High Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction

Eduardo De Santibañes

Victoria Ardiles

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an uncommon gastrointestinal malignancy that has a bleak prognosis. Although similar tumors had been described 1957 by Altemeier et al., it was Gerald Klatskin in 1965 who defined their particular characteristics. So hilar CCA is today known universally as “Klatskin tumor.”

Since 1974, when wide resection was shown to improve survival for hilar CCA, surgeons have pushed the technical envelope to achieve negative margins. Today, extended biliary–hepatic resections together with vascular resections/reconstructions are being performed. Survival rates, however, have still not exceeded 40%.

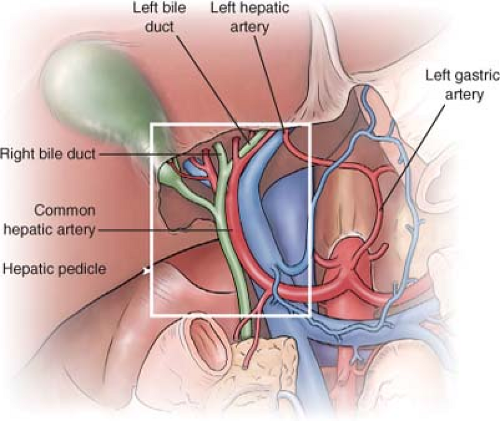

Some anatomical features with particular implications in the management of hilar CCA are as given (Fig. 1):

In the hepatic hilum, division of left hepatic duct occurs more distally, being longer than the right duct (2-5 cm vs. 1 cm) and having a greater extrahepatic portion.

There is a close relation between vascular and biliary structures (especially the right hepatic artery that runs behind the bile duct), promoting early vascular invasion in these tumors.

With a frequency of 15%, the left hepatic artery arises directly from the left gastric artery and left up to the liver by the gastrohepatic ligament. This variation allows more extensive dissection of the porta hepatis without compromising the arterial supply of the left lobe.

In 13% of cases, the right hepatic artery arises directly from the superior mesenteric artery, and goes up through the right posterolateral aspect of the portal vein. This variation may cause the dissection of the pedicle to be technically demanding, and produce a longer distance between the artery and the biliary tree, increasing resectability.

Hilar CCA is usually symptomatic and when the tumor obstructs the biliary drainage system, can produce painless jaundice. Other symptoms that may be present, although less frequent, include pruritus, weight loss, abdominal pain, fatigue, fever, nausea, and vomiting. In 50% of cases there are regional lymph nodes metastases at diagnosis. Peritoneal and liver metastases are early and frequent, and distant metastases are rare.

The serum liver function tests in patients with hilar CCA commonly demonstrate obstructive jaundice with alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin levels elevated more than 95% and 85% of patients, respectively. But liver biochemical tests are rarely used to differentiate between benign or other malignancies that present cholestasis.

Elevation of CA19.9 helps in the diagnosis of hilar CCA but is not specific. In patients without cholestasis or cholangitis, a

CA 19.9>37 U/mL has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 63% for detecting malignant biliary disease. By contrast, in the presence of cholangitis or cholestasis, the cutoff value to avoid losing specificity is 300U/mL, sacrificing the sensitivity that drops to 41%. That is why the dosage of CA 19.9 can help in diagnosis, but we use it mainly to monitor the effect of treatment or detect recurrence of disease.

CA 19.9>37 U/mL has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 63% for detecting malignant biliary disease. By contrast, in the presence of cholangitis or cholestasis, the cutoff value to avoid losing specificity is 300U/mL, sacrificing the sensitivity that drops to 41%. That is why the dosage of CA 19.9 can help in diagnosis, but we use it mainly to monitor the effect of treatment or detect recurrence of disease.

Diagnosis of a hilar CCA can be challenging and is often suggested by indirect signs of the presence of tumor, like intrahepatic bile duct dilatation with normal main bile duct and amputation of biliary confluence.

Often abdominal ultrasound is used as the first diagnostic study to confirm biliary ductal dilatation, identify the level of obstruction, and exclude gallstones. However, a quarter of patients with jaundice and biliary stricture on ultrasound images have benign lesions or other malignancies obstructing the hepatic confluence including cancer of the gallbladder or hilar lymph node metastases.

Fig. 1. Anatomical features with particular implications in the management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. |

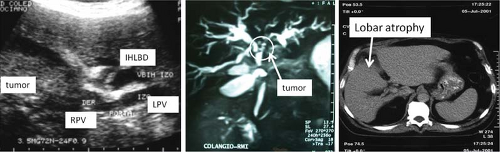

Fig. 2. Hepatic ultrasound, cholangio magnetic resonance imaging and abdominal computed tomography. RPV: right portal vein; LPV: left portal vein; IHLBD: intrahepatic left bile duct. |

To perform differential diagnosis with other pathologies, we usually complete the patient study with a multislice computed tomography (CT) scan and a cholangio magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although some authors prefer to perform one or the other, we believe that both provide information that helps us to assess tumor resectability more accurately (Fig. 2).

To evaluate the resectability and tumor expansion we must consider biliary extension, portal and arterial involvement, lymph node status, distant metastases, lobar atrophy, and function and volume of remnant liver.

Rapid-sequence, thin-section, helical CT allows the evaluation of intrahepatic ductal dilatation, portal vein pathology, hilar lymph node involvement, hepatic invasion, and lobar atrophy, which is an indirect sign of vascular compromise. It can also be used to screen for extrahepatic disease and to make measurements of total liver volume and future remnant liver.

MRI with cholangiopancreatography provides a three-dimensional image of the biliary tree by sensitivity comparable with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTHC). This is a noninvasive study, and therefore there is no risk of cholangitis associated with the procedure and does not require the drainage or the biliary tree poststudy.

ERCP and PTHC are invasive studies that provide dynamic imaging of the biliary system. One limitation is that in cases of complete obstruction of the bile duct, ERCP cannot evaluate the proximal biliary tree and PTHC cannot evaluate the distal bile duct. Also, after these procedures it is necessary to drain the biliary tree in order to avoid biliary sepsis that changes the entire management and limits flexibility.

Staging

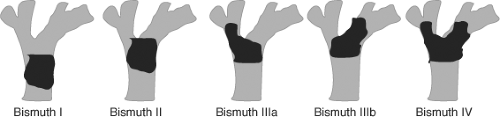

In 1975, Bismuth and Corlette proposed a clinical classification based on anatomical location of the tumor. While this classification is useful for determining the tumor location and biliary extension, it is not predictive of respectability (Fig. 3).

In 2001, Jarnagin and colleagues proposed a staging system that takes into account not only the extent and location in the biliary tree but also the arterial and portal vascular invasion and lobar atrophy, irrespective of

nodal stage. This staging of Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center for hilar CCA is correlated with resectability and survival. So, 59% of stage T1 tumors were resectable with a median survival of 20 months; however, resectability in T3 stages were 0% and median survival was only 8 months.

nodal stage. This staging of Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center for hilar CCA is correlated with resectability and survival. So, 59% of stage T1 tumors were resectable with a median survival of 20 months; however, resectability in T3 stages were 0% and median survival was only 8 months.

Surgical resection is the suitable treatment for patients with hilar CCA. The 5-year survival of patients resected with curative intent is 10% to 44% versus 0% to 3% of those who could not be resected or were palliated. But because of the anatomical relationships and dissemination characteristics of this tumor, only 30% of patients are candidates for surgical resection. Currently, however, due to the possibility of in-bloc resection and vascular reconstruction techniques, the resection rate has increased significantly. Thus, the arterial and portal vascular invasion is no longer a contraindication to explore these patients. The same applies to the lymph nodes in areas 1 and 2 detected on preoperative imaging studies.

Radiographic criteria that suggest local unresectability of perihilar tumors include bilateral hepatic duct involvement up to secondary radicles, encasement or occlusion of the main portal vein proximal to its bifurcation, atrophy of one liver lobe with encasement of the contralateral portal vein branch, atrophy of one liver lobe with contralateral secondary biliary radicle involvement, involvement of bilateral hepatic arteries. Tumor invasion to adjacent organs, disseminated disease, and lymph node metastases other than in areas 1 and 2 remain criteria for unresectability. However, as a general rule, true resectability is ultimately determined at surgery.

Preoperative Biliary Drainage

The incidence of postoperative liver failure and postoperative morbidity rates are higher in patients with obstructive jaundice. However, the role of preoperative biliary drainage in these patients is controversial. Among the potential benefits are the treatment of preexisting cholangitis and restoration of function and capacity of liver regeneration. However, preoperative biliary drainage can have complications related to the procedure and is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative infections, longer hospitalization, and risk of tumor seeding along the catheter track.

Based on current evidence, we recommend that preoperative biliary drainage should be done selectively in patients with cholangitis, malnutrition, sepsis, after portal embolization, when surgery should be deferred, and after invasive diagnostic procedures with contrast injection in the bile duct.

Preoperative Portal Embolization

This procedure, which can be performed percutaneously or by laparotomy, occludes the portal branches feeding the hepatic segments schedule for resection, producing atrophy of this area and compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral liver parenchyma (not embolized). It is indicated when the theoretical remnant liver is less than 25% to 30% in healthy livers (without cholestasis or cholangitis that are usual in these patients). Preoperative portal embolization minimizes the abrupt increase of portal pressure after resection that can lead to liver failure in the remnant liver, increases liver mass before resection, reducing the risk of metabolic insufficiency, and dissociates in time portal hypertension from cellular damage caused by the trauma of mobilization at the time of surgery of the remnant liver.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree