The approach of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is significantly different from that of modern orthodox medicine. Without the modern technology that has allowed isolation of pathogens and pathologies, it developed strategies for understanding and correcting an illness from the broader experience of its impact and associations. There was less opportunity to focus on or directly treat a specific disease entity. Rather, traditional medicine sought to avert adverse influences and to promote normal healthy function so as to help the person eliminate or resist these influences. It was more an interaction with the body’s functions than, as in the modern case, with pathologies (that are usually the end-result of dysfunctions).

The underlying principles of Chinese medicine often appear to the Western observer to be wrapped in vague or mystical notions. However, such prejudices arise from the nineteenth-century Western view of the world as clockwork mechanisms. As modern science begins to appreciate the complexities of living systems, it has rediscovered principles that may be consistent with the oriental insights.

The yin and yang concepts are obvious examples where speculative entities are seen to substitute for empirical data. This disquiet may be diminished, however, if they are instead seen as means of classifying the experience of constant change. The yang is the active aspect of any phenomenon, the dispersive, centrifugal, transforming and expansive. Such descriptors are similar to those ascribed to chaotic tendencies in complex dynamic systems. The yin is the substantive or nourishing aspect of any phenomenon, the condensing, centripetal, sustaining and preserving. The tendencies to ordered behaviour in dynamic systems have similar qualities.

In the language of complex dynamic systems, life is seen to exist at the edge of chaos, maintaining maximum adaptibility and creativity by balancing static orderliness and turbulent chaos, and avoiding extremes of either. The essential endeavour of the Chinese physician is to restore the balance of the body, the yin nourishment and yang activity. Obviously this is done in terms of clinical symptoms rather than as an abstract philosophical construct.

The yin–yang polarities are imbued with shifting temporal and spatial relationships. At any position or in any event there will always be a blend of the active and the substantial, a blend that is always shifting in time and when viewed from different perspectives. To take a simple example: in the West, a table is an object, fixed and substantial. In the Chinese view that structure is merely in a transitory substantial, yin, phase: it also forms a relationship with the people who use it and has an influence on the room in which it stands. Moreover, these active, yang, aspects of its existence determine when its yin aspect changed from being a tree, and when it changes again to a heap of ash or a children’s playhouse! Thus, each table becomes a different entity to each individual human being and at each moment in time, its active aspect always reflecting the position of its substantial and vice versa: it becomes an experience.

Similarly, any symptom of ill health might either be the mark of excessive activity (yang) in a system or alternatively relative stasis or congestion (yin). In the first case, treatment would concentrate on encouraging the nutritive, assimilative and/or calming influences in the body, mind or spirit; in the second there would need to be a degree of stimulation or mobilization. The art of diagnosis was to distinguish between the two radically different scenarios; the art of medicine to develop appropriate strategies for the particular system defect.

Other polarities would be taken into account (heat versus cold, internal origins versus external, deficient constitutions versus the highly charged, and so on) along with a good number of other qualitative markers of the interior climate. One early view, for example, was that chronic diseases arose when external pathogenic influences drove deeper and deeper into the body. Treatment therefore required that the pathogenic influence was best intercepted at the surface, that is, at its most acute (even alarming, often febrile) stage, to prevent the development of more intractable ‘embedded’ pathologies. Treatment strategies would be quite different at each stage of penetration.

Another Chinese fundamental is the concept of an underlying energy in all phenomena, as a motive force and determining principle. They did not measure qi as calorific or electrical energy. Instead, qi is appreciated and judged by ordinary experience, and indeed for this reason is clearly felt as tangible. Qi is thus an energetic construct implicit in, and defined by, its outcomes, i.e. by events. It is therefore manifest in all movement and is itself in movement, constantly transforming itself into relatively yang and yin aspects.

In physiological terms, qi was often subdivided into fluids of different densities, some visible and some not. One of the substantial or yin aspects of qi, for example, is blood or xue. Although this was obviously the same fluid as understood anywhere else it also had other qualities. Xue can be appreciated as incorporating both what the West knows as blood and the subjective effect of that fluid, warming, pulsing and nourishing. It can also be seen as a deeper, slower, more profound or tangible response to change than other qi, a response that is, by definition, also slower to reverse. For example, it may be manifested as long-term physiological responses or the organic change that leads to observable pathologies. Incidentally, in this context herbal medicines were seen to be more effective in moving xue (the more substantial shifts in body function) than acupuncture.

The Chinese view of organ function is also quite distinct, derived from induced insights of clinical presentations and the meridianal connections applied in acupuncture. Thus, gan, the liver, has the function of distributing energies around the body, governing muscle and sinew activity and eyesight, and is particularly disturbed by emotional distress, particularly anger and frustration. The spleen, pi, is responsible for assimilative functions, notably digestion, and for maintaining the integrity of the tissues and circulation, but also includes emotional assimilation as manifested in empathy, maternalism and nurturing. (These notions of concentric repetition of patterns, so that activity at a physical level is manifested also at psychological, emotional, spiritual or even social levels now resonates with one of the mathematical principles of complex system analysis, the fractal, where a pattern is repeated through infinite levels of scale.)

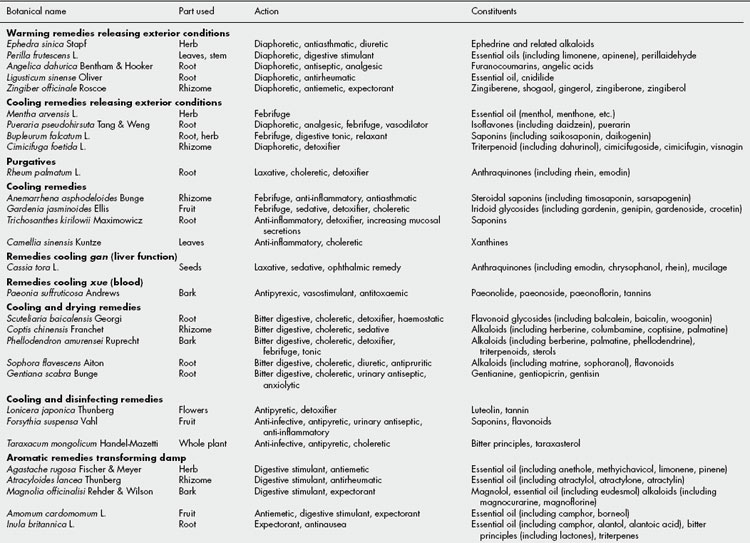

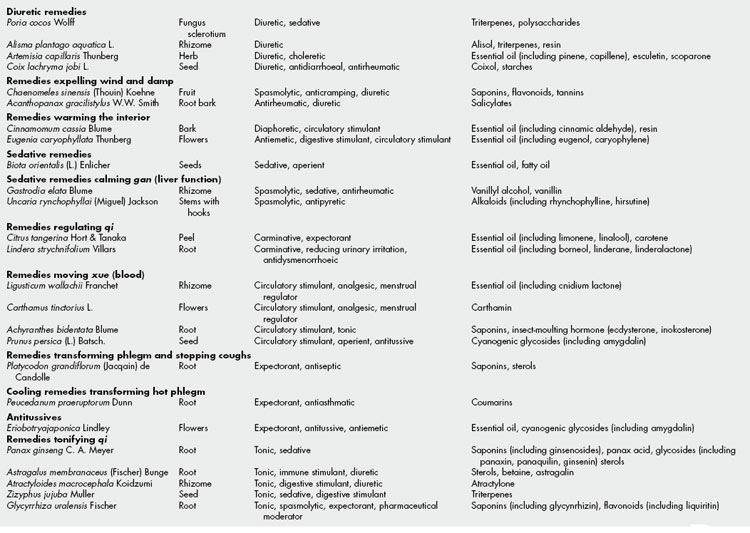

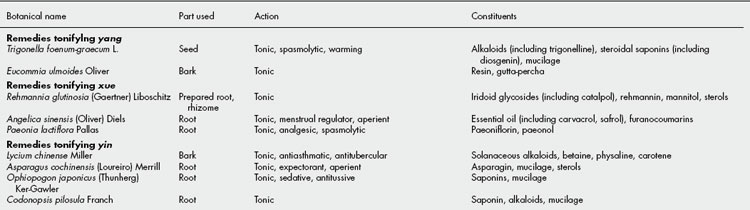

The Chinese herbs were classified according to their perceived ability to affect any of these manifestations of the living body. These classifications are used in Table 37.1, which lists some of the most widely used Chinese herbs in the West. Herbs were also characterized pharmacologically in terms of their taste: bitter, sweet, acrid, salty and sour, this being seen to denote particular properties. Some of the conclusions drawn about such properties can now be supported with modern knowledge of the action of the archetypal plant constituents involved (Mills and Bone, ‘Further reading’).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>