Learning Objectives

- Describe the global burden, causes, forms, and impact of human trafficking

- Identity the health implications (public and individual) of human trafficking

- Describe the interventions used to combat human trafficking, and give examples of public health prevention approaches

- Identify some key initiatives and partners in anti-human trafficking

- Describe the role of demand reduction in combating human trafficking

Case Examples

Bopah lived in a rural village and married at age 17. Her husband took her to a hotel in another village in Cambodia and left her. Bopah discovered the hotel was a brothel and tried to escape, but she was forcibly detained and told she must pay off her price. Bopah’s “debt” increased due to charges for her food, clothing, and other necessities. Bopah could not leave. Several years later, ravaged by disease, she was thrown out on the street.1

Alin is a 14-year-old boy from Romania who is sexually exploited by his father and sold to foreign tourists who frequent a section of Milan known for child prostitution. Alin’s father receives 40 euros each time his son is picked up. He uses the money for food and cigarettes. Under the Trafficking Victim’s Protection Act of 2000 and international covenants, child prostitution is, by definition, a form of human trafficking.

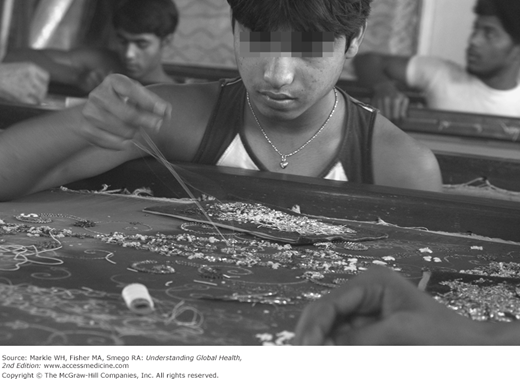

Young men sew beads and sequins in intricate patterns onto saris and shawls at a “zari” workshop in Mumbai, India (Figure 5-1). The boys who arrive by train from impoverished villages across India often work from 6 in the morning until 2 in the morning the next day. Some sleep on the floor of the workshop. If they make the smallest mistake, they might be beaten. All say they work to send money back to their families, but some employers are known to withhold their meager pay.

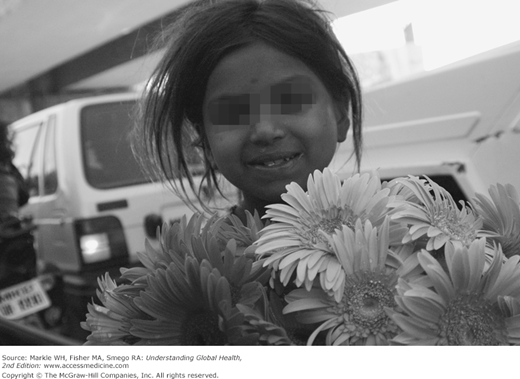

Street kids, runaways, or children living in poverty can fall under the control of traffickers who force them into begging rings (Figure 5-2). Children are sometimes intentionally disfigured to attract more money from passersby. Victims of organized begging rings are often beaten or injured if they do not bring in enough money. They are also vulnerable to sexual abuse.

Debbie was a 15-year-old when she was abducted from her suburban Phoenix, Arizona, home. Shortly thereafter, she was threatened, raped, and crammed into a small dog crate. Her captors forced her to work as a prostitute. Finally local police followed up a tip and found Debbie, shaking, locked in a drawer under a bed.2

Introduction

Every year as many as 27 million men, women, and children around the world, including the United States, may be subject to force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of sexual exploitation or forced labor.3 A modern-day form of slavery, human trafficking is sometimes referred to as an epidemic that is “hidden in plain sight.” The International Labor Organization (ILO) conservatively estimates that some 21 million persons are labor trafficked around the world.4 Trafficking victims are of all ages, races, nationalities, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and educational levels. Their perpetrators come from the same categories. No group is exempt from the risk of being trafficked or the choice of being a trafficker.

Human slavery has a long history around the world. Written accounts of labor trafficking date back to thousands of years before Christ when a young man named Joseph was sold by his brothers to travelers en route to Egypt and then resold by those buyers to other traders for slave labor. Over the centuries, warring tribes captured people and sold them to others; slave traders in the 1700s and 1800s plied the waters between Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean; the history of the United States is marred with tragic years of slavery; and today traffickers still troll inner cities, impoverished areas, and highways, looking for someone to entrap and then sell. Indeed, the for-profit sale of a person as a commodity is not limited to time, geography, ethnicity, economic status, or gender.

Over the decades, various countries, parliaments, legislative bodies, as well as individuals in the public eye and those working quietly and covertly, have sought to rid their world of this injustice. Nevertheless, the reality of the 21st century is that slavery in the form of human trafficking still exists. It would seem inconceivable that people today would still enslave others or be subject to exploitation by others for profit. Yet unscrupulous employers, pimps, and other opportunists recruit, control, transport, hold hostage, and torture other human beings against their will. Their victims have been made vulnerable by poverty, civil conflict and war, unemployment, corruption, discrimination, gender inequities, or just the hope for a better future. Deception, force, or coercion change their dreams and another’s false promises to harsh realities from which physical, emotional, and psychological escape is very difficult.

In some countries, the pressures for economic survival or the need to break out of poverty can be the risk factor for being trafficked. People may be approached by a relative, neighbor, or business person proposing that they or a family member, often a child, could benefit from an educational opportunity, vocational training, or employment—for example, on a cocoa plantation, on a fishing boat, in the entertainment world, hospitality business, or textile industry. The recruiter pays the family for that person and then arranges for transport to a larger place, the capital city, or even another country. Once there, the trafficked person may be initially placed in a hotel or restaurant setting but transitioned out to a brothel or forced to labor in a garment or carpet factory or as a camel jockey. The buyer of the trafficked person may just be an intermediary, reselling the victim, or may be the end beneficiary of the sex or labor services. Wages earned are retained by the employer or trafficker for payment of expenses in transit, such as transport, visas, and lodging, and then for recurring costs (e.g., shelter, food, clothing) from which the trafficked person can rarely recover, thereby indenturing him or her indefinitely.

It is a common misperception that to be trafficked, a person must cross borders. Trafficking can be a very local phenomenon. Children can be trafficked for agricultural or fishing labor within the environs of their home village. Teen runaways can be deceived by a neighborhood boyfriend, then forced to have sex with his friends, who pay her boyfriend for the opportunity to rape; they can abuse her in the house next door. Roving armies and guerrilla bands can forcibly conscript children living in the path of civil conflict and war-torn areas to be cooks, soldiers, sex slaves, or murderers.

Why would people buy and sell each other? Unlike drugs and arms, people are commodities that can be used over and over again, without final transfer to the buyer. Human trafficking is very profitable. It is estimated to be the third most profitable “business” after trafficking in drugs and arms. The ILO estimates that transnational criminal networks and local gangs take as much as US$32 billion in profits from labor and sex trafficking enterprises. Hidden from authorities, these profits are not taxed or regulated. Like drugs, arms, and any other commodity, there is a so-called shelf life. Humans who have been trafficked repeatedly can reach their expiration date through homicide or suicide, a disabling injury or illness, or by virtue of having reached an age where their usefulness is exhausted. For example, their fingers are no longer able to weave carpets, their body weight is too much for a camel jockey, their sexual organs diseased or damaged from many customers, or their backs broken by heavy loads or occupational hazards. They have been called “disposable people.”5 The trafficker goes back to his market for a new supply, and the cycle starts over again.

Definitions of Terms

Although the term trafficking might suggest transportation, trafficked persons can be born into a state of servitude, placed in an exploitative situation, or have consented initially to a job, only to find that they are forced to work without wages, rights, or decent working conditions. In 2000, the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress, and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children (the Palermo Protocol) and the U.S. government’s Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2001 describe this compelled service as “force, fraud, or coercion.” The TVPA defines “severe forms of trafficking in persons” as:

Sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age; or,

The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.

By definition in the Palermo Protocol and the TVPA, in the case of a minor (under age 18 years), prostitution is a crime, whether or not there was consent.

The term human trafficking is not the same as smuggling where a person is willing to be transported to another location, usually across international borders, and has paid someone to take them there. In human trafficking, a person may be willing initially to be moved and may have paid something in advance. The deception, fraud, or coercion that evolves within that process, however, is the distinguishing hallmark.

The terms country of origin, transit, or destination are used to broadly classify countries and trafficking movement. A country can serve in all three roles, although some countries tend to be source countries, and others tend to be destination countries. For purposes of foiling investigators and law enforcement, traffickers may use some countries as places of transit. The use of fake passports and visas, coupled with cheap ticketing for transport and low-budget accommodations, aid in the covert nature of trafficking. Many people, even unknowingly, can be involved along the way, making it difficult to identify the head of the criminal activity. Yet they are all traffickers. In China, the lead traffickers are sometimes referred to as “snakeheads,” signifying their leadership role and implying the venom they can inflict on those not cooperative with their evil intent and purposes.

Not all the terms used in trafficking are uniformly agreed upon. Some may choose to use the term trafficked person; others use the term victim. Although this latter term can appear stigmatizing, this term legally differentiates a victim from a criminal.

Figure 5-3.

This desperate mother traveled from her village in Nepal to Mumbai, India, hoping to find and rescue her teenage daughter who was trafficked into an Indian brothel. Nepalese girls are prized for their fair skin and are lured with promises of a “good” job and the chance to improve their lives. “I will stay in Mumbai,” said the mother, “until I find my daughter or die. I am not leaving here without her.” (Courtesy of Kay Chernush for the U.S. State Department. http://www.gtipphotos.state.gov.)

Forms of Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is categorized as either labor trafficking or sex trafficking. One category of trafficking does not preclude the other because some victims who are initially labor trafficked can also be sex trafficked. Children who were abducted or forcibly recruited to serve as combatants, cooks, messengers, or spies can also find themselves sexually abused by their troops. For migrant workers, invalid contract terms and unsafe working conditions are setups for abuse; imposition of huge debts that they are required to work off may be the path of debt payment through sexual favors. Domestic servants in an informal workplace may be physically, socially, and/or culturally isolated. As a result, their employer may take advantage of them, forcing them to live in small quarters and/or coercing them to provide sexual services to the employer or his or her guests and family.

Three forms of exploitative practices are found in labor trafficking: bonded labor, forced labor, and child labor. Bonded labor, or debt bondage, is the least known but most widely used form of slavery. The victim’s work is meant to be their means of repayment for a loan or service; however, no contractual terms exist to define the worth of their services as repayment, and their services do not liquidate their debt. In other words, their debt is always greater than the value of their services. Debt bondage can entrap not only individuals but whole families and even generations of people. Forced labor is a situation in which force, threat, or punishment mark the relationship between the so-called employer and worker. Freedom is restricted, and ownership of the person is exerted. Examples include sweatshops and domestic servitude, and they are found in some hotel and restaurant industry work, the garment industry, agriculture, and even street begging.

Many millions of children between 5 and 17 years of age are likely victims of labor trafficking. Child labor interferes with the physical, mental, spiritual, and social, educational, and moral development of children. It can be manifest in industries that require the nimbleness of children’s fingers, such as carpet weaving, or their small size and weight, such as camel jockeying, or simple dull tasks such as breaking up stones into smaller pieces to make sidewalks or roads, or carrying clay bricks to kilns. Children who live in remote and rural areas can also be labor trafficked to help with fishing or plantation work, such as cocoa plantations in West Africa. Their remoteness makes them less visible to outsiders who might recognize that these children are not in schools. Many children do help with family businesses or informal employment as street vendors, but when such work predominates and drives their days, prohibiting a normal childhood of play and school, then it may be labor trafficking. Children can also be the mules for transport of illicit drugs or arms, or serve as child soldiers in countries where civil conflict requires conscription to increase the number of combatants, or to serve the troops, or both. Child soldiers may be sexually molested to threaten them into service. To desensitize them to the killing and horrors of war, they may be forced to kill a parent, a friend, or a stranger, as part of a gang initiation and as part of the message of “kill or be killed.”

| “Migrant workers from Nepal and other countries are like cattle in Kuwait. Actually, cattle are probably more expensive than migrant workers there. No one cares whether we die or are killed. Our lives have no value.” – Nepalese man trafficked to Kuwait, during an interview with Amnesty International. |

Sex trafficking may be a component of sex tourism, gang activity, high-end escort services, or simply as a means to make a profit by exploiting another human being. Runaway adolescents are vulnerable to being sex trafficked. Even if their initial conditions seem favorable and their new relationships seem trustworthy and generous, they are ultimately being groomed to be sold and brutally seasoned to sexually service multiple customers. Sex trafficking tends to receive more media coverage because of its sensational nature, but it is not as common as labor trafficking. It is estimated that several hundred thousand people are trafficked within the United States each year. Given stricter labor laws in the United States, sex trafficking may represent a higher percentage of all trafficking there compared with other countries.

| “I walk around and carry the physical scars of the torture you put me through. The cigarette burns, the knife carvings, the piercings. . how a human being can see humor in the torture, manipulation, and brainwashing of another human being is beyond comprehension. You have given me a life sentence.” – Victim of trafficking in the United States, to her trafficker at his sentencing. |

Usually not considered as human trafficking, organ trafficking still entails the use or abuse of humans through the sale of body parts for transplantation. The demand for organs such as kidneys exceeds the global supply. Desperately poor people may see the sale of one of their kidneys as a means to better themselves economically. Recruited by traffickers in urban slums, they are promised a free round-trip ticket to a second- or even first-world hospital where their organ will be skillfully removed and provided to someone else in need. The combination of apparent altruism for a needy recipient with an economic benefit to the donor can be attractive to a vulnerable person and may lend an air of legitimacy. The particulars of their postsurgical care, however, are lacking. Follow-up for surgical and medical complications, or compensation beyond the organ donation, are not part of the package by the organ trafficker. Costs of care to the donor once returned to their home country may well offset any initial gains. In some instances, children are sought and kidnapped for organs or body parts, not so much for transplantation but for perceived magical powers.

The Magnitude of the Problem

In June 2012, the ILO released a new global estimate of 20.9 million forced labor victims.6 The ILO notes that this is a conservative estimate for this largely hidden crime. The ILO’s definition of forced labor includes sex trafficking (forced commercial sex). Women and girls represent an estimated 55% of forced labor victims; men and boys represent 45%. An estimated 74% of victims are adults (18 years and older); children make up the other 26%. The Asia-Pacific region has the largest number of forced laborers (56% of the global total), followed by Africa (18%), Latin America and the Caribbean (9%), the Developed Economies and European Union (7%), Central, Southeast, and Eastern Europe (non-EU) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (7%), and the Middle East (3%).

About 90% of all victims are exploited in the private economy, by individuals or enterprises. Of those exploited in the private economy, 22% are victims of sex trafficking; 68% are victims of labor trafficking. The remaining 10% of all victims are in state-imposed forms of forced labor, such as in prisons or in work imposed by the state military or rebel armed forces. Some 44% of the total number of forced labor victims have been moved internally or internationally; 56% are subjected to forced labor in their place of origin or residence.

The Public Health Model of Human Trafficking

As in traditional public health models, especially for infectious diseases, one can also think about human trafficking in epidemiologic terms: the host, agent, environment, and vector. Using malaria as an example, the agent is the parasite Plasmodium, the vector is the Anopheles mosquito, the environment is the warm and stagnant water where the mosquito can breed and its larvae develop, and the host is the malaria-susceptible man, woman, or child. In a parallel fashion, trafficking has a host, agent, vector, and environment. The environment comprises, among other factors, poverty, socioeconomic pressures, deception, and greed. The vector is the trafficker or the chain of traffickers. The agent is the pimp, the john, and/or the sex tourist. The host is the vulnerable man, woman, or child. Nevertheless, when applied to human trafficking, such infectious disease models are simplistic and cannot fully explain the phenomenon of modern-day slavery, where there are relational dynamics, complexities, and nuances. In human trafficking, the laws of supply and demand are operative; the agents cannot be defined as one individual or a set of individuals. (The mosquito is hardly the only reason for malaria.) The signs and symptoms are not so neatly categorized as in a diseased organ system, and major and minor criteria do not define the problem as they do in traditional medicine. This is what makes the public health model both fascinating and frustrating.

To some extent, however, an infectious disease model can be applied further as we look later at the health implications of human trafficking and the appropriate interventions at various levels: individual, community, policymakers, media, and so on. As in the fight against malaria, which requires a multipronged approach to prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, combating human trafficking similarly requires such approaches. These are described as the four “P’s,” elaborated in the section on the public health approach to human trafficking.

Like infectious disease cycles, human trafficking can also be considered a process or continuum, rather than isolated steps.7 The first stage in the cycle is at the predeparture or recruitment stage. This is followed by the travel and destination/exploitation stages. Once out of the exploitation, either by escape or rescue, the person finds themselves in a reception/detention stage. Ultimately victims enter the integration/reintegration stage. Integration refers to placement at the destination; reintegration usually refers to family reunification or return to the home country. The cycle can be uneven; a person may stay in one stage for a long or short time. They may return to one stage before advancing to the next, or not advance at all. Because there are vulnerabilities at each stage, the health care professional or public health specialist should be sensitive to the complications and nuances of the trafficked person’s life and struggles. Shame and self-blame, as well as difficulty with disclosure, lack of self-respect, and mistrust of those attempting to help the trafficked person, can be significant hurdles to overcome for the victim and the health worker, child protection services personnel, and law enforcement.

Such models, however, are imperfect representations of a real-world situation. The situation can quickly become more complex when other agents and environmental conditions are operative. This is the case when the victim has family members who may be at risk or threatened by the trafficker if the victim attempts to leave one stage for the other. In other situations, the victim develops a dependency and identification relationship with their trafficker, known as the Stockholm syndrome.8 Victims may claim to, or actually be in love with their trafficker, and they may have children with him. They become dependent on their trafficker for shelter, food, and clothing and, ironically, for their relative safety. In the case of trafficked children, they may see their trafficker as a person to look up to, to trust, fear, and obey, regardless of the harm and abuse they are experiencing. In addition, trafficked persons may see themselves as responsible for their situation, or they may have normalized this abuse in their lives. Lastly, some victims “advance” from being a victim to working as a perpetrator. Having survived the abuse and learned the business, they turn to “the trade” for their own economic gain. They may recruit or manage newer victims and have a special relationship with the head trafficker.

For any public health assessment, it is important to ask what characterizes an exposure and the risks of that exposure. Risk is the probability that an event will occur, and in some occasions that event is an unfavorable outcome.9 An exposure is defined as (1) proximity and/or contact with a source of disease agent in such manner that effective transmission of the agent or harmful effects of the agent may occur, and (2) the amount of a factor to which a group or individual was exposed.10 So what constitutes risk of exposure in the world of human trafficking? And what constitutes a risk group?

The International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC) categorizes five kinds of risk factors: individual, family, external and institutional, community, and workplace.11 These risks can occur during recruitment or while looking for work or a new life. In general, individual factors include age and sex (usually young girls); being a marginalized ethnic minority with little access to services: no birth registration and lack of proof of citizenship; being an orphan or runaway; lack of education and skills; low self-esteem; innocence and naiveté, lack of awareness; and negative peer pressure. In addition, in countries or places deemed as sources or sending areas, difficulties in school leading to dropout, experience of family abuse or violence, feeling bored with village life or rural living, city attraction, and perception of a better life are also risk factors.

Family risk factors include being from a marginalized ethnic group or subservient caste; poor single parent family, or poor large family; death in a poor family; power relations within the household (usually within a patriarchal home); serious illness (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [HIV/AIDS]); domestic violence and sexual abuse; alcohol abuse and drugs in the family; past debt and bondage relations of the family; traditional attitudes and practices (sending a daughter to the extended family); and history of irregular migration and a migration network.

External and institutional risk factors include war and armed conflict; high youth unemployment; natural disasters such as floods, drought, and earthquakes; globalization and improved communication systems; strict migration controls that push movements underground; weak legal frameworks and law enforcement; corruption; weak education not relevant to labor markets; gender discrimination in education and labor; shifting social mores; and ambiguity in teen roles.

Community risk factors include location close to a border with a more prosperous country; long distance to secondary school and training centers; roads that facilitate access to large urban areas; poor quality of village leadership and community networks; lack of police, trained railway staff and border guards; lack of community entertainment; and history of migration.

Workplace risk factors include unsupervised hiring of workers, for example in border areas; poor labor protection and enforcement; unregulated informal economy and “3-D” jobs (i.e., dirty, dangerous, demanding) with poor working conditions; lack of law enforcement, labor inspection and protection; inability to change employer; sex tourism; undercover entertainment (e.g., hairdresser, massage); public tolerance of prostitution, begging, and sweatshops; and lack of organization and representation of workers.

There are also risks when in transition. Victims may travel alone rather than in a group. They may travel unprepared and uninformed and without money, or without destination address or job; they may be emotionally upset, drugged, threatened, and constrained. They may be traveling without any identification or registration, or traveling illegally. These at-risk persons may therefore be tempted to go through a nonregistered agency or smuggler or to travel at night. Once they are at their destination they may be isolated and without any social network or contact with family; they may be unable to speak the language and unable to understand the system in which they live and work; they may have illegal status; and they may be dependent on drugs and alcohol. Many or all of these risk factors may result in working in terrible conditions, which potential victims may not recognize as situations ripe for exploitation or bondage.

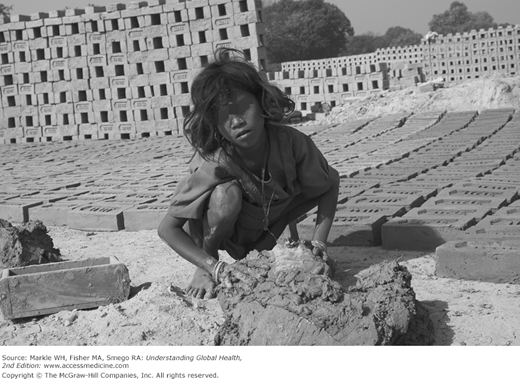

Figure 5-4.

A 9-year-old girl toils under the hot sun, making bricks from morning to night, 7 days a week. She was trafficked with her entire family from Bihar, one of the poorest and most underdeveloped states in India, and sold to the owner of a brick making factory. With no means of escape, and unable to speak the local language, the family is isolated and lives in terrible conditions. (Courtesy of Kay Chernush for the U.S. State Department. http://www.gtipphotos.state.gov.)

However, it does not take the setting of a developing country or adverse economic conditions to put someone at risk. Some seek to better their lives or that of their family by seeking employment abroad. At some point, what seemed like an opportunity for advancement becomes a situation from which they cannot escape. Passports are confiscated, debts are incurred, earnings are insufficient to retire the debt, and communication with family or friends is forbidden or impossible.

Characteristics of Trafficked Persons

Knowing these risk factors and exposures, how does the health care professional or public health specialist identify susceptible individuals or populations? One can conclude that many people around the world, as well as in your locale, are potential trafficking victims. Characteristically, these are adults (men and women) and children (boys and girls), runaway teens, so-called “throwaway kids,” marginalized populations, the displaced, the stateless, and persons caught in conflict-affected areas; and those caught in a cycle of poverty, poor education, and few vocational opportunities. The global mean age of entry into prostitution may be around 12 years of age.12

It is important to understand and appreciate the gender dimensions of trafficking. Although most think of sex trafficking when they hear the term human trafficking and therefore visualize the victim as a vulnerable woman or child, many men are trafficked victims. In studies by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) of migrant men in Belarus and Ukraine, men ages 18 to 44 years were trafficked into labor exploitation.13 Some of these men cited the need to support families and children as their decision to migrate for work. The recruitment process mimicked the legal migration process, with agreements that appeared to be legally binding with legitimate companies. On arrival, however, working conditions were clearly substandard with unheated and unhygienic living space, poor quality food, crowding, and sometimes nonpayment of wages or abuses and threats. Some migrant workers left, but not all could exit freely. When rescued from their conditions, and offered assistance, some men were not inclined to receive that help. They did not see themselves as trafficked or exploited but regarded the situation as bad luck rather than a violation of their human rights. Others saw their participation in the recruitment process as a disqualifier for assistance. Some viewed their situation as a better alternative to going home without any income at all; migration was a way to earn money, and they did not focus on the exploitative nature of the temporary work. The fact that some men either did not see themselves as trafficked victims, or even rejected that label, provides insights into providing assistance programs with gender sensitivities.

Disabilities play a role in trafficking as both a risk factor and an outcome of trafficking. Persons with disabilities are among the most at risk of being trafficked and more vulnerable to marginalization, stigmatization, and potential neglect and abuse. Health systems stretched to provide even basic services may not have the resources or advocates for care for the disabled. Disabilities include blindness, deafness, mental or physical challenges, developmental disabilities, and amputations. In some cultures, the disabled are seen as a burden on a family or community, and they risk being sold to a trafficker to unload the family of responsibility or burden. The disabled are more likely to be poorer, to be street children or beggars, or outcasts. The disabled may not be able to attend schools or are more likely to drop out, and thus they have less earning potential and fewer options, leading them to street begging, thievery, and forced prostitution. The disabled may also be more frequently perceived as virgins, less likely to be HIV positive (both conditions making them more attractive in high HIV-prevalent areas), and less likely to be able to fend off rapists or clients.

The disabled may also be disadvantaged because the loss of sight, speech, or hearing may compromise their ability to provide an understandable or credible witness and testimony against a trafficker in a court of law. Traffickers may take advantage of the disabled, thinking that the victim may be less successful in legal proceedings against them. Court systems may not be able to accommodate a disabled person in their testimony when sign language, interpreters, and physical access are not provided. Disabilities can also be the outcome of trafficking, as much as a risk. The exposure to trafficking can result in disabilities because physical and psychological abuse can be disabling. The disabilities thus engendered may cast them out of one form of trafficking and into another, continuing a vicious cycle of victimization, abuse, and helplessness.

A lesser known type of trafficked victim is the child bride. In some countries, for cultural reasons, young girls are promised to older men. Money is exchanged between the groom’s family and the bride’s family, in essence a sale of a young child or woman who may be forced to accept this new marital arrangement before the age of consent. She is not free to leave her husband and his family, may be required to work endless hours, provide sexual services to her husband, and may be resold to his friends if he has debts of his own. In Afghanistan, “opium brides”14 are the girls sold by their farming fathers to Taliban who have advanced loans to the farmer to grow poppies and produce opium. When those poppy farms fail to produce or crops are destroyed, the only way to pay the debt may be to sell a daughter to the Taliban creditors.

Characteristics of Perpetrators

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree