Human Immunodeficiency Virus Lymphadenitis

Definition

Lymphadenitis caused by infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Synonym

HIV lymphadenitis.

Epidemiology

In the 26 years since june 1981, when the first cases of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) were reported, a worldwide pandemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS has resulted in 25 million deaths and 65 million persons presently infected with HIV (1). In the united states, 1 million individuals are living with HIV infection or AIDS (2). The gravity of this situation is enhanced by a reciprocal interaction between HIV and mycobacterium tuberculosis, thus combining two severe epidemics within one large clinical population (2).

Etiology

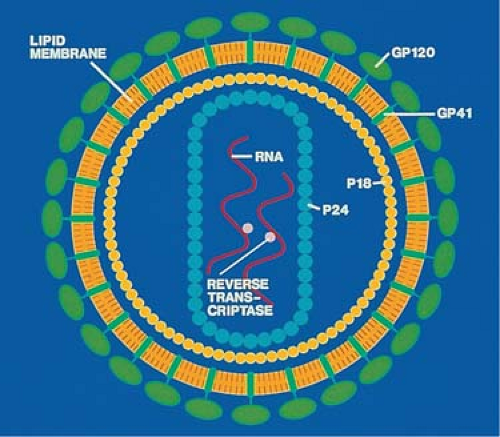

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), the etiologic agent of HIV infection, is a member of the lentiviruses, which are a subfamily of retroviruses (3). The lentiviruses cause indolent, slowly progressive infections in a variety of animals; these frequently involve the nervous system and severely affect the immune system to cause immune deficiency. Unlike most retroviruses, which have only three genes, lentiviruses have a complex genome containing multiple genes (3); HIV-1 has nine genes. It has an icosahedral structure with 72 external spikes formed by two major viral envelope glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, and a core containing four nucleocapsid proteins, p24, p17, p9, and p7 (3) (Fig. 15.1). The core also contains two copies of single-stranded RNA; associated with it are several enzymes, including the characteristic reverse transcriptase. Monoclonal antibodies to the various viral proteins have been produced and can be used to detect the virus in serum and tissue sections.

Pathogenesis

Human immunodeficiency virus manifests a strong tropism for the lymphoid tissues, particularly CD4+ T lymphocytes, monocytes, and dendritic cells. The cause of this high degree of cellular specificity is the presence on the cell membranes of CD4, of a receptor molecule to which the HIV envelope protein gp120 binds avidly (3,4,5,6,7). In the early, acute phase of HIV infection, viremia is present at high titers, and HIV infects mononuclear cells in the peripheral blood (8,9,10). Infected lymphocytes and monocytes migrate to lymphoid organs, causing acute reactive lymphadenitis. In the lymph nodes, follicular dendritic cells entrap HIV for presentation to immune T lymphocytes (11). While the infected T lymphocytes disseminate the virus, the macrophages in the circulation and the dendritic cells in the lymph nodes provide reservoirs for HIV, in which it can survive and replicate safely for long periods (12,13,14,15,16,17,18). HIV-characteristic virus particles, HIV RNA, and membrane antigens can be detected in the germinal centers of reactive infected lymph nodes (10,11,12,13,14,15,16). As a result of occult yet continuous infection, the CD4+ T lymphocytes are destroyed by cytopathic mechanisms not yet fully understood and eventually become completely depleted. Similarly, the infected dendritic cells involute, so that the follicular germinal centers disappear (17). The late phase of the HIV infection, marked by depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, involution of lymph nodes, and resurgent viremia, is the background of AIDS and its host of opportunistic infections and tumors (6).

Clinical Features

The acute phase of HIV infection generally lasts several weeks and manifests as a nonspecific, flulike syndrome that varies from almost unnoticeable symptoms to fever, sore throat, malaise, lymphadenopathies, and sometimes cutaneous rashes (19). The lymphadenopathies may persist during the following chronic phase of clinical latency, which lasts for various periods of time (median, 10 years) (7). These lymphadenopathies are indolent and involve two or more sites. The patients are usually free of other symptoms and in fairly good health. The progression of disease parallels the continuous destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes by the activity of virus released from lymphoid reservoirs (7). A drop in the CD4+ T-cell count to below 200/mm3 signals the deep immune deficiency that characterizes AIDS and favors the opportunistic infections and neoplasms of this terminal stage of the disease (6). Biopsies are frequently performed on the enlarged lymph nodes of patients with HIV lymphadenopathies, even those with known HIV serum positivity, because of the need to diagnose the many complications of AIDS that affect the lymph nodes and to institute proper treatment (16,20). A host of opportunistic agents may involve lymph nodes under the conditions of depressed immunity induced by the HIV infection. Their respective regional prevalence determines the types of lymphadenitides associated with HIV/AIDS in different parts of the world. In Africa and India, the most common lymphadenitis seen in HIV-positive persons is tuberculosis infection, whereas in the United States and Latin America, Histoplasmosis and Pneumocystosis infections are the usual complications (21,22,23). In Africa, with its >20 million HIV-infected people and having many regions with >25% of the adult population infected by tuberculosis, the association of the two diseases is strong and widespread. Peripheral lymphadenopathies, as well as abdominal lymphadenopathy, are the most common extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis in HIV/AIDS patients (22). The increasing incidence

of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in long-term AIDS survivors undergoing antiretroviral treatment is also a major reason for the biopsy and examination of enlarged lymph nodes in HIV-infected patients (24).

of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in long-term AIDS survivors undergoing antiretroviral treatment is also a major reason for the biopsy and examination of enlarged lymph nodes in HIV-infected patients (24).

Histopathology

The histopathology of HIV lymphadenitis has been considered nonspecific by some authors (25,26). In the acute phase, many of the morphologic features are indeed similar to those of other acute viral lymphadenitides. However, the histologic patterns repeatedly described by various authors are sufficiently characteristic to permit a tentative diagnosis of HIV lymphadenitis in the presence of relevant clinical and immunologic manifestations, which is confirmed subsequently by serologic testing (27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37). Three histologic patterns, A, B, and C, have been described (27,38,39,40) that generally correspond to clinical stages of acute, chronic, and burnout (7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree