10 Helping a person go Smoke Free

a reflective approach

INTRODUCTION

Integrative hypnotherapy incorporates complementary therapies to create an individualized and client-led approach to smoking cessation. Hypnotherapy alone has been reported to assist people to feel engaged and empowered in the process of smoking cessation (Ahijevych 2000). A review of the non-pharmacological research literature suggests that smoking cessation can be helped through a structured programme of support from health professionals (Lancaster et al 2000), which can also be assisted by the use of auricular acupuncture (White et al 2000) (Fig. 10.1A). Massage and reflexology (Fig. 10.1B) have also been claimed to support patients in managing cravings in combination with standard nicotine replacement therapies (Hernandez-Reif et al 1999, Maycock & Mackereth 2009). In a clinical environment, this heady mix of interventions may confound some practitioners used to a mono-therapy approach. Inevitably, critics demand evidence for each element of such a complex package and integrative hypnotherapy provides scope for quality research endeavours. World tobacco control initiatives include protecting people from passive smoking, offering support to people who want to stop smoking and warning and informing people about the dangers of tobacco (Bala et al 2008). The challenge is how these objectives can be achieved in a therapy room. It is hoped that the reflective practices (which help unfold each element of the SEEDING model) and the real case studies that demonstrate an integrative approach will help therapists cultivate qualities, such as flexibility, empathy and curiosity, in order to help them assist their clients to become ‘smoke free’.

THE SEEDING MODEL

Jay Haley first introduced the concept of ‘seeding’ in Uncommon Therapy (1973), based on his analysis of the work of Milton H. Erickson. Haley noted that Erickson would seed or establish ideas and refer back to them several times during a session or series of sessions to create a specific response-set (conditioned behavioural responses) that could evoke a powerful and appropriate response to a given suggestion. Seeding is not unique to hypnotherapy, it is also known as ‘priming’ when employed by social psychologists or ‘foreshadowing’ when used as a plot device in literature or films (Zeig 1990).

The SEEDING model, as illustrated below, is more than a handy acronym to remember effective and powerful elements of integrative hypnotherapy. Seeding can take place at many levels during a hypnotherapy session and can also be used as a pre-hypnotic technique that requires strategy or a therapeutic ‘planning ahead’ and starts from the moment of contact with your client. Geary (1994) suggests that seeding can also occur on multiple levels with pauses, tonality, volume, inflection, gestures, word-play and even postural changes. The macro and micro applications are limited only by the ability and imagination of the therapist.

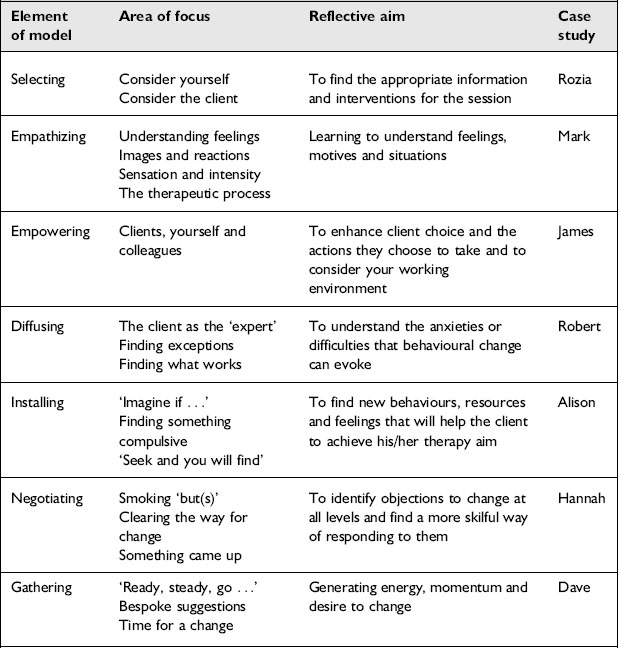

The SEEDING model presented in Box 10.1 creates a menu of therapeutic interventions that can be used selectively (as each can evoke or ‘seed’ a useful response-set) or in a synergistic combination where each seed will reinforce the other. There will inevitably be some overlap between elements but this also provides opportunities for consolidation and review. You may feel that some of the reflective practice exercises could be more appropriately used within a different element of the model. Feel free to customize and use as creatively as you wish. At the end of this chapter, you may like to think how to ‘grow’ the model for your own practice.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

Reflective practice, as defined by Schön (1983), involves carefully considering real world experiences and linking knowledge to practice. This is a continuous process of reviewing professional practice, which can be facilitated, supported or coached through supervisory, mentoring or preceptorship arrangements (Morton-Cooper & Palmer 2000). Models of reflective practice have been developed to guide practitioners in the process. These can include frameworks and/or cyclical processes (Gibbs 1988, Johns 2004), which ask questions, such as: ‘What happened?’, ‘How might you respond differently next time?’, ‘What are the ethical and/or professional issues raised by the situation?’. The goal of any model is not to be prescriptive, rather to enable the professional to grow their practice. Using the SEEDING model we have devised a series of questions (these are not exhaustive) for therapists to use ‘in’ and ‘reflect on’ smoking cessation practice. The model, case study examples and reflective practice points are summarized in Table 10.1.

This model is not an attempt to itemize reflective practice, force interventions into arbitrary stages or be rigidly adhered to. You may feel that some of the reflective practice exercises could be more appropriately used within a different element of the model – feel free to customize and use as creatively as you wish. As Johns (2002: 17) suggests, a model can help the therapist to bring together ‘fragments of experience into a meaningful whole’.

1 SELECTING: APPROPRIATE INFORMATION AND INTERVENTIONS

In reality, smoking cessation leaflets may be unwelcomed or not given at the right time, with the result that they are put aside without being read. This is despite local and national printed smoking cessation materials being highly accessible, multi-lingual and quality controlled, with useful contact details and advice on the safe use of pharmacological and non-pharmacological products. They can also act as an aide memoire or positive reinforcement to the client’s desire to stop smoking. For smokers who have high health literacy, or would prefer to work privately and in their own way, this could be the information and intervention of choice. A good knowledge of the contents of any smoking cessation material provided can help the therapist to ‘tailor’ information or refer to specific parts that could interest or motivate. This tailoring sends a powerful message to the client that their needs are being listened to carefully. For those smokers taking the first tentative steps towards becoming smoke-free and ‘checking out’ the service, the offer of a booklet with a warm smile (even on the telephone you can tell when someone smiles) can anchor (a stimulus linked to a specific feeling or behavioural response) positive associations. It is important, professionally, for all therapists working in smoking cessation to have an understanding of conventional approaches, and be aware of developments in pharmacological treatments. National smoking cessation reports and guidelines are available, with research reviews and recommendations for smoking cessation practice, available online (see Further Reading and Resources).

Reflective practice 1

This practice is designed to engage the therapist in a process of identifying what information/help might be needed to make a change in an individual’s health behaviours. The therapist is then invited to consider how a client might undertake a similar process (see Boxes 10.2 and 10.3).

2 EMPATHIZING: UNDERSTANDING FEELINGS, MOTIVES AND SITUATIONS

National stop smoking campaigns ensure that smoking remains highly visible as a political, social and ecological issue. They also promote social change by affecting social norms and values about smoking (Wellings et al 2000). For many smokers, the issue of ‘social smoking’ can be more to do with shame, isolation and conflict. How smokers perceive themselves can result in ‘negative affect’ (negative emotions such as anxiety, guilt and depression) and a lack of ‘self-efficacy’, resulting in feeling unable to achieve goals. This requires a skilful and delicate touch from the therapist, as these issues, if not addressed, can undermine the therapy process and your client’s perceived ability to achieve a smoke-free lifestyle. Consider for example the much used phrase ‘willpower’. This nebulous and unhelpful term and the supposed ‘lack of willpower’ is often used in judgement by others against smokers during their stopping process and can even become part of a client’s own negative self-talk. It is also disempowering. Human beings stop smoking, not the ‘willpower’.

Reflective practice 2

This practice is designed to sensitize you (as therapist) to some of the social issues facing smokers. It will also help you and your clients to explore the construction of internal dialogues, images and sensations (see Boxes 10.4 and 10.5).