Familial Hypercholesterolemia due to Mutations in the LDL Receptor

Mutations in the LDL receptor gene (LDLR) are the most common cause of familial hypercholesterolemia (Case 16). The receptor is a cell surface protein responsible for binding LDL and delivering it to the cell interior. Elevated plasma concentrations of LDL cholesterol lead to premature atherosclerosis (accumulation of cholesterol by macrophages in the subendothelial space of major arteries) and increased risk for heart attack and stroke in both untreated heterozygote and homozygote carriers of mutant alleles. Physical stigmata of familial hypercholesterolemia include xanthomas (cholesterol deposits in skin and tendons) (Case 16) and premature arcus corneae (deposits of cholesterol around the periphery of the cornea). Few diseases have been as thoroughly characterized; the sequence of pathological events from the affected locus to its effect on individuals and populations has been meticulously documented.

Genetics.

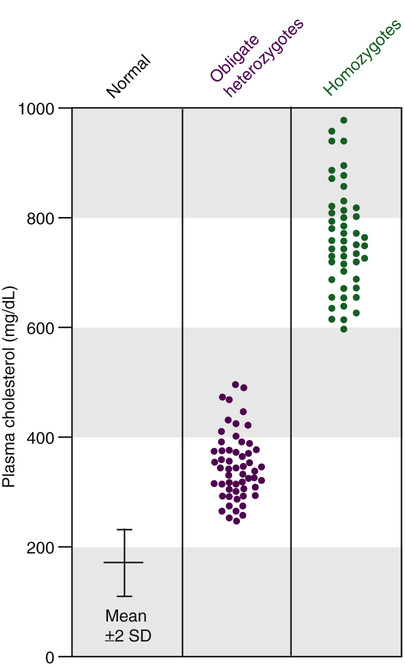

Familial hypercholesterolemia due to mutations in the LDLR gene is inherited as an autosomal semidominant trait. Both homozygous and heterozygous phenotypes are known, and a clear gene dosage effect is evident; the disease manifests earlier and much more severely in homozygotes than in heterozygotes, reflecting the greater reduction in the number of LDL receptors and the greater elevation in plasma LDL cholesterol (Fig. 12-13). Homozygotes may have clinically significant coronary heart disease in childhood and, if untreated, few live beyond the third decade. The heterozygous form of the disease, with a population frequency of approximately 2 per 1000, is one of the most common single-gene disorders. Heterozygotes have levels of plasma cholesterol that are approximately twice those of controls (see Fig. 12-13). Because of the inherited nature of familial hypercholesterolemia, it is important to make the diagnosis in the approximately 5% of survivors of premature (<50 years of age) myocardial infarction who are heterozygotes for an LDL receptor defect. It is important to stress, however, that, among those in the general population with plasma cholesterol concentrations above the 95th percentile for age and sex, only approximately 1 in 20 has familial hypercholesterolemia; most such individuals have an uncharacterized hypercholesterolemia due to multiple common genetic variants, as presented in Chapter 8.

Cholesterol Uptake by the LDL Receptor.

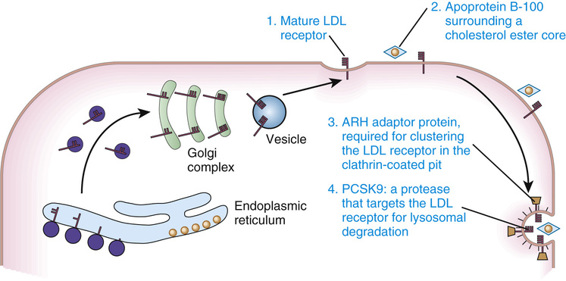

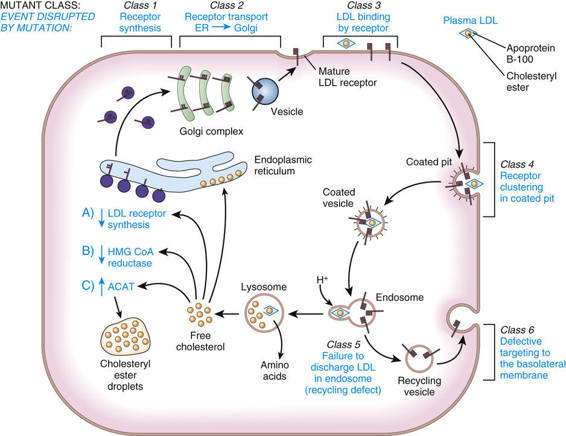

Normal cells obtain cholesterol from either de novo synthesis or the uptake from plasma of exogenous cholesterol bound to lipoproteins, especially LDL. The majority of LDL uptake is mediated by the LDL receptor, which recognizes apoprotein B-100, the protein moiety of LDL. LDL receptors on the cell surface are localized to invaginations (coated pits) lined by the protein clathrin (Fig. 12-14). Receptor-bound LDL is brought into the cell by endocytosis of the coated pits, which ultimately evolve into lysosomes in which LDL is hydrolyzed to release free cholesterol. The increase in free intracellular cholesterol reduces endogenous cholesterol formation by suppressing the rate-limiting enzyme of the synthetic pathway, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG CoA) reductase. Cholesterol not required for cellular metabolism or membrane synthesis may be re-esterified for storage as cholesteryl esters, a process stimulated by the activation of acyl coenzyme A : cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT). The increase in intracellular cholesterol also reduces synthesis of the LDL receptor (see Fig. 12-14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree