Learning Objectives

- Understand the history of international humanitarian assistance, including the key organizations involved and the principles and laws governing their work

- Know the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in populations affected by conflict, disaster and terrorism, and the key assessment strategies and public health interventions to consider

- Be familiar with prevention and preparedness approaches to disasters and acts of terrorism, and the roles and limitations of health interventions in conflict mitigation and humanitarian protection

- Be able to apply lessons learned to actual cases involving conflict, disaster, displacement, and terrorism

- Know where to go for updated information on the field of humanitarian assistance and its practice

Introduction

A health professional who wishes to make a positive impact in a disastrous situation faces many challenges. To begin with, goals must be defined. Is the aim of humanitarian medical work to reduce death, sickness, and suffering during a period of acute vulnerability? Or does the work extend to promoting the sustainable development of health systems and advancing peace, justice, and the respect of human rights? What if the choice to engage in relief work is motivated by religious, political, or military objectives?

Whether or not the aims of the work are narrowly or broadly defined, practitioners need excellent technical skills in evidence-based medicine and public health to avoid doing more harm than good. They must become rapidly familiar with the particular health problems threatening the population in question and the available resources (structural, financial, human, and organizational) and strategies that exist to cope with them. The most effective aid workers elicit and prioritize the health concerns of those being served: respect, support, learn from, and, when appropriate, guide colleagues; coordinate efforts; maintain flexibility; and strive for equity and efficiency while ensuring that assistance also reaches the most vulnerable populations. These aid workers also dedicate themselves to serving others while taking care to maintain personal health and equanimity in the midst of unfamiliar and stressful situations.

Experienced aid workers realize that their work may put them in danger, and they contribute to individual and group security by respecting sound security protocols, maintaining positive interpersonal relationships (with officials, community members, and colleagues), and collecting and sharing relevant information. In sum, the consummate humanitarian health worker combines compassion, commitment, and integrity with technical proficiency in promoting the delivery of the most appropriate, evidence-based, and up-to-date preventive and curative health services—a tall order in what are often very challenging environments!

A History of Humanitarian Work

The word humanitarian evokes a mysterious figure wearing a stained white coat and operating by candle light to the percussion of bombs and artillery rounds. The epithet that graces the frontispiece of the NATO war surgery handbook only reinforces this romantic view of wartime medicine: “[H]ow large and various is the experience of the battlefield and how fertile the blood of warriors in the rearing of good surgeons.”

In fact, the reality of most aid work differs radically from these images of adrenaline-charged, hands-on crisis medicine. More often effective relief work involves long-running efforts to prevent disease and facilitate access to care. Sometimes, far from being an ideal culture medium for medicine’s greatest achievements, the stresses and strains of aid work try the good will and challenge the ethical compasses of those involved in it.

Many groups with different philosophies participate in relief work. Most believe that humanitarian assistance is about relieving suffering and saving lives in times of conflict and in other situations where the entities typically responsible for providing the basic services fundamental to life are not doing so.

The history of the Red Cross Movement is intertwined with the development of modern humanitarian work and law. Its founder, Henri Dunant, was a Swiss businessman who encountered thousands of soldiers of multiple nationalities lying wounded near Solferino, Italy, during the War of Italian Unification in 1859. Dunant assisted the wounded and wrote a book about the experience, highlighting the need for a cadre of pretrained volunteers ready to assist in emergencies and calling for the establishment of an international relief society.1 His idea was that aid workers should be allowed to enter the battlefield unharmed as long as they agreed to remain neutral in a conflict.

The Red Cross Movement was born out of this idea, and humanity, impartiality, neutrality, independence and volunteerism are among the agency’s central principles. The Geneva Conventions, discussed later in this chapter, provide the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) with the mandate to protect and assist victims of both international and noninternational armed conflict. Its activities include, among many others, aiding civilians and prisoners (e.g., visiting prisoners of war to assess their conditions, transporting messages between family members divided by conflict, and providing medical and surgical assistance), helping to reunite families and trace missing persons, and spreading knowledge about humanitarian law. The ICRC is based in Geneva, Switzerland, and its delegates are usually Swiss. In addition, nearly 200 countries maintain a Red Cross or Red Crescent society. These societies are members of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. All of these organizations together form the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. To acknowledge Israel’s national emergency society Magen David Adom, an additional distinctive emblem of equal status to the Red Cross and Red Crescent, a square-shaped red frame on its edge known as the Red Crystal, was introduced in 2005 to the Movement.2

When Red Cross delegates document violations of the laws of war, they typically make recommendations in confidence to the responsible authorities. This policy of confidentiality helps the organization maintain its unparalleled access, but does it have its limits? During World War II, ICRC delegates visited concentration camps and did not publicly reveal what they saw. Keeping silent about extreme, persistent human rights violations can break into complicity, and now the ICRC occasionally goes public with its findings when governments fail to heed its concerns. For example, the Red Cross repeatedly questioned the legality and humanitarian consequences of the U.S. practice of undisclosed detentions and alleged interrogation techniques it said amounted to torture at facilities in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Bagram, Afghanistan, in the first decade of the 21st century. More recently, in 2010 the ICRC also condemned Israel’s blockade of Gaza as a violation of the country’s commitments under international law. Other relief organizations, such as the nongovernmental organization (NGO) Doctors Without Borders (in French, Médecins sans Frontières, or MSF) make “bearing witness” to human rights violations and advocating for populations at risk a central part of their humanitarian work. Often aid workers are the only independent outsiders to witness war crimes against civilians.

First and foremost, most assistance provided in conflict and disaster situations, particularly in the critical early days, is performed by local and national—rather than international—agencies and authorities. These include local health providers and health facilities, Red Cross and Red Crescent chapters, civil society organizations, militaries, police, and regular citizens. Too often their work is overlooked or sidelined by international actors coming in to “save the day.”

United Nations (UN) agencies also play a major role in humanitarian assistance. Founded in 1948, the UN emerged from the Cold War in the early 1990s as a key organization for preventing and resolving international conflicts. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has a mandate to protect refugees under the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. In recent years, the agency has also assisted the larger population of internally displaced persons (IDPs), who, unlike refugees, are displaced within their countries of origin. Table 15-1 describes the differences between refugees and IDPs. In 1997, the need for the UN to “act coherently” was recognized by then secretary-general Kofi Annan, who began reforming the agency to integrate humanitarian, peacekeeping, and political structures.3,4 UN agencies and other groups involved in humanitarian work are listed in Table 15-2.

Refugee: Defined under international law as a person who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.” Article 1, The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. |

In 2011 there were an estimated 10.5 million refugees, according to the UNHCR’s “The State of the World’s Refugees 2012: In Search of Solidarity.” |

Internally Displaced Person (IDP): An IDP often flees his or her home for identical reasons as a refugee and faces similar difficulties. IDPs, however, are defined by not having crossed an internationally recognized border. IDPs do not enjoy the legal protections conferred by the 1951 Refugee Convention, but increasingly they are, in practice, being provided with similar assistance according to the UN’s 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. According to UNHCR, in 2011 there were as many as 27.5 million IDPs—there were many more IDPs than refugees because of an increase in non-international versus international armed conflicts. |

Disaster: A situation or event involving the destruction of property, injuries, and deaths of multiple people, which typically overwhelms local capacity and necessitates outside assistance. Types of disasters include natural (e.g., hydro-meteorological, geological, biological), technological (e.g., mine explosion, chemical spill, other industrial accidents) and human-made (e.g., complex humanitarian emergency). |

Complex Humanitarian Emergency (CHE): A disaster that comes about at least in part due to human design. CHE is usually used to describe a disaster that involves multiple components such as large-scale displacement of people in the context of conflict, war, persecution, economic crisis, terrorism, political instability, or social unrest. |

Terrorism: There is no internationally agreed-upon definition of terrorism. A United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy adopted in September 2006 and reviewed in June 2012 describes terrorism as “activities aimed at the destruction of human rights, fundamental freedoms and democracy, threatening territorial integrity, security of States and destabilizing legitimately constituted Governments.” Terrorism often refers to attacks on non-military targets, such as the deliberate bombing of civilians and the taking and killing of hostages. These kinds of attacks would, if conducted during wartime, violate the laws of war and thus constitute war crimes. Terrorism is sometimes defined as violent, threatening, or criminal acts perpetrated against human victims but aimed against larger targets, usually States, and intended to create fear or terror in the minds of a population. |

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) (www.icrc.org), International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) (www.ifrc.org), national Red Cross societies |

United Nations Agencies: Many, including the World Health Organization (WHO) (www.who.int), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (www.unicef.org), Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) (), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (www.unhcr.org), World Food Programme (WFP) (www.wfp.org), United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (www.undp.org), United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (www.unwomen.org), United Nations Population Fund for Activities (UNFPA) (www.unfpa.org) |

International non-governmental organizations (NGOs): Many, including American Jewish World Service (AJWS) (www.ajws.org), American Refugee Committee (ARC) (www.arcrelief.org), CARE (www.care.org), Catholic Relief Services (CRS) (www.crs.org), Doctors of the World (also Médecins du Monde—MDM) (www.doctorsoftheworld.org), Doctors without Borders (also Médecins Sans Frontières—MSF) (www.doctorswithoutborders.org), International Medical Corps (IMC) (www.internationalmedicalcorps.org), International Rescue Committee (IRC) (www.rescue.org), Islamic Relief (IR) (www.islamic-relief.com), Mercy Corps International (MCI) (www.mercycorps.org), Oxfam International (www.oxfam.org), Save the Children (STC) (www.savethechildren.org), World Vision International (www.worldvision.org) |

Local and national non-governmental and civil society organizations: Many, different in each country |

United States government entities: US Agency for International Development (USAID) (http://www.usaid.gov) Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) (www.state.gov/j/prm/) |

Other governmental agencies: Humanitarian Aid Department of the European Union (ECHO) (http://ec.europa.eu/echo/index_en.htm) United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) (www.dfid.gov.uk/) Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) (www.jica.go.jp/english/) |

Intergovernmental organizations: International Organization for Migration (IOM) (www.iom.int/) |

Military operations: Peacekeeping Forces Monitoring Forces Belligerent Forces (parties to a conflict) Non-State Militant/Political Organizations Civilian-Military Operations Center (CMOC) Civil-Military Information Center (CMIC) |

Local and national government organizations: Ministries of Health Ministries of the Interior |

The hundreds of NGOs that exist have diverse histories and philosophies. Some of these nonprofit groups were born out of the Red Cross mold. Others offer assistance based on their members’ religious convictions to serve the less fortunate. Government agencies, such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Community Humanitarian Office, fund humanitarian assistance at least in part out of their cognition that promotes good will and good foreign relations in addition to its ability to improve lives.

Governments sometimes contract out assistance work to private for-profit companies as well as to nonprofits. Also, countries have offered the extensive logistical capacities of their militaries to assist in the aftermath of foreign disasters. Civil affairs units of armies involved in military actions in foreign countries may also provide aid to civilians, as Coalition forces did in Iraq.

From a national security perspective, promoting health can be a way to promote national or regional stability. The US Department of Defense has programs to support healthcare in overseas disasters and humanitarian emergencies in conjunction with USAID. However military goals and time frames often differ from development objectives, presenting collaboration challenges. Complexities in the civilian-military relationship are explored in Case Studies 1 and 2.

Local groups listed by the United States and other countries as terrorist organizations may also operate wings responsible for providing emergency assistance. For example, Kashmir-based militant groups ran many of the displaced person’s camps following the 2005 Pakistan earthquake, and Hezbollah provided aid to victims of the 2006 war in Lebanon. Foreign aid workers should be prepared to encounter these groups in the field.

In complex emergencies, humanitarian needs exceed the capacity of a single agency. In recent years, more and more agencies have become involved in humanitarian work. However, in emergency after emergency, the greatest criticism of the international relief response has been its poor coordination. As part of its reform efforts, in 2005 the UN set out nine thematic “clusters” covering key areas of humanitarian assistance in crises, including health, nutrition, and water/sanitation.* In the field, each cluster is led by a UN agency. The goal is to deliver humanitarian assistance in a cohesive and effective manner with a mandated and accountable lead agency. However evaluations of the cluster system suggest that although it has led to some improvements, it is costly and has many shortcomings.5

Although NGOs operate independently, most have agreed to adhere to a common code of conduct6 and minimum standards.7 On-the-ground humanitarian coordination is typically facilitated by the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs or by agencies set up by the governments of affected countries. Through the current coordination system, UN and non-UN actors engage in joint planning and prioritization of humanitarian response strategies and access shared funding pools. When arriving at an emergency, it is important to find out about interagency coordination meetings and look for Humanitarian Information Centers, which are often set up to provide a clearinghouse of information and maps and to keep tabs on “who’s doing what where.” With advances in satellite and communications technologies, there is an increasing role for technological experts to rapidly establish communications and information networks in emergencies.

The same agencies that respond to conflict-affected populations also tend to respond to major natural disasters. These often occur in parts of the world that are simultaneously affected by conflict, civil strife, and poverty.

In late 2002 and early 2003, humanitarian aid agencies prepared to provide assistance to Iraqis in the event of a US-led military offensive. NGOs disagreed about whether to accept US government funds to support their work. Some NGO leaders felt that taking the money would allow them to respond to a potential catastrophe, such as massive population displacement or a disease outbreak in a population that had already endured years of sanctions, isolation, and repression. Taking the funds might also give these NGOs a conduit to provide feedback to the United States about the needs of the civilian population. Other NGOs took sharply different positions. Their leaders argued that taking funding from a party to a conflict (a belligerent) would compromise the independence of the aid agencies and produce the appearance of taking sides in the conflict.

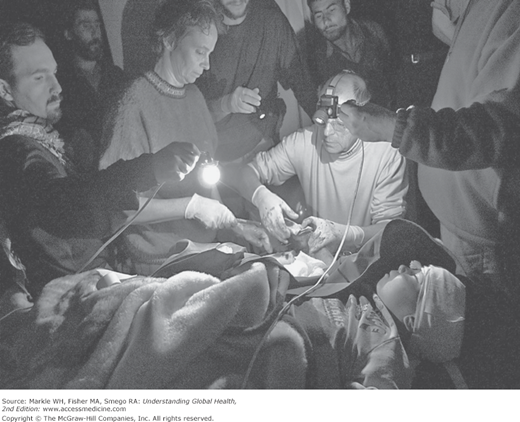

After the war began, the dilemma deepened. Aid workers disagreed among themselves about how they should relate to the US-led coalition and its civilian-military operations centers, which were involved in assisting Iraqi civilians. Aid workers cringed when the US-led coalition publicized their work as part of the coalition’s effort to win Iraqi “hearts and minds.” As insurgent attacks on aid workers grew, many worried about the blurring of the lines between the military, the political, and the humanitarian, not only in Iraq, but also in Afghanistan and other countries. Figure 15-1 depicts the medical services one American relief agency provided during the US-led bombing campaign in Afghanistan, ironically treating the wounds a small child sustained from the lingering munitions of a previous war.

Figure 15-1.

December 2001, Afghanistan: NGO personnel work under extremely austere conditions to stabilize a young Afghan boy. The boy was playing with an unexploded Russian heavy machine gun shell, which discharged, amputating his right hand. Apparently the boy’s friend struck the firing pin of the shell with a rock causing the explosion. Reproduced, with permission, from Andrew Cutraro Creative LLC. www.cutraro.com.

The 7.0 magnitude Haiti earthquake in January 2010 caused injuries estimated in the hundreds of thousands. Although Miami’s hospitals were only a short flight away, at first only Haitians with US citizenship were allowed to enter the United States for care. The United States deployed a vast hospital ship, the USNS Comfort, to the harbor of Port-au-Prince and began treating the critically ill and injured 1 week after the earthquake. Its gleaming white topsides accented with red crosses were a conspicuous symbol of US generosity. The Comfort and its 1,000-plus physicians and staff provided a range of advanced medical and surgical services, many of which were unavailable elsewhere in the low-income country. A surge of approximately 254 patients arrived within the first 72 hours straining the ship’s resources and personnel.8 Over a period of 40 days, a total of 872 patients were processed, more than 800 of whom were admitted for longer than a day. More than half of them went to the operating room, with many patients undergoing surgery multiple times.9 The ship’s equipment included a computed tomography scanner, interventional radiology suite, and a large pharmacy and blood bank.

However, painful ethical dilemmas arose. First, there were many more patients who needed help than the Comfort and other hospitals and clinics could handle. How to decide which patients to treat? Should the Comfort accept a smaller number of patients who needed very specialized resource-intensive care that only the ship could provide? Or should some complex patients be allowed to die in an attempt to maximize the overall number of patients treated? Who should make these decisions? A multidisciplinary Health Care Ethics Committee convened even before arriving in Haiti and was frequently consulted during deployment.10 Figure 15-2 depicts quandaries faced by American medical workers in Haiti.

Figure 15-2.

Collage of three pictures. (A) A soldier is lifted back into a navy helicopter after transporting a baby to a US government-run field hospital in Port-au-Prince, January 25, 2010. The baby arrived without family members and had untreated hydrocephalus, a condition unrelated to the earthquake requiring neurosurgery, a scarce specialty in Haiti prior to the earthquake. After a visit to the field hospital by CNN reporter and Atlanta neurosurgeon Dr. Sanjay Gupta, the baby was transferred to the USNS Comfort for a possible operation. (Photo by Dr. Sheri Fink.) (B) Dr. Chris Born, orthopedic surgeon from Rhode Island (left), and Dr. Carl Schulman, trauma surgeon from Miami (right), amputate the toes of a patient with gangrene at a US government-run field hospital in Port-au-Prince. Medical professionals faced dilemmas and tried to minimize amputations after being advised that Haitian amputees could be discriminated against and face challenges surviving in Haitian society after their operations. (Photo by Dr. Sheri Fink.) (C) A newborn baby with suspected neonatal tetanus is treated in the intensive care tent of a US government-run field hospital in Port-au-Prince, January 24, 2010. The field hospital ran short of oxygen, pediatric ventilators, and fuel for its generators, among other critical resources, leading to a scramble to procure more as medical professionals made life-and-death triage decisions. (Photo by Dr. Sheri Fink.)

Other dilemmas emerged. Representatives of the Haitian health ministry discouraged treating patients who would need advanced follow-up care of the type that could not be assured in Haiti after the Comfort’s departure. Should the ship’s medical staff heed this advice? Or should they instead save these patients’ lives and work to secure other resources for later care, taking advantage of the enormous outpouring of assistance and money available in the wake of the disaster? Some exceptions were made to the ministry’s guidance. Ship staff also provided some training and supplies to onshore medical workers for follow-up treatment and hospice care.11

Although many of the medical needs and ethical quandaries in Haiti were anticipated, communications with family members and referring doctors were problematic. In the chaos of the disaster, helicopters often whisked the ill and injured from one medical site to another without documentation, leaving family members behind.12 Family members were sometimes not permitted to travel to the Comfort with patients. Aboard the ship, only one in five patients had an accompanying escort. Healthcare workers had to make treatment and discharge decisions for children who arrived unaccompanied and could not give informed consent.

Initially there was no working phone number set up for relatives or referring doctors to call to check on the hundreds of patients being treated aboard the Comfort.12 Family members seeking loved ones were anguished. In one case, a young man flown to the ship simply disappeared. His family was later told he was dead on arrival to the ship, but they never received his body, were not given documentation, and were not permitted to view photographs a ship official said were taken of him before he was allegedly transferred to an overwhelmed Haitian morgue, which had no records of having received him.

The Comfort entered arriving patients into an electronic medical records system, but it did not have a practice of funneling information on patient disposition back to referring clinics. One man was flown to the Comfort from a US government-run field hospital for treatment of a severely fractured femur. His family members were not allowed to accompany him and returned repeatedly to the site of the field hospital to ask what had happened to him. They despaired for weeks until the man, who was ultimately transferred from the ship for treatment at a hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, spoke with a US reporter, who phoned them.

Finally, how and when to end the expensive mission?13 Bringing advanced medical care to a developing country that had little of it prior to a disaster presents inherent ethical questions: What level of care should be restored before it is acceptable to depart? What impact can such a level of care have on local healthcare practitioners? Where should patients be discharged when they no longer have homes, and where can they be transferred for needed ongoing treatment when local hospitals are overwhelmed? Moreover, should only acute “earthquake-related” health priorities be considered when timing a withdrawal, or should other needs be taken into account, such as those of patients with chronic medical problems that predated the earthquake and were inadequately treated in a low-income country, or the specter of ongoing injuries caused by earthquake debris, or the emergence of infectious epidemics like cholera?

The Comfort left Haiti 2 months after the earthquake, after senior leaders judged its humanitarian relief mission to be completed. At around the same time, all land-based field hospitals and clinics operated by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which had provided surgery, wound care, and childbirth services, also closed. Acute surgical needs were giving way to needs for rehabilitation and primary care best handled by the Haitian government, local medical institutions, and NGOs.

However, the departures were controversial. The Haitian government publicly supported these decisions. Government officials faced pressure from fee-for-service Haitian doctors who believed they had, paradoxically, lost needed business to foreigners providing free healthcare. In contrast, some aid workers and other Haitian doctors vehemently opposed the departures, pointing to the continuing need for skin grafts, complicated wound treatment, and the correction of surgeries performed hastily under less than optimal conditions.

Here are some other useful resources for more information:

Farmer P. Haiti after the Earthquake. Washington, DC: Public Affairs, 2011.

Katz JM. The Big Truck That Went By. New York: Palgrave, MacMillian, 2013.

Time magazine editors. Haiti tragedy and hope. New York: Time Home Entertainment, 2010.

Center for Naval Analysis. Assessment of Medical Support for Haitian Relief Operations. Alexandria, VA: CAN, April 2011. CRM D0024702.A4/1Rev.

US Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. Operation Unified Response-Haiti: Navy Medicine After Action Review. Washington, DC: BUMED, May 2010.

Department of Health and Human Services. Haiti—USNS Comfort Medical and Surgical Support, 2010. www.hhs.gov/haiti/usns_comfort.html.

Pan-American Health Organization. Health Response to the Earthquake in Haiti: January 2010: Lessons to Be Learned for the Next Massive Sudden-Onset Disaster. Washington DC: PAHO, 2011. http://www2.paho.org/disasters/dmdocuments/HealthResponseHaitiEarthq.pdf.

Sternberg S. Haiti’s ‘Floating Hospital’: Tough Questions on the USNS Comfort. USA Today, 2010. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/health/2010-01-27-1Acomfort27_CV_N.htm.

US Naval War College. Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Relief Conference. Rhode Island, May 2011. http://www.usnwc.edu/ha.

Terrorism is a major concern for international aid workers, not only because it leads to morbidity and mortality among civilians, but also because aid workers themselves are increasingly the targets of terrorists. More than 100 aid workers per year have died in recent years, constituting a tripling over a decade, according to a UN study,14 and the number of kidnappings has also markedly increased. These disturbing trends may, at least in part, be explained by the perceived blurring by belligerents of the humanitarian, political, and peacekeeping mandates of the UN that has come with the processes of UN integration and humanitarian coordination. In Baghdad, Iraq, in 2003, both the UN compound, which housed the UN’s political and humanitarian wings, as well as the ICRC headquarters, were targeted by suicide bombers. Since 2005, violence against aid workers has grown more sophisticated and lethal and has been concentrated in a small number of volatile countries, including Afghanistan, Sudan, and Somalia.

For their protection in conflict zones, humanitarians have traditionally relied primarily on an invisible shield forged from tradition and from the “laws of war,” which state that noncombatants, and particularly relief workers, are never legitimate military targets. Humanitarians typically prefer to avoid security measures that involve armed protection. Aid workers take pains to distinguish themselves from the military, often refusing military escorts, and trusting instead that their widely recognized neutral and impartial status will protect them.

Because belligerents have played on the vulnerability of relief workers—the fact that they are often soft targets without much in the way of armed protection—the magnitude and frequency of the attacks has forced a belief among some workers that the promise of protection given by the Geneva Conventions is inadequate. Some aid workers have felt compelled to use armed guards for protection and other pragmatic options to avoid having to withdraw and leave the embattled civilians they have traveled across the world to assist. Sadly, many aid agencies have withdrawn from countries where violence has surged in recent years such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Somalia because of security concerns and a sense that the “humanitarian space” needed to do their jobs according to their principles has been lost.

The major bodies of law that apply to humanitarian work, particularly in times of war and conflict, include international humanitarian law, refugee law, and human rights law.15

IHL requires aid workers to identify themselves with certain emblems for their protection. However, in recent years, aid workers have been specifically targeted by militaries, other armed groups, and terrorists. Some agencies have removed all identifying marks from their clothing and their workplaces. What do you think? To foster trust in beneficiaries, humanitarian workers long eschewed guns and guards, relying instead on the respect of international law and strong relationships with the community for protection. However attacks on aid workers have occurred frequently in recent years. Humanitarians must consider whether and when hiring private security forces or accepting military escorts will make them more secure and effective in their work, or conversely risk compromising their independence and their access to the most vulnerable populations. How would you decide the best way to ensure your team’s security—both for international and national staff? |

International humanitarian law (IHL) includes, most importantly, the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocols I and II (1977). In 2006, the Geneva Conventions achieved universal acceptance. In 2012, the world’s youngest state, South Sudan, joined all others informally agreeing to abide by them. IHL requires that belligerents respect the four principles of discrimination between military and non military objects, proportionality (the degree of force used should be proportional to anticipated military advantage and should be weighed against the risk of “collateral” damage to civilians), precaution to minimize non-combatant risk, and protection of noncombatants.

Noncombatants include not only civilians having nothing to do with the fighting, but also injured and captured fighters, refugees, and humanitarian, medical, religious, and journalistic personnel carrying out their duties in the conflict area. IHL gives Red Cross workers and other humanitarians the right to assist war-affected populations without interference or harm, and also certain responsibilities: mainly to practice in accordance with medical ethics and not get involved with fighting (apart from self-defense or protection of patients).

Refugee Law (Convention on the Status of Refugees, 1951, and the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1967) gives nations the duty to grant asylum, thus protecting refugees when their home countries have failed to do so.

Human Rights Law [based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; and many other instruments, including those related to genocide (1948), racial discrimination (1965), civil and political rights (1966), economic, social, and cultural rights (1966), women’s rights (1979), children’s rights (1989), torture (1984), and internal displacement (1998)], protects certain “non-derogable” rights that are not to be limited under any circumstances, including during time of war or national emergency. These include the rights to life; juridical personality and legal due process; and freedoms of religion, thought, and conscience. Human rights law also prohibits torture, slavery, and degrading or inhuman treatment or punishment in wartime as well as peace time.

The protection to be afforded noncombatants during war time is, at base, protection against suffering and death, whether from physical violence, wartime deprivations, or the violation of inalienable human rights. The responsibility for providing this protection rests primarily on states and members of armed forces. They in turn must allow humanitarian organizations to operate whenever noncombatant needs outstrip the ability of states or militaries to provide for them.

Medical aid workers operating in conflict-affected environments should observe medical neutrality. The concept derives from international human rights, humanitarian law, and medical ethics. It refers to the idea that medical professionals must uphold medical ethics (e.g., beneficence, autonomy, nonmalfeasance, and justice) and treat patients according to need, without discriminating based on nationality, religion, ethnicity, political views, or even their status as members of a particular military force. Healthcare professionals must not cause harm to their patients or participate in torture. Healthcare clinics or hospitals that are used by the military to store weapons or conduct attacks can lose their protected status.

In recent years, the number of refugees falling under the mandate of UNHCR has varied—from nearly 18 million in 1992 to just over 9 million in 2004 to 10.5 million in 2011. However, the number of IDPs worldwide has increased dramatically—from little over a million in 1982 to an estimated 27.5 million in 2011. Various factors may have contributed to this trend, for example more international recognition of IDPs as a group; the tendency of potential asylum countries to close their borders to refugees; and an increase in internal conflicts and civil wars where civilians are specifically targeted. It is important to note that situations of displacement have often stretched on for many years or even decades, highlighting the need for international healthcare assistance and—more importantly—efforts to attain just and durable solutions far beyond the period in which worldwide media attention focuses on the plight of the displaced.

Another worrying trend is the increase in proportion of civilian over military casualties of wars and conflicts. Although statistics are difficult to pin down, there is general agreement that there has been an enormous heightening in the proportion of civilian as opposed to military casualties of conflicts. Most worrisome, civilians are often the intended targets of hostilities, in absolute violation of the fundamental principles of international humanitarian law. Despite the promises made by governments and the UN following the failure to protect civilians in the 1990s in genocides that occurred in such places as Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the failure of the international community to act decisively to protect civilians in armed conflict was made clear again in the first decade of the 21st century in places such as Darfur, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

What did develop, however, was so-called soft law, including the emergence of a new international security and human rights norm, the Responsibility to Protect, or “R2P.” R2P is based on the principle that state sovereignty entails responsibilities, specifically to prevent the four mass atrocity crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. Both the UN General Assembly (in 2005) and the UN Security Council (UNSC; in 2006) formalized their support for R2P by adopting the following statement: “We are prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner…should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities are manifestly failing to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.”

This conviction was borne out in March 2011 when NATO took military action against the Gaddafi regime in Libya under approval of the UNSC after it found Libyan authorities to have failed in their responsibility to protect their own population. This intervention proved controversial on legal and moral grounds, as did the apparent inconsistency highlighted by the lack of intervention in early 2012 by the international community in the bloody internal conflict in Syria.

An increasing number of natural disasters, too, have been reported in the past several decades, affecting an increasing number of people, according to the Center for Research in the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in Belgium. Interestingly, while the number of people affected by natural disasters and the estimated financial cost of damages have increased over this time, the number of people reported killed by them has declined steadily.16 Extreme poverty is among several factors that magnify human suffering in disasters. To better understand these factors, specialists separate out three aspects of disasters: The hazard, which is the physical or bio-physical event itself (e.g., flood, earthquake, tsunami); exposure, which is the degree to which people are in danger of falling in the path of a hazard (e.g., the number of people living in disaster-prone areas, how well built their houses are); and vulnerability, which is how susceptible people are to the event due to physical, social, economic, and environmental factors (Do people have the means to escape? Are warning systems in place? How well do medical systems function?). In addition to natural disasters, technological disasters such as industrial accidents affect a great number of people each year worldwide, although the trend has been decreasing over the past decade.17

*The nine clusters are agriculture, camp coordination and management, early recovery, education, health, nutrition, protection, emergency shelter and water, and sanitation and hygiene. Two common clusters are emergency telecommunications and logistics.

†Editors’ note: Complex humanitarian emergencies are called complex for a reason. The Haitian situation was very difficult, and each aspect was complex and had many sides. In addition to the references cited here, this case study is based on reporting and interviews by author Sheri Fink from January-March, 2010. This information is very important and helps us understand how much we still have to learn. In this short space, however, we cannot begin to give a complete picture of the whole operation, nor can we give any official view from the US Navy. For more reading on this subject, several references are listed at the end of this case study.

Preparedness and Prevention

Often preparedness and prevention are the last things international health workers think about when responding to a crisis. However, lightning often strikes twice, with populations affected by one disaster later experiencing another. In the United States, many of those who fled Hurricane Katrina in September 2005 were, several weeks later, displaced by Hurricane Rita. Here are just a few ways international aid workers may promote preparedness and prevention:

- Build the response capacity of local health agencies, hospitals, clinics, and caregivers

- Prioritize physical improvements for health facilities and other critical structures

- Promote safe housing solutions for displaced populations

- Educate the public about potential disaster threats and how to respond to them

- Build human bridges between conflict-affected areas, for example, by hiring staff from various sides of a conflict, bringing together health workers for training programs, and supporting ceasefires for vaccination campaigns

Medical and Public Health Priorities

Humanitarian assistance is both an ancient moral practice and an increasingly professional social scientific discipline. The failure of humanitarian agencies to avert widespread death and suffering among refugee populations in the 1990s (in particular among Rwandan refugees in what was then Zaire) led to calls for minimum standards in aid, increased qualifications of aid workers, and better research on what does and does not work to decrease morbidity and mortality in affected populations. A result of this work was the 1997 Sphere Project, which led to a widely used handbook of minimum standards in relief. Now in its third edition released in 2011, it covers water supply, sanitation and hygiene promotion, food security and nutrition, shelter, settlement and nonfood items, and health action.

Sphere is based on the idea that aid workers provide assistance not just out of their own desire to relieve human suffering, but also because disaster-affected populations have a right to human dignity and therefore to receive quality assistance. The goals of Sphere are stated in its Humanitarian Charter, which focuses on enhancing the quality of protection and assistance of those affected by disaster and promoting the accountability of aid workers to those they seek to help.

Groups that join Sphere agree to a common set of principles based on international law, including the right to life with dignity; the distinction between combatants and non-combatants; and the principle of non-refoulement (that refugees must not be forced to return to the country they fled if a danger still exists for them there). The groups also commit to minimizing the adverse effects that aid delivery has too often had in the past, such as paradoxically leaving civilians more vulnerable to attack or contributing to hostile activities.

Sphere is not without its critics, including members of MSF and some other organizations. They argue that technical proficiency is not the only means by which humanitarian action should be judged—humanitarians should be held equally accountable for showing compassion, promoting human solidarity, bearing witness to human suffering, and upholding justice.

Although previously lacking emphasis on physical protection, the latest edition of the Sphere handbook includes four “Protection Principles” to guide the work of humanitarians: “Avoid exposing people to further harm as a result of your actions”; “Ensure people’s access to impartial assistance—in proportion to need and without discrimination”; “Protect people from physical and psychological harm arising from violence and coercion”; and “Assist people to claim their rights, access available remedies and recover from effects of abuse.” Human rights groups have also emphasized the importance of measuring and assessing human rights violations in the context of emergencies.

In recent years, epidemiologic surveillance and research have deepened understanding of the specific causes of morbidity and mortality in war and disaster-affected populations (Table 15-3). The most robust data come from camp situations, which have proven to be ideal settings for epidemiologic research while at the same time often being dreadful living arrangements for displaced populations.

Infectious diseases Traumatic injuries Emotional distress Malnutrition/micronutrient deficiencies Exacerbations of chronic illnesses (often due to treatment interruption). |

Major infectious threats with epidemic potential include diarrheal infections (particularly cholera), measles, respiratory infections, and malaria. Infectious disease outbreaks tend to be less common among populations displaced by natural disasters than by war. The preexisting health profile of a population affects its experience during displacement. For example, populations with poorer pre-disaster health status often have a higher proportion of problems due to infectious diseases, particularly vaccine-preventable diseases, and greater overall vulnerabilities if they are also malnourished.