KEY CONCEPTS

![]() The decision to use perimenopausal or postmenopausal hormone therapy must be individualized and based on several parameters, including menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis fracture risk, cardiovascular disease risk, breast cancer risk, and thromboembolic risk.

The decision to use perimenopausal or postmenopausal hormone therapy must be individualized and based on several parameters, including menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis fracture risk, cardiovascular disease risk, breast cancer risk, and thromboembolic risk.

![]() Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment option for alleviating vasomotor and vaginal symptoms of menopause.

Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment option for alleviating vasomotor and vaginal symptoms of menopause.

![]() Osteoporotic fracture prevention is an indication for use of systemic estrogen products when alternate therapies are contraindicated or cause adverse effects.

Osteoporotic fracture prevention is an indication for use of systemic estrogen products when alternate therapies are contraindicated or cause adverse effects.

![]() Hormone therapy may improve depressive symptoms in symptomatic menopausal women.

Hormone therapy may improve depressive symptoms in symptomatic menopausal women.

![]() Cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, is the leading cause of death among women. Postmenopausal hormone therapy should not be used for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, is the leading cause of death among women. Postmenopausal hormone therapy should not be used for reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

![]() Because of the increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer with estrogen monotherapy (i.e., unopposed estrogen), hormone therapy in women who have not undergone hysterectomy should include a progestogen in addition to the estrogen.

Because of the increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer with estrogen monotherapy (i.e., unopposed estrogen), hormone therapy in women who have not undergone hysterectomy should include a progestogen in addition to the estrogen.

![]() Use of hormone therapy at doses lower than those prescribed historically (i.e., prior to the Women’s Health Initiative study) is effective in the management of menopausal symptoms.

Use of hormone therapy at doses lower than those prescribed historically (i.e., prior to the Women’s Health Initiative study) is effective in the management of menopausal symptoms.

![]() Results from randomized trials of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women cannot be extrapolated to premenopausal women with ovarian dysfunction. Women with primary ovarian insufficiency need exogenous sex steroids to compensate for decreased production by their ovaries.

Results from randomized trials of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women cannot be extrapolated to premenopausal women with ovarian dysfunction. Women with primary ovarian insufficiency need exogenous sex steroids to compensate for decreased production by their ovaries.

MENOPAUSE AND PERIMENOPAUSAL AND POSTMENOPAUSAL HORMONE THERAPY

Epidemiology

Menopause is the permanent cessation of menses following the loss of ovarian follicular activity. The median age at the onset of menopause in the United States is 51 years. By definition, it is a physiologic event that occurs after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea, so the time of the final menses is determined retrospectively. Women who have undergone hysterectomy must rely on their symptoms to estimate the actual time of menopause.

Etiology

Menopause refers to loss of ovarian function and subsequent hormonal deficiency. This can be due to the normal process of aging (i.e., natural menopause), ovarian surgery (bilateral oophorectomy), medications (e.g., cancer chemotherapy), or pelvic irradiation.

Pathophysiology

A woman is born with approximately two million primordial follicles in her ovaries. During a normal reproductive life span, she ovulates fewer than 500 times. The vast majority of follicles undergo atresia.

The hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis dynamically controls reproductive physiology throughout the reproductive years. The pituitary is regulated by pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), produced by the pituitary in response to GnRH, regulate ovarian function. These gonadotropins also are influenced by negative feedback from estradiol and progesterone. Ovarian follicular activity is reflected by the circulating concentrations of sex steroids and by peptide hormones including inhibin, activin, and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH). AMH is a product of growing ovarian follicles, which appears to be independent of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. It is a principal regulator of early follicular recruitment from the primordial pool such that the concentration of AMH in blood may also reflect the nongrowing follicle population. AMH concentrations decline with age. For women without any menstrual cycle disorder, AMH levels predicted the median time to menopause.1 The sex steroids include estradiol, produced by the dominant follicle; progesterone, produced by the corpus luteum after maturation of the dominant ovarian follicle; and androgens, primarily testosterone and androstenedione, secreted by the ovarian stroma. Sex steroids are important for the healthy functioning of many organs, including the bones, brain, skin, and reproductive and urogenital tracts. They act primarily by regulating gene expression.

Pathophysiologic changes associated with menopause are caused by loss of ovarian follicular activity. Ovarian primordial follicle numbers decrease with advancing age, and at the time of the menopause, few follicles remain in the ovary. Hence, the postmenopausal ovary is no longer the primary site of estradiol or progesterone synthesis. The postmenopausal ovary secretes primarily androstenedione. In contrast to the acute fall in circulating estrogen at the time of menopause, the decline in circulating androgens commences in the decade leading up to the average age of natural menopause and closely parallels increasing age.2 Whether the ovary continues to secrete testosterone after menopause remains controversial.3 Hypertrophy of the ovarian stroma may develop after menopause, probably secondary to high LH concentrations, thereby resulting in increased ovarian testosterone production. Alternatively, the ovaries may become fibrotic and a poor source of sex steroids. No endocrine event clearly signals the time just prior to final menses.4

As women age, a progressive rise in circulating FSH and a concomitant decline in ovarian inhibin-B and AMH are observed. In women who continue to experience menstrual bleeding, FSH determinations on day 2 or 3 of the menstrual cycle are considered elevated when concentrations exceed 10 to 12 international units/L (10 to 12 IU/L), an indication of diminished ovarian reserve. Alternatively AMH measured at any time in the cycle predicts diminishing ovarian reserve.2 Clear elevations in serum FSH are seen in women approximately at age 40 years.4 When ovarian function has ceased, serum FSH concentrations are greater than 40 international units/L (40 IU/L). Menopause is characterized by a 10- to 15-fold increase in circulating FSH concentrations compared with concentrations of FSH in the follicular phase of the cycle, a fourfold to fivefold increase in LH, and a greater than 90% decrease in circulating estradiol concentrations.4 During the perimenopause, FSH concentrations may rise to the postmenopausal range during some cycles but return to premenopausal levels during subsequent cycles. Thus, high concentrations of FSH should not be used to diagnose menopause in perimenopausal women.

Clinical Presentation

The perimenopause commences with the onset of menstrual irregularity and ends 12 months after the last menstrual period.5 The menstrual cycle irregularity is caused by the increased frequency of anovulatory cycles. Women commonly experience symptoms during the perimenopause, which substantially impact their health and daily function. Research has shown that 25% of women experience severe vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hot flushes and night sweats), 30% experience severe psychological symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety), and 50% report moderate to severe symptoms of sleep disturbance, joint pain, or headache, and at least one in four women have sexual dysfunction.6,7

Women who experience severe symptoms, either from early in the menopause transition or from their final menstrual period, are likely to continue to experience severe symptoms for several years.6 The perimenopause is associated with a higher vulnerability to depression with the risk increasing from early to late perimenopause and decreasing during postmenopause.8 Women with a history of depression are nearly five times as likely to be diagnosed with depression during the perimenopause, whereas women with no history of depression are two to four times more likely to have a diagnosis compared with premenopausal women.8

In addition to the symptoms of menopause, loss of estrogen production results in significant metabolic changes including effects on body composition, lipids, vascular function, and bone metabolism. The menopause transition is associated with a significant increase in central abdominal fat, which may occur without commensurate change in body weight.9

Symptoms in perimenopausal women may require treatment despite the presence of menstrual bleeding. Although other conditions that may cause similar symptomatology should be first excluded, there is no condition that mimics classic menopausal vasomotor symptomatology.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding may occur during the perimenopausal years because of anovulatory cycles; however, abnormal uterine bleeding always merits investigation when it cannot be simply explained by menopausal cyclical irregularity. Treatment options for dysfunctional uterine bleeding include insertion of an intrauterine progestin-impregnated device, systemic progestogen therapy, or the combined oral contraceptive pill.

TREATMENT

Nonpharmacological options may alleviate mild symptoms but are unlikely to be effective for severely symptomatic women.

Desired Outcomes

Menopause is a natural life event, not a disease. The primary goals of therapy for menopause are to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life while minimizing adverse effects.

General Approach to Treatment

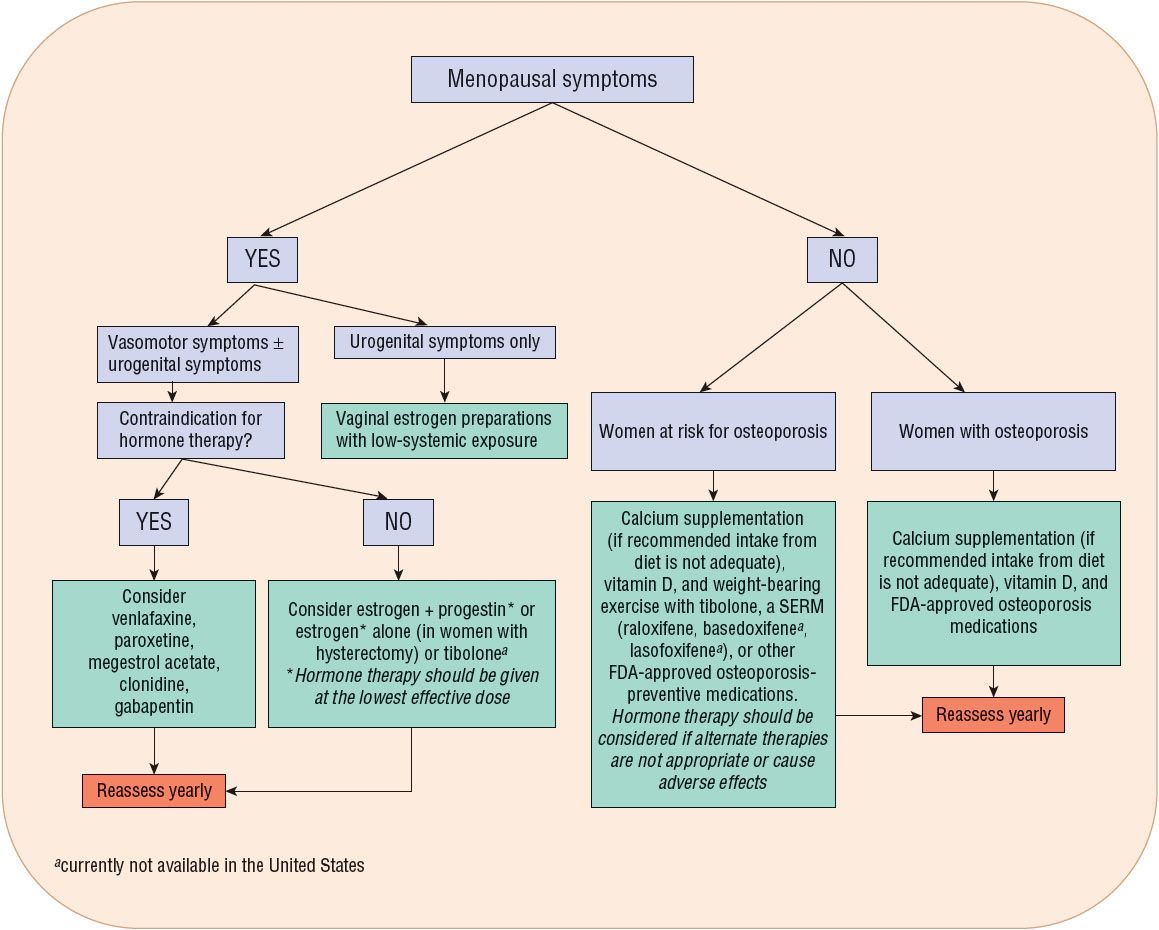

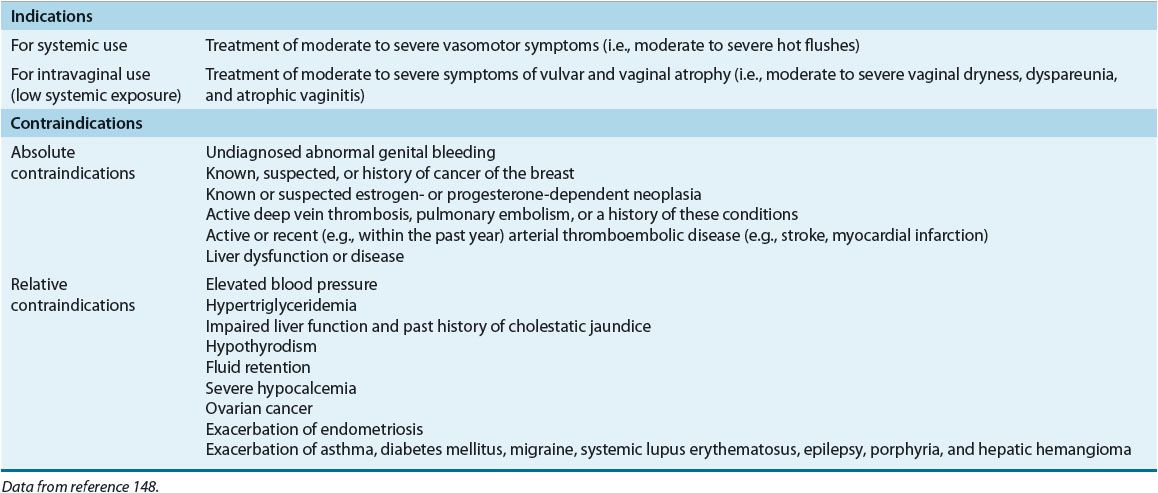

In women with mild vasomotor and/or vaginal symptoms, nonpharmacologic therapy can be considered. However, for some women these are not effective. Figure 65-1 outlines a treatment algorithm for women requiring pharmacologic therapy. In the absence of contraindications, hormone therapy is appropriate for women with hot flushes and vulvar or vaginal atrophy (Table 65-1).

FIGURE 65-1 Algorithm for pharmacologic management of menopausal symptoms.

TABLE 65-1 FDA Indications and Contraindications for Menopausal Hormone Therapy with Estrogens and Progestins

![]() The decision to use hormone therapy and the type of formulation used must be individualized and based on several parameters, including the woman’s assessment of the severity of her menopausal symptoms and her wishes, the risk of osteoporosis fracture, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and venous thromboembolic events (VTE). The potential adverse effects of hormone therapy on breast cancer and VTE risk vary according to the need for concurrent progestogen therapy and route of administration, respectively.

The decision to use hormone therapy and the type of formulation used must be individualized and based on several parameters, including the woman’s assessment of the severity of her menopausal symptoms and her wishes, the risk of osteoporosis fracture, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and venous thromboembolic events (VTE). The potential adverse effects of hormone therapy on breast cancer and VTE risk vary according to the need for concurrent progestogen therapy and route of administration, respectively.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND DIAGNOSIS Perimenopause and Menopause

The duration of therapy also needs to be individualized according to severity of symptoms and the patient’s wishes. An informed patient may choose to have longer term therapy if her symptoms are persistent. Recommendations should be specific to each woman’s clinical profile and concerns. Approved indications of hormone therapy include treatment of vasomotor symptoms and urogenital atrophy and prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. For treatment of vasomotor symptoms, systemic hormone therapy is the most effective pharmacologic intervention (see Fig. 65-1). For symptoms of urogenital atrophy, such as vaginal dryness, intravaginal products should be considered.

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Although it is frequently suggested that menopausal symptoms can be managed effectively with lifestyle modifications, including wearing layered clothing that can be removed or added as necessary, lowering room temperature, decreasing intake of hot spicy foods, caffeine, and hot beverages, exercise, and other good general health practices, most women with moderate to severe symptoms find these approaches inadequate. More recently, dietary supplements have been promoted as “complementary medicine” alternatives to hormone therapy. To date, little evidence supports the use of such nonprescription herbal products, which include various herbal remedies and soy-based supplements.

Pharmacologic Therapy

Pharmacologic therapy is the mainstay of management of menopausal symptoms and includes both hormonal (estrogen with or without progestogen) and nonhormonal medications.

Drug Treatment of First Choice

![]() Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment option for alleviating moderate and severe vasomotor and vaginal symptoms. In women with an intact uterus, hormone therapy consists of an estrogen plus a progestogen to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. In women who have undergone hysterectomy, estrogen therapy is given unopposed by a progestogen.

Hormone therapy is the most effective treatment option for alleviating moderate and severe vasomotor and vaginal symptoms. In women with an intact uterus, hormone therapy consists of an estrogen plus a progestogen to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. In women who have undergone hysterectomy, estrogen therapy is given unopposed by a progestogen.

Published Guidelines

A number of national and international guidelines and consensus statements on the management of menopause are available.10–14 The United States Preventive Services Task Force also provides a recommendation statement on the use of hormone therapy for the prevention of chronic medical conditions in postmenopausal women.15

Hormone Therapy for Vasomotor Symptoms and Vaginal Atrophy

Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for moderate and severe vasomotor symptoms, impaired sleep quality, and urogenital symptoms of menopause.

Vasomotor Symptoms The major indication for postmenopausal hormone therapy is management of vasomotor symptoms. Most women with vasomotor symptoms require hormone treatment for fewer than 5 years, so the risks of therapy appear to be small.

Fewer than 25% of women experience a menopausal transition without symptoms, whereas more than 25% suffer severe menopausal symptoms, most commonly hot flushes and night sweats. Women with mild vasomotor symptoms can experience relief by lifestyle modification, and at least 25% of women in clinical trials reported significant improvement of vasomotor symptoms when taking placebo. However, no therapy has been shown to be as effective as estrogen therapy in alleviating significant vasomotor symptoms.

Vaginal Atrophy Estrogen receptors have been demonstrated in the lower genitourinary tract, and at least 50% of postmenopausal women suffer symptoms of urogenital atrophy caused by estrogen deficiency.16 Atrophy of the vaginal mucosa results in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Lower urinary tract symptoms include urethritis, recurrent urinary tract infection, urinary urgency, and frequency. Most women with significant vaginal dryness because of vaginal atrophy require local or systemic estrogen therapy for symptom relief. Intravaginal estrogen has been shown to reduce the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections, possibly by modifying the vaginal flora.13,17 Vaginal dryness and dyspareunia can be treated with an intravaginal estrogen cream, tablet, or ring; or with the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) ospemifene. In clinical trials, vaginal estrogen appears to be better than systemic estrogen for relieving these symptoms and avoids high levels of circulating estrogen. Concomitant progestogen therapy is unnecessary if women are using low-dose micronized 17β-estradiol or estriol cream. Vaginal conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) creams are not recommended, as they require intermittent progestogen challenges (i.e., for 10 days every 12 weeks). This is an important caveat because vaginal atrophy requires long-term estrogen treatment.17

Urinary stress incontinence is not improved by estrogen therapy, whereas urge incontinence and overactive bladder, which become more prevalent with increasing age, may improve with vaginal estrogen therapy.18 Combined oral CEE and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) therapy may increase stress incontinence.19

Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment Postmenopausal osteoporosis is a serious age-related disease that affects millions of women throughout the world. Menopause is accompanied by accelerated bone loss, and the central role of estrogen deficiency in postmenopausal osteoporosis is well established. Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone mass associated with architectural deterioration of the skeleton and increased risk for fracture. Estrogen deficiency results in bone loss through its actions in accelerating bone turnover and uncoupling bone formation from resorption. It is important to recognize that bone loss commences 2 years before the final menstrual period.20 Throughout menopause, the average loss of bone mineral density (BMD) is around 6.4% at the lumbar spine and 4% to 5% at the femoral neck, with obese women experiencing less bone loss than nonobese women.20 An observational study of more than 9,000 postmenopausal women examined the relationship between endogenous estrogens and BMD, bone loss, fractures, and breast cancer.21–24 Women with detectable serum estradiol concentrations (5 to 25 pg/mL [18 to 92 pmol/L]) had a 6% to 7% higher BMD at the total hip and spine compared with women with undetectable levels (less than 5 pg/mL [18 pmol/L]).23 They also had significantly less bone loss at the hip than women with undetectable levels.22 Women with undetectable serum estradiol concentrations had a relative risk of 2.5 for subsequent hip and vertebral fractures.24 However, women with the highest estradiol serum concentrations had the greatest risk of developing breast cancer.21

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a landmark controlled clinical trial evaluating the benefits and risks of postmenopausal hormone therapy, was the first randomized trial to demonstrate that hormone therapy reduces the risk of fractures at the hip, spine, and wrist.25,26 These findings are in agreement with observational data and several meta-analyses of the efficacy of hormone therapy for reducing fractures in postmenopausal women.27 Estrogen therapy reduces bone turnover and increases bone density in postmenopausal women of all ages. The protective effect persists as long as the treatment is maintained. With cessation of therapy, postmenopausal bone loss resumes at the same rate as in untreated women.28,29 The standard bone-sparing daily estrogen dose is equivalent to 0.625 mg CEE.30 However, lower doses of estrogen have been shown to increase bone mass to the same extent as standard-dose estrogen therapy.31

![]() Systemic estrogen therapy is indicated for the prevention of osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women younger than 60 years of age who are at increased fracture risk when alternate therapies are contraindicated or cause adverse effects. Indeed estrogen is one of the few treatments shown to prevent fragility fractures in osteopenic women.

Systemic estrogen therapy is indicated for the prevention of osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal women younger than 60 years of age who are at increased fracture risk when alternate therapies are contraindicated or cause adverse effects. Indeed estrogen is one of the few treatments shown to prevent fragility fractures in osteopenic women.

General protective measures, such as regular weight-bearing exercise and avoidance of detrimental lifestyle habits such as smoking and alcohol abuse, are appropriate for all women. Some women require calcium supplementation to their dietary intake. Adequate vitamin D intake and/or supplementation is also needed. See Chapter 73 for a full discussion of osteoporosis prevention and treatment.

Colon Cancer Risk Reduction

Colorectal cancer is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States (see Chap. 107). The estrogen–progestogen arm of the WHI study showed that combined estrogen–progestogen therapy may reduce colon cancer risk.25 In the postintervention follow-up period, the reduction in colorectal cancer risk disappeared.28

Quality of Life, Mood, Cognition, and Dementia

![]() Hormone therapy improves depressive symptoms in symptomatic menopausal women, most probably by relieving flushing and improving sleep.32 Women with vasomotor symptoms receiving hormone therapy have improved mental health and fewer depressive symptoms compared with women receiving placebo; however, hormone therapy may worsen quality of life in women without flushes.33

Hormone therapy improves depressive symptoms in symptomatic menopausal women, most probably by relieving flushing and improving sleep.32 Women with vasomotor symptoms receiving hormone therapy have improved mental health and fewer depressive symptoms compared with women receiving placebo; however, hormone therapy may worsen quality of life in women without flushes.33

There is no evidence that hormone therapy improves quality of life or cognition in older, asymptomatic women.32–36

Clinical Controversy…

More than 33% of women 65 years and older will develop dementia during their lifetime.37 Several observational studies have suggested that estrogen therapy may be protective against Alzheimer’s disease (see Chap. 38). The WHI Memory Study (WHIMS, an ancillary study of the WHI trial) evaluated the effect of combined hormone therapy on dementia and cognition in 4,532 women 65 to 79 years old.35 The study found that postmenopausal women 65 years and older taking estrogen plus progestogen therapy had twice the rate of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, than women taking placebo (HR 2.05, 95% CI: 1.21 to 3.48).35 In addition, estrogen plus progestogen therapy in these women did not prevent mild cognitive impairment, a cognitive and functional state between normal aging and dementia that frequently progresses to dementia.35 The estrogen alone arm of the WHI trial showed similar findings.38,39

In contrast, the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of Younger Women (WHIMSY) found that neither estrogen plus progestogen or estrogen therapy alone confer any risk or benefit to cognitive function when taken by postmenopausal women aged 50 to 55 years old.40

Other Potential Effects

Diabetes In healthy postmenopausal women, hormone therapy appears to have a beneficial effect on fasting glucose levels in women with elevated fasting insulin concentrations.41 Also, in women with coronary artery disease, hormone therapy reduces the incidence of diabetes by 35%.42 These findings provide important insights into the metabolic effects of hormone therapy but are insufficient to recommend the long-term use of hormone therapy in women with diabetes.

Body Weight A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that unopposed estrogen or estrogen combined with a progestogen has no effect on body weight, suggesting that hormone therapy does not cause weight gain in excess of that normally observed at the time of menopause.43

Risks of Hormone Therapy

The potential risks of hormone therapy include ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, venous thromboembolism, gallbladder disease, and possibly cardiovascular disease and lung cancer in older women. The level of risk may depend on the hormonal regimen used (estrogen only vs. estrogen plus progestogen), the route of administration, dose, duration of therapy, age at treatment initiation, and the patient’s other risk factors. Data on potential risks of hormone therapy remain limited.

Cardiovascular Disease

![]() Cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, is the leading cause of death among women. Menopause is associated with the development of a more adverse lipid profile, increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease.44

Cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease, is the leading cause of death among women. Menopause is associated with the development of a more adverse lipid profile, increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease.44

In the decade prior to the publication of the WHI results in 2002, an expectation of coronary benefit had been a major reason for use of postmenopausal hormones because observational studies indicated that women who use hormone therapy have a 35% to 50% lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) than nonusers.45 In addition, previous studies have shown that estrogen exerts protective effects on the cardiovascular system, including lipid-lowering,46 antioxidant,47 and vasodilating effects.47 However, in the 2000s, published results of several randomized clinical trials provided no evidence of cardiovascular disease protection and even some evidence of harm with hormone therapy.25,48–51

The primary findings of the estrogen plus progestogen arm of the WHI trial showed an overall increase in the risk of CHD (HR 1.29, 95% CI 1.02–1.63) among healthy postmenopausal women 50 to 79 years old receiving combined estrogen–progestogen hormone therapy compared with those receiving placebo.25 The primary findings of the estrogen-only arm of the WHI trial show no effect (either increase or decrease) on the risk of coronary heart disease in women taking estrogen alone.52 Subgroup analyses performed in the years after the WHI was first published in 2002 revealed that women who initiated hormone therapy 10 or more years after the time of menopause tended to have increased CHD risk compared with women who initiated therapy within 10 years of menopause.53,54 Neither estrogen alone nor estrogen plus progestogen was associated with a statistically significant effect on CHD in women aged 50–59 years, and hormone therapy was associated with reduced overall mortality, although this decrease was not statistically significant.53 More recently, subgroup analyses from the WHI that included only adherent study participants found that the risk of CHD with estrogen plus progestogen use is increased in the first 2 years of treatment, even in women aged 50–59 years at study entry. However, the risk of CHD in women who initiated therapy within 10 years of menopause appears to decrease after 6 years of treatment.54 Most women who commence estrogen or estrogen plus progestogen therapy do so within the first few years of becoming menopausal.

A randomized controlled study of 1,006 recently menopausal women revealed that 10-year hormone therapy was associated with a significantly reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.55 In addition, studies of recently menopausal women showed that the presence and severity of hot flushes are associated with vascular endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation (markers of increased risk for CHD); hormone therapy improved both parameters.56–58 Randomized controlled studies of low-dose hormone therapy started around the time of menopause are awaited.

Clinical Controversy…

Hormone therapy should not be initiated or continued solely for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Adherence to a healthful lifestyle (cessation of smoking, regular exercise, healthy diet, and body mass index less than 25 kg/m2) may prevent the onset of cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women.

In the estrogen plus progestogen arm of the WHI study, the increased risk for stroke and venous thromboembolism continued throughout the 5 years of therapy.25 Increased risk was observed only for ischemic stroke and not for hemorrhagic stroke.59 In the estrogen-alone arm of the study, a similar increased risk for stroke was observed.52 After the cessation of treatment, there is no increased risk for stroke.28,29

Breast Cancer

The WHI trial found that combined estrogen plus progestogen oral therapy has an increased risk of invasive breast cancer (HR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.0 to 1.59) and a trend toward increasing risk with increasing duration of therapy.25 This risk does not persist after discontinuation of hormone treatment.28 The estrogen-only arm of the WHI trial found a decreased risk for breast cancer during the 7-year follow-up period,52 which persisted after discontinuation of treatment.29

In the estrogen plus progestogen arm, the increased breast cancer risk did not appear until after 3 years of study participation.25 The risk was seen only in women who initiated therapy within 5 years of the start of menopause but not in those who started therapy more than 5 years after menopause.60 The breast cancers diagnosed in women in the hormone therapy group had similar histology and grade but were more likely to be in an advanced stage compared with women in the placebo group.61 The risk of breast cancer returns to baseline rapidly after discontinuation of hormone therapy.28,62 In an unselected postmenopausal population, the Million Women Study found that current use of hormone therapy increased breast cancer risk and breast cancer mortality (relative risk 1.66 and 1.22, respectively). Increased incidence was observed for estrogen-only use (relative risk 1.30), for estrogen plus progestogen (relative risk 2), and for tibolone (relative risk 1.45).63 The risk for estrogen only and estrogen plus progestin therapy were higher for those who initiated treatment within 5 years of menopause compared to those who started therapy 5 or more years after menopause.64

For women in the United States, the lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is approximately one in eight,65 and the greatest incidence occurs in women older than 60 years (see Chap. 105). In a collaborative re-analysis of data from 51 studies evaluating 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 controls, less than 5 years of combined estrogen–progestogen therapy was associated with a 15% increase in breast cancer risk, and the risk increased with longer duration (relative risk 1.35 with 5 or more years of use).66 However, 5 years after discontinuation of hormone therapy, the risk of breast cancer was no longer increased.66

Addition of progestogens to estrogen may increase breast cancer risk beyond that observed with estrogen alone.67

Sex-steroid deficiency during the menopause results in lipomatous involution of the breast, which is seen as decreased mammographic breast density and markedly improved radiotransparency of breast tissue. Thus, mammographic changes indicating breast cancer can be recognized more easily and earlier after the menopause. Conversely, combination hormone therapy results in increased mammographic breast density, and increased density on mammography has been associated with higher breast cancer risk.68–70

Endometrial Cancer

The WHI trial suggests that combined oral hormone therapy does not increase endometrial cancer risk compared with placebo (HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.48 to 1.36).71 However, estrogen alone given to women with an intact uterus significantly increases uterine cancer risk.72 The excess risk increases with dose and duration of estrogen (10 years of unopposed estrogen increases the risk 10-fold), is apparent within 2 years of the start of treatment, and persists for many years after estrogen replacement is discontinued.72 Estrogen-induced endometrial cancer usually is of a low stage and grade at the time of diagnosis,55 and it can be prevented almost entirely by progestogen coadministration. The sequential addition of progestogen to estrogen for at least 10 days of the treatment cycle or continuous combined estrogen–progestogen does not increase the risk of endometrial cancer.73

Lower doses of estrogen may be associated with a lower risk of endometrial hyperplasia.74 SERMs do not result in endometrial hyperplasia.75 A 4-year trial of raloxifene in women with osteoporosis showed no increased risk of endometrial cancer.76

Ovarian Cancer

Lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is low (1.7%). The WHI trial suggested that orally administered combined hormone therapy does not increase the risk of ovarian cancer (HR 1.58, 95% CI: 0.77 to 3.24).71 An observational study reported an increased risk of ovarian cancer in women taking postmenopausal estrogen-only therapy for more than 10 years (relative risk 1.8, 95% CI: 1.1 to 3.0 and 3.2, 95% CI: 1.7 to 5.7 for 10 to 19 years and 20 or more years, respectively), but no increased risk of ovarian cancer among women receiving combination estrogen–progestogen therapy.77

Lung Cancer

The WHI trial found that combined oral estrogen–progestogen therapy did not increase lung cancer incidence, but significantly increased deaths from lung cancer, mainly from nonsmall cell lung cancers (HR 1.87, 95% CI: 1.22–2.88).78 The estrogen-only arm of the WHI trial found no increased risk for lung cancer death.79 It should be noted that the WHI was not designed to assess lung cancer.13

Venous Thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism, including thrombosis of the deep veins of the legs and embolism to the pulmonary arteries, is uncommon in the general population. Women taking oral estrogen therapy have a twofold increased risk for thromboembolic events, with the highest risk occurring in the first year of use.25,52 However, women with certain risk factors for venous thromboembolism including those with a Factor V Leiden mutation, obesity, and history of previous thromboembolic events, are at increased risk with hormone therapy.13 Lower doses of estrogen are associated with a decreased risk for thromboembolism as compared with higher doses.80 Oral administration of estrogen increases the risk of venous thromboembolism compared to the transdermal route.81 In addition, the norpregnane progestogens, unlike micronized progesterone, appear to be thrombogenic.

Currently, there is no indication for thrombophilia screening before initiating hormone therapy. However, hormone therapy should be avoided in women at high risk for thromboembolic events.

Gallbladder Disease

Gallbladder disease is a commonly cited complication of oral estrogen use. The WHI studies reported an increased risk for cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, and cholecystectomy among women taking oral estrogen or estrogen–progestogen therapy.82 Transdermal estrogen is an alternative to oral therapy for women at high risk for cholelithiasis.

Estrogens

Estrogens are naturally occurring hormones or synthetic steroidal or nonsteroidal compounds with estrogenic activity. The primary indication for systemic estrogen-based hormone therapy is the relief of moderate and severe vasomotor symptoms, and the initial dose should be the lowest effective dose for symptom control.

Adverse Effects Common adverse effects of estrogen include nausea, headache, breast tenderness, and heavy bleeding. More serious adverse effects include increased risk for CHD, stroke, venous thromboembolism, breast cancer, and gallbladder disease. Transdermal estradiol is associated with a lower incidence of breast tenderness and deep vein thrombosis than is oral estrogen.55,83,84

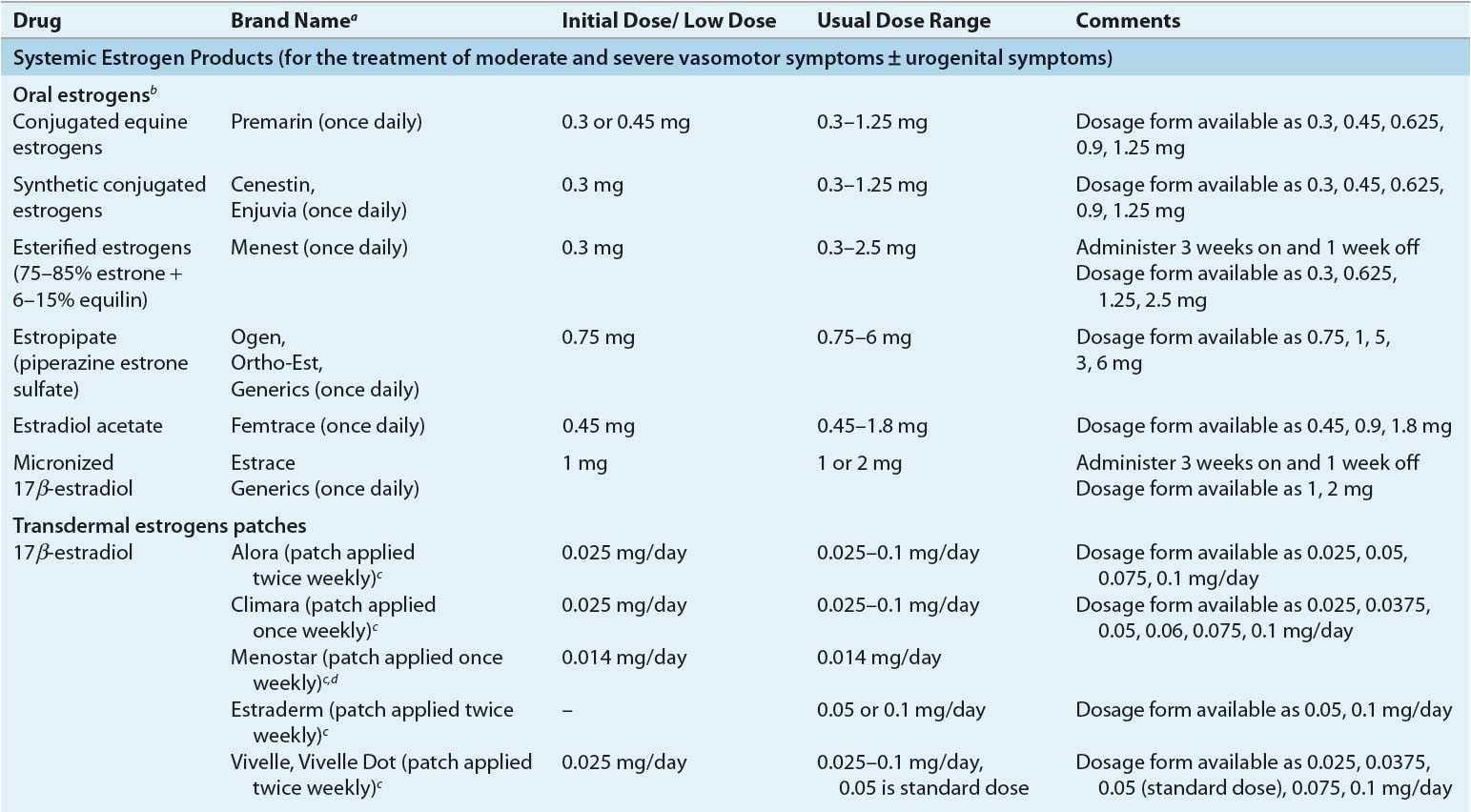

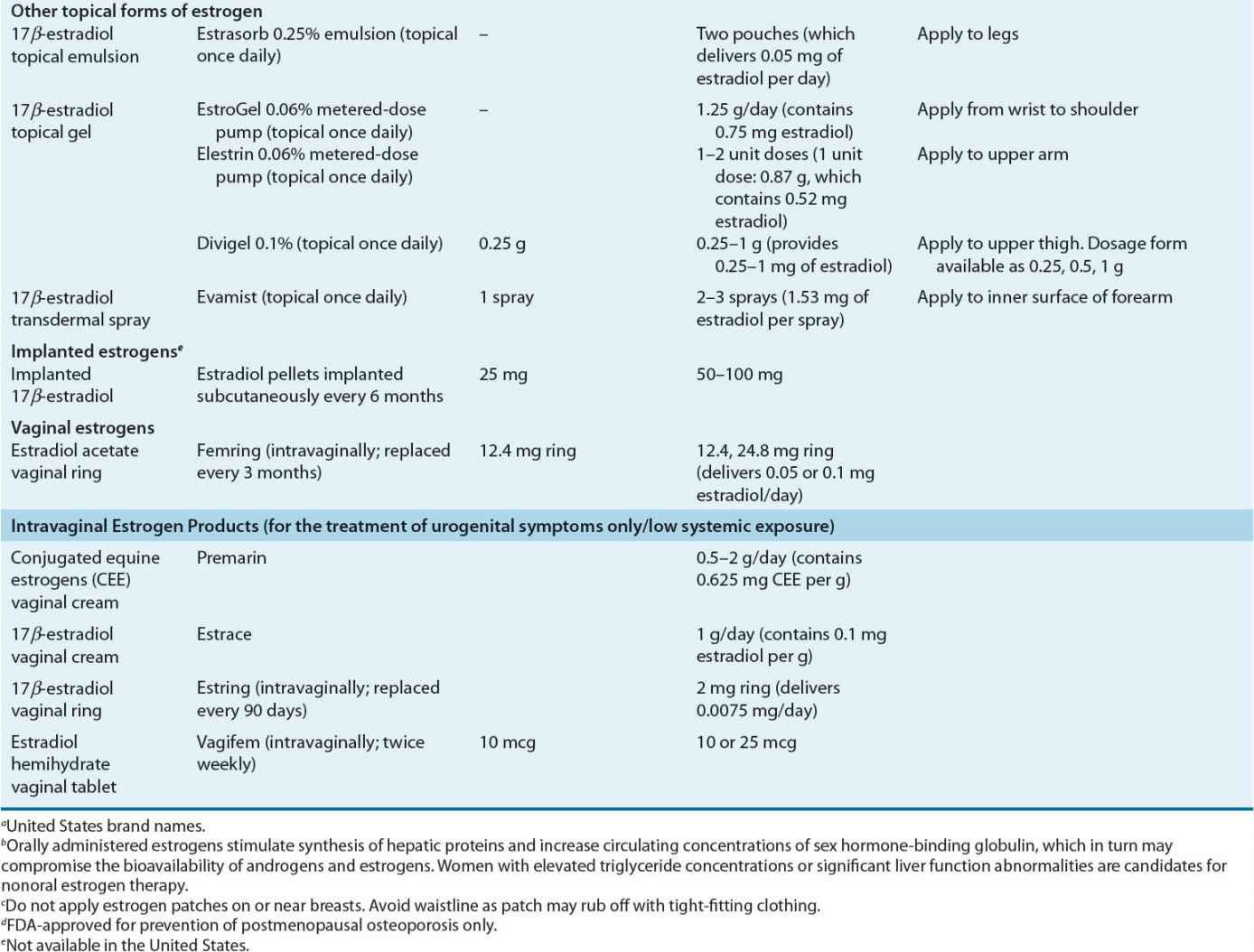

Dose and Administration Various systemically administered estrogens (typically oral and transdermal) are suitable for replacement therapy (Table 65-2). Estrogens can be administered orally, percutaneously (transdermal patches and topical products), intravaginally (creams, tablets, or rings), intramuscularly, and even subcutaneously in the form of implanted pellets. The choice of estrogen delivery (product, route, and method) should be determined in consultation with the patient to ensure acceptability and enhance adherence. In general, the oral and transdermal routes are used most frequently. No evidence indicates that one estrogen compound is more effective than another in relieving menopausal symptoms or preventing osteoporosis.

TABLE 65-2 Estrogen Products for Hormone Therapy

Oral Estrogen Oral CEE has been available for more than 50 years. CEE is prepared from the urine of pregnant mares and is composed of estrone sulfate (50% to 60%) and multiple other equine estrogens such as equilin and 17α-dihydroequilin.85

Estradiol is the predominant and most active form of endogenous estrogens. A micronized form of estradiol (produced by a technique that yields extremely small particles of the pure hormone) is readily absorbed from the small intestines.85 When given orally, estradiol is metabolized by the intestinal mucosa and the liver during the first hepatic passage, and only 10% reaches circulation as free estradiol. Metabolism of estrogen is partly mediated by the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme. Gut and liver metabolism converts a large proportion of estradiol to the less potent estrone. Thus, measurement of serum estradiol is not useful for monitoring oral estrogen replacement. The principal metabolites of micronized estradiol are estrone and estrone sulfate. Administration of estradiol via the oral route results in estrone concentrations that are three to six times those of estradiol. Ethinyl estradiol is a highly potent semisynthetic estrogen that has similar activity following administration by the oral or nonoral route.

Orally administered estrogens stimulate the synthesis of hepatic proteins and increase the circulating concentrations of sex hormone-binding globulin, which, in turn, may compromise the bioavailability of androgens and estrogens.

Other Routes Nonoral forms of estrogens bypass the GI tract and thereby avoid first-pass liver metabolism. These routes of estradiol delivery result in a more physiologic estradiol-to-estrone ratio (estradiol concentrations greater than estrone concentrations), as seen in the normal premenopausal state. Transdermal estrogen therapy also is less likely to affect sex hormone-binding globulin compared with oral therapy. These regimens produce little or no change in circulating lipids, coagulation parameters, or C-reactive protein levels.86

Transdermal estrogen patches share the advantages of other nonoral estrogen routes and have the added advantage of delivering estradiol to the general venous circulation at a continuous rate. The matrix transdermal systems (estrogen in adhesive) generally are well tolerated, and fewer than 5% of women experience skin reactions.87 The incidence of skin irritation diminishes when the application site is rotated. Topical antiinflammatory products (e.g., hydrocortisone cream) can be applied for managing the rashes, and switching to another transdermal patch is often a viable option.

Topical gels, sprays, and emulsions are convenient, but variability in drug absorption has been noted with some formulations. These forms of estrogen are also used for systemic therapy.

Estradiol pellets (implants) containing pure crystalline 17β-estradiol have been available for more than 50 years. They are inserted subcutaneously into the anterior abdominal wall or buttock. Pellets are difficult to remove and may continue to release estradiol for a long time after insertion. Implantation should not be repeated until serum estradiol concentrations have fallen to values similar to those at the midfollicular phase of the menstrual cycle. Estradiol pellets are not available in the United States.

Intravaginal creams, tablets, and rings are used for treatment of urogenital (vulvar and vaginal) atrophy. However, this route of administration can have more than just a local effect. Systemic estrogen absorption is lower with vaginal tablets and rings (specifically Estring) compared with vaginal creams. Nonetheless, local application of the cream at low doses can reverse atrophic vaginal changes and avoid significant systemic exposure. Nonestrogen vaginal moisturizers and lubricants also may provide local symptom relief. These products can be used alone or in combination with locally acting intravaginal estrogens. Intravaginal rings are a sustained-release delivery system composed of a biologically inert liquid polymer matrix with pure crystalline estradiol that can maintain adequate estradiol concentrations. One such intravaginal ring product (Femring) is designed to achieve systemic concentrations of estrogen and is indicated for treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms.

Progestogens

![]() Because of the increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer with estrogen monotherapy (unopposed estrogen), women who have not undergone hysterectomy should be treated concurrently with a progestogen in addition to the estrogen.88

Because of the increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer with estrogen monotherapy (unopposed estrogen), women who have not undergone hysterectomy should be treated concurrently with a progestogen in addition to the estrogen.88

Progestogens reduce nuclear estradiol receptor concentrations, suppress DNA synthesis, and decrease estrogen bioavailability by increasing the activity of endometrial 17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, an enzyme responsible for converting estradiol to estrone.72

The first generation of progestogens included the C-19 androgenic progestogens norethindrone (also known as norethisterone), norgestrel, and levonorgestrel. More recent preparations have included the C-21 progestogens dydrogesterone and MPA, which are less androgenic. Drospirenone, a synthetic progestogen analog of the potassium-sparing diuretic spironolactone, has both antiandrogenic and antialdosterone properties. Micronized progesterone also has become available for use in postmenopausal women. The most commonly used oral progestogens are MPA, micronized progesterone, and norethindrone acetate. The latter can be administered transdermally in the form of a combined estrogen–progestogen patch.

Adverse Effects Common adverse effects of progestogens include irritability, weight gain, bloating, and headache. Changing from a cyclic to a continuous-combined regimen or changing from one progestogen to another may decrease the incidence or severity of untoward effects. Adverse effects of progestogens are difficult to evaluate and can vary with the agent administered. Some women experience “premenstrual-like” symptoms, such as mood swings, bloating, fluid retention, and sleep disturbance. Newer methods and routes of progestogen delivery (e.g., locally by an intrauterine device that releases levonorgestrel or a progesterone-containing bioadhesive vaginal gel) may be associated with fewer adverse effects.

Dose and Administration Several progestogen regimens designed to prevent endometrial hyperplasia are available (Table 65-3). Progestogens must be taken for a sufficient period of time during each cycle. A minimum of 12 to 14 days of progestogen therapy each month is required for complete protection against estrogen-induced endometrial hyperplasia.89 Of note, use of even low-dose estrogen, including some intravaginal preparations, requires progestogen coadministration for endometrial protection in women with an intact uterus.90 However, rarely is progestogen administration needed in women who have undergone hysterectomy (i.e., women with hysterectomy and a past history of endometriosis).

TABLE 65-3 Progestogen Doses for Endometrial Protection (Oral Cyclic Administration)