-risk ratio for the following:

Indications being developed. Each indication may be the basis for a greatly different benefit-to-risk ratio. For example, there may be large differences in the doses needed to benefit patients with one indication versus another, and patients exposed to larger doses may have greater risk from adverse events. However, even the same dose may have different risks of adverse events in patients with one disease versus another (e.g., the risk to women with child-bearing potential taking thalidomide versus men taking the same dose).

Dosage forms and route(s) of administration being developed. Each dosage form of a drug has its own benefit-to-risk ratio. These ratios may be similar or entirely different. One example is busulfan; when used as part of the chemopreparative regimen for a bone marrow transplant, busulfan frequently causes emesis when given orally. If the dose is repeated because of emesis, it may cause severe adverse events due to its very narrow therapeutic index. However, by giving the drug intravenously, one avoids gastric irritation and, thereby, diminishes the incidence of emesis, making the benefit-to-risk ratio much more favorable.

Levels of patients evaluated. The benefit-to-risk ratio may be considered for different categories of patients. In this example, three levels are considered: the individual patient, a group of patients, and all patients with the disease.

An individual patient with the disease. A physician evaluates individual patients to decide whether to continue, stop, or modify the dosing, dose level, and dose schedule of a specific drug. This is usually based on the physician’s assessment of the benefit-to-risk ratio for a specific patient.

Groups of patients with the disease. Formulary committees or other bodies decide which drugs to include on their formulary based on their benefit-to-risk ratio as well as their cost in a group of patients. Formulary committees include the committees of hospitals, provinces, Health Maintenance Organizations, insurance companies, and other groups, all of which assess benefits and risks for patients in their specific organizations. The assessment of types and magnitude of benefits and risks for a single drug is likely to vary widely among organizations, at least for certain drugs (e.g., those with marginal benefits and increased costs, those that are extremely expensive).

All patients with the disease. Certain national agencies or foundations for research make decisions about awarding grants to individual scientists and groups developing new drugs (e.g., in oncology) based in part on the perceived benefit-to-risk ratios of those drugs. Legislators and administrators also use these ratios when deciding how to apportion money to purchase drugs and other treatment modalities. For example, the ratios may guide

decisions in a state or other locality about whether to provide prenatal care for X number of pregnant women as opposed to funding Y number of liver transplants.

In evaluating this concept over time, it is obvious that the benefits expected at the start of a drug’s development often vary greatly from those found as additional data are collected. Similarly, projected benefit-to-risk ratios at the start of a drug’s development often have little resemblance to those observed after the drug reaches the market. Thus, the concept of benefit to risk is a very dynamic one that is subject to great changes over time.

During the marketing period, the benefit-to-risk ratio sometimes changes as new information is gathered. Such changes may be gradual or sudden. Thus, it makes little sense to believe that the benefit-to-risk ratio on the first day of marketing when it is based on data from only a few thousand patients at best will be the same when several hundred thousand or millions of patients have used the drug. Of course, the ratio may improve (as it did for many drugs of the statin class), or it may remain the same (as it does for the majority of drugs) or decrease to the point where the drug’s use is restricted or it is removed from the market.

Technical Risks of Developing Drugs

Also, the pharmaceutical company considers that each drug has a technical risk of failure in development, expressed as the probability of its reaching the market. This, in turn, depends in part on the phase of development (i.e., how close it is to the market). Generally, the more advanced a drug is, the greater the likelihood of its being approved and launched. The technical risk also depends on whether the scientific rationale for using the drug is based on strong or weak preclinical data and on how well those data can be extrapolated to humans.

Intellectual property (patents), licensing, and competitive issues are also risks for the pharmaceutical manufacturer throughout the life of a drug.

Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committees

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs)/ECs view benefits and risks in terms of the acceptability for patients to enter a clinical trial to evaluate new or marketed drugs. These committees also must consider the benefits and risks of using a placebo or active treatment if one is included in the trial design.

IRBs/ECs usually focus on the benefits and risks of the activities described in the protocol. They do not generally evaluate a trial to determine the sins of omission, that is, whether procedures or other activities not included should be or whether the data to be obtained justify the benefits and risks of the trial. For example, are there too few patients to be enrolled to provide statistically and clinically meaningful results when the trial is completed? Are the endpoints measured going to provide the most meaningful results that are possible in this particular trial? Is the trial open-label or double-blind? Many other such questions could be posed but rarely are, particularly if there is no statistician or clinical trial methodologist on the IRB/EC. The author believes that these and also other related methodological questions should be posed by every IRB of every clinical trial protocol because patients may be at risk because of what is not included in the trial (e.g., sufficient power to show an effect if it is there, adequate trial design that minimizes biases and confounding factors, using a double-blind procedure instead of an open-label one) as well as what is included. This is because a trial that will not yield meaningful data is unethical to conduct and should not place patients at risk.

Data Safety Monitoring Boards

Data Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMBs; sometimes referred to as independent data monitoring committees) view benefit to risk in terms of the rules that have been established in advance for terminating a trial on futility grounds (i.e., inability to demonstrate efficacy if the trial continues to completion) or for reasons of safety that show increased levels of clinically significant adverse events in the treatment group compared with the control. Trials are also able to be stopped for overwhelmingly positive efficacy that achieves a preset “p” value demonstrating a major positive response. It should be noted that a DSMB may only be constituted to assess safety, and the efficacy issues mentioned may not be in their remit. DSMBs are discussed in Chapter 81.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree