I. HERNIAS

An external hernia is an abnormal protrusion of intra-abdominal tissue through a fascial defect in the abdominal wall.* Although most hernias (75%) occur in the groin, incisional hernias represent an increasing proportion (15%-20%), with umbilical and other ventral hernias comprising the remainder. Generally, a hernial mass is composed of covering tissues (skin, subcutaneous tissues, etc), a peritoneal sac, and any contained viscera. Particularly if the neck of the sac is narrow where it emerges from the abdomen, bowel protruding into the hernia may become obstructed or strangulated. If the hernia is not repaired early, the defect may enlarge and operative repair may become more complicated. The definitive treatment of hernia is operative repair.

A reducible hernia is one in which the contents of the sac return to the abdomen spontaneously or with manual pressure when the patient is recumbent.

An irreducible (incarcerated) hernia is one whose contents cannot be returned to the abdomen, usually because they are trapped by a narrow neck. The term “incarceration” does not imply obstruction, inflammation, or ischemia of the herniated organs, though incarceration is necessary for obstruction or strangulation to occur.

Though the lumen of a segment of bowel within the hernia sac may become obstructed, there may initially be no interference with blood supply. Compromise to the blood supply of the contents of the sac (eg, omentum or intestine) results in a strangulated hernia, in which gangrene of the contents of the sac has occurred. The incidence of strangulation is higher in femoral than in inguinal hernias, but strangulation may occur in any hernia.

An uncommon and dangerous type of hernia, a Richter hernia, occurs when only part of the circumference of the bowel becomes incarcerated or strangulated in the fascial defect. A strangulated Richter hernia may spontaneously reduce and the gangrenous piece of intestine be overlooked at operation. The bowel may subsequently perforate, with resultant peritonitis.

All groin hernias protrude through the myopectineal orifice of Fruchaud, a weakness or defect in the transversalis fascia, an aponeurosis located just outside the peritoneum. External to the transversalis fascia are found the transversus abdominis, internal oblique, and external oblique muscles, which are fleshy laterally and aponeurotic medially. Their aponeuroses form investing layers of the strong rectus abdominis muscles above the semilunar line. Below this line, the aponeurosis lies entirely in front of the muscle. Between the two vertical rectus muscles, the aponeuroses meet again to form the linea alba, which is well defined only above the umbilicus. The subcutaneous fat contains the Scarpa fascia—a misnomer, since it is only a condensation of connective tissue with no substantial strength.

In the groin, an indirect inguinal hernia results when obliteration of the processus vaginalis, the peritoneal extension accompanying the testis in its descent into the scrotum, fails to occur. The resultant hernia sac passes through the internal inguinal ring, a defect in the transversalis fascia halfway between the anterior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle. The sac is located anteromedially within the spermatic cord and may extend partway along the inguinal canal or accompany the cord out through the subcutaneous (external) inguinal ring, a defect medially in the external oblique muscle just above the pubic tubercle. A hernia that passes fully into the scrotum is known as a complete hernia. The sac and the spermatic cord are invested by the cremaster muscle, an extension of fibers of the internal oblique muscle.

Other anatomic structures of the groin that are important in understanding the formation of hernias and types of hernia repairs include the conjoined tendon, a fusion of the medial aponeurotic transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles that passes along the inferolateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle and attaches to the pubic tubercle. Between the pubic tubercle and the anterior iliac spine passes the inguinal (Poupart) ligament, formed by the lowermost border of the external oblique aponeurosis as it rolls on itself and thickens into a cord.

Just deep and parallel to the inguinal ligament runs the iliopubic tract, a band of connective tissue that extends from the iliopsoas fascia, crosses below the deep inguinal ring, forms the superior border of the femoral sheath, and inserts into the superior pubic ramus to form the lacunar (Gimbernat) ligament. The lacunar ligament is about 1.25 cm long and triangular in shape. The sharp, crescentic lateral border of this ligament is the unyielding noose for the strangulation of a femoral hernia.

The Cooper ligament is a strong, fibrous band that extends laterally for about 2.5 cm along the iliopectineal line on the superior aspect of the superior pubic ramus, starting at the lateral base of the lacunar ligament.

The Hesselbach triangle is bounded by the inguinal ligament, the inferior epigastric vessels, and the lateral border of the rectus muscle. A weakness or defect in the transversalis fascia, which forms the floor of this triangle, results in a direct inguinal hernia. In most direct hernias, the transversalis fascia is diffusely attenuated, though a discrete defect in the fascia may occasionally occur. This funicular type of direct inguinal hernia is more likely to become incarcerated, since it has distinct borders.

A femoral hernia passes beneath the iliopubic tract and inguinal ligament into the upper thigh. The predisposing anatomic feature for femoral hernias is a small empty space between the lacunar ligament medially and the femoral vein laterally—the femoral canal. Because its borders are distinct and unyielding, a femoral hernia has the highest risk of incarceration and strangulation of groin hernias.

Surgeons must be familiar with the pathways of the nerves and blood vessels of the inguinal region to avoid injuring them when repairing groin hernias. The iliohypogastric nerve (T12, L1) emerges from the lateral edge of the psoas muscle and travels inside the external oblique muscle, emerging medial to the external inguinal ring to innervate the suprapubic skin. The ilioinguinal nerve (L1) parallels the iliohypogastric nerve and travels on the surface of the spermatic cord to innervate the base of the penis (or mons pubis), the scrotum (or labia majora), and the medial thigh. This nerve is the most frequently injured in anterior open inguinal hernia repairs. The genitofemoral (L1, L2) and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves (L2, L3) travel on and lateral to the psoas muscle and provide sensation to the scrotum and anteromedial thigh and to the lateral thigh, respectively. These nerves are subject to injury during laparoscopic hernia repairs. The femoral nerve (L2-L4) travels from the lateral edge of the psoas and extends lateral to the femoral vessels. It can be injured during laparoscopic or femoral hernia repairs.

The external iliac artery travels along the medial aspect of the psoas muscle and beneath the inguinal ligament, giving off the inferior epigastric artery, which borders the medial aspect of the internal inguinal ring. The corresponding veins accompany the arteries. These vessels can be injured during hernia repairs of all types.

*See Chapter 43 for further discussion of hernias in the pediatric age group and Chapter 21 for a discussion of internal hernias.

Nearly all inguinal hernias in infants, children, and young adults are indirect inguinal hernias. Although these “congenital” hernias most often present during the first year of life, the first clinical evidence of hernia may not appear until middle or old age, when increased intra-abdominal pressure and dilation of the internal inguinal ring allow abdominal contents to enter the previously empty peritoneal diverticulum. An untreated indirect hernia will inevitably dilate the internal ring and displace or attenuate the inguinal floor. The peritoneum may protrude on either side of the inferior epigastric vessels to give a combined direct and indirect hernia, called a pantaloon hernia.

In contrast, direct inguinal hernias are acquired as the result of a developed weakness of the transversalis fascia in the Hesselbach area. There is some evidence that direct inguinal hernias may be related to hereditary or acquired defects in collagen synthesis or turnover. Femoral hernias involve an acquired protrusion of a peritoneal sac through the femoral ring. In women, the ring may become dilated by physical and biochemical changes during pregnancy.

Any condition that chronically increases intra-abdominal pressure may contribute to the appearance and progression of a hernia. Marked obesity, abdominal strain from heavy exercise or lifting, cough, constipation with straining at stool, and prostatism with straining on micturition are often implicated. Cirrhosis with ascites, pregnancy, chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, and chronically enlarged pelvic organs or pelvic tumors may also contribute. Loss of tissue turgor in the Hesselbach area, associated with a weakening of the transversalis fascia, occurs with advancing age and in chronic debilitating disease.

Most hernias produce no symptoms until the patient notices a lump or swelling in the groin, though some patients may describe a sudden pain and bulge that occurred while lifting or straining. Frequently, hernias are detected in the course of routine physical examinations such as preemployment examinations. Some patients complain of a dragging sensation and, particularly with indirect inguinal hernias, radiation of pain into the scrotum. As a hernia enlarges, it is likely to produce a sense of discomfort or aching pain, and the patient must lie down to reduce the hernia.

In general, direct hernias produce fewer symptoms than indirect inguinal hernias and are less likely to become incarcerated or strangulated.

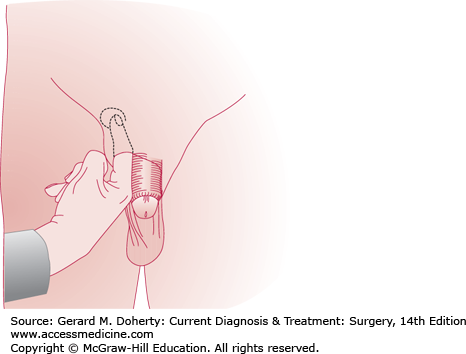

Examination of the groin reveals a mass that may or may not be reducible. The patient should be examined both supine and standing and also with coughing and straining, since small hernias may be difficult to demonstrate. The external ring can be identified by invaginating the scrotum and palpating with the index finger just above and lateral to the pubic tubercle (Figure 32–1). If the external ring is very small, the examiner’s finger may not enter the inguinal canal, and it may be difficult to be sure that a pulsation felt on coughing is truly a hernia. At the other extreme, a widely patent external ring does not by itself constitute hernia. Tissue must be felt protruding into the inguinal canal during coughing in order for a hernia to be diagnosed.

Differentiating between direct and indirect inguinal hernia on examination is difficult and is of little importance, since most groin hernias should be repaired regardless of type. Nevertheless, each type of inguinal hernia has specific features more common to it. A hernia that descends into the scrotum is almost certainly indirect. On inspection with the patient erect and straining, a direct hernia more commonly appears as a symmetric, circular swelling at the external ring; the swelling disappears when the patient lies down. An indirect hernia appears as an elliptic swelling that may not reduce easily.

On palpation, the posterior wall of the inguinal canal is firm and resistant in an indirect hernia but relaxed or absent in a direct hernia. If the patient is asked to cough or strain while the examining finger is directed laterally and upward into the inguinal canal, a direct hernia protrudes against the side of the finger, whereas an indirect hernia is felt at the tip of the finger.

Compression over the internal ring when the patient strains may also help to differentiate between indirect and direct hernias. A direct hernia bulges forward through Hesselbach triangle, but the opposite hand can maintain reduction of an indirect hernia at the internal ring.

These distinctions are obscured as a hernia enlarges and distorts the anatomic relationships of the inguinal rings and canal. In most patients, the type of inguinal hernia cannot be established accurately before surgery.

Groin pain of musculoskeletal or obscure origin occurs primarily with vigorous physical exertion (so-called “sports hernia”) and may be difficult to distinguish from a true hernia, even with thorough physical examination. MRI may be helpful in identifying the problem as inflammation, edema, or a muscle or tendon tear or strain.

Herniation of preperitoneal fat through the inguinal ring into the spermatic cord (lipoma of the cord) is commonly misinterpreted as a hernia sac. Its true nature may only be confirmed at operation. Occasionally, a femoral hernia that has extended above the inguinal ligament after passing through the fossa ovalis femoris may be confused with an inguinal hernia. If the examining finger is placed on the pubic tubercle, the neck of the sac of a femoral hernia lies lateral and below, while that of an inguinal hernia lies above.

Inguinal hernia must be differentiated from hydrocele of the spermatic cord, lymphadenopathy or abscesses of the groin, varicocele, and residual hematoma following trauma or spontaneous hemorrhage in patients taking anticoagulants. An undescended testis in the inguinal canal must also be considered when the testis cannot be felt in the scrotum.

The presence of an impulse in the mass with coughing, bowel sounds in the mass, and failure to transilluminate are features that indicate that an irreducible mass in the groin is a hernia.

Although inguinal hernias have traditionally been repaired electively to avoid the risks of incarceration, obstruction, and strangulation, asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic hernias may be safely observed in elderly, sedentary patients or those with high morbidity for operation. The annual risk of hernia incarceration is not precisely known but has been estimated at fewer than 2/1000 patients per year. However, a high percentage of patients become symptomatic while being observed expectantly. All symptomatic groin hernias should be repaired if the patient can tolerate surgery.

Even elderly patients tolerate elective repair of a groin hernia very well when other medical problems are optimally controlled and local anesthetic is used. Emergency operation carries a much greater risk for the elderly than carefully planned elective operation.

If the patient has significant prostatic hyperplasia, it is prudent to solve this problem first, since the risks of urinary retention and urinary tract infection are high following hernia repair in patients with significant prostatic obstruction.

Although most direct hernias do not carry as high a risk of incarceration as indirect hernias, the difficulty in reliably differentiating them from indirect hernias makes the repair of all symptomatic inguinal hernias advisable. Direct hernias of the funicular type, which are particularly likely to incarcerate, should always be repaired.

Because of the possibility of strangulation, an incarcerated, painful, or tender hernia usually requires an emergency operation. Nonoperative reduction of an incarcerated hernia may first be attempted. The patient is placed with hips elevated and given analgesics and sedation sufficient to promote muscle relaxation. Repair of the hernia may be deferred if the hernia mass reduces with gentle manipulation and if there is no clinical evidence of strangulated bowel. Though strangulation is usually clinically evident, gangrenous tissue can occasionally be reduced into the abdomen by manual or spontaneous reduction. It is therefore safest to repair the reduced hernia at the earliest opportunity. At surgery, one must decide whether to explore the abdomen to make certain that the intestine is viable. If the patient has leukocytosis or clinical signs of peritonitis or if the hernia sac contains dark or bloody fluid, the abdomen should be explored.

Durable repair requires that any correctable aggravating factors be identified and treated (chronic cough, prostatic obstruction, colonic tumor, ascites, etc) and that the defect be reconstructed without tension.

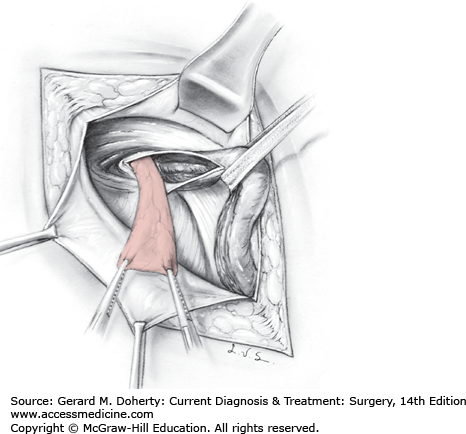

An indirect hernia sac should be anatomically isolated, dissected to its origin from the peritoneum, and ligated (Figure 32–2). In infants and young adults in whom the inguinal anatomy is normal, repair can usually be limited to high ligation, removal of the sac, and reduction of the internal ring to an appropriate size. For most adult hernias, the inguinal floor should also be reconstructed. The internal ring should be reduced to a size just adequate to allow egress of the cord structures. In women, the internal ring can be totally closed to prevent recurrence through that site.

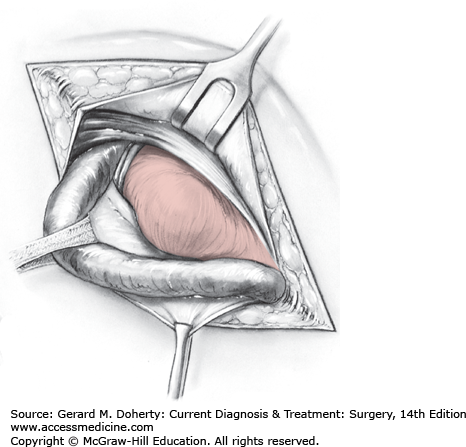

In direct inguinal hernia (Figure 32–3), the inguinal floor is usually so weak that a primary repair using the patient’s own tissues would be under tension. Although a vertical relaxing incision in the anterior rectus abdominis sheath was traditionally used, most hernia repairs are now performed using mesh so that a tension-free repair can be accomplished.

Even though a direct hernia is found, the cord should always be carefully searched for a possible indirect hernia as well.

In patients with large hernias, bilateral repair has traditionally been discouraged under the assumption that greater tension on the repair would result and therefore would increase the recurrence rate and surgical complications. If open mesh repair or laparoscopic methods are used, however, bilateral repairs can be done with low risk of recurrence. In children and young adults with small hernias, bilateral hernia repair is usually recommended because it spares the patient a second anesthetic.

Recurrent hernia within a few months or a year of operation usually indicates an inadequate repair, such as overlooking an indirect sac, missing a femoral hernia, or failing to repair the fascial defect securely. Any repair completed under tension is subject to early recurrence. Recurrences 2 or more years after repair are more likely to be caused by progressive weakening of the patient’s fascia. Repeated recurrence after careful repair by an experienced surgeon suggests a defect in collagen synthesis. Because the fascial defect is often small, firm, and unyielding, recurrent hernias are much more likely than unoperated inguinal hernias to develop incarceration or strangulation, and they should nearly always be repaired again.

If recurrence is due to an overlooked indirect sac, the posterior wall is often solid and removal of the sac may be all that is required. Occasionally, a recurrence is discovered to consist of a small, sharply circumscribed defect in the previous hernioplasty, in which case closure of the defect suffices.

The goal of all hernia repairs is to reduce the contents of the hernia into the abdomen and to close the fascial defect in the inguinal floor. Traditional repairs approximated native tissues using permanent sutures. More recently, synthetic mesh has supplanted tissue repairs because multiple prospective, randomized studies have shown lower recurrence with tension-free mesh repairs than traditional primary tissue repair.

Over the past 20 years, increased experience has been gained with minimally invasive techniques for hernia repair. Laparoscopic approaches offer less pain and more rapid return to work or normal activities. Multiple randomized trials have compared open and laparoscopic hernia repairs. Although details of specific studies vary, long-term recurrence rates of open and laparoscopic repairs are similar. The success of laparoscopic approaches is dependent on experience of the surgeon, as is also true for open repair.

Although repairs today overwhelmingly employ prosthetic material, the presence of infection or need to resect gangrenous bowel may make use of nonbiologic mesh unwise. In these situations, primary tissue repairs may still be a preferable option. For this reason, surgeons need to know the traditional techniques even though they are rarely used today.

Among the traditional autologous tissue repairs, the Bassini repair is the most widely used method. In this repair, the conjoined tendon is approximated to the Poupart ligament, and the spermatic cord remains in its normal anatomic position under the external oblique aponeurosis. The Halsted repair places the external oblique beneath the cord but otherwise resembles the Bassini repair. Cooper ligament (Lotheissen–McVay) repair brings the conjoined tendon farther posteriorly and inferiorly to the Cooper ligament. Unlike the Bassini and Halsted methods, McVay repair is effective for femoral hernia but always requires a relaxing incision to relieve tension. Recurrence rates after these open nonmesh repairs vary widely according to skill and experience of the surgeon but population studies show them to range from as low as 5%-10% to as high as 33%. Though the Shouldice repair has a lower reported recurrence rate, it is not widely used, perhaps because of the more extensive dissection required and a belief that the skill of the surgeons may be as important as the method itself. In the Shouldice repair, the transversalis fascia is first divided and then imbricated to the Poupart ligament. Finally, the conjoined tendon and internal oblique muscle are also approximated in layers to the inguinal ligament.

The open preperitoneal approach exposes the groin from between the transversalis fascia and peritoneum via a lower abdominal incision to effect closure of the fascial defect. Because it requires more initial dissection and is associated with higher morbidity and recurrence rates in less experienced hands, it has not been widely used. For recurrent or large bilateral hernias, a preperitoneal approach using a large piece of mesh to span all areas of potential herniation has been described by Stoppa.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree