Chapter 11

Implications of Multimorbidity for Health Policy

Chris Salisbury1 and Martin Roland2

1Centre for Academic Primary Care, NIHR School for Primary Care Research, School of Social and Community Medicine, University of Bristol, UK

2University of Cambridge, The Primary Care Unit, Institute of Public Health, UK

Overview

- A large and increasing proportion of the population have multimorbidity, yet healthcare systems are designed as if people have only one problem at a time

- Attempts to redesign health care to reflect the needs of patients with multimorbidity would have wide implications for how we organize the system at national, regional and local levels

- Changes include valuing generalism as much as specialism, avoiding fragmentation of primary care, ensuring greater relational continuity of care, investment in shared electronic record systems and balancing vertical integration of care across primary/secondary care for individual diseases with horizontal integration of care for people with multiple diseases

- Research is needed to test new models of healthcare organization designed to address the needs of people with multimorbidity.

Background

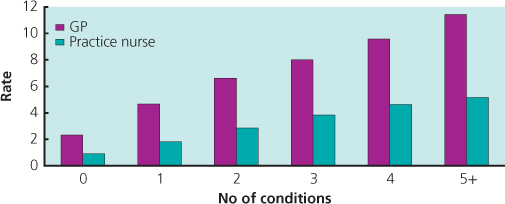

As we have seen in the previous chapters, multimorbidity is common and its prevalence is strongly related to age. As the population ages, the number of people with multimorbidity in the population is increasing. The number of times that people consult doctors is associated with the number of health problems they have, so people with multimorbidity account for a high and increasing proportion of all consultations in primary care (Figure 11.1). In one recent study (Salisbury et al. 2011), 16% of people registered with GPs had more than one of the chronic conditions included in the English Quality and Outcomes Framework, but they accounted for 32% of all general practice consultations.

Figure 11.1 Number of consultations in general practice per year by number of chronic conditions included in the Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Many consultations in primary care therefore involve people who have multimorbidity. It is also recognized that most consultations in general practice involve the discussion of several different problems. Typical consultations in the UK general practice included discussion of an average of 2.5 different problems and several associated issues across a wide range of disease areas (Salisbury et al. 2013). And yet medical care, particularly in hospital, tends to be organized as if people have only one disease at a time.

There has been a long-term trend for health care in hospitals to become increasingly specialized. There is now a similar trend in general practice towards organizing care within specific disease domains. As a means of improving the quality and consistency of care for individual conditions and to improve integration across primary and secondary care, attention has been given to creating ‘disease pathways’ for common chronic conditions. Processes of ideal care are clearly mapped out and protocols developed to ensure that care is systematic, efficient and coordinated. In general practice, patients are invited to specific appointments during which their chronic condition, such as diabetes or asthma, is reviewed. They often see practice nurses who have extra training in that condition and who provide care following computerized disease-specific templates based on national guidelines. The disease pathway approach seeks to improve integration of services across primary and secondary care; for example, through shared records, liaison nurses and shared protocols for care.

Therefore, there is a tension between these two opposing trends – most medical care involves managing patients with multimorbidity, and yet it is increasingly organized within single-disease pathways (Box 11.1).

Problems of the single-disease paradigm for patients

From a patient’s point of view, care provided along single-disease lines is inconvenient because it often involves attending different

Box 11.1

What are the consequences of the tension between increasing specialization within primary care and the rising prevalence of multimorbidity for patients and for the healthcare system?

What would be the implications for policy of trying to design health care to suit the needs of the people who need and use it most – that is, people with multimorbidity?

clinics to discuss each of their problems. At these clinics, health professionals focus on optimizing care for one disease, which may not be the patient’s top priority. Patients find it frustrating to be repeatedly asked the same questions by different health professionals, who do not seem to be very aware of their other problems and appointments, and then to be given conflicting advice (Bayliss et al. 2008) (Box 11.2).

Box 11.2 What do patients say they want?

- Better access to care by phone, email and face-to-face

- A single coordinator of care

- Continuity of care from a limited number of healthcare professionals

- Clear communication of a care plan

- Healthcare professionals to listen to and take account of their own individual needs

- Not to have protocols inflexibly applied to them

If each disease is treated in isolation, patients risk being subjected to more and more interventions each time they attend a disease-specific appointment. In order to gain optimal disease control, additional drugs may be prescribed, patients may be given other non-drug advice (such as specific exercises) and may have additional blood tests and other investigations. For people with multiple long-term conditions, this has the potential to lead to a level of intervention which is excessively complex and burdensome. Decisions often need to be made about the most important priorities, and this is difficult to do in the context of single-disease clinics. Making these judgements can be difficult as evidence about the benefits of particular treatments in patients with multimorbidity is often lacking.

However, it is important to remember how this situation has evolved. The development of guidelines, templates and clinics for conditions such as diabetes occurred because of evidence that quality of care for patients with long-term conditions was variable and sometimes poor. The introduction of these systems, incentivized by pay for performance schemes such as the Quality and Outcomes Framework in the UK, has probably helped to drive up quality and reduce inequalities in care. And although we know that patients express a desire for more holistic care from a known and trusted doctor, they express an even stronger wish to have a thorough examination and to see a professional with expertise in their health condition. So is there a way of maintaining the benefits of systematic organized care, without losing the personal care and sense of being treated as a ‘whole patient’ that patients value?

Implications of multimorbidity for the healthcare system

A systems approach to the management of long-term conditions

Considerable attention has been paid to the importance of a whole-system approach to improving the management of chronic disease. The chronic care model (Epping-Jordan et al. 2004) has delineated a range of important factors which need to be addressed to promote effective management of chronic disease. This highlights that in order to improve care, we must not only seek to enable patients to manage their own health better through individual consultations but also ensure that structural changes are effected; for example, in how care is provided and through improved decision support and information systems.

Integrating primary and secondary care

It is widely recognized that healthcare systems that provide effective and efficient care for people with long-term conditions need to have a strong primary care foundation, which provides easily accessible generalist care and a gateway to specialist care. The important coordinating role of primary care, with judicious use of specialists, is particularly relevant to patients with multiple chronic conditions because of the risk of over-investigation and over-treatment.

However, the disadvantages of a rigid, structural divide between generalist primary care and specialist secondary care have been increasingly recognized. Primary care practitioners need easier access to specialist advice about individual patients. Specialists also have an important role in providing training, protocol development and system design. These developments are hindered by financial systems which lead to competition between primary and secondary care and create inappropriate incentives to treat patients in the wrong setting, especially if there are financial incentives on general practitioners to limit referrals to specialist care.

Promoting continuity of care

It is likely to be more efficient and more acceptable to patients if a limited number of doctors and nurses working in a small team see people with complex problems. This will increase the likelihood that the healthcare providers will be able to make decisions with a good understanding of the patient’s situation and other problems and priorities. It also promotes the development of trust between patients and professionals, which is associated with greater patient satisfaction and increased adherence to treatment recommendations.

On the other hand, it is challenging for an individual clinician to be an expert in a wide range of conditions. This model of continuity from a small number of multi-skilled primary care professionals requires investment in decision support systems to prompt clinicians to provide care of consistently high quality, backed by audit systems to ensure that this quality is maintained. It also requires a careful judgement about which things are best managed by generalists (arguably, conditions which are common, such as asthma, hypertension and depression), which are better managed by specialists (those which are rare or require facilities not economically provided in the community) and which require coordination by a generalist but with occasional intervention from specialists for specific purposes (e.g., intensive short-term intervention by a specialist nurse for a patient with poorly controlled diabetes).

We know that many patients value continuity of care, but continuity is also important for reasons that patients may not appreciate. It is particularly important for patients with multiple problems: such patients are very difficult to manage in short general practice consultations if the doctor does not have prior knowledge of the patient. For these patients, continuity of care is likely to lead to better use of healthcare resources, because in a fragmented system each new doctor tends to repeat investigations ‘just in case’, and continuity is also likely to lead to more appropriate judgements about diagnosis and treatment. Most importantly, patients with multimorbidity need a single, clearly designated healthcare professional who is accountable for coordinating their overall management, and this requires continuity of care.

Avoiding fragmentation of primary care

It is important that patients with multimorbidity have a single point of access to the healthcare system for most of their problems, most of the time. In many countries, people have direct access to specialists. This can be advantageous for people with single, well-defined problems. But for people with multimorbidity, this is likely to lead to poorly coordinated care. Because each specialist provider cannot address all of their problems, patients with multimorbidity frequently have to be cross-referred to other providers.

Within primary care, recent policies in many countries have encouraged the development of new types of providers of primary care with the aim of promoting patient choice, encouraging competition between providers and improving access to health care. For example, the NHS in the UK has introduced walk-in centres, which offer nurse-led advice and treatment without an appointment. However, this type of care can be inefficient because of duplication of effort, leading to poor coordination of care, undermining the development of trusting relationships with health professionals and risking confusion for patients (Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2 Multiple sources of care can be confusing and risks duplication.

We should recognize that these multiple providers have often arisen because of deficiencies in the service provided by general practices, particularly in terms of access to care. However, it is likely to be more effective and efficient to improve access to general practice than to develop multiple alternative providers.

There may be benefits from having multiple providers of primary care in terms of improving access to care, but these benefits need to be balanced against a reduction in continuity and coordination of care. The balance between these advantages and disadvantages may be different for different groups of the population. For example, young people with few previous health problems, who rarely consult doctors and have busy working lives, may appreciate the convenience of walk-in centres. But the people with the biggest health needs are those with multimorbidity, and they are disadvantaged by a policy of investment in multiple new sources of care rather than in improved provision from a single, local, healthcare provider who is able to provide first contact generalist care for all their problems in one place and at one time.

Shared records

To some extent, the problem of patients with multimorbidity attending different specialists for each of their problems can be reduced if all the different healthcare providers have a shared system of electronic medical records. Achieving this should be a high priority for any health system that seeks to provide integrated care for people with multimorbidity, so that each care provider can take account of investigations and treatments provided elsewhere. However, the difficulties of creating a system of shared records should not be under-estimated, given the very different record-keeping needs of the different types of healthcare professionals and provider organizations within a large and complex healthcare service. Furthermore, although shared records are likely to be very important in order to promote coordination of care, it should not be assumed that a so-called ‘information continuity’ is a substitute for personal, relational, continuity with a known and trusted clinician.

Promoting generalist skills

If patients are able to attend one healthcare facility as the first point of contact for almost all of their health problems and if it is important to encourage continuity of care from a small number of professionals, it follows that these professionals must have an understanding of a wide range of diseases, a broad range of skills and an ability to make complex judgements when faced with multiple considerations (e.g., a patient with diabetes and asthma who does not adhere to medication because they are depressed and sees no point in living to an old age and whose breathing is made worse by poor housing). These healthcare professionals need to have a sophisticated understanding about the relationship between these physical, psychological and social factors as they make decisions about diagnosis and treatment and have an attitude that focuses on the overall needs of the patient rather than on abstract notions of ideal disease control.

Training doctors and nurses

In training doctors and nurses, more recognition needs to be given to the fact that most patients they see will have multimorbidity rather than a single disease. Students need to learn more about the key factors highlighted by the chronic care model, such as promoting patient self-management (rather than assuming that doctors make decisions and patients do as they are told), the need for individual accountability in coordinating the care of complex patients and the importance of organizational factors such as recall and reminder systems. Most importantly, students need to be encouraged to develop a patient-centred attitude rather than a disease-centred attitude and an approach to consulting which is based on understanding the patient’s context, sharing decisions with them and reaching an agreement about an individual management plan that reflects their priorities.

Valuing generalism

At a national level, healthcare systems need to value and promote careers that are based on generalism rather than specialism. This may be reflected in the involvement of generalist doctors in national decision-making bodies, the length of training that is deemed necessary for the role and the salaries of generalists versus specialists. In many countries, generalists earn less than specialists, and it is not surprising that in these countries it is difficult to attract the best doctors and nurses to work in generalist roles.

Planning and commissioning healthcare

Commissioners of health care seek to redesign care pathways in order to obtain the best outcomes at the lowest cost. As previously discussed, these care pathways are frequently designed on a disease-specific basis. Services are often commissioned from specific providers for an individual disease, and the performance of these providers is often monitored in terms of disease-specific targets. This can again lead to fragmentation of care. Therefore, when planning and commissioning services for individual diseases, it is important to ensure that providers can as far as possible manage common comorbidities without cross-referral and that they can communicate information effectively with the primary care professional who is coordinating the patients’ overall care.

Clinical guidelines

In most developed countries, guidelines have been developed for the management of chronic diseases. The authors of guidelines need to be explicit about the extent to which these are valid for patients with comorbidities. In some cases, there may be little or no evidence about the management of patients with comorbidities on which to base guidance. It cannot be assumed that interventions are equally beneficial in patients with comorbidities as in those without. For example, a patient with cancer or heart failure has a reduced life expectancy and may have less to gain from interventions that are designed to increase their life span but at the expense of drug side-effects in the short term.

On the other hand, in the absence of evidence from patients with multimorbidity, guidelines based on patients with a single condition may be all we have to go on. It is arguable that the benefits of treatment may be even greater in patients with multimorbidity because they are at a greater absolute risk of adverse consequences of disease and therefore have most to gain from interventions.

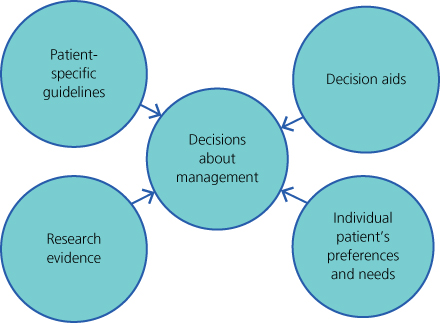

The solution to this dilemma is not necessarily a nihilistic rejection of guidelines. Instead, it may mean that we need more sophisticated guidelines and targets that carefully define the target population and take account of comorbidities. For example, blood pressure targets may need to be more relaxed for patients who have a reduced life expectancy due to a non-cardiovascular condition but conversely more strict for patients with other conditions such as renal or eye disease, which are more progressive in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. These patient-specific guidelines should be combined with decision aids to inform management decisions that reflect the evidence and also the individual patient’s preferences and needs (Figure 11.3). It is important to allow professionals to exclude individual patients from targets when there are particular reasons why achieving the target may be inappropriate or impossible; for example, because the patient makes an informed choice not to follow the guidance.

Figure 11.3 Factors that should be fed into treatment decisions about individual patients.

New approaches to research are needed

Guidance is at least partly based on research evidence, but much research that underpins guidelines excludes or fails to take account of patients with multimorbidity. There are clear parallels with research which in the past routinely excluded patients aged over 75, yet the findings were used to make decisions about the care of elderly patients. In future, research on interventions should include the broad range of patients to whom they are likely to be applied, including those with multimorbidity. There should be an explicit plan to compare the effectiveness of the intervention in patients with and without comorbidities. This will inevitably make trials larger and more costly as they will need to be more inclusive and large enough to allow for subgroup analysis. For research that is already published, the problem may be addressed to a degree by meta-analysis using individual patient data in order to identify subgroups with specific types of multimorbidity (e.g., particular combinations of conditions, patients with poor general health, etc.). Where patients with comorbidities are excluded from studies, more attention should be given to the serious limitation that this places on the generalizability of the research findings (Box 11.3).

Box 11.3 Recommendations for research

- Do not exclude patients with comorbidities from research studies

- In studies of interventions, include in the analysis plan a comparison of effectiveness in patients with or without comorbidities

- Undertake meta-analyses using individual patient data from existing trials in order to explore the impact of interventions for subgroups of patients with different types of multimorbidity

- Develop better measures of continuity and coordination of care in order to be able to assess the benefits of different approaches to delivering care

- Test organizational interventions that are designed to promote continuity and coordination of care for people with multimorbidity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree