Ileoanal Pouch Procedure for Ulcerative Colitis and Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Feza H. Remzi

Victor W. Fazio

Restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis has been viewed as the most recent development in the evolution of continence-preserving procedures and has become the “gold standard” surgical treatment for the majority of patients with ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. It establishes gastrointestinal system continuity and anal continence, and avoids permanent stomas. Like so many surgical techniques, restorative proctocolectomy is not new in concept, and the origin of straight ileoanal anastomosis dates back to the 1940s. Functional outcome of this procedure was poor and was associated with a high frequency of defecation and urgency. Surgical techniques, however, continued to evolve, and to address these problems, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis was described first in experimental animals as early as 1955 by Valiente and Bacon. Finally in 1978, Sir Allen Parks from St. Marks Hospital in London reported the first application of S-shaped ileoanal pouch anastomosis in humans. At the same time, Fonkalsrud and Martin pioneered their method of ileoanal pouch formation, again based on the three-looped reservoir. These led to the improvement of functional results related to frequency, urgency, continence, and less morbidity than the straight anastomosis. This technique began a new era in surgical management of ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Many refinements of the ileoanal pouch procedure have occurred since the original description of total proctocolectomy, anorectal mucosectomy, hand-sewn ileal pouch–anal anastomosis, and diverting ileostomy. Some of these refinements include the introduction of different types of pouches and stapled anastomosis. However, the principles of the ileoanal pouch procedure have not changed and involve a conventional total proctocolectomy, construction of an ileal pouch, and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. In most cases, a temporary diverting loop ileostomy is also constructed.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is the principal indication for restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Many patients with ulcerative colitis who are refractory to medical therapy and steroid dependent are suitable for this procedure. This constitutes the primary indication for the ileoanal pouch procedure in our institution.

Indeterminate Colitis

The dilemma and clinical difficulties of a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis relate to the concern surgeons express about performing pouch

surgery in a patient whose final diagnosis is Crohn disease. Pouch failure rates are increased in patients with Crohn disease. A diagnosis of indeterminate colitis implies a significant chance that the ultimate diagnosis can be Crohn disease. This then mandates great circumspection by the surgeon when advising the patient about pouch alternatives for indeterminate colitis. In most cases, careful examination of gross and microscopic features will allow categorization of inflammatory bowel diseases as either mucosal ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. About 10% of the cases will cause significant differential diagnostic problems by illustrating ambiguous features. Almost always, these cases are fulminant or toxic clinical disease requiring urgent or emergent colectomy in which pathologic features are ambiguous and do not permit precise separation of Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis. The histologic diagnosis of indeterminate colitis essentially indicates that the pathologist is unable to identify histologic features strongly in favor of either ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. We believe it is safe to construct an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in the patients with indeterminate colitis. In our experience, functional results and the incidence of anastomotic complications and major pouch fistulae have been the same in ulcerative and indeterminate colitis patients. Although indeterminate colitis patients were more likely to develop minor perineal fistulae, pelvic abscess, and Crohn disease, the rate of pouch failure was identical to that of ulcerative colitis patients. There was also no clinically significant difference in quality of life or satisfaction with ileal pouch surgery.

surgery in a patient whose final diagnosis is Crohn disease. Pouch failure rates are increased in patients with Crohn disease. A diagnosis of indeterminate colitis implies a significant chance that the ultimate diagnosis can be Crohn disease. This then mandates great circumspection by the surgeon when advising the patient about pouch alternatives for indeterminate colitis. In most cases, careful examination of gross and microscopic features will allow categorization of inflammatory bowel diseases as either mucosal ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. About 10% of the cases will cause significant differential diagnostic problems by illustrating ambiguous features. Almost always, these cases are fulminant or toxic clinical disease requiring urgent or emergent colectomy in which pathologic features are ambiguous and do not permit precise separation of Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis. The histologic diagnosis of indeterminate colitis essentially indicates that the pathologist is unable to identify histologic features strongly in favor of either ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease. We believe it is safe to construct an ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in the patients with indeterminate colitis. In our experience, functional results and the incidence of anastomotic complications and major pouch fistulae have been the same in ulcerative and indeterminate colitis patients. Although indeterminate colitis patients were more likely to develop minor perineal fistulae, pelvic abscess, and Crohn disease, the rate of pouch failure was identical to that of ulcerative colitis patients. There was also no clinically significant difference in quality of life or satisfaction with ileal pouch surgery.

Late pouch complications are more common in the presence of preoperative clinical features suggestive of Crohn disease, such as perianal disease. The presence of perianal or small bowel disease indicates that the disease is likely to behave more like Crohn disease than ulcerative colitis. Though functional outcome, quality of life, and pouch survival rates are equivalent after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for indeterminate and ulcerative colitis, there is an increase in some complications and in the late diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn Disease

In contrast, a proved diagnosis of Crohn disease is generally held to preclude ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. However, the patients with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for apparent mucosal ulcerative colitis, who are subsequently found to have Crohn disease, have a variable course. In our experience, the patients who underwent ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for mucosal ulcerative colitis and who subsequently had that diagnosis revised to Crohn disease had favorable outcome. No pre-ileal pouch–anal anastomosis factors examined were predictors of the development of recrudescent Crohn disease. The overall pouch loss rate for the entire cohort was 12%, and was 33% for those with recrudescent Crohn disease during 46 months of follow-up. The secondary diagnosis of Crohn disease after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis was associated with protracted freedom from clinically evident Crohn disease, low pouch loss rate, and good functional outcome. We believe such results can only be improved by the continued development of medical strategies for the long-term suppression of Crohn disease, and our data support a prospective evaluation of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in selected patients with Crohn disease.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

Restorative proctocolectomy is the preferred operation in older patients, especially those older than 30 years, because the risk for cancer rises with age. Restorative proctocolectomy removes all large bowel and mucosa, and theoretically eradicates the risk for colorectal cancer. The risk for polyps and cancer in the small bowel remains unchanged. There is controversy about the functional outcome comparing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis with total proctocolectomy and colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. The previous studies showed that there was no functional outcome difference between these groups. Recently, several reports have challenged this notion, favoring the ileorectal anastomosis. At the same time, the risk of carcinoma developing in the rectal stump after an ileorectal anastomosis can be as high as 32% 20 years after anastomosis. However, this concern should be reconsidered in the postpouch era because prior to the ileoanal pouch procedure, generally all patients were recommended for ileorectal anastomosis unless they had associated carcinoma. In our recent review, the risk of carcinoma developing in the rectal stump in the postpouch era was minimal.

Restorative proctocolectomy is a more complex surgical procedure than colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis and is associated with a higher morbidity. For this reason, in affected young adolescents, when the risk of cancer is low, colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis is a valuable option because of its simplicity, good function, and absence of the need for a temporary stoma. We see the ileoanal pouch procedure as most suitable in young patients who present with diffuse multiple polyps in the rectum (>20 in proctoscopy) or in the patient with a late-onset disease and a malignancy in the upper rectum or colon. It is also an option in the patients who have previously had an ileorectal anastomosis and who have an unmanageable number of polyps in the rectum. Patients may choose restorative proctocolectomy because the cancer risk is lower than with ileorectal anastomosis. At the same time, the patient’s wishes, extent of rectal involvement, availability of follow-up, and morbidity rate of restorative proctocolectomy should be considered before proceeding with this procedure.

In the patients who have polyposis with an established colonic malignancy, or diffuse polyposis in rectum, the risk of further carcinoma developing is increased. Thus, unless the cancer is advanced or the distribution of polyps in the rectum is sparse, restorative proctocolectomy and ileoanal pouch–anal anastomosis is the surgical procedure of choice in the patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.

Miscellaneous

Multiple polyps, multiple cancers of the colon and rectum, and functional bowel disease may also be indications for restorative proctocolectomy. The indication for functional bowel disease is controversial. The results are variable. It is reserved for the patients in whom more conventional procedures have failed and when the patient refuses to have an ileostomy. In these circumstances, the procedure should be performed after extensive discussion with the patient, indicating limitations of the procedure. Motility disorder that causes a slow colonic transit may similarly affect the small bowel. Psychological assessment of the patient is important.

Contraindications

Documented Crohn disease, advanced low-lying rectal cancer, and inadequate anal sphincter function are contraindications to pouch construction. There are no absolute contraindications to restorative proctocolectomy on the grounds of age at either extreme. However, resting and squeeze anal pressures tend to fall with age, especially in women older than 60 years of age. Serious co-morbid factors are also more common in the elderly.

Timing of Surgery

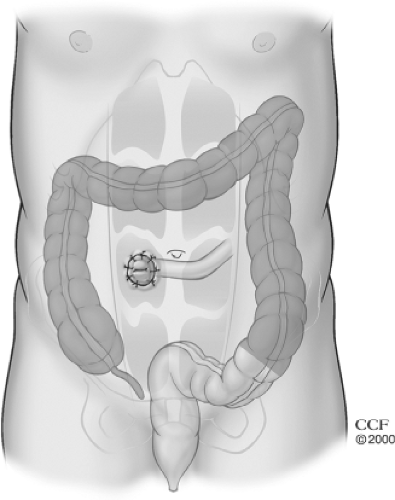

Restorative proctocolectomy is an elective operation. In the patients with a diagnostic

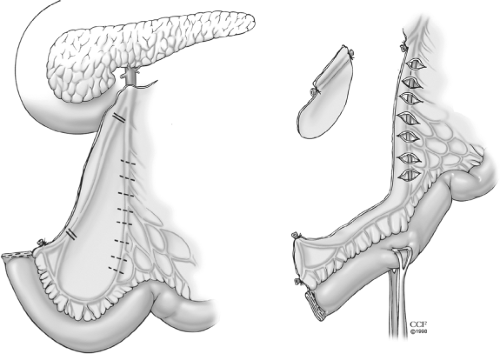

dilemma of Crohn disease, requirement for high-dose prednisone (50 to 60 mg/d), signs and symptoms of toxicity, gross obesity, or malnutrition, staging the restorative proctocolectomy with initial subtotal or total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy is our preferred approach (Fig. 1). We prefer suturing the stapled rectosigmoid stump to the distal aspect of the incision (Fig. 2). This places the suture line extraperitoneally, and if breakdown at the staple line occurs, drainage from the rectal stump can be controlled via a lower incisional fistula without the patient becoming septic. This technique also provides an easier identification of the rectal stump at the time of the second stage of the procedure when the ileal pouch is constructed.

dilemma of Crohn disease, requirement for high-dose prednisone (50 to 60 mg/d), signs and symptoms of toxicity, gross obesity, or malnutrition, staging the restorative proctocolectomy with initial subtotal or total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy is our preferred approach (Fig. 1). We prefer suturing the stapled rectosigmoid stump to the distal aspect of the incision (Fig. 2). This places the suture line extraperitoneally, and if breakdown at the staple line occurs, drainage from the rectal stump can be controlled via a lower incisional fistula without the patient becoming septic. This technique also provides an easier identification of the rectal stump at the time of the second stage of the procedure when the ileal pouch is constructed.

This staged operation may be associated with a higher operative morbidity such as sepsis and small bowel obstruction than a colectomy and ileoanal anastomosis at a single operative setting. However, in the aforementioned patient population, preliminary abdominal colectomy and end ileostomy with delayed ileal pouch construction are prudent. For these patients, ileal pouch–anal anastomosis is deferred 6 months because the adhesions can be extensive before that time. In over 90% of our cases, a temporary diverting loop ileostomy is constructed. This is closed 3 months later. Closure before that time is technically more difficult because of dense peri-ileostomy adhesions. We do routinely obtain a Gastrografin enema and pouch endoscopy prior to ileostomy closure to check for pouch and anastomotic integrity. If a laparotomy for adhesive bowel obstruction is necessary at any time, the ileostomy may be closed during the same procedure as long as the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis is intact and has the patency confirmed with Gastrografin enema and pouch endoscopy.

There are few operations where discussion with the patient and his or her family is so extensive. A complete and factual discussion of the indications for surgery, alternative treatments, sequelae, complications, and anticipated or possible outcomes is held. Preoperative preparation includes a preoperative assessment of the patient’s fitness for surgery and assessment of the extent of colonic disease and anal sphincter function. A full colonoscopy with biopsies to determine Crohn disease or dysplasia is important. This is especially true where we commonly do serial biopsies from the lower and midrectum in the patients with long-standing disease or known colonic dysplasia as this may impact the type of anastomosis that will be used. An introduction to life with stoma by an enterostomal therapist is beneficial. A site for the temporary ileostomy is also marked preoperatively. Mechanical bowel preparation is provided by using polyethylene glycol or Fleet Phospho Soda.

Fig. 2. The rectosigmoid stump is sutured to the lower aspect of incision extraperitoneally beneath the skin and subcutaneous tissue but above the fascia. |

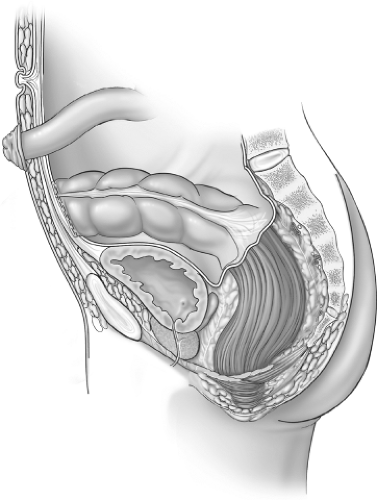

At the time of the surgery, the patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position with the legs supported by Lloyd Davies Stirrups. Rectal washout with normal saline is performed in the operating room until the fluid

return is clear. A urethral Foley catheter and a nasogastric tube are inserted after induction of anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotics, usually metronidazole and a third-generation cephalosporin, are given at induction and continued postoperatively for 2 to 5 days depending upon the degree of intraoperative contamination. Prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis is also instituted.

return is clear. A urethral Foley catheter and a nasogastric tube are inserted after induction of anesthesia. Intravenous antibiotics, usually metronidazole and a third-generation cephalosporin, are given at induction and continued postoperatively for 2 to 5 days depending upon the degree of intraoperative contamination. Prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis is also instituted.

The principles of restorative proctocolectomy and ileoanal pouch procedure involve a conventional total abdominal colectomy, proctectomy, construction of an ileal pouch, and ileoanal anastomosis.

Abdominal Dissection

A midline incision is made and a thorough laparotomy is performed to note whether there is any evidence of small bowel Crohn disease or any unsuspected neoplasm. The abdominal colectomy is performed in the standard manner with mesenteric vessels ligated and divided close to the bowel. However, in the patients with a preoperative diagnosis of low- or high-grade dysplasia or cancer, or where the patient has long-standing disease of 10 or more years, we recommend a high ligation of the mesenteric vessels with a radical colectomy.

Proctectomy

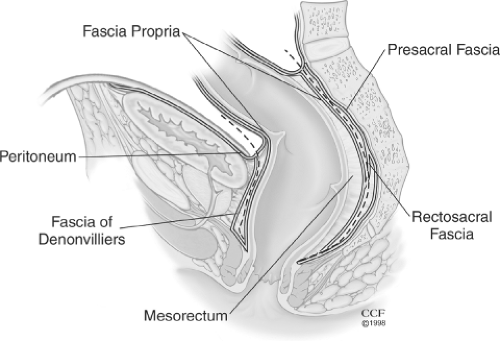

Proctectomy should be done by avoiding any injury to the ureters and nervi erigentes. This can be accomplished by staying within the correct fascial planes. After identifying the ureters, the rectum is mobilized by first entering the presacral fascia between the investing layer of fascia propria of the mesorectum and presacral fascia (Fig. 3, dotted line). The presacral nerves are identified at the pelvic rim and preserved. The posterior pelvic dissection is continued midline posteriorly between the investing layer of the rectum and Waldeyer fascia to the level of the levator floor. It is important not to breech presacral fascia where nervi erigentes and presacral veins are vulnerable. Breaching this fascia may cause significant bleeding. Most of this dissection is usually done with cautery, is practically bloodless, and is expeditious, and the risk of impotence is low. After the posterior dissection is complete, anterior dissection is done starting about 1 cm above the peritoneal reflection (Fig. 3, dotted line). The plane of dissection is posterior to the Denonvilliers fascia and the seminal vesicles should not be seen. Beyond this level, a close rectal dissection is performed. This will ensure minimizing the risk of damaging the autonomic plexus that lies anterior to the Denonvilliers fascia. Lighted retractors allow good visualization of the pelvic structures. Throughout the pelvic dissection, firm traction on the rectum is essential. This is facilitated by placing the tissues under tension by using traction and countertraction. The lateral ligaments are divided close to the rectum with cautery. Occasionally, middle rectal vessels within the lateral ligaments may require suture or clip ligation. Anterior dissection close to the rectal wall is carried to the lower one-third of the vagina, or to the lower border of the prostate gland. At this stage the rectum is fully mobilized down to the levators and an occluding tape is applied to the midrectum to avoid spillage. The next step, the transaction of the rectum, will depend on the plans for the type of the anastomosis, namely, stapled anastomosis or anorectal mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis. After the transection, a pack is placed deep in the pelvis, abutting the levators to maximize the hemostasis; also, the specimen is opened and examined to rule out Crohn disease or associated colorectal cancer.

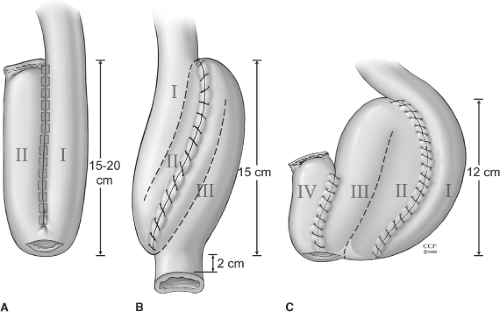

Pouch Design

The goal in restorative proctocolectomy and ileoanal pouch procedure is to construct a compliant sac of two or more loops of terminal ileum. Pouch construction has been shown to be superior to straight ileal anal anastomosis in terms of function. Several pouch designs using sutured or stapled techniques have been described. The foremost common pouch designs are the two-loop J-pouch, the triple-loop S-pouch, and the four-loop W-pouch with use of either sutured or stapled techniques. The functional results of these various pouch designs (Fig. 4) appear to be comparable where the J-pouch is easiest to construct and has functional outcomes identical to those of more complex designs. Factors other than pouch design, such as bacterial overgrowth, gut motility, and transit, probably play a more important role in deciding the functional outcome. There does not appear to be any correlation between ileal pouch capacity at the time of construction and functional outcome. However, the size of the pouch is of some importance. A very small pouch cannot fulfill its role as a reservoir, and a large floppy pouch may be associated with ineffective evacuation. In general, pouch capacity increases by two to four times at 1 year after construction.

The J-pouch is the pouch design of choice at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. However, the S-pouch usually reaches 2 to 4 cm farther than does the J-pouch and is useful in the patients with a short, fat mesentery and long, narrow pelvis when the reach of the ileal pouch to the anal canal can be a problem. In our practice, this is especially true in the patients where mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis is indicated due to neoplasia.

Small Bowel Mobilization and Reach

The key to the construction of an ileoanal pouch anastomosis is to mobilize the small bowel adequately so that it will reach to the levator floor without tension. This can

especially be a problem for obese patients, patients with extensive adhesions from previous surgery (such as in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP] and desmoids), patients with previous small resection, or patients necessitating mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis. In order to accomplish this, the small bowel mesentery is totally mobilized as far as the third part of the duodenum and inferior border of the pancreas. In our practice, we ligate and excise the ileocolic artery and vein at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. This provides a better mobility and tension-free anastomosis.

especially be a problem for obese patients, patients with extensive adhesions from previous surgery (such as in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [FAP] and desmoids), patients with previous small resection, or patients necessitating mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis. In order to accomplish this, the small bowel mesentery is totally mobilized as far as the third part of the duodenum and inferior border of the pancreas. In our practice, we ligate and excise the ileocolic artery and vein at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. This provides a better mobility and tension-free anastomosis.

The segment of ileum requiring the greatest mobility varies with pouch design. For this reason, before transection of the rectum, we make sure the pouch reaches to the distal aspect of the anal canal either for planned stapled anastomosis or for mucosectomy with hand-sewn anastomosis. The junction of the two loops of small bowel and the end-terminal ileum are the two points that require greatest mobility for the J-pouch (two loop) and S-pouch (three loop). The apex of the J-pouch is about 15 cm from the end of the ileum. That of the S-pouch is at the bowel end itself. The reach can be estimated by placing a Babcock clamp at the apex of the ileal pouch and grasping that and simulating the reach down to the levator floor. The reach is estimated by delivering the clamped apex into the pelvis and having the clamp abut the top of the levator floor or the index finger that is inserted into the anus (Fig. 5). The S-pouch usually reaches 2 to 4 cm farther than the J-pouch and can be helpful if there is likely to be tension with the anastomosis.

If these maneuvers fail to give clear indications that reach is tension free, which is especially true in obese patients or in patients who have had a previous small bowel resection, a number of maneuvers can be helpful. If further mobilization is necessary, excision of all peritoneal tissue to the right of the superior mesenteric vessels, leaving a very small edge of peritoneum lateral to these vessels, may provide added mobility (Fig. 6). Preservation of superior mesenteric vessels and their terminal arcades is important. Use of translumination facilitates identification of vessels that must be preserved. A further maneuver that is helpful is the making of a series of transverse 1- to 2-cm peritoneal incisions over the superior mesenteric vessels anteriorly and posteriorly (Fig. 6). Formal mobilization of the duodenum with Kocher maneuver may also give additional mobility to provide a tension-free anastomosis. These maneuvers usually add at least 2 to 3 cm to mobility.

Ileal Pouch Construction and Ileal Pouch–Anal Anastomosis

When an ileoanal pouch is performed, controversy exists about the technique to be used for the pouch–anal anastomosis. Techniques of anastomosis vary between a hand-sewn ileal pouch–anal anastomosis with mucosectomy of the anal transitional zone and a stapled ileal pouch–anal anastomosis at the level of the anorectal ring without mucosectomy of the anal transitional zone. Therefore, the optimal level of anorectal transsection is controversial after the rectal dissection. This controversy centers on the potential advantages and disadvantages of leaving a mucosal cuff of anal transitional zone ranging from 1 to 2 cm in length in order to allow transanal insertion of the stapler head. By transecting the rectum at the top of the anal columns (anorectal ring), as

in stapled anastomosis, the anal sensory epithelium is preserved and tension on the pending ileoanal anastomosis is also minimized. Therefore, the potential advantages of stapled anastomosis include better functional results, lower rate of septic complications, and ease of construction; disadvantages include possible malignant or premalignant transformation of the columnar epithelial cells in the retained mucosal cuff and a longer, more difficult surgery.

in stapled anastomosis, the anal sensory epithelium is preserved and tension on the pending ileoanal anastomosis is also minimized. Therefore, the potential advantages of stapled anastomosis include better functional results, lower rate of septic complications, and ease of construction; disadvantages include possible malignant or premalignant transformation of the columnar epithelial cells in the retained mucosal cuff and a longer, more difficult surgery.

The prospective randomized trials have not shown a difference in functional outcome and septic complications between the two methods. However, these studies warrant careful analysis because of the relatively short-term follow-up, and the small number of cases studied makes them vulnerable to type II error. Our initial studies comparing the two types of techniques showed less septic complications and better functional outcome favoring stapled anastomosis. The most recent review from our institution of over 2,000 patients continued to show superior functional results in patients with stapled anastomosis where the septic complications showed some increased trend in mucosectomy group, but this did not reach the statistical difference like the prior studies from our institution.

The estimated incidence of anal transitional zone dysplasia in our most recent study was 4.5% without any occurrence of invasive cancer in patients with a minimum of 10 years of surveillance. However, the risk of anal transitional dysplasia was significantly associated with cancer or dysplasia as a preoperative diagnosis or in the proctocolectomy specimen. More recently we had two cases of anal transitional zone cancer where both were successfully treated. Mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis may decrease this concern but cannot fully eliminate the neoplasia risk because islands of colonic-type mucosa can be present even at the level of the dentate line or potential remnant columnar cells and left at the time of the mucosectomy dissection. These areas are later covered with the pouch itself where further surveillance of the mucosectomized anal transitional zone could not be as discrete as in stapled anastomosis. A very distal anal canal transsection may also lead to excision of some internal anal sphincter. In our practice, we favor mucosectomy with hand-sewn anastomosis in the patients with a known diagnosis of rectal cancer or dysplasia in the lower two-thirds of rectum before the surgery.

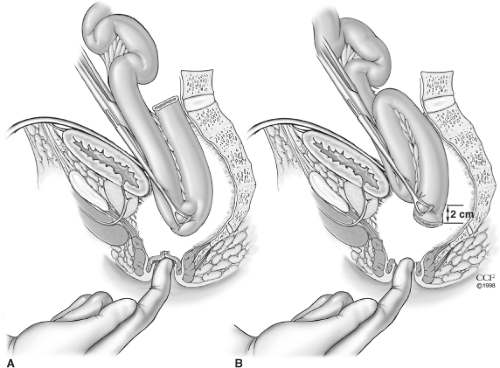

A stapled ileal pouch–anal anastomosis may be constructed using either a double-stapling technique or a single-stapling technique. Double-stapled ileoanal pouch anastomosis is our preferred technique at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. If a stapled anastomosis is intended, the surgeon marks the level of planned anastomosis by transanal digital examination. With the proximal interphalangeal joint resting at the anal verge, the tip of the digit corresponds to the anorectal ring (Fig. 7). At this point the level is marked by the use of cautery on the anterior surface of the rectum, and this corresponds to the level of linear staple for double-stapling anastomosis or purse-string suture for single-stapling anastomosis.

The double-stapling technique obviates the frustration of inserting purse-string sutures in the anorectum deep in the pelvis and minimizes intraoperative contamination. Disparity of the size of the bowel lumen is also avoided. With this technique, the distal anorectal stump is closed with a linear stapler. The PI 30 instrument (U.S. Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT) has a restraining pin to prevent extrusion of the tissues during staple closure. The linear staple line on the anorectum should rest at a level just below the superior border of the levator floor. In the patients with a wide pelvis, there is a potential hazard that the linear stapler may be applied too distally, which could lead to the excision of a significant amount of internal sphincter when subsequent ileal pouch–anal anastomosis is performed. Thus, the level of the intended ileoanal anastomosis should be determined and marked beforehand, as emphasized in Figure 7. Because of oblique positioning of the linear stapler on the anorectum, the posterior anastomotic line tends to be more distal than that of the anterior anastomotic line. After the stapler is fired, the specimen is divided above the linear staple line by using a long-handled knife (Fig. 8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree