![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the student pharmacist, community practice resident, or pharmacist should be able to:

1. Accurately measure blood pressure (BP).

2. Appropriately classify severity of hypertension (HTN) by using the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) staging classification.

3. Identify compelling indications to assist with selection of appropriate pharmacotherapeutic agents for treatment of HTN.

4. Educate patients of the impact of lifestyle changes on BP control.

5. Develop pharmacotherapy treatment plans for patients with HTN, including those with compelling indications, difficult to treat HTN, and special populations.

6. Identify potential barriers to implementing services for patients with HTN in a community pharmacy.

7. Design workflow in a community pharmacy to establish and maintain services for patients with HTN.

BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION

Epidemiology of Hypertension in the United States

The 2011 Update on Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics indicates that 29% of adults (≥18 years) in the United States have high BP.1 According to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 30.4% (66.9 million) of US adults (≥18 years) have HTN, defined as average BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, or currently using blood pressure lowering medication.2

HTN prevalence varies with age, sex, race, and ethnicity.1,3 The prevalence of high BP is greater in men in the age group of 18–44 years. Women and men have equal prevalence from the age of 45–64 years. Women have a higher prevalence of high BP starting at age 65. Prevalence of HTN is greatest among black Americans. Black Americans have a higher average BP and develop HTN at an earlier age than white Americans. American Indians and Native Alaskans also have increased prevalence compared with white and Asian adults. Puerto Rican Americans have the highest rate of HTN-related deaths compared with other Hispanic populations. The rate of HTN-related mortality is similar between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Being born outside the United States, speaking a non-English language at home, and fewer years of living in the United States are associated with decreased prevalence of HTN.

Among those with HTN, 69.9% have received pharmacological treatment between 2005 and 2008.3 This was a slight increase compared with 1999–2002 when 60.3% of patients with HTN received pharmacological treatment. Patients without a usual source of medical care were the least likely to receive pharmacological treatment (19.7%). Overall disease control, defined as BP <140 mm Hg systolic and <90 mm Hg diastolic, in the United states was 53.5% between 2003 and 2010.2 Of those with uncontrolled HTN, 39.4% were unaware they had elevated blood pressures, 15.8% were aware they had HTN but were not being treated with medications, and 44.8% were aware they had HTN and were being treated with medications. Hypertension unawareness had highest prevalence among those who did not receive health-care in the previous year, those without a usual source of health-care, adults aged 18–44 years, and those without health insurance. Hypertension awareness without treatment with medications had highest prevalence among those without a usual source of health-care, adults aged 18–44 years, those of Hispanic ethnicity other than Mexican-Americans, and those without health insurance. Uncontrolled HTN despite awareness and use of medications for treatment had highest prevalence among Medicare beneficiaries, those aged ≥65 years, and those who received medical care ≥times in the previous year.2

Complications of Hypertension

HTN, along with dyslipidemia and smoking, is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Uncontrolled HTN may lead to end-organ damage such as myocardial infarction (MI), cerebrovascular accidents, and kidney failure. Other manifestations of uncontrolled HTN include retinopathy, angina, coronary revascularization, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, nephrosclerosis, and peripheral artery disease. Alinear relationship exists between BP and the risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke.4 Risk of death from ischemic heart disease and stroke begins when BP is >115/75. The mortality risk doubles for every increase in BP of 20/10 mm Hg. Other reports have indicated that there is a twofold increase in relative risk of CVD in patients with BP of 130–135/85–89 mm Hg compared to those with BP <120/80 mm Hg.

Classification of Hypertension

The seventh report from the JNC 7 defines four stages of BP measurements (Table 12–1)4 Lowering the BP can decrease the risk of complications related to HTN, but will not prevent all occurrences.

Table 12–1. JNC 7 Definition of Hypertension

Hypertension Treatment Goals

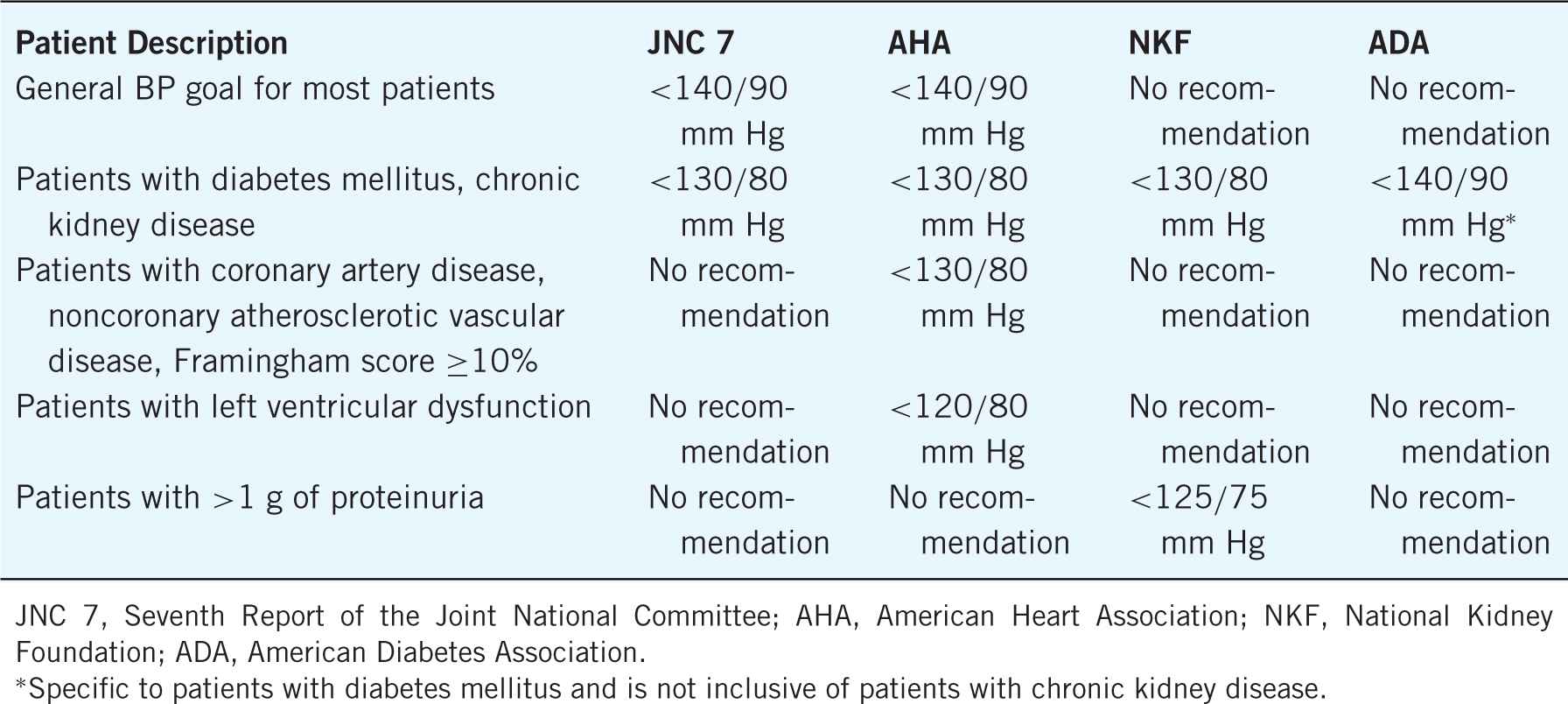

One of the difficulties of determining BP control stems from the multiple different guideline statements available for HTN. Table 12–2 lists the BP treatment goals according to JNC 7, the American Heart Association (AHA), the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), and the American Diabetes Association (ADA).4–7 The data to support the differences in the BP goals is lacking and primarily based on expert opinion and inferences made from observational studies. Future research should focus on the optimal BP goals for patients with CVD and CVD risk equivalents.

Table 12–2. Blood Pressure Target Goals

MEASURING BLOOD PRESSURE AND PULSE

MEASURING BLOOD PRESSURE AND PULSE

The most important aspect of a clinical service for HTN is the accuracy of the measurement of BP. The most widely used method to measure BP is the auscultatory method. This method was first called the Korotkoff technique, which was developed nearly 100 years ago. The basis of the measurement is the occlusion of the brachial artery by a sphygmomanometer to above the systolic pressure. As the cuff is deflated, blood flow is reestablished and is accompanied with sounds that are detected by a stethoscope. The first appearance of sounds marks the systolic pressure. The diastolic pressure is measured when the sounds disappear. This process seems relatively simplistic; however, it is important that the patient is positioned properly, the correct cuff size is selected, the cuff is placed in the correct position, and the observer is properly trained.8

Patient Position

The most reliable position for the patient to be in to measure the BP is in the seated position with back and legs supported and the feet uncrossed resting on a firm surface. The arm should be bare to the shoulder. If the shirtsleeve was raised to expose the upper arm, it should be loose to ensure it does not alter the BP measurement. The arm should also be supported and raised to be in level with the heart (middle of sternum). Prior to measuring the BP, the patient should be resting in this position for at least 5 minutes. The patient should also avoid caffeine, smoking, and exercise 30 minutes prior to the measurement, as these will raise the BP. The patient should be asked to remain silent while taking the BP measurement.

Cuff Size Selection

For most adults, the cuff size will range from adult small to adult large. Some adults may require the use of a child cuff or a thigh cuff, so it is important to have multiple sizes available. The cuff should encircle at least 80% of the arm. The use of a cuff that is too small may result in overestimation of the BP, and a cuff that is too large may result in underestimation of the BP. Most cuffs are now marked with line indicators to assist with determining the appropriate size. When the cuff is wrapped around the patient’s arm, the index line (runs along the edge of the cuff) should fall within the range lines (marked on the inside length of the cuff). If the index line does not fall within the range lines, a different sized cuff is needed. Table 12–3 lists the cuff size selection based on arm circumference.

Table 12–3. Cuff Size Selection Based on Arm Circumference4,8

Placement of the Equipment

The cuff should be placed 2 cm above the elbow crease. The midline of the bladder (usually marked on the cuff) should be placed over the brachial artery. The cuff should be tightly fitting when two fingers are underneath the cuff against the patient’s arm. The manometer should be in place such that the person measuring the BP can view it straight on and is not more than 15 inches away. The bell of the stethoscope should be placed over the brachial artery (inner aspect of the upper arm). If the bell of the stethoscope is in contact with either the cuff or the patient’s clothing, you will hear extraneous noises. To avoid these sounds, be sure the bell is only in contact with the patient’s arm and not touching other objects.

Taking a Quality Measurement

Obtaining a quality BP measurement should be easy now that you have positioned the patient properly, selected the proper cuff size, and placed your equipment in the correct locations. At this point, you need to determine what pressure to inflate the cuff to. To do this, first put the stethoscope down. You will palpate the radial pulse (outer aspect of the wrist) while inflating the cuff. Note when the pulse disappears, then deflate the cuff and note when the pulse reappears. This is the obliteration pressure. This step helps to avoid under-or overestimating the BP in patients who have an auscultatory gap (an intermittent absence of sounds after they initially appeared). Patients with an auscultatory gap have potential to have their systolic BP underestimated or their diastolic BP overestimated.

To measure the BP, place the bell of the stethoscope on the brachial artery and inflate the cuff to 20–30 mm Hg above the obliteration pressure. Slowly deflate the cuff (2 mm Hg/second) and listen for the Korotkoff sounds. There are five phases of Korotkoff sounds. The two phases that are used for BP measurement are phase 1 (initial appearance of sounds) and phase 5 (disappearance of sounds). Phase 1 is the systolic BP measurement and phase 5 is the diastolic measurement. To avoid overestimation of the diastolic BP and underestimation of the systolic BP, it is recommended to continue to slowly deflate the cuff and listen for additional sounds for 10 mm Hg after you no longer hear sounds. This process will assist with identifying an auscultatory gap if one is present. An auscultatory gap occurs when there is a period when Korotkoff sounds can no longer be heard, but then reappear at a lower pressure measurement. The sounds heard during this time are indicative of systolic BP. If sounds reappear during this time, continue to slowly deflate the cuff until the sounds disappear again. It is also advised to document the patient has an auscultatory gap to assist with future measurements of the BP.

In the event if you obtain a different BP in each arm of the patient, it is recommended you use the arm with the higher measurement for future assessments.

Quantity of Measurements

JNC 7 recommends for the diagnosis of HTN that two measurements should be obtained on different days.4 The AHA recommends obtaining at least two readings at least 1 minute apart in an outpatient clinical setting.8 The readings are then averaged to determine the documented BP. If the two readings are more than 5 mm Hg different, additional readings (1–2) should be obtained, then average all readings to determine the documented BP.

The AHA recommends obtaining the BP in both arms on the first encounter with the patient.8 This is due to the frequent occurrence of differences of BP between arms. If there is a consistent pattern of higher BP in one arm compared with the other, the AHA recommends using the results from the arm with the higher measurement as the documented BP.

A recent analysis was conducted to determine the certainty with which a BP measured using different strategies (home, clinic, research measurements) reflect the patient’s true BP.9 The study compared three methods of measuring BP based on location the measurement was taken (home, clinic, research center). The authors also examined the number of measurements and within patient variance. Results indicated that relying on only a single BP measurement in any of the three settings led to inappropriate classification of BP. Higher quantity of readings obtained from the patient increased the likelihood of properly classifying the patients’ BP. The authors concluded that to obtain >80% certainty of correctly classifying the BP control, the average of several BP measurements (5–6) is needed. They also indicated that this is best done using home measurements, as obtaining several measurements only minutes apart from each other in a clinical setting does not capture the true variation in BP seen throughout the day.

Measuring Pulse

The two most commonplaces to measure the pulse is the radial artery on the outer aspect of the wrist and carotid artery on the neck. You should place two fingers over the artery to palpate, making sure you do not mistakenly feel your own pulse. In patients with a regular rhythm, you can measure the pulse for a short duration (10 or 15 seconds), then multiply to obtain the number of beats per minute (bpm). However, in patients with irregular rhythm it is recommended you measure the pulse for a full 60 seconds to determine the pulse rate.

Measuring Orthostatic Blood Pressures10,11

There are times when a patient will present with symptoms of orthostatic hypotension that require the measurement of orthostatic BPs. This requires being able to position the patient in two positions (supine and standing). It should be expected that the patient’s diastolic BP will increase when transitioning between these positions. The patient should rest for 5 minutes in the supine position (lying down) prior to measuring BP and pulse. After lying still for 3 minutes, the patient should stand with an immediate repeat measurement of BP and pulse. Orthostatic hypotension is defined as a decrease in systolic BP of ≥20 mm Hg or diastolic BP of ≥10 mm Hg. The pulse may fluctuate during this time as well. A small change in pulse (<10 bpm) is indicative of baroreceptor reflex impairment. If the pulse increases >20 bpm, the patient is likely volume depleted. If the patient is not able to tolerate standing for 3 minutes, the patient should be referred for a tilt table test that simulates the same positional changes (supine to standing) without requiring the patient to rely on his/her own strength to transition between the positions.

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS FOR HYPERTENSION

LIFESTYLE INTERVENTIONS FOR HYPERTENSION

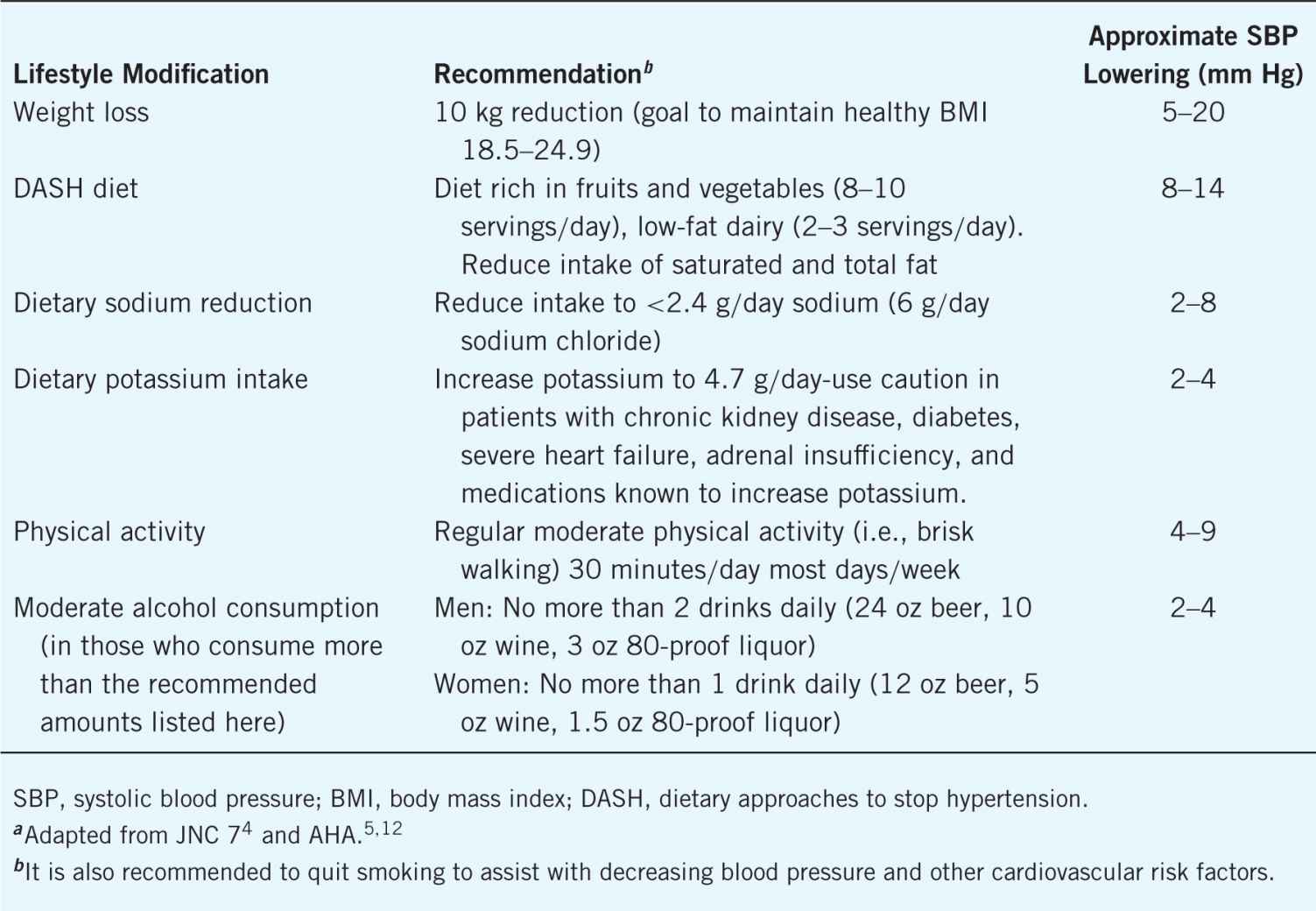

There are multiple different lifestyle modifications that will assist in reducing BP and assist with achieving BP treatment goals. Table 12–4 describes these modifications and anticipated systolic BP reduction that can be achieved. The lifestyle modification that has the greatest potential for improving BP control is weight loss. In order to achieve weight loss, it is important to educate patients on appropriate physical activity based on their current health status. For patients without restrictions on physical activity, the JNC 7 and AHA guidelines recommend moderate activity. The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans define moderate aerobic activity as working heard enough to raise your heart rate and sweat.13 At this point, the patient should be able to talk, but should not be able to sing. Examples of moderate aerobic activity include brisk walking (3 miles/hour), water aerobics, bike riding (<10 miles/hour), ballroom dancing, and general gardening.

Table 12–4. Impact of Lifestyle Modifications on Blood Pressure Controla

Food products have been linked with elevations in BP. The two most common are sodium and alcohol. The restrictions on consumption are listed in Table 12–4. Sodium restriction (<2.4 g/day) has shown to reduce systolic BP.12 Patients with the following characteristics receive the greatest systolic BP reduction with sodium restriction: blacks, middle aged, elderly, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Foods with reduced sodium content typically have increased potassium content. Increasing potassium intake can also assist to reduce the BP, with the greatest impact on black patients. There is a dose-dependent relationship between alcohol intake and BP with significant increases above two drinks daily (1 drink is equal to 12 oz beer, 5 oz wine, 1.5 oz of 80-proof liquor). Effects of restricting alcohol consumption have been observed in patients with and without HTN. Licorice can also elevate BP. Most patients are unaware of this, so it is important to educate them to avoid licorice until more literature is available to determine safe amounts to consume.

Counseling Tips for Success with Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle modifications can be difficult to implement and maintain. The anticipated benefit of each specific lifestyle modification can assist you with prioritizing the changes to implement. In order to maintain lifestyle changes, patients are typically more successful when small changes are made in a progressive manner, while ensuring a patient can maintain the first change before moving to another change. It is also helpful to have the patient involved in selecting what behavior to change. This empowers the patient to want to be successful with the behavior change and increases the likelihood of maintaining the change. For example, if the behavior change is to increase physical activity, you would first ask what activity the patient enjoys doing, then ask them how much time they can comfortably spend doing the activity weekly. You can educate the patient that the ultimate goal is to complete a moderate aerobic activity 150 minutes weekly, but that you will agree to start with the time that is feasible to the patient with the intent to slowly increase to the goal time.

There are multiple ways to assist patients with reduction in sodium intake. These include (1) avoid frozen meals and prepackaged foods; (2) select fresh or frozen vegetables instead of canned vegetables; (3) if you buy canned vegetables, buy low sodium products, and rinse prior to cooking; (4) do not add salt to the food once it has been prepared (take the salt shaker off the table); (5) reduce number of times weekly that you eat out; and (6) read food labels for sodium content.

MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

MEDICATION MANAGEMENT

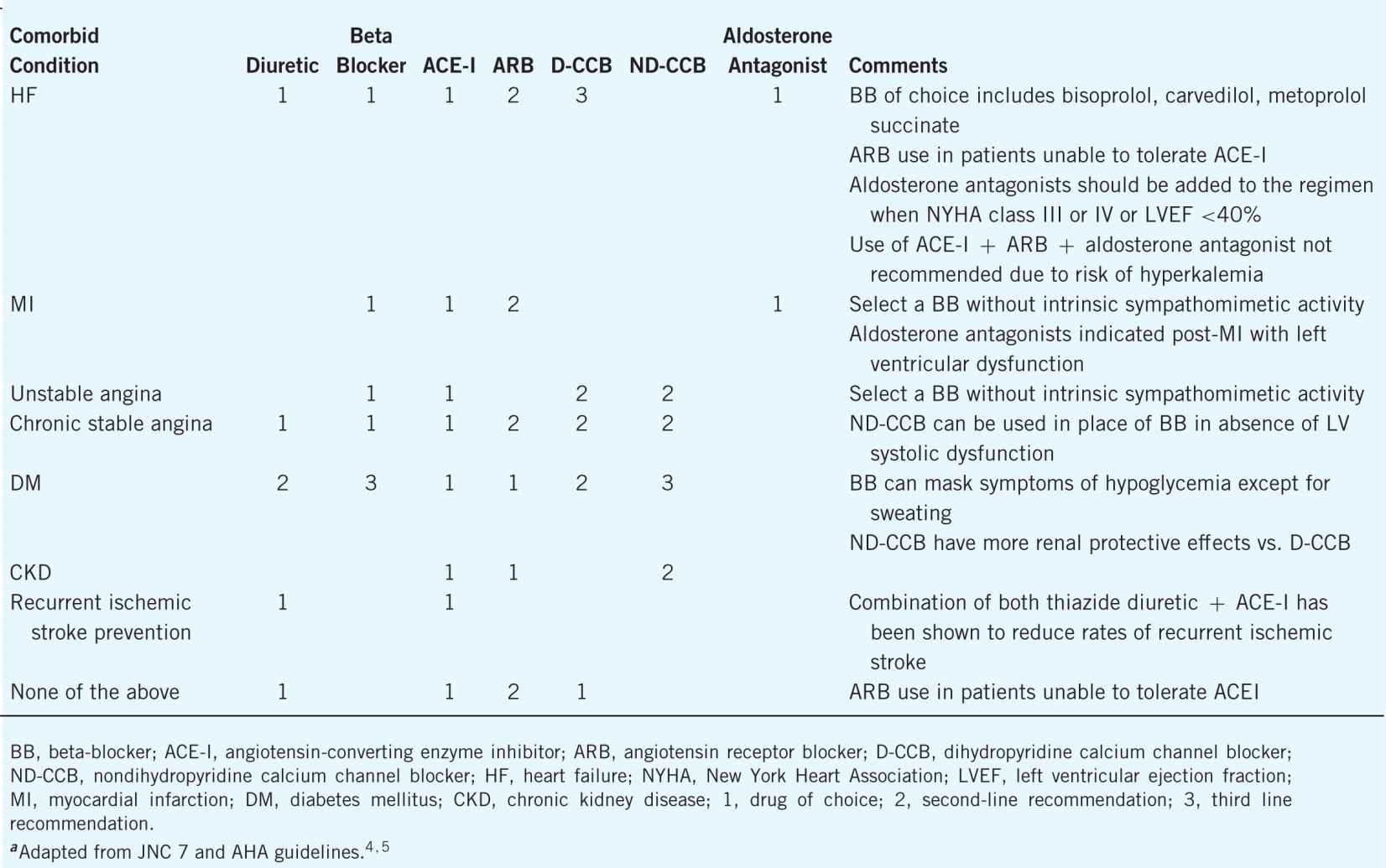

There are multiple medication classes available to treat HTN. Most patients will require more than one medication to reach their BP goal. In patients whose BP is ≥20/10 mm Hg above the treatment goal, guidelines recommend to initiate two medications from different structural classes. All other patients should be initiated on one medication. Selection of medications to treat HTN is often based on patients’ comorbid conditions. Both JNC 7 and the AHA detail recommendations on selection of medication class based on comorbid conditions. These recommendations are summarized in Table 12–5.

Table 12–5. Treatment Selection Based on Comorbid Conditionsa

First-Line Treatment—Thiazide Diuretics

For patients with no compelling indications, diuretics are the medication class of choice. Thiazide diuretics are more effective at lowering the BP compared with loop diuretics. However, thiazide diuretics are not effective with impaired kidney function (estimated CrCl <30 mL/minute, as measured by the Cockroft–Gault equation), in which case the loop diuretics should be used.

The selection of a thiazide diuretic should be based on evidence-based improvement in patient outcomes. The two most commonly used diuretics in the United States are hydrochlorothiazide and chlorthalidone. There has been recent debate over the interchangeability of these agents.14,15 There is little evidence that has directly compared the effectiveness of chlorthalidone with hydrochlorothiazide. It is also difficult to compare studies using either agent due to the differences in patient populations, study design, or medication combinations used. When comparing the evidence, stronger data supports the use of chlorthalidone in patients with HTN to prevent stroke, fatal, and nonfatal cardiovascular events. Of the trials published that used chlorthalidone, the two most notable are the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP)16 and Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack (ALLHAT).17,18 Chlorthalidone dose range studied in these trials was 12.5–25 mg/day.

The primary safety concern with thiazide diuretics is the risk of hypokalemia.14 The risk of hypokalemia is dose dependent with increasing frequency at higher doses. Hydrochlorothiazide rose to favor when studies linked high doses of chlorthalidone (50 mg/day) with sudden death related to hypokalemia. Hydrochlorothiazide has also been widely studied with mixed results (positive, neutral, negative). One possible reason for the differences in patient outcomes observed when comparing these diuretics are differences in their pharmacokinetics. Chlorthalidone has a significantly longer half-life (45–60 hours) and duration of action (48–72 hours) compared with hydrochlorothiazide (half-life 8–15 hours; duration of action 16–24 hours).15 Unfortunately, a head-to-head comparison of these two agents has not been conducted to definitively document the superiority, inferiority, or equality to improve patient outcomes. The available evidence supports either of these agents as appropriate for first-line use in patients without compelling indications for different agents. The recommended dose range for hydrochlorothiazide is 12.5–50 mg daily and for chlorthalidone 6.25–25 mg daily.15

Additional adverse effects include hyperuricemia and hyponatremia. Uric acid and sodium levels should be monitored more closely in patients with history of gout and hyponatremia and in patients who are on other agents that increase uric acid or decrease sodium. Thiazide diuretics may also cause hyperglycemia at doses beyond what is considered usual care. It is not unreasonable to monitor blood glucose more closely in patients with diabetes mellitus. The thiazide diuretics also increase urinary frequency, especially upon initiation or dose increases. It is recommended that patients administer the medications in the morning to prevent nocturnal diuresis.

First-Line Treatment—ACE Inhibitors, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers, and Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers

Selection of the second medication class in patients without compelling indications should be based on efficacy and tolerability. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (D-CCB) should be considered. JNC 7 and the AHA guidelines recommend these classes of medications because of supporting evidence to reduce at least one HTN-related complication.

When discussing the ACE-I class, it is generally accepted that each medication will produce similar results (i.e., there is a class effect). Medications in the drug class have been studied extensively in patients with HTN. Studies comparing ACE-I with placebo have noted a reduction in cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke. Reduction in these end points is thought to be unrelated to the BP lowering achieved (average BP reduction 3–5/2–3.6 mm Hg).5,16–18 Hyperkalemia is the most common adverse effect with ACE-Is. Hyperkalemia is more pronounced in patients with CKD or those taking other medications that increase potassium (ARBs, direct renin inhibitors, potassiumsparing diuretics, aldosterone antagonists). Dry cough is another common adverse effect that is caused by an increase in bradykinin. ACE-I-induced cough is sometimes confused with symptoms related to other disease states. It is advised that a detailed history of the onset of the cough is obtained prior to discontinuing the ACE-I. ACE-Is are contraindicated in patients with bilateral renal artery stenosis, as administration of an ACE-I in this patient population can induce acute kidney injury. A minimal raise in serum creatinine should be expected when ACE-I are initiation. However, if the serum creatinine increases >30% of the baseline value, the ACE-I should be discontinued. ACE-Is are FDA pregnancy category C in the first trimester and category D in the second and third trimesters. It is recommended that ACE-I should not be used in pregnancy. A rare, but serious adverse effect of ACE-I is angioedema (swelling of the tongue, mouth, throat). Patients with a history of angioedema should avoid ACE-I. If a patient experiences angioedema for the first time while taking an ACE-I, it should be discontinued immediately and the patient should not be rechallenged.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree