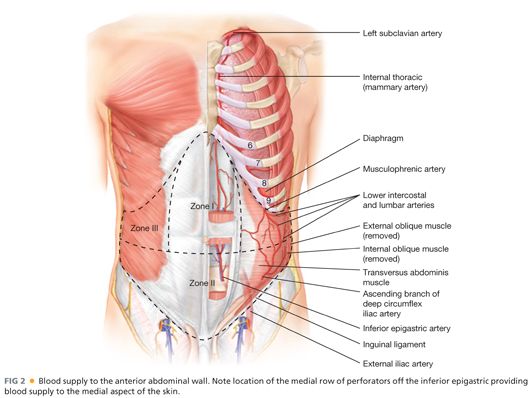

■ The blood supply of the anterior abdominal wall is slightly more complex (FIG 2). The rectus muscle receives its blood supply both laterally from the intercostal vessels and from a superior and inferior branch of the inferior epigastric vessel. The blood supply to the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the midline is also important to understand to limit ischemic problems during reconstruction. The skin does receive some limited supply from the lateral intercostal vessels, but the majority comes from deep inferior epigastric perforator vessels. These vessels typically lie within 5 cm cephalad and caudad to the umbilicus. This relationship is particularly useful when performing a periumbilical perforator sparing component separation.

Positioning

■ Regardless of the abdominal wall reconstructive technique chosen, some basic technical aspects remain constant. A wide surgical preparation including the entire abdomen, lower chest, and upper legs is performed with a chlorhexidine solution. All stoma sites are oversewn to minimize spillage. An iodine-impregnated dressing is routinely applied to cover the entire abdominal wall.

TECHNIQUES

INCISION

■ The surgical incision is typically performed in a midline fashion and all other old scars or skin ulcerations are completely excised.

ADHESIOLYSIS

■ The abdominal cavity is entered and a complete adhesiolysis is performed to free up the entire abdominal wall all the way to the gutters. This step is critical, as the abdominal wall will be limited in its mobility if it remains fixated to the viscera.

CONCOMITANT PROCEDURES AND REMOVAL OF ALL FOREIGN MATERIAL

■ Any concomitant GI surgery is completed and all prior synthetic material is removed from the abdominal wall. In our opinion, removing prior synthetic material allows the new prosthetic to actually grow into the abdominal wall and reduces seromas and mesh infections. After the intraperitoneal portion of the procedure is completed, a countable towel is placed over the abdominal viscera to prevent inadvertent injury during dissection of the abdominal wall.

POSTERIOR COMPONENT SEPARATION TECHNIQUE

■ A posterior component separation is basically an extension of the standard Rives-Stoppa-Wantz repair.

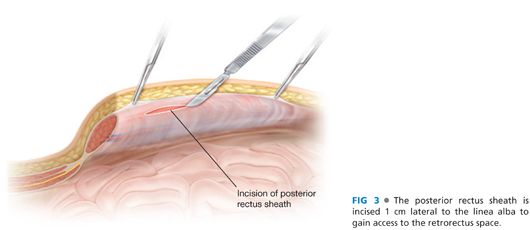

■ The initial procedure begins in a similar fashion. The linea alba is identified and grasped with Kocher clamps. To avoid confusion and misidentification of appropriate planes, the clamps must be placed on the medial edge of the rectus muscle and not on the hernia sac. If the clamps are on the hernia sac, the dissection will proceed in a subcutaneous plane. Next, an incision of the posterior sheath is made approximately 1 cm off the linea alba. It is important to identify the rectus muscle, which will avoid creating a subcutaneous or preperitoneal plane of dissection (FIG 3).

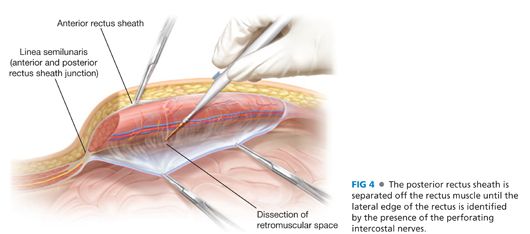

■ The posterior rectus sheath is then separated off the rectus muscle using electrocautery, carefully preserving the inferior epigastric vessel. This dissection plane is facilitated by placing upward traction on the rectus muscle and medial traction on the posterior sheath with Kocher clamps. Typically, small posterior branches off the epigastric vessels can be coagulated.

■ The lateral extent of this dissection continues until the perforating intercostal nerves and vessels are identified. These nerves as mentioned are critical to preserve to maintain a functional innervated rectus muscle. They also are the landmark of the linea semilunaris, that is, the lateral extent of the rectus muscle. In a standard Rives-Stoppa-Wantz repair, the dissection is completed at this point (FIG 4).

■ If more advancement is needed to provide mobilization for the posterior sheath or anterior sheath, or provide a larger compartment for an adequate-sized piece of mesh, then a posterior component separation is performed.

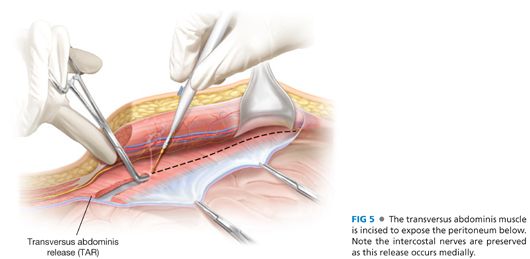

■ This dissection is usually started in the upper third of the abdomen. In this location, the transversus abdominis muscle actually forms the posterior sheath and does extend medial to the linea semilunaris. The incision is begun approximately 0.5 cm medial to the intercostal nerves. The initial incision should involve the fascial covering of the muscle, and it is extended throughout the length of the posterior rectus sheath. When performing this release, it is always important to confirm that it is not disrupting the intercostal nerves.

■ Next, the transversus abdominis muscle is released medial to the linea semilunaris. This is facilitated by the use of a right-angle clamp in the upper third of the abdomen under the muscle (FIG 5). Below this muscle is the peritoneum and can be quite thin on the medial side.

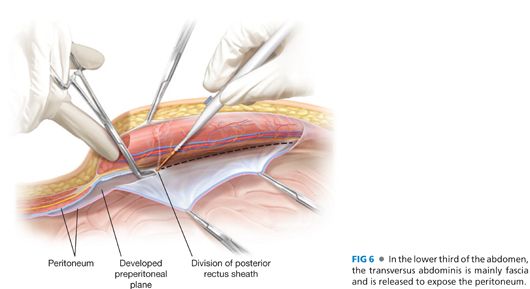

■ As the dissection continues caudally, the muscle belly of the transversus abdominis is replaced with a fascial layer. This layer is also incised, leaving the transversalis fascia and peritoneum in the lower third of the abdomen (FIG 6).

■ Once the entire transversus abdominis is released, the dissection is continued laterally. Again, this dissection plane is below the transversus abdominis muscle and above the peritoneum/retroperitoneum. The lateral extent of this dissection is the lateral edge of the psoas muscle. This plane can be extended cephalad to the costal margin, sweeping the peritoneum off the diaphragm.

■ The posterior sheath is incised at its insertion into the linea alba to connect each side of the abdomen. This is continued at least 5 cm above the incision and typically can be performed to the xiphoid process. In upper abdominal hernias, the insertion of the posterior sheath is released from the xiphoid, and the dissection is continued to the fatty triangle underneath the sternum and toward the central tendon of the diaphragm.

■ Inferiorly, the bladder is separated off the anterior abdominal wall. In suprapubic hernias, the pelvis is exposed, including the pubis, Cooper’s ligaments, and the space of Retzius.

■ The posterior sheath, peritoneum, and transversalis fascia are reapproximated in the midline, completely excluding the mesh from the bowel. Any fenestrations are sutured closed. In cases of large defects of the posterior sheath, Vicryl mesh can be used.

■ It is very important that the posterior sheath is closed safely because bowel can herniate through the posterior closure and become incarcerated below the mesh.

■ A large sheet of unprotected medium-weight large-pore polypropylene mesh is typically placed in the retrorectus space.

■ Several transfascial sutures are placed at the lateral edge of the mesh. The sutures are placed under tension so as to allow the midline closure to be off weighted. These sutures also set the tension on the mesh that prevents buckling when the midline is closed over the mesh (FIG 7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree