Hemorrhoid Management

Andreas M. Kaiser

Hemorrhoids are a pathologic engorgement of the hemorrhoidal plexus. The latter are part of the normal anatomy of the anal canal and form soft cushions that contribute to fine-tuning the anal seal. Hemorrhoids are classified as internal (if they occur above the dentate line), external (if found below), or mixed (if both).

The true etiology of hemorrhoids remains a matter of speculation: Apart from an individual/familial predisposition, they have been associated with the Western culture and diet, constipation with straining, and pregnancy with impaired venous return. In contrast to common opinion, liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension are not associated with a higher incidence of hemorrhoids, but can result in rectal varices (typically located in mid to upper rectum).

Hemorrhoid symptoms are nonspecific in nature. Internal hemorrhoids can cause bleeding and, with increasing size, tend to prolapse. Hemorrhoids do not itch, but a prolapse may result in chronic moisture which then triggers an itching sensation. External hemorrhoids are most commonly asymptomatic (innocent bystanders); occasionally, they cause difficulty with the local hygiene (if very large), or they may develop an acute painful thrombosis. Pain otherwise is rare and only occurs in nonreducible, potentially gangrenous prolapsed hemorrhoids. Complaints of recurring/persistent pain and “painful hemorrhoids” should therefore direct the examination to look for a fissure with a sentinel skin tag. Be careful to exclude other pathology before ascribing rectal bleeding to “hemorrhoids.”

SCORE™, the Surgical Council on Resident Education, classified hemorrhoidectomy and banding for internal hemorrhoids as “ESSENTIAL COMMON” procedures. SCORE™ classified stapled hemorrhoidectomy as a “COMPLEX” procedure.

STEPS IN PROCEDURES

Excisional Hemorrhoidectomy (Internal and External Hemorrhoids)

Prone jackknife or lithotomy position

Avoid unnecessary anal dilation

Place retractor, inspect the three hemorrhoidal pedicles, and identify the number of hemorrhoidectomies to be carried out (generally 1–3)

Place one Kelly clamp on the first target pedicle and pull outward, place second Kelly clamp on inner aspect of pedicle thus exposed

Place absorbable suture ligature at apex of hemorrhoidal pedicle

Make a V-shaped incision to the external skin and extend it to a narrow eye-shaped mucocutaneous incision toward the ligated vascular pedicle

Lift the external angle of the “eye” and dissect it off the underlying external and internal sphincter structures (transverse fibers), using blunt dissection, sharp scissors, electrocautery, or more expensive but not more effective energy devices/lasers

Once the ligated pedicle is reached, amputate the hemorrhoid (send for pathology)

Bury the ligated stump, and close the mucocutaneous defect (Ferguson technique) with running absorbable sutures, leaving only the most external portion open. Alternatively, the wound may be left open (Milligan–Morgan technique)

Repeat for up to two more pedicles, making sure that sufficient epithelial bridge is preserved between the excision sites

HALLMARK COMPLICATIONS

Bleeding

Urinary retention

Recurrence

Sphincter injury and dysfunction

Pelvic sepsis

Stricture

LIST OF ANATOMIC STRUCTURES

Inspection/palpation landmarks:

Perineum

Anterior or urogenital triangle

Posterior or anal triangle

Symphysis pubis

Ischial tuberosities

Coccyx

Anus, anal verge, four perianal quadrants (left/right, anterior/posterior)

Dentate line (pectinate line):

Anal crypts

Anal columns (of Morgagni)

Blood supply:

Internal iliac arteries

Inferior rectal (hemorrhoidal) arteries

Inferior mesenteric vein

Superior rectal (hemorrhoidal) vein

Internal iliac vein

Middle rectal (hemorrhoidal) vein

Rectal (hemorrhoidal) plexus of veins

Muscular structures:

Internal anal sphincter (smooth muscle, white)

External anal sphincter (skeletal muscle, red)

Intersphincteric groove

Puborectalis muscle (skeletal muscle)

Evaluation and Decision Making

Modern management of hemorrhoids depends on the acuity of presentation, the degree, type and evolution of symptoms, and the clinical findings. Under elective circumstances, conservative measures should be initiated, and additional interventions tailored to the specific needs.

Internal hemorrhoids are classified on a largely patient-reported scale from I–IV. Grade I hemorrhoids are enlarged cushions and may bleed but do not prolapse through the anal canal. Grade II hemorrhoids protrude during straining, but spontaneously reduce on relaxation. Grade III hemorrhoids protrude and require manual reduction, which is usually easily accomplished. Grade IV hemorrhoids are irreducible protrusions of internal (mucosa-covered) hemorrhoids. The most frequent confusions include incorrect interpretation of a large external (skin-covered) hemorrhoid component with any internal degree as grade IV, or confusion of a true rectal prolapse with prolapsing hemorrhoids. Note that a true mucosal rectal prolapse will show concentric folds of mucosa, and prolapsing hemorrhoids present with a radial pattern of mucosal protrusions.

If previously grade II or III internal hemorrhoids do not reduce quickly enough, edema rapidly occurs because the anal sphincter acts as a tourniquet. Increasing swelling and pain prevent reduction, and a vicious circle starts which may lead to tissue gangrene. This acute prolapse (grade IV) is typically very painful and therefore an emergency. Rarely, grade IV hemorrhoids are chronically prolapsing and not painful, often in the context of a lax anal sphincter that is unable to retain the hemorrhoids in a reduced position and does not strangulate the prolapsed tissue.

An excisional hemorrhoidectomy, typically performed under general or spinal anesthesia, is still the gold standard but it is generally more painful than the alternatives. It is the standard approach for (A) emergency situations (grade IV incarcerated internal hemorrhoids with/without gangrene), or (B) electively for large, mixed internal and external hemorrhoids (grades I–III) if the patient desires a removal of the external component as well. If a patient is only symptomatic from the internal hemorrhoids and not annoyed by any degree of external component, treatment should focus on the internal hemorrhoids only. In addition to conservative measures, an office procedure (banding, sclerosing, infrared coagulation) is simple, well tolerated, avoids anesthesia, and might provide adequate relief after a single or repeated applications. Cryotherapy for hemorrhoids is considered obsolete. However, a stapled hemorrhoidectomy (aka hemorrhoidopexy), performed under general or spinal anesthesia, is an excellent solution for very voluminous internal hemorrhoids (grades II/III, occasionally grade I) or if office procedures have failed.

Age- and risk-adjusted colon evaluation is mandatory before all elective hemorrhoid interventions.

In this chapter, classic excisional hemorrhoidectomy, stapled hemorrhoidectomy, and rubber band ligation are described. The references at the end list a number of systematic reviews and reference texts.

Excisional Hemorrhoidectomy

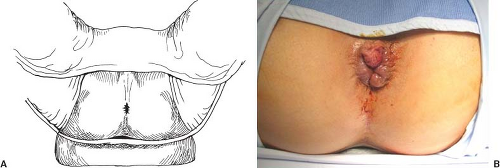

Patient Positioning and Setup (Fig. 122.1)

Technical Points

The procedure may be performed in the prone jackknife or lithotomy position—a debate that largely remains a matter of personal preference. The prone jackknife position is more convenient for the surgeons and reduces the venous congestion in the hemorrhoids. The lithotomy position is preferred by some because it is quickly set up (Fig. 122.1A) and provides better control of the airway. In high-risk patients (e.g., super-obesity, ankylosing spondylitis), the lithotomy position may be

somewhat safer. Addition of local anesthesia helps with sphincter relaxation and postoperative pain control.

somewhat safer. Addition of local anesthesia helps with sphincter relaxation and postoperative pain control.

After adequate anesthesia has been induced, the anus is again carefully examined and a digital examination performed (Fig. 122.1B). However, the historically recommended finger dilation should be avoided as it may cause damage to the sphincter complex. Use of povidone–iodine solution (Betadine) for lubrication rather than water-soluble lubricant keeps the operative field less slippery during the procedure.

Anatomic Points

The perineum is a diamond-shaped region bounded by the pubic symphysis anteriorly, the coccyx posteriorly, and the two ischial tuberosities laterally. A transverse line connecting the anterior edge of the ischial tuberosities and passing just anterior to the anus divides the region into two triangles: An anterior urogenital triangle and a posterior anal triangle. The detailed anatomy of the perineum is discussed in Chapter 101 and hence is only briefly be reviewed here. The posterior triangle contains the anus and associated musculature as well as neurovascular structures. Specific locations around the anus are best described by assigning them to one of four quadrants (left/right, anterior/posterior), whereas the clock as orientation is confusing if the patient’s position changes.

The anus links the terminal part of the gastrointestinal tract (endodermal origin) with the outside (ectodermal origin). The dentate line or pectinate line represents this important embryologic and anatomical landmark where epithelium, vascular, lymphatic, and neural anatomy switch from visceral to somatic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree