Iliopubic Tract Repair of Inguinal Hernia: the Anterior (Inguinal Canal) Approach

Robert E. Condon

The fundamental defect in the structure of the anterior abdominal wall that allows the development of direct and indirect inguinal hernias lies in the deep—or transversus abdominis—musculoaponeurotic layer of the groin. Anatomic reconstruction of these hernias, therefore, involves closure of tissues within the transversus abdominis layer. Closure of the transversus abdominal layer is the only way of anatomically repairing the internal ring. The method of hernial repair described in this chapter—in which the hernia is repaired by the traditional anterior approach through the inguinal canal and the iliopubic tract is used as the anchor for the repair—evolved from an appreciation of groin anatomy gained by dissections in the anatomy laboratory, autopsy room, and operating room. In developing this method, I have emphasized the importance of reconstruction of relatively normal anatomy insofar as the individual situation allows. A thorough understanding of groin anatomy is absolutely essential to success in hernial repair.

The elements of successful construction of a sound primary repair of an inguinal hernia are as follows:

Know the anatomy, especially the structure of the transversus abdominis layer.

Remember that the anatomic relationships in the groin are relatively constant, although variation is the norm.

Identify the hernial defect intraoperatively by sharp dissection.

Excise the weak and redundant tissues overlying and surrounding the hernia.

Clear the borders of the hernial defect to strong tissue.

Test the tissue borders to ensure that they will retain sutures.

Close the defect by suture, avoiding tension by means of a relaxing incision when needed.

Insert a prosthesis whenever loss of tissue or the size of the hernia indicates that primary repair may not succeed.

In this chapter, techniques are described for the repair of typical indirect and direct inguinal hernias. Repair of a complete hernia—the variety of large indirect inguinal hernia that has destroyed the posterior wall of the inguinal canal—combines features of both indirect and direct repairs and is also discussed.

The anterior iliopubic tract repair is suitable for all varieties of indirect and direct inguinal hernias in adults. To avoid incision through the posterior inguinal wall, an area itself subject to herniation, femoral hernias should not be approached anteriorly; the posterior approach is preferred.

This method should not be used for repair of the small indirect inguinal hernia usually found in infants; such hernias do not greatly enlarge the deep inguinal ring and require only excision of the sac and, in some instances, one or two stitches to close the deep ring. Recurrence after previous repair of an indirect inguinal hernia typically occurs at the lateral aspect of the deep inguinal ring and can be repaired through an anterior approach; however, I prefer the posterior, or preperitoneal, approach through fresh tissue for repair of recurrent direct hernias under most circumstances. I also prefer a posterior approach for repair of suspected sliding hernias.

Preparation, Incision, and Exposure of the Hernia

Shave only the area around the proposed incision that will be covered by the dressing and adhesive tape postoperatively. It is not necessary to shave the entire perineum. Shaving should be done in the operating room immediately before skin preparation. Scrub the lower abdomen, perineum, scrotum, and upper thighs with an iodophor solution or chlorhexidine solution. Do not use alcohol-based solutions for skin preparation because they can cause painful scrotitis. In draping, place a sterile towel under the scrotum and a second one over it to permit aseptic access to the scrotum as needed intraoperatively.

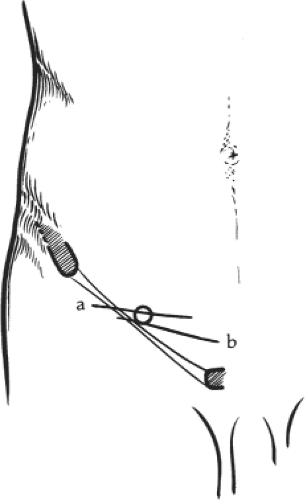

The deep inguinal ring, through which an indirect inguinal hernia obtrudes, is situated halfway between the pubic tubercle and the anterior superior iliac spine. The incision for repair of an indirect inguinal hernia is centered directly over the projected location of the deep inguinal ring and is made more or less transversely, following a natural skin crease or tension line (Fig. 1). In large or complete indirect inguinal hernias that involve the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, the incision is extended medially to provide additional access. In a direct inguinal hernia, the defect is situated between the deep inguinal ring and the pubic tubercle. The upper border of the hernial defect should be identified by palpation, and the incision should be placed just below the level of the superior margin of the direct inguinal hernial defect, centered on the hernial bulge, and made transversely, following a skin crease (Fig. 1). Incisions for repair of a direct hernia are located somewhat more medial and inferior to those used for repair of an indirect inguinal hernia.

The skin and most of the subcutaneous fat are incised in one sweep to expose the external oblique aponeurosis with its overlying

investing (innominate) fascia. Branches of the superficial epigastric vessels are encountered in the medial half of the incision and of the superficial circumflex iliac vessels in the lateral half. The Scarpa fascia can sometimes be identified within the subcutaneous fat as an opaque layer; it does not need to be sutured during wound closure.

investing (innominate) fascia. Branches of the superficial epigastric vessels are encountered in the medial half of the incision and of the superficial circumflex iliac vessels in the lateral half. The Scarpa fascia can sometimes be identified within the subcutaneous fat as an opaque layer; it does not need to be sutured during wound closure.

The skin and subcutaneous fat are retracted sufficiently to expose the upper portion of the superficial inguinal ring. It is not necessary to clean the external surface of the external oblique aponeurosis thoroughly. A small incision, approximately 1 cm long, is made with the knife between fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis in the middle portion of the main incision, placed so that, if extended, it carries into the apex of the superficial inguinal ring. The lower border of the external oblique incision is picked up with a Cushing forceps, and the closed points of a pair of Metzenbaum scissors are inserted and gently passed laterally on the deep aspect of the external oblique aponeurosis, separating the underlying internal oblique musculature and the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves from the external oblique aponeurosis.

One blade of the scissors is now inserted deep into the aponeurosis and the other blade is maintained superficial to it; the scissors, in a slightly open position, are pushed laterally between contiguous fibers of the external oblique aponeurosis to open the lateral aspect of this layer. Fine hemostats are applied to the edges of the incision in the external oblique aponeurosis to provide traction. The closed scissors tip is now directed medially beneath the external oblique aponeurosis, separating the underlying nerves and musculature, and the aponeurosis is split in a similar manner down to the superficial inguinal ring.

If dealing with an indirect inguinal hernia that has passed through the superficial ring into the scrotum, it may be necessary to open the superficial ring; certainly, it is not necessary to do so on a routine basis. A self-retaining retractor is placed deep into the external oblique lamina at either end of the incision to maintain exposure of the deeper tissues. Care needs to be taken throughout this portion of the dissection to protect both the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. Usually the ilioinguinal nerve has to be picked up gently and dissected free from the internal oblique muscle so that the nerve can be carried superiorly or inferiorly out of the surgical field and held behind a hemostat placed on the edge of the external oblique aponeurosis.

The lower leaf of the external oblique aponeurosis is grasped in its middle portion and retracted inferiorly. The spermatic cord is grasped gently and retracted anteriorly and superiorly. The areolar attachments of the cremasteric fascia to the deep surface of the external oblique aponeurosis and the inguinal ligament are separated bluntly, the dissection continuing posteriorly until the deepest aspect (shelving border) of the inguinal ligament has been exposed from the pubic tubercle through the insertion of the cremaster muscle.

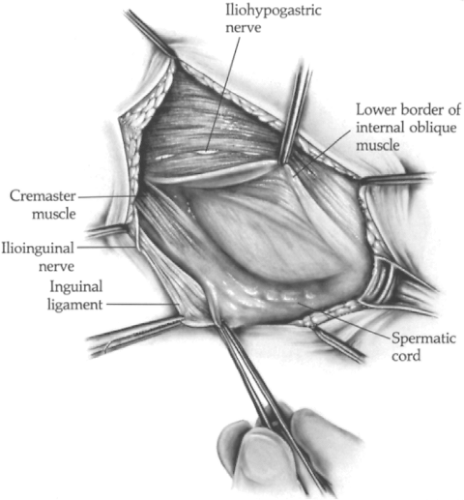

The spermatic cord is then gently retracted inferiorly. The lower border of the internal oblique muscle is found by identifying those muscle bundles that attach to the rectus sheath. The bundles of the cremaster muscle are identified by following them from their lateral attachment and noting that they continue with the spermatic cord. The lower border of the internal oblique muscle is retracted superiorly, the spermatic cord is retracted inferiorly, and the dissection is continued in the plane between the internal oblique and cremaster muscles on the superior and then the posterior aspect of the cord (Fig. 2), separating the cord from the posterior inguinal wall over the entire distance between the pubic tubercle and the medial border of the deep inguinal ring.

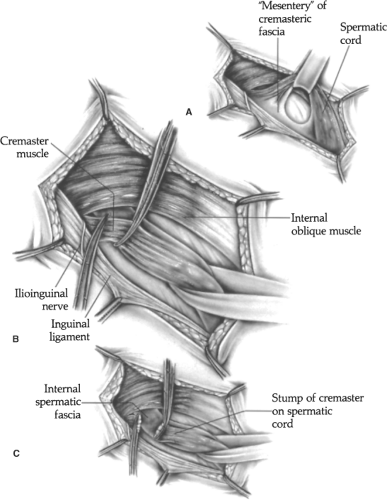

As mobilization of the spermatic cord proceeds, a small mesentery of cremasteric fascia on the deep aspect of the cord is developed. When the cord is sufficiently mobilized, the mesentery is transected or broken through bluntly, thrusting a finger from above to below and carefully avoiding the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. The cord is encircled with a small Penrose drain (Fig. 3A). The dissection is continued on the undersurface of the cord, progressing medially to the pubic tubercle and laterally beneath the deep inguinal ring to the origin of the cremaster muscle.

An indirect inguinal hernia can now be visualized as a bulging sac contained within the cremasteric fascia and the internal spermatic fascia and emerging through the deep inguinal ring on the superior aspect of the cord. A direct inguinal hernia presents as a diffuse bulge or redundancy of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. A few fibers of transversus abdominis aponeurosis may

be spread widely over the surface of a direct hernia, but for the most part, the hernial sac is composed of stretched transversalis fascia and peritoneum.

be spread widely over the surface of a direct hernia, but for the most part, the hernial sac is composed of stretched transversalis fascia and peritoneum.

The transversalis fascia is often opaque and may appear thick and strong; the appearance, however, is illusory. Transversus aponeurosis, rather than transversalis fascia, must be identified and used for the repair. A complete inguinal hernia, the variety that begins as an indirect hernia but progressively enlarges medially to break down the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, has features of both indirect and direct hernias. At some point the displaced inferior epigastric vessels restrict the protrusion of peritoneum in a complete inguinal hernia, so that some “pantaloon effect” is usually present.

Repair of an Indirect Inguinal Hernia

In a typical indirect inguinal hernia, the sac is confined within the structures of the spermatic cord, and the posterior inguinal wall remains intact. It is essential that the entire circumference of the deep inguinal ring be exposed by dissection in the course of the hernial repair. This can be accomplished only by mobilization of the cremaster muscle to expose the lateral side of the deep inguinal ring, usually by transecting the cremaster muscle at its origin (Fig. 3B), although retracting the muscle is sufficient in some instances to provide the needed exposure.

At the lateral aspect of the deep inguinal ring, the tip of a hemostat is inserted bluntly from above downward, beneath the cremaster muscle but superficial to the iliopubic tract and the inguinal ligament. The ilioinguinal nerve is identified once again to be sure that it has been retracted and is protected. The cremaster muscle is mobilized and retracted to expose the lateral and inferior margins of the deep inguinal ring. Sometimes, to gain adequate exposure, it is necessary to transect the cremaster muscle. Paired hemostats are applied across the origin of the cremaster muscle, and the muscle is cut between the clamps (Fig. 3C). The proximal stump of cremaster muscle is suture-ligated to control the cremasteric artery; a simple ligature is sufficient to manage the distal stump.

Any remaining fascicular or areolar attachments of cremasteric fascia at the deep inguinal ring are transected about the entire circumference of the spermatic cord. Distal traction on the cord now makes the internal spermatic fascia (continuous with the transversalis fascia) stand out. The internal spermatic fascia is transected circumferentially around the hernial sac and cord approximately 1 cm distal to the deep inguinal ring. As this dissection proceeds at the inferior aspect of the deep inguinal ring, a small arterial branch, the external spermatic artery, may be noted perforating the transversalis fascia or the adjacent iliopubic tract to join the spermatic cord; this vessel can be preserved or transected and ligated.

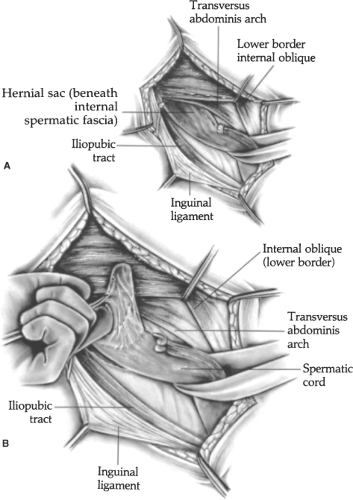

The peritoneal hernial sac, the margins of the deep inguinal ring, the iliopubic tract, and the transversus abdominis arch should now be identified. The iliopubic tract is present immediately adjacent to the inguinal ligament at the inferior aspect of the deep inguinal ring. The transversus abdominis arch can be palpated at the superior aspect of the deep inguinal ring after retracting the overlying lip of internal oblique muscle.

In most instances, the peritoneal sac protrudes through the superior aspect of the deep inguinal ring and is found along the anterior aspect of the cord. In unusual instances, the sac protrudes at the medial aspect of the deep ring between the spermatic cord and the inferior epigastric vessels. In recurrent hernias, the sac usually protrudes at the lateral aspect of the ring. Tendency to recurrence at the lateral aspect of the ring is dictated by the fact that this aspect of the ring usually has not been sutured by the surgeon performing the previous hernial repair.

The tissues covering the hernial sac within the cord—the cremasteric and internal spermatic fasciae—should be cleared from the sac by sharp dissection sufficiently to allow the surgeon to grasp the peritoneal sac directly. A small incision is made into the sac, 2 cm distal to the deep inguinal ring (Fig. 4A). The forefinger is inserted and directed distally through the incision. A fine hemostat is applied to the distal apex of the sac incision and held on traction in the palm of the operator’s hand to facilitate subsequent dissection.

The sac is removed from the spermatic cord by upward and proximal traction maintained by flexing the forefinger within the sac while the cremasteric and internal spermatic fascia are cleared away, chiefly by sharp dissection (Fig. 4B). Sharp dissection is emphasized because blunt dissection increases the risk of injury to the blood vessels of the spermatic cord, which are spread out on the surface of the hernial sac. Clearing of the fascia from the hernial sac is facilitated by maintaining traction on the margins of the cremasteric and internal spermatic fasciae as the dissection proceeds. The dissection is made in the plane between the sac and fasciae, initially clearing the superior and anterior two-thirds of the circumference of the sac. As the initial segment is cleared, the incision in the sac is extended distally, the hemostat is replaced at the apex of the incision, the finger is thrust farther distally, and the dissection is continued until the apex of the sac is reached and mobilized. When the most distal end of the peritoneal sac is reached, the tip of the finger within the sac is flexed anteriorly, and dissection on the posterior aspect of the sac is continued back to the level of the deep inguinal ring.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree