1 Herbal therapeutic systems

Chapter contents

From the beginning: popular practices

Plants and humans share many experiences. Humans are of course one species spread around the world with all individuals sharing essentially the same physiology and anatomy. However, even the myriad species of plants share more than they differ, with common mechanisms of primary metabolism and cell structure and many common strategies of regulation, reproduction and even defence. Although there are vast numbers of pharmacologically active ‘secondary’ metabolites in plants, they mostly classify into a small list of phytochemical groups (see Chapter 2). A review of human medical cultures shows that there are common themes that may arise from consistent experiences of consuming plants. When these themes are recast in the light of modern scientific enquiry one may glimpse therapeutic approaches that are radically different from those which underpin conventional medicine.

As it is now known that animals use plants for medicinal purposes,1,2 it is unlikely that there was a time when humans did not use herbal remedies. There is prehistoric evidence of the use of medicinals from the USA3 and medicinal plant traces found at neolithic sites.4 There are also innumerable accounts of medicinal plants being used by small communities around the world, living wholly within the natural world and crafting their survival from the facilities around them.5–7

Most of what is known about herbal use from recorded history is provided by early texts, often among the earliest of all known books. However, one overwhelming gap in this record is that, although in its original mode herbal medicine was centred in local communities and practised largely by women, this is barely reflected in contemporary accounts.8 After the demise of organised medicine with the collapse of the Roman empire, healthcare in Europe for most people was again provided at a very local level, probably including a mix of herbs and diet, together with faith and holy relics, as well as astrology, pagan incantation and ritual9 (the Inquisition permitting – millions of women were killed for practising ‘witchcraft’ across Europe from the 13th to the 18th centuries).10 Hildegarde von Bingen, one of the first prominent woman authorities in Europe, achieved particular renown through her medicinal text Physica. In it, she became the first woman publicly to discuss plants in relation to their medicinal properties.11 She was, however, a solitary exception to the prevailing view that women were not in the forefront of academic, professional or literary efforts. Like her, however, most European writers of the time were from the monastic tradition, only moving into the popular arena around Chaucer’s time. By then well-organised medicinal gardens and practices were recorded in England by authors such as Henry Daniel, John Arderne, John Bray and Chaucer himself, all reflecting on current medicinal practice across Europe in the 14th century.12 Where systems were apparent in these texts, they appear to have been derived from the Graeco-Roman tradition with varying amounts of astrology, especially in works by Culpeper and Gerard. It was only with the works of Paracelsus that scholarship began substantially to question the previous deference to Galen and medicine moved into the modern technological age, leaving folk practice way behind.

Such was the enormous variety of folk practices around the world that one must conclude that, while most rationales were based on empiricism, local shibboleths and traditions often acted as a brake on innovation. Nevertheless, there are likely to have been common features. A fascinating account of one remote group in Central America13 shows significant similarities between their and other humoral approaches around the world. It is also certain that where therapeutic systems did develop, they were based on popular practices.

Graeco-Roman and Islamic medicine

The systematic development of medical ideas that started with the Hippocratic writings from the Greek island of Kos in the fifth and fourth centuries bc and climaxed in the work of Galen in the second century ad, laid the foundations for European medicine until the scientific era, and the framework for Islamic medicine until the present time. They were marked by almost modern standards of empiricism, logic and rigour.14

The Hippocratic writings,15 a complex series of treatises from a school rather than from one individual, were an astonishing event. In passages of renaissant illumination, they evidenced an enlightened tradition that invoked dietary, lifestyle, environmental and psychotherapeutic means to encouraging health. The Hippocratic tradition is generally associated with the concept of the natural healing power of life, the vis medicatrix naturae. In fact, most of the texts are pragmatic guides to maintaining health and to the practice of medicine, with some passages (e.g. The Art of Medicine) being undisguised paeans to the importance of physicians in healthcare!

There were herbs included in the Hippocratic canon, but it was a wider doctrine of whole healthcare that was being formulated. It was left to others to formulate the materia medicae of the day. The Greek Dioscorides in the first century ad rigorously collected information about 500 plants and remedies in tours with the Roman armies and collated them in his seminal Materia Medica.16

1. The drug must be of good unadulterated quality.

2. The illness must be simple, not complex.

3. The illness must be appropriate to the action of the drug.

4. The drug must be more powerful than the illness.

5. One should make careful note of the course of illness and treatment.

6. One must ensure that the effect of the drug is the same for everybody at every time.

7. One must see that the effect of the drug is specific for human beings (in an animal it can have another effect).

8. One must distinguish the effect of drugs (working by their qualities) from foods (working by their substance).

In further passages (most have never been translated into English) he shows clear evidence of modern logical thought in setting out a series of experiments to prove that the kidneys were the source of urine into the bladder.14

All medicines considered in themselves are either hot, cold, moist, dry or temperate.

Such as are hot in the second degree, as much exceed the first, as our natural heat exceeds a temperature. Their use is to open the pores, and take away obstructions, by relaxing tough humours and by their essential force and strength, when nature cannot do it.

Cooling remedies are inherently more risky. The ultimate cold is the corpse. Nevertheless, they can be used to contain excessive vital responses such as pain, ‘choler’ and excessive eliminations (‘defluctions’). Intriguingly, at the gentlest such level, the effect is to ‘cause digestion’; the bitters (see p. 84) were included in this category, the attraction being that these cooled but did not depress, reducing heat by switching the physiology towards increased digestive activity (universally seen as cooling) and thus increased nourishment, a highly attractive tactic in many fevers. Also intriguing is the insight at the other end of the spectrum. Using powerful sedatives when all else fails and death is imminent (‘in extreme watchings’) is one of the less formally advisable clinical knacks from a more desperate age; it appears that the effect can be to wipe out the clamour of adversity at that stage of crisis so that new life might just flicker back. The works of the Graeco-Roman writers were most extensively remodelled by the medical writers of the Islamic era. Up to 100 authors on pharmaceutics and materia medica are identifiable in the Arabic bibliographies, most copying and adapting directly from Dioscorides and Galen. There were, however, notable developments, including the work of the Persians al-Majusi (Ali Abbas), ar-Rhazi (Rhazes) and Ibn-Sina (Avicenna), the Jew Maimonides and the Christian Hunayn ibn-Ishaq. However, not for the first time in reviews of classic texts (the Chinese canon is another example) there is a sense that much that was written was truly theoretical, with evidence of systematisation by rote, showing little regard for likely actual practices.17

Nevertheless, it is apparent that in Islamic pharmaceutics considerable respect was paid to the qualities of individual herbs (unlike the Chinese emphasis on formulations, these were seen as reflecting a secondary skill). Physicians were expected to understand intimately the nature of each remedy, its natural habitat, its specific energy pattern, actions, indications, specific relationships to the organs, duration of action, toxicity and contraindications, types of preparation, dosage, administration and antidotes.18

The Islamic medical tradition as Unani/Tibb has been maintained in its heartland until the present day and it also generated important benefits for the medicine of Europe. Montpellier and Salerno were among the first of the new medical centres of Europe. Rather than relying just on ancient texts, a new experimental culture led to reports of the tested effects of substances from identified plants. This advance was fostered by the foundation of universities and greatly aided by the later invention of the printing press, which also allowed wider dissemination of the classical texts.19

Chinese herbal medicine

This text is not the place for an exhaustive overview of Chinese medicine. There are effective texts available in English, notably the essential work by Unschuld,20 other classic texts,21,22 one very accessible introduction,23 a rigorous yet practical review,24 and a summary designed to help the Western practitioner.25 What will be attempted here is the distillation of uniquely herbal strategies and concepts from the vast corpus of Chinese medicine. There is much to choose from. Over the last 2000 years a number of seminal texts and systems have been developed, each incorporating the developments of their predecessors. These were often very intricate systems, reflecting perhaps the priorities of scholarship and portent lore (much theorising at the early stages was for the Imperial court26). At more than one stage, there appears to have been some difficulty in organising the empirical folk traditions into neat systems20 and there is always a suspicion that realities may have been squeezed to justify the cosmology.

However, Chinese medicine was certainly not idle theorising. In one review of the medicine of early China,27 it has been pointed out that among other ‘modern’ advances were the use of androgens and oestrogens (in placentas) to treat hypogonadism, the development of forensic medicine, the advocacy of hand washing to avoid infection and the association of hardening of the arteries with high salt intake. Qualifying examinations for physicians were conducted by the Chinese state as early as the first century ad and there was an elaborate system of medical ethics.

It is first important to emphasise that the Chinese world view has been fundamentally different from that in the West since the time of Aristotle. In Chinese thinking everything moves (the seminal classic, the I Ching, is translated as the ‘Book of Changes’). Events are automatically described by their transient qualities in relation to other events and are manifestations of energies in ways that the West understood only after Einstein.28 The generic term for these energies is qi, but in the case of the living body there are many forms of varying density, from wei qi as the most rarefied on the body surface, manifest in acute defensive reactions like fever and colds, through ying qi, the nourishing qi flowing through the meridians, to xue or blood, the most substantial aspect of qi, manifest in many somatic events. Qi is also manifest in jing (essence) and the body fluids. The comparison with modern physics is even more apposite as qi is simultaneously energy, movement and fluid (reminiscent of attempts to define light as waves and/or particles).

Each pair denotes a spectrum of qualities onto which any illness can be placed; each implies that the aim of any therapeutic measure is to move extremes back towards a healthy mean. Although used as a diagnostic framework for acupuncture, it is widely agreed that TCM is primarily based on herbal therapeutics. Thus herbs are ascribed temperaments or tendencies accordingly: they may be Yin or Yang, tonic or dispersive, cooling or heating, eliminative or constructive. These manifestations are in turn aspects of fundamental properties of the remedies (see Table 1.1).

| Condition | Attributes |

|---|---|

| Yang | Active, expanding, transforming, dispersive, centrifugal, aggressive, light |

| Yin | Constructive, sustaining, completing, condensing, centripetal, responsive, dark |

| Full | Repleted |

| Empty | Depleted |

| Hot | Active |

| Cold | Passive |

| External | Acute |

| Internal | Chronic |

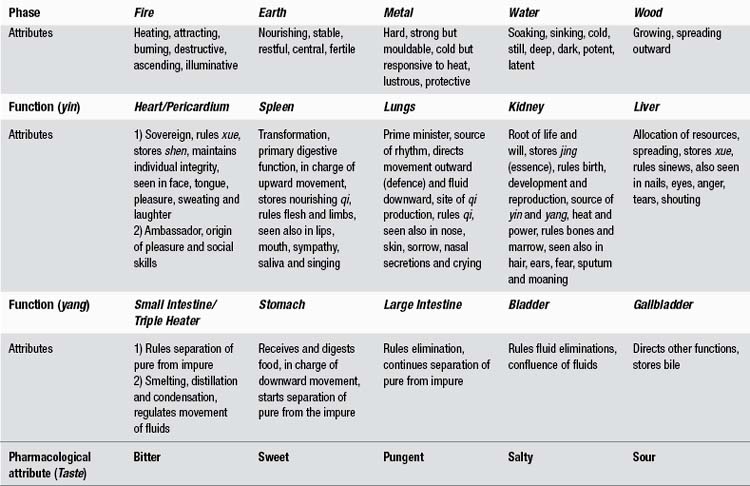

In Chinese medicine there is little regard for anatomy and the main entities upon which pathogenic or therapeutic forces act are essentially functional and physiological. There are six pairs of functions, often confusingly translated in the West as ‘organs’. These, like all phenomena in the Chinese world, are ascribed to points on the five-phase cycle that further illuminate their qualities. The five phases (the frequently used term ‘five elements’ is clearly not appropriate here) are seasonal and cyclical transitions through which all the universe moves. They have a multitude of dynamic relationships with each other and an array of more or less consistent qualities. The five phases, their attributes and their relationship with the six pairs of functions are illustrated in Table 1.2.

Following the strictures of Porkert,21 words in this text which may be confused with their Western meanings are distinguished typographically (with capitals and italics though not, as he insisted, using completely new words altogether).

The five Tastes (Chinese pharmacology)

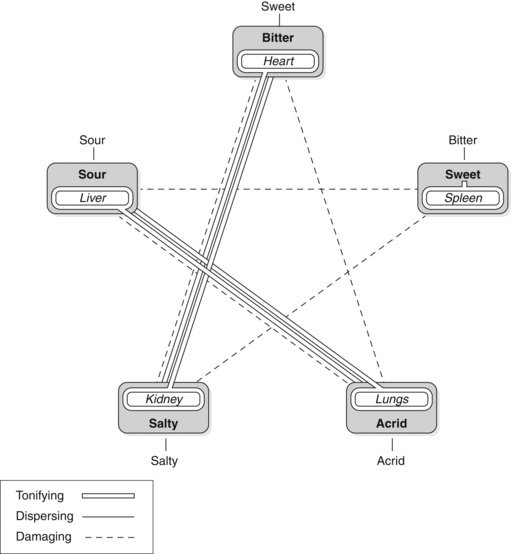

While a moderate amount of each Taste is necessary for its corresponding Function, there are also wider effects arising from their consumption. The relationships are expressed in Figure 1.1. (For a review of the implications of the four-phase nature of the relationships and the peculiar position of the Spleen, see Mills.25)

Salty

The taste of common salt and seafood, but is not well represented in the herbal materia medica. However, seaweeds are occasionally used in maritime cultures and in Japan. It is possible to classify the occasional remedy like celery seed in this category. In China, however, the main group of drugs classified as salty are animal tissues and the minerals.

Bitter

It disperses excess in the Spleen. A modern manifestation of such a condition is the excessive consumption of sweet foods with the consequent possible disruptions in blood sugar levels. There is clinical experience of the benefits of bitter herbs in stabilising such disruptions.

In excess it damages the Lungs. Excessive cooling suppresses vital defences.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree