Human Subject Protection and Ethical Issues in Clinical Trials

It is difficult to say what truth is, but sometimes so easy to recognize a falsehood.

–Albert Einstein

Whoever is careless with truth in small matters cannot be trusted in important affairs.

–Albert Einstein

ETHICAL REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDELINES

Many national and international laws, regulations, and professional guidelines describe and protect the patient’s right to an informed consent before he or she may be given an experimental therapy or other product. Prior to 1900, the only ethical guidelines for performing experimentation on humans related to the clinicians’ need to adhere to acceptable medical standards (i.e., do no harm) in designing and conducting a clinical trial. The issue of a patient’s agreement was never formally addressed until the middle of the 20th century. It may be argued, however, that there has always been an ethical responsibility on the part of a clinician to adequately inform a patient who is to be exposed to an investigational product and to (verbally) obtain that patient’s consent.

Some of the most infamous US cases of ethical misconduct include: (a) the Tuskegee Syphilis Study run by the US government in which 400 African-American males were observed from the 1930s into the 1970s but not treated with antibiotics (e.g., penicillin) even though it was available beginning in the late 1940s [see Jones (1993) and Jenkins, Jones, and Blumenthal (2004) for additional information on this study], (b) Brooklyn Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital where live cancer cells were injected into senile patients to observe immunological responses, (c) Willowbrook study where live hepatitis virus was given to

mentally retarded children, and (d) other examples that we do or do not know about (Pence 2008).

mentally retarded children, and (d) other examples that we do or do not know about (Pence 2008).

Specific Codes, Laws, and Formal Agreements

The first major milestones in obtaining an informed consent were as follows:

The Nuremberg Code (1949), which was an outcome of World War II and the world’s outrage at Nazi experimentation and other atrocities. See Katz (1992) for the relationship of the Nuremberg Code and informed consent.

World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki was approved in 1964 and has been amended several times since then by the World Medical Association General Assembly. The history of how the Declaration of Helsinki came about is presented by Fluss (1999).

The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research from The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was issued in 1979 by the US Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. This is a modern guide for ethical issues, whose main tenants are as follows:

Respect for persons

Individuals as autonomous agents, capable of deciding about goals and actions

Informed consent is necessary to make choices

Protection for those incapable of self-determination

Beneficence

Obligation to do no harm

Obligation to maximize benefit

Justice

The benefits and risks of research should be distributed fairly (i.e., women should be allowed to enroll in clinical research trials)

Legislation in the United States was passed piecemeal by Congress for Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) (46 Federal Register 8975, January 27, 1981, 21 CFR 56) and informed consent (45 Federal Register 36390, May 30, 1980, 21 CFR 50). Several additional regulations relate to the ethical treatment of subjects in clinical trials (e.g., Financial Disclosure by Clinical Investigators). Recent laws also have had significant impact on the ethical conduct and privacy of subjects in clinical trials (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act).

The International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practices Guidelines were published in the Federal Register and are accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a required standard for clinical investigators to follow. The International Conference on Harmonisation was formed by regulators and industry associations from Europe, Japan, and the United States to develop global standards for drug development.

Internationally, the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (part of the World Health Organization, under the United Nations) passed the International Guidelines for Ethical Review of Epidemiological Studies in 1991.

Other medical and legal professional groups and organizations have created and approved various ethical standards for the conduct of clinical trials that also have had widespread impact. See the Additional Readings section for selected references.

INFORMED CONSENT

The history of informed consent has been presented by Beauchamp and Faden (2004).

Selected Issues

Over the past few decades, the issues surrounding informed consent have mushroomed and are sometimes more contentious than ever before. A few of these are mentioned to indicate the types of issues that are being discussed.

Exemption from Informed Consent

The recent plethora of issues regarding the “exemption from informed consent” is only one in a long line of difficult topics to resolve where the rights of an individual come into conflict with the rights or wishes of a much larger group that wishes to conduct clinical research in a clinical environment where the possibility of obtaining an informed consent is either impossible or nearly so. A recent example of this is the PolyHeme trial by Northfield Labs in which patients who had experienced trauma and were unable to give consent were given artificial blood without prior consent.

Providing Information to Subjects about Financial Arrangements for a Trial

Another issue in the United States is how much information should be given to the subject in an informed consent about the financial interests of the investigators, the institution, or even the IRB in the clinical trial. When it was decided to provide some information, it was originally simply to inform subjects that the investigator was being paid for each subject who enrolled in the trial, without providing any details about amounts of money or other information. In some trials, the money goes from a pharmaceutical company to the institution, and the investigator does not benefit financially, at least not directly, whereas in other trials, the investigator receives most or all of the money for the subject’s participation after expenses are paid.

Does the Informed Consent Provide for Future Use of a Subject’s Samples?

A third issue arises from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act rules that hamper the ability to obtain an informed consent after a trial is completed if blood or other samples [e.g., deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sample, pathology tissue slides, or biopsy samples] would be important to test in a future investigation. Unless all patients from the original trial can be found and agree to this subsequent analysis, some trials are unable to be undertaken. The best way to deal with this matter is to insert a phrase in the informed consent that mentions that samples that are nonidentifiable as to the patient may be studied at a later date in a genetic (or other type) of trial. This also raises the question of whether the subject or investigator will have access to the individual patient’s results from that trial, which could be of great importance to the patient.

Language Level in an Informed Consent

An informed consent document must contain language that addresses several topics (referred to as “elements”) that are laid out in the legislation covering informed consents. Examples of these documents are widely available and can be found in many places [see Spilker (1991)]. Various studies have shown that patients are generally unable to understand and retain many of the details of these forms, which often are up to 12 or more pages long. Too many of them, however, seem like legal documents and have language that would challenge a college graduate. While some computer software programs (e.g., Microsoft Word) can be used that adjust language to an appropriate grade level (about sixth or eighth grade) depending on the trial, it has been reported that IRBs have often “clarified” the one- or two-syllable words with the more “correct” term, thus obviating the benefits of using this software. It is important to note that the informed consent must be written in the language of the subjects who are asked to read and sign it.

Verbal Informed Consents

Verbal informed consents are still the norm in some countries, and in others, the investigators obtain a single signed paper that only states that the subject agrees to enroll in the trial. In the United States, a witness is only required to be present if the informed consent can only be obtained orally or is in a summary written form.

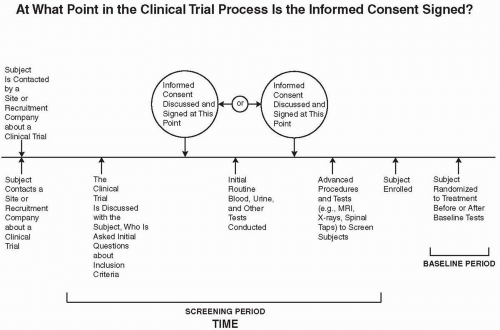

Figure 81.1 Schematic diagram of the possible times when an informed consent is to be obtained relative to three events in the screening period: initial discussion of questions to determine a subject’s possible eligibility, routine laboratory tests, and more advanced tests or procedures that involve a higher degree of risk to the subject. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

At What Point in the Screening Process Is an Informed Consent Obtained?

There are often three parts to the screening process for a subject. The first is the series of questions to determine if a subject is eligible for enrollment based on his or her responses to several or many questions about the inclusion/exclusion criteria. At that point, some or many investigators (or sponsors) want to have the subject sign an informed consent, prior to obtaining routine blood or urine samples for testing. These tests, however, do not place the subject at much risk of an adverse event, and the tests may be those that are routinely conducted for the subject as part of standard medical care.

If the subject has not signed an informed consent prior to the evaluation of routine blood and/or urine tests, then the informed consent would be signed after the results of those tests show that the subject is eligible to participate in the trial. At that point, the third set of more advanced procedures and tests to determine eligibility into the trial are conducted, if any are required beyond the routine tests performed in stage two. These tests might include a magnetic resonance imaging scan, computed tomography scan, biopsy, spinal tap, etc. Each of the tests in stages two and three may or may not be used as baseline examinations. Figure 81.1 illustrates this process and the periods when an informed consent may be obtained. Although some

regulatory professionals have told the author that it is required to obtain an informed consent prior to conducting ANY procedures that are part of screening, including routine blood tests that would be appropriate even if the patient was not being considered for a clinical trial, they have failed to show him a regulation stating that this is required. Nonetheless, the author has heard of anecdotal reports of FDA 483 citations being issued for the failure of a site to obtain an informed consent prior to obtaining routine blood tests as part of a screening procedure.)

regulatory professionals have told the author that it is required to obtain an informed consent prior to conducting ANY procedures that are part of screening, including routine blood tests that would be appropriate even if the patient was not being considered for a clinical trial, they have failed to show him a regulation stating that this is required. Nonetheless, the author has heard of anecdotal reports of FDA 483 citations being issued for the failure of a site to obtain an informed consent prior to obtaining routine blood tests as part of a screening procedure.)

Regulations do not require an informed consent to be obtained prior to conducting routine blood tests; however, for clinical trials with normal volunteers, it would be preferable to obtain the informed consent prior to obtaining blood samples, whereas for severely ill patients, it may be preferable to wait until after the results of routine blood tests are assessed. The most appropriate guide is that the informed consent should be signed prior to conducting any study-specific procedures. This means that any blood or urine tests that are not part of a study-specific procedure but are routine laboratory evaluations may be conducted prior to the signing of the informed consent.

Double Informed Consent Technique

The rule of thumb about when to obtain a subject’s informed consent to enter into a clinical trial and have him or her sign the document is prior to conducting any study-specific tests needed to evaluate subjects during the screening period. Routine laboratory tests or other tests that can be considered as part of routine care for that specific subject are able to be conducted (although definitely not required) prior to the formal informed consent process.

In some situations, it is desirable to have the patient sign the informed consent after one or more of the study-specific tests have been conducted. For example, in a highly complex open-label trial, where two groups are being compared with different procedures such as surgery, radiation, and other modalities (e.g., surgery and radiation versus drug therapy or standard of care), it would be confusing to the subject if one informed consent presented both types of treatments and this form was shown to the subject early on in the screening period and indicated to the subject that it is uncertain which treatment he would receive. This would be an opportunity to use two informed consents. Early in the screening period, one would provide a consent form only for the test(s) that are study specific and would determine eligibility for enrollment or determine which of the two treatments would be assigned to the patient. This would be a simple and short form that mentions the screening tests and indicates that a more extensive form will be given to the patient for his decision on enrolling after the results of the screening test(s) are obtained. Assuming the results of the screening tests allow the subject to enroll in the trial, the informed consent would indicate the specific treatment to be given to the subject and present the relevant information. Alternatively, a randomization process would occur, and then the subjects would be given one of two different forms to review and sign, again only discussing the treatment as it applies to them.

The advantages of this approach are to improve the subject’s understanding of the procedure and tests he will receive, minimize confusion, and (the author believes) simplify the informed consent process.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD/ETHICS COMMITTEE REVIEW OF PROTOCOLS, INVESTIGATORS’ BROCHURES, AND INFORMED CONSENTS

The IRB in the United States reviews the protocol, investigators’ brochures, informed consents, and other items such as advertisements that will be used and the money to be paid to subjects for any purpose (i.e., reimbursement for travel, food, babysitting, and participation in the trial). In the United States, the IRB must have at least five members, including at least one physician and at least one person who must be unaffiliated with the institution where the trial will be conducted. The IRB may not be composed entirely of men or women of one profession, and at least one member must be a nonscientist. Non-voting consultants may also be included. Many academic center IRBs have between 15 and 30 members, and it is not unusual for large medical schools or universities to have up to approximately five separate IRBs to handle their large workload.

IRBs may be either institutional or independent, and they may be formed on either a nonprofit or for-profit basis. Although the author was initially skeptical about whether for-profit IRBs could act without being influenced by their financial incentives, they have shown over many years that they are fully comparable to nonprofit IRBs in fulfilling their ethical responsibilities. Their primary role is to consider the ethical acceptability of the clinical trial protocols and informed consent forms. In reviewing the informed consent form, the IRB must confirm that it includes all information required by law. It may also consider the informed consent in regard to the following questions:

Does the informed consent form contain all the information that most physicians in the community would provide to their patients under similar circumstances?

Does the informed consent form contain all of the information that the patient who is considering enrollment in this clinical trial would want to know?

Is the informed consent written at a level that the patients who are likely to enroll in this trial will be able to understand?

Some IRBs request or require investigators to provide periodic updates on the trial’s progress and any information that is of particular interest to the IRB. For example, if the trial has a number of cohorts, each of which is to receive a higher dose, and questions of safety are present, then the IRB may require a report on each cohort’s data prior to allowing the next one to be initiated. This has happened for trials run by institutions and investigators who had little experience in clinical trials. If the trial has a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) that does this safety review, then the IRB may merely require a copy of their conclusion regarding the safety of each cohort.

One important point is that every IRB will decide on a protocol-by-protocol basis how proactive or not they wish to be in monitoring the progress of the trial. If the trial is a sponsored one in which the sponsor or its contract research organization (CRO) will be actively involved with monitoring, then the IRB is likely to adopt a more passive role.

Central Institutional Review Boards

A Central IRB is one that reviews a clinical trial protocol, informed consent, and investigators’ brochure for more than a single site. They may review and approve a trial’s initiation for some or all sites in a multicenter trial.

Some of the reasons that Central IRBs were developed were because of the large workload of many local IRBs that dealt with single sites, many local IRBs took a great deal of time to review a protocol, and every change suggested to the investigator had to be incorporated or discussed with the sponsor and a response given to the IRB that re-reviewed the protocol. This cycle could be repeated several times. In addition, protocol changes required by one IRB had to be approved by all of the others; whereas if a Central IRB requested changes in a protocol, the changes would be for all sites in the trial (assuming the Central IRB was reviewing the protocol for all sites). Therefore, the Central IRB concept was an attempt to improve efficiency and reduce the time needed to initiate the trial.

Central Institutional Review Board Models

There are numerous models of Central IRBs, and no single one appears best. Most are for-profit organizations, and their major advantage from the pharmaceutical company’s perspective is the rapidity with which they review protocols. This is generally because they meet more frequently than do local IRBs. Central IRBs have greater expertise in areas that most local IRBs do not, such as statistics, toxicology, and regulatory affairs.

A few of the models that are in use are as follows:

Any organization or multiple institutions may form a new IRB that serves its member institutions for selected trials. The IRB formed may be made up of members from each or only some of the institutions that will accept the findings of the IRB. An example is the Cancer and Leukemia Group B cooperative group for oncology trials. The National Cancer Institute formed an IRB a few years ago with members of selected institutions who agreed to accept the results of this IRB and conducted a pilot program to evaluate this approach.

Any organization of multiple institutions can use the IRB review of any of its members and does not form a new IRB for this purpose. An example is the Multicenter Academic Clinical Research Organization group, composed of several universities (Canfield and Schuster 2001).

Pharmaceutical companies would like to use Central IRBs more often than they do, but most institutions require their investigators to use the local IRB. Many legal and political considerations are involved, as is institutional pride. The FDA has issued guidelines for the use of Central IRBs (FDA 2006) that will hopefully increase their use.

Potential Interactions between Central and Local Institutional Review Boards

If a local IRB agreed to waive its review of its institutional investigator’s protocol and informed consent, it could receive (if desired) all reports of the clinical trial that the Central IRB would receive. These might include annual reports of the trial’s progress and status as well as all expedited Investigational New Drug Application safety reports of adverse events.

Limitations of Institutional Review Boards

Apart from members of Central IRBs, most IRBs are staffed by volunteer members, but the administration of a busy IRB is so costly that most academic nonprofit IRBs charge fees in the approximate range of $1,000 to $3,000 per protocol reviewed. The IRB members’ workload is huge, and a practice that many IRBs follow to make their workload more manageable is to assign two or three people the task of being a “lead” reviewer on a specific protocol. The lead reviewers read the protocol carefully and present their views to the entire group. This is an efficient mechanism but allows more issues to be unrecognized if others on the committee have not carefully read the protocol and informed consent.

Every IRB member should be trained to recognize content that requires input from additional reviewers. Some protocols require content area expertise that is not represented among IRB members. For example, a trial in children will require pediatricians to review the protocol, and if none are on an IRB, then it is generally a simple matter to enlist one or two to sit in the committee meetings for discussion of this protocol after the pediatrician(s) have read the protocol and related material. Expertise in regulatory affairs or toxicology or another function is often required to understand a protocol, and the IRB members may not be aware that someone with this expertise needs to be involved to assist with their review. For example, a clinical trial was conducted at Johns Hopkins University in which a ganglionic blockade agent was used in a new route of administration. The IRB‘s failure to fully appreciate this different route of administration led to the death of a healthy woman who volunteered for the clinical trial. The IRB can greatly reduce the chance that such tragedies occur by having a checklist that asks about special concerns in a protocol. An example of a checklist that an IRB can use to ensure it has considered relevant topics to review and has not overlooked items of importance was presented by Spilker (2002).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree